The budget debate is well under way in Frankfort, but the discussion is clouded by confusion and misinformation about the types of resources available and the consequences of taking advantage of them.

Kentucky’s fiscal situation is such that there is money available now for both important one-time expenses, such as new water and sewer infrastructure, school building construction and housing, along with critical recurring expenses, like teacher raises, full funding of student transportation and expanded child care subsidies.

But some have inaccurately suggested the state can only afford to spend additional money on certain one-time expenses. Doing so would mean a budget that fails to truly deliver for Kentuckians and that piles up billions more dollars in excessive idle funds. And given the state’s tax cutting formula, it could instead pave the way for recurring and expensive income tax cuts that put even existing budgetary investments at risk.

There are substantial recurring monies available, not just one-time

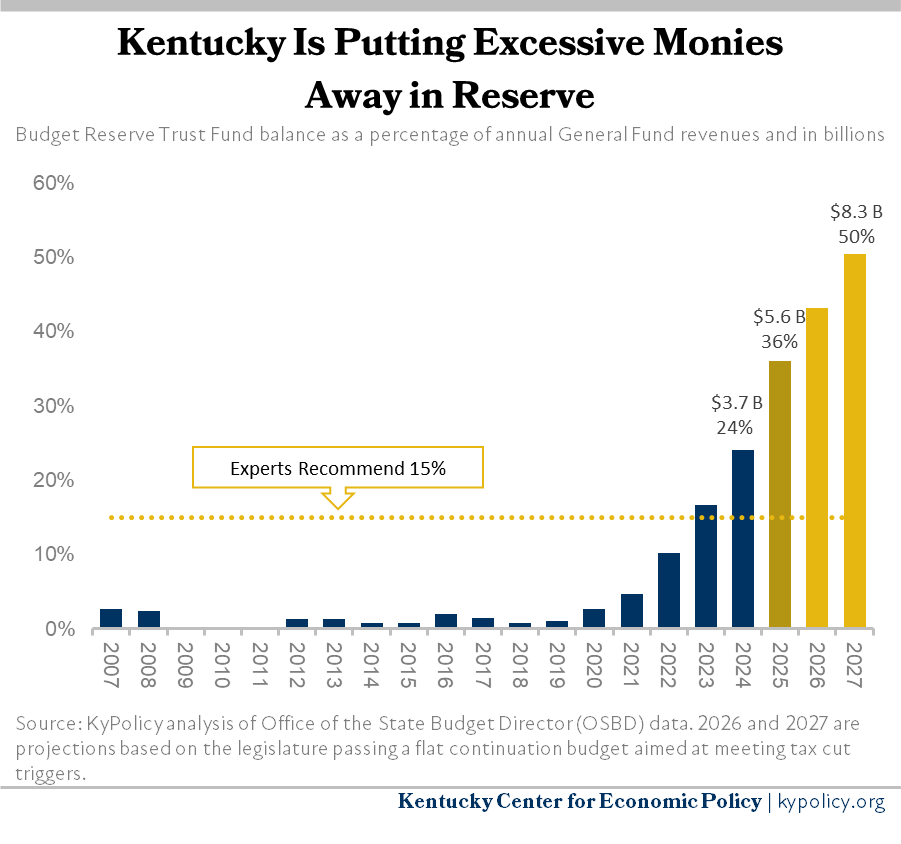

The state has built up a $3.7 billion balance in its Budget Reserve Trust Fund (BRTF), commonly called the rainy day fund. That is the result of lawmakers keeping spending far below recurring revenue every year since 2021, when a strong national economy and higher inflation increased tax receipts. Greater receipts made putting more money into the budget possible. But instead, as shown in the graph below, the state is is bringing in over $1 billion more annually than it is spending.

The Office of the State Budget Director is now estimating that the end-of-year surplus for 2024 will reach $1.9 billion – making for the fourth year in a row during which the legislature appropriated far less than the revenues available. These unspent revenues are recurring; they don’t become one-time money until they are deposited in the BRTF. This year’s surplus could make the BRTF balance climb to over $5 billion by the summer, as shown in the graph below.

Even though revenues are projected to be basically flat over the next two years, with growth of 0% in fiscal year 2025 and 2.9% in 2026, the over $1 billion the General Assembly has failed to appropriate over the past four years will continue each year as recurring revenues. That means money is available in the next budget for both one-time and ongoing expenses. One-time expenses would draw from what is already accumulated in the BRTF, while recurring expenses could be paid for with the revenue coming in that would otherwise be added to the already-overfunded BRTF.

A disastrous reduction of the income tax rate to as low as 2.5% could be at stake in this budget

And if these monies aren’t directed at recurring budget needs, they may end up going to recurring tax cuts instead. The legislature’s statutory tax-cutting formula requires that two triggers be met. The first trigger – requiring that the balance of BRTF is at least 10% of annual General Fund revenues – has already been surpassed with a current balance of 24%, as shown below. This trigger will continue to be met for the near future, even with some expenditures out of the BRTF, unless the legislature spends down a significant portion of the fund’s balance.

The second trigger requires that revenues exceed spending plus the cost of a 1% cut in the income tax rate. That cost is more than $1 billion ($1.36 billion this year) and is approximately equal to the amount that revenues have exceeded spending in recent budget years, as described above.

Based on current 2024 appropriations, it looks possible or even likely that the triggers will be met for this year, but we’ll know for sure in September. If they are met, the 2025 General Assembly will decide whether to further reduce the income tax rate from 4% to 3.5% to take effect Jan. 1, 2026. That decision will begin reducing revenue in the second year of the new budget, with the full effect to come the following year.

The question for the budget under consideration this legislative session is whether the General Assembly will continue underspending relative to revenues by over $1 billion a year in fiscal years 2025 and 2026 in order to trigger additional income tax cuts. Given that revenues are roughly flat, that would prevent new investments that aren’t mostly offset with budget cuts somewhere else. And it would make the BRTF swell even further over the biennium. Because those unspent revenues have to go somewhere, budgeting for more triggered tax cuts would make the BRTF balance reach approximately $8 billion or 50% of annual revenues by the end of the biennium, as shown below.

If the triggers are met for 2025, the 2026 General Assembly will decide whether to further lower the rate from 3.5% to 3% (assuming this year’s triggers are met and a cut is enacted) to take effect Jan. 1, 2027. And then if the triggers are met for fiscal year 2026 (the second year of the budget that will be enacted this session), an additional reduction in the income tax rate from 3% to 2.5% to take effect Jan. 1, 2028 would be on the table for the 2027 General Assembly.

These delays in when the tax cuts go into effect under the formula mean their full impact won’t be felt in the upcoming two-year budget period. But the bottom line is that the budget currently being considered in Frankfort will help determine whether the legislature is headed toward cutting the income tax rate from 5% as recently as 2022 to as low as 2.5% by 2028.

Given that income tax receipts were 41% of state General Fund revenue in 2022, and that a cut from 5% to 2.5% means slashing the income tax in half, reductions in total General Fund revenue of around 20% could be at stake. That’s more than $3 billion today, or about what is spent on the entire SEEK funding formula for public schools. In comparison, the disastrous Kansas tax cuts reduced revenue in that state by only 11%, and were rolled back five years later.

Let’s hope that more damaging tax cuts aren’t being seriously considered. The future for Kentucky’s schools, health, infrastructure and communities are on the line in decisions being made now in Frankfort.