The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps, played a key role in helping cushion Kentucky’s economy from the depths of the Great Recession. It continues to be a critical lifeline and economic stimulus for people and parts of the state facing ongoing economic challenges.

SNAP is designed to automatically help boost the economy when it falters. More people become eligible for the program when jobs are lost and incomes decline. That feature both supports families during hard times and counteracts the economic drag of lower spending.

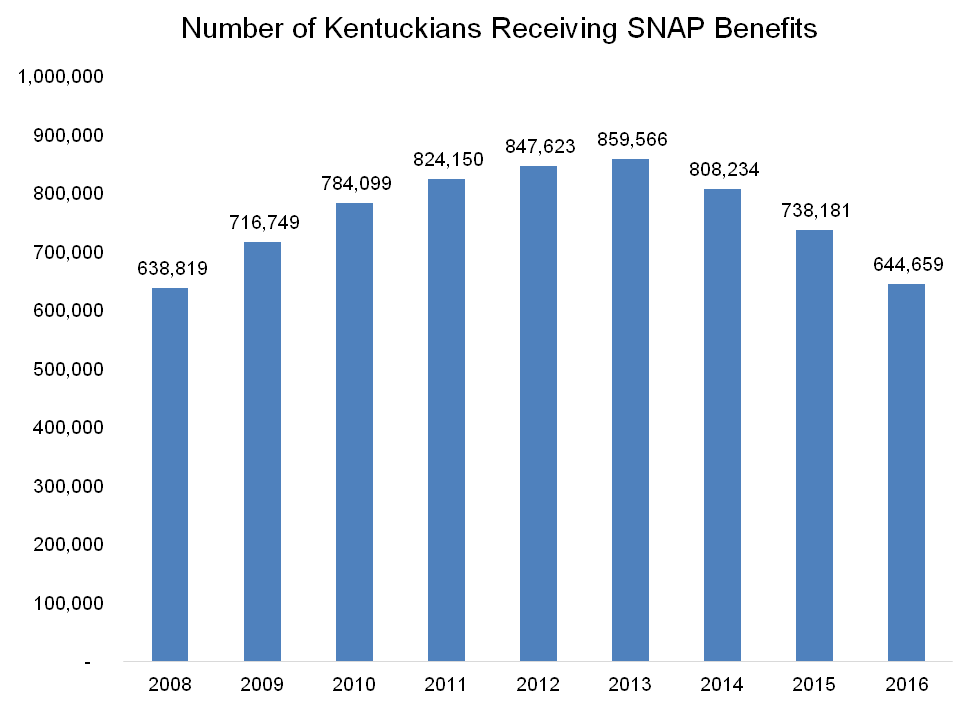

The recent history of SNAP in Kentucky makes this clear. Between 2008 and 2013 — as the Great Recession hit and its effects lingered — the number of Kentuckians receiving SNAP benefits increased by 221,000. But as the economy improved since then, the number of SNAP recipients fell by 25 percent and returned to its level before the recession hit.

Source: Cabinet for Health and Family Services.

Without SNAP kicking in, recessions would be deeper, longer and more painful. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reports, “after unemployment insurance, SNAP is the most responsive federal program providing additional assistance during downturns.”

This role for SNAP also extends to economic problems that crop up at a local level. While SNAP enrollment has fallen across the state since 2013, the decline has been greater in counties experiencing a more robust recovery while the program has continued to play a larger role in counties facing economic barriers.

Twenty Kentucky counties, many of them in central and northern Kentucky, have had a greater than 30 percent decline in SNAP enrollment over the last three years, even while many of those counties have had growing populations overall. In contrast, 10 eastern Kentucky counties have seen SNAP enrollment decline by a more modest 15 percent or less. And a number of eastern Kentucky counties — including Letcher, Harlan, Perry, Knott, Floyd and Pike — have more people receiving SNAP now than in 2008, despite population loss over that time in those areas.

The loss of coal jobs in those counties beginning in 2012, and the ripple effect in communities, plays a big role in that difference. SNAP picked up some of the slack in local economies and ensured many families could meet basic needs. But the lag in those counties — on top of the longstanding high poverty rates that existed in those places already — underscores the serious need for other public investments to help create jobs and transition the economy.

SNAP does its job very well. In addition to economic stimulus, it protects families from hardship and hunger, reduces the depth of poverty, supports employment and has low error rates and administrative costs. Kentucky would have much to lose if Congress pursues changing the structure of SNAP to a block grant, which would make it unresponsive to economic conditions, or if the state creates barriers to access this vital program.