Click for a PDF version of SNAP Is Good for Kentuckians’ Health.

Everyone knows that food is essential to well-being, but less widely understood is the power of direct food assistance in improving health. A growing body of research shows the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is an effective tool for addressing health problems that stem from food insecurity.

SNAP improves access to nutrition, increases the share of meals eaten at home and frees up dollars for other family needs that can improve health like better housing, utilities and prescription medicine. Research suggests it can actually contribute to lower health care spending, including by the state. By directly reducing hunger and combating poverty, SNAP helps people get and stay healthy. These findings are especially crucial in a state like Kentucky, where much has been made of our historically poor health — and for good reason.

SNAP’s importance relates in part to its broad reach: today roughly one in nine Kentuckians purchases groceries with assistance through SNAP and far more do during economic downturns including the most recent recession.[1] Yet SNAP’s ability to improve health is limited by state and federal policy decisions that are reducing SNAP participation. As research demonstrates SNAP’s power as an important health intervention, improving health in Kentucky means finding ways to ensure it is available to all Kentuckians who need it, rather than restricting its use.

SNAP Is a Needed Health and Hunger Intervention in Kentucky

Need to Address Health and Health Equity in the Commonwealth

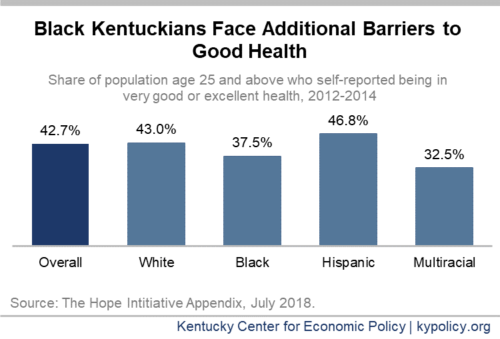

Kentucky’s starting point for health is low relative to most other states. In 2018, the state ranked 45th in the nation for overall health outcomes.[2] Less than half of Kentuckians over the age of 25 report being in very good or excellent health, as shown in the graph below. And due to a long history of systemic racism that is a barrier to good health (entrenched through policies and practices such as slavery, Jim Crow laws, racial redlining, and discrimination in schools and the workplace), black Kentuckians have even poorer health outcomes than white Kentuckians on average.[3]

Underlying Kentucky’s poor health indicators are factors that shape the opportunities to be healthy such as income, poverty, access to exercise opportunities and exposure to pollution.[4] Similarly, a lack of high-quality jobs, safe housing and clean water — for instance, in rural and especially the eastern parts of the state — mean that some Kentucky communities especially struggle with poor health.

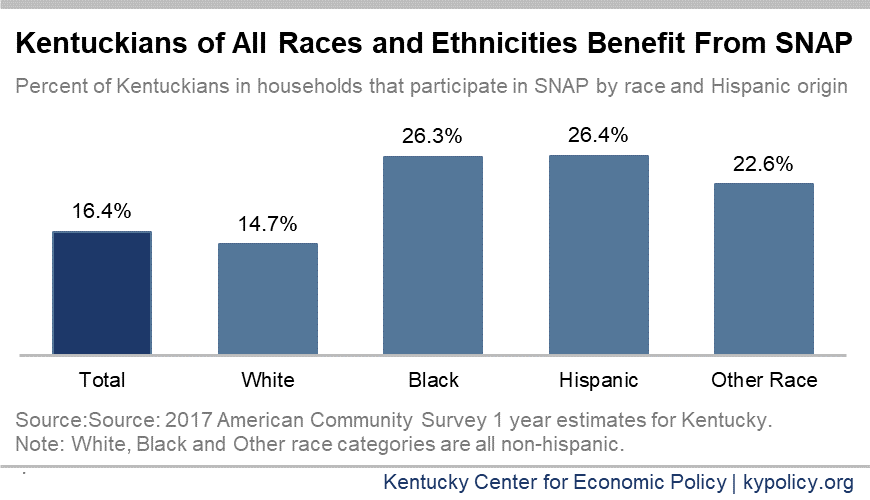

These “social determinants of health” are incredibly important to well-being, and while overall Kentucky is a high-poverty, low-income state, economic opportunity is not equally available to all Kentuckians. Historical barriers to good health have left Kentuckians of color, especially black Kentuckians, with higher rates of unemployment, lower wages and higher rates of poverty (which is 16.3% for white Kentuckians compared to 24.7% for African-American Kentuckians according to 2017 Census data).[5] While 76% of SNAP recipients in Kentucky are white, SNAP utilization rates are higher among black, Hispanic and other Kentuckians of color compared to white people, making the program a critical tool for mitigating the harmful consequences of systemic racism and promoting health equity.

There are also disparities for rural Kentuckians, particularly in the eastern part of the state that have not recovered from the Great Recession, and where historical economic hardships persist. The relatively higher rates of SNAP usage in eastern Kentucky counties are linked to longstanding structural challenges in a regional economy built around extractive industries that have now faded dramatically.[6] Consequentially, both unemployment and poverty levels – and therefore SNAP participation – remain higher than the rest of the state.

Food Insecurity is Pervasive in Kentucky, Especially in Economically Distressed Areas

Kentucky has the 8th-highest rate of food insecurity among states, with 14.7% of households being food insecure compared to the national average of 12.3%.[7] The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines food insecurity as simply not having enough food to eat, or having inadequate resources for food that reduce the quality, variety or desirability of the food purchased.[8] Within the state, the percent of the population that struggles with food insecurity ranges from an estimated 8% in Oldham County to 23.9% in Magoffin County. Nine of the top 10 most food insecure counties in Kentucky are in the rural eastern part of the state, with Fulton County in far western Kentucky being the one exception.[9]

Many studies have demonstrated the relationship between various economic factors and food security.[10] Most importantly, rates of food insecurity drop as the income-to-poverty level rises and even more so as rates of unemployment fall.[11] So for the same reasons SNAP participation rates are higher in eastern Kentucky counties, food insecurity also occurs at a higher rate.

Food Insecurity Is Bad for Health

There is an abundance of research showing that food insecurity contributes to poor health. Many studies show poor results for the food insecure generally, including higher rates of diabetes, stress and anxiety. A review of recent studies by Craig Gunderson from the University of Illinois in Urbana and James Ziliak from the University of Kentucky broke these findings down by age group, and found multiple health conditions closely linked to insufficient food.[12]

- Children – The findings from multiple studies showed that children who were food insecure were more likely to have anemia, tooth decay, asthma, behavioral problems, anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation than their peers who were not food insecure. Mothers who struggle to get enough food experience higher rates of depression and iron deficiency (among pregnant women), and their children tend to have higher rates of behavioral problems whether or not they themselves are food insecure. As of 2017, 258,000 Kentucky children participated in SNAP.

- Non-elderly adults – The reviewed studies showed that nonelderly adults who are food insecure tend to have a decreased nutritional intake and higher risks of mental health problems, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, poor sleep and poor oral health. In 2017, 317,000 non-elderly Kentucky adults participated in SNAP.

- Older adults – The three existing studies on how food insecurity affects the health of seniors found that food insecure seniors report comparatively lower nutrition intakes and higher likelihood of depression, limitations in activities of daily living and being in poor or fair health. One study showed that food insecure seniors had roughly the same quality of life as someone 14 years older. There were 63,000 Kentuckians over 60 years old in 2017 who participated in SNAP. [13]

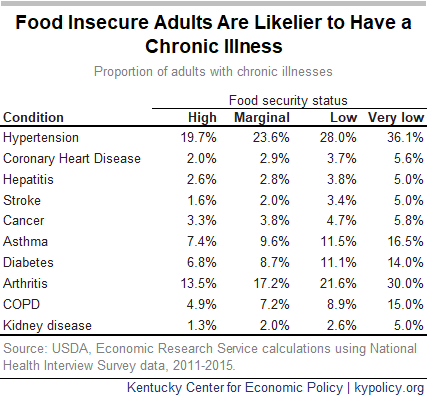

A separate study of adults ages 18-64 who earn at or below 200% of the poverty level found that food insecurity is closely related to the likelihood of having chronic illnesses, and the number of chronic illnesses a person has. In fact, across each level of food insecurity, the likelihood of having each of 10 chronic illnesses (listed below) increased.[14]

Food Insecurity Increases Health Care Costs

Though many harmful health effects of food insecurity are well documented, understanding how these effects are indicated in related health care costs was only recently estimated on the state and county level. According to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, food insecurity was associated with $1,834 in health care spending per food insecure adult nationally in 2016.

Kentucky alone spent $854.7 million on food insecurity-related health care that year. Kentucky’s per-capita health care spending related to food insecurity was 6th highest in the country at $194, but varied widely from county to county – from $98 in Oldham County to $400 in Clay County. The authors of the CDC report point out that only 40% of food insecure adults have private health insurance, so the remainder are covered by public health programs such as Medicaid or are uninsured altogether. Because food insecurity-related costs comprise 3%-6% of health care costs, the authors suggest that states could improve health and lower expenses in programs like Medicaid by making SNAP — which unlike Medicaid, is entirely federally funded — more widely available.[15]

SNAP Helps Put Food on Kentuckians’ Tables, Improving Food Security and Health

SNAP Participants Buy Groceries

In their report, Gunderson and Ziliak said “the most direct way to ameliorate the health consequences associated with food insecurity is to reduce food insecurity.” Because receiving food assistance helps families purchase groceries more consistently, SNAP-participating households tend to have more food security than similar households without the assistance – which contributes to their ability to get and stay healthy.

A 2013 USDA report followed households during their first 6 months of  using SNAP and found that food insecurity decreased by 16.3%.[16] A different study used data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation from the 1990s and 2000s to determine that participating in SNAP reduced the likelihood of being food insecure by 31.2% and the likelihood of being very food insecure by 20.2%.[17]

using SNAP and found that food insecurity decreased by 16.3%.[16] A different study used data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation from the 1990s and 2000s to determine that participating in SNAP reduced the likelihood of being food insecure by 31.2% and the likelihood of being very food insecure by 20.2%.[17]

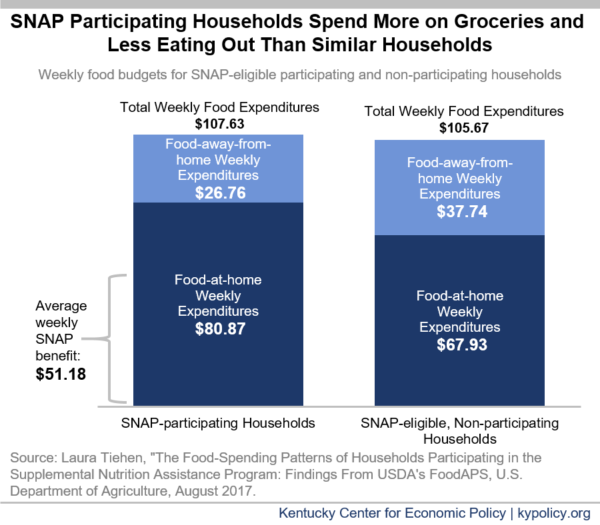

Not only does SNAP reduce food insecurity, but it may even improve the quality of food being purchased. Food prepared and eaten at home tends to be more nutrient-dense and healthier (based on federal nutrition guidelines) than eating out at restaurants.[18] There is evidence to suggest that when households receive SNAP, their overall food budget increases some, but their food at home budget increases substantially. According to a national study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), SNAP-participating households spend an average of $80.87 per week on groceries, of which $51.18 is through SNAP. These same households spend a greater share of their food budgets on groceries than eating out – 75% for SNAP participating households – compared to 64% for SNAP-eligible, non-participating households (and compared to 62% for SNAP ineligible households).[19]

According to survey data, people who live in SNAP-participating households are less likely to have purchased meals prepared outside the home such as deli, carry-out, delivery or fast food meals in the previous week (43.4%) than low-income SNAP nonparticipants (49.8%) and far less than the average adult (58.2%).[20]

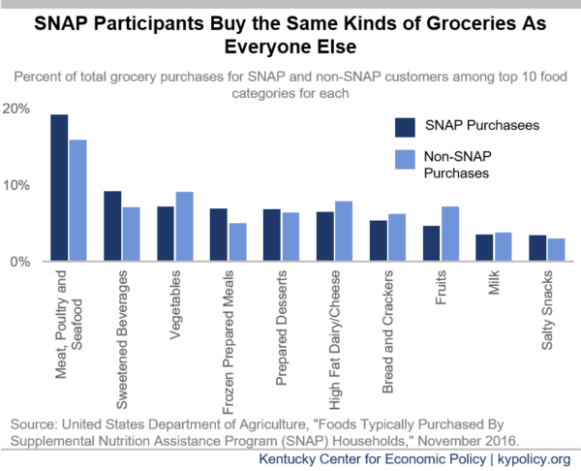

Contrary to stereotypes, the kinds of groceries for meals prepared at home that SNAP participants purchase (the only kinds of food that can be purchased through the program) largely reflect the grocery purchases made by the general public. The top ten food categories purchased by SNAP participants and non-SNAP participants are the same, but are not necessarily in the same order.[21]

SNAP Participation Can Reduce the Need for Health Care

There is an increasing body of evidence at the national level that shows a relationship between participating in SNAP and reduced health care costs. It is likely that SNAP lowers those costs in part by freeing up household resources for other expenses that contribute to better health, such as housing, utilities and prescriptions to manage chronic conditions. For example, evidence suggests that SNAP participation leads to a 30% reduction in the likelihood that seniors will cut back on needed medications.[22]

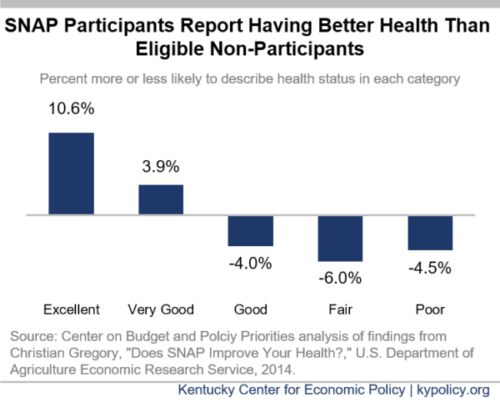

One study assessed SNAP participants’ self-reported health status. It found that, after adjusting for other factors shaping health, adults who participated in SNAP, compared to those who did not, were more likely to report having excellent or very good health, and less likely to report good, fair or poor health. They were less likely to stay home sick, visit the doctor or forgo care because of cost.[23]

Research has shown that after controlling for other factors, SNAP participants spend 25% less (around $1,400) on health care annually than similar non-participating adults. Those savings are even greater among individuals with more significant health conditions.[24] Another study found that increased SNAP benefits resulted in a decline of Medicaid cost growth by 73% through a reduction in hospitalizations and treatment for chronic illnesses.[25]

A 2018 study of older adults concluded SNAP receipt was associated with reduced hospitalization (-14%) and emergency room use (-10%). Additionally, “SNAP participants had a 10% lower likelihood for each additional inpatient day if hospitalized and a 4% lower likelihood of each additional emergency department visit if they utilized [SNAP].”[26] A separate study of older SNAP participants that compared them to other eligible but non-participating older adults showed an even more dramatic reduction in the likelihood of being hospitalized (-46%).[27]

There is even evidence that states with higher ratios of spending on social services like SNAP to spending on health care services like Medicare and Medicaid have better health outcomes. The study specifically looked at rates of adult obesity, asthma, mentally unhealthy days, days with activity limitations and mortality rates for lung cancer, heart attacks and type 2 diabetes. While the study didn’t suggest an ideal ratio, it did suggest that policy-makers need to think of social service spending as a form of public health intervention.[28]

SNAP Policy Choices Can Help or Hinder Health in Kentucky

To optimize SNAP as a tool for supporting and improving health in Kentucky, it needs to be robust, easily available to those who qualify and simple to use for those who participate. Regarding SNAP’s ability to reduce poverty, and thus improve health, one report on the health benefits of SNAP put it this way:

No other program for the nonelderly does such a great job preventing poverty or alleviating poverty’s weight on those who remain poor. We should be heralding and celebrating this success, not trying to reduce the program.[29]

SNAP enrollment in Kentucky has declined over 40% since the high point of July 2013 for a number of reasons, some of them concerning. Because SNAP is income-based (net income must be below the poverty level), it responds well to changes in the economy. As Kentucky continues to experience a historically long economic expansion and household finances marginally improve, enrollment has naturally declined. But participation has also dropped as the result of harmful policy choices the state has made.

Current and Potential Hindrances to SNAP in Kentucky Could Worsen Health

Recent administrative changes to SNAP have led to tens of thousands losing assistance and have likely increased food insecurity. The negative health impacts especially harm people of color and economically distressed communities facing other barriers to food security.

Specifically, two changes have led to nearly 25,000 people losing SNAP. First, state officials reinstated a strict work reporting requirement; between February and May 2018 this requirement was rolled out, and to date, 21,400 childless adults without a disability have lost food assistance.[30] Second, the state introduced an administrative regulation stripping food assistance from 3,500 non-custodial parents who were late on their child support payments.[31] Among those who lost benefits because of child support arrearages, 90% were in households where other members were still eligible for food assistance.[32] This meant that the overall food budget for those households shrunk, making it harder to afford food and dampening the health-boosting effect of SNAP in those homes.

Kentucky has also experienced a decline in the share of people technically eligible for SNAP who are actually receiving the benefit. That decline is the highest in the nation, according to a USDA analysis. From 2014 to 2016, the SNAP usage rate among eligible Kentuckians dropped from 85% to 74% — landing Kentucky at the tenth lowest participation rate in the country.[33] The state is doing a poorer job making sure that who should be receiving those benefits are actually doing so.

Other proposals have been floated in the legislature, in some cases repeatedly over the years, that would further undermine SNAP’s ability to promote good health in the commonwealth. Several proposals that would make it harder for Kentuckians to access SNAP were included in a recent bill – 2019’s House Bill 3 – but have long been debunked as effective policy:

- Requiring “workfare” for parents aged 19-64 with children over the age of 5 in order to receive SNAP benefits. Workfare is essentially an unpaid internship, which has no evidence of improving participants’ employment outcomes, but can reduce SNAP participation and leave individuals more food insecure.

- Requiring photographs of the SNAP user on the electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card. Photo IDs have been tried and abandoned in several states because they make it more difficult for family members to purchase household groceries and are a liability for grocery store employees who have to then check photo IDs for every customer using a card for purchases.

- Mandatory drug testing for anyone with a felony or misdemeanor history of substance abuse. The most recent version of this measure would have required participants to pay up front, and only be reimbursed if they passed the test. Effectively, this creates an application fee, possibly cost-prohibitive, for individuals who are already so low-income that they are seeking help to buy food.[34]

These proposals may continue to be considered in Frankfort for the foreseeable future. None of them would give low-income Kentuckians the tools necessary for good health, and by making it harder to buy food, would actually contribute to poorer health.

Recent federal SNAP policy proposals also jeopardize the health of Kentuckians by increasing food insecurity.

- The USDA has recently proposed to make it harder for states to waive the SNAP work reporting requirement, a change that would reduce the current number of Kentucky counties eligible for a waiver from 117 to 25.[35]

- The USDA also proposed a rule essentially bringing back an asset test through restricting the use of Broad-Based Categorical Eligibility (BBCE). Doing so would penalize Kentuckians who have acquired a modest amount of savings, thereby making it harder for SNAP participants to dig out of a financial hole. In Kentucky, 42,000 people would likely lose food assistance under this rule.[36]

- The Office of Management and Budget proposed to slow the inflation adjustment measure for the poverty line, which would gradually lower the eligibility threshold for many programs, including SNAP. If this lower rate of inflation had been used over the past 15 years, 4,000 fewer Kentuckians would have been participating in SNAP.[37]

Improving Access to SNAP Would Improve Health

To improve health in the commonwealth, Kentucky should begin by reversing harmful policies recently enacted and abandon attempts to erect new barriers to food security. We can also improve on Kentucky’s SNAP program in other ways:

- Kentucky has for a long time banned people from participating in SNAP if they have a drug-related felony conviction on their record. Individuals can have the ban lifted if they prove they had an addiction that has been treated, but it is not clear how many do. In 2018, 1,273 Kentuckians lost their food assistance due to this rule (many more may have been denied SNAP due to this rule while applying). Among those who lost SNAP, 965 lived in a household with other people, meaning the entire household had less money for groceries overall.[38] A universal end to the ban would ensure that more people re-entering society have enough to eat and can build a healthy life for themselves and their families.

- Currently Kentuckians must go through a SNAP eligibility redetermination process every 4 to 12 months, depending on age and if the work reporting requirement applies. But the USDA gives states the option of requiring redetermination every 12 months for all Kentucky households and up to 24 months for households where elderly people and people with disabilities live. Such a change would provide for as little disruption as possible when using SNAP, and could provide longer periods of food security. More food security means more opportunity for good health.

- The state also has more stringent penalties for people who lose their SNAP benefits because of the work reporting requirement, which could be re-set to the federal minimum. In doing so, some of the harshness inherent in Kentucky’s decision to reinstate the time limits for all but a handful of counties would be reduced, allowing low-income Kentuckians to begin using food assistance again more quickly.

- Kentucky could also extend BBCE to apply to gross income (the net income standard wouldn’t change) in addition to assets, as is currently the case. This would allow more people to be screened for eligibility, and phase out benefits starting from a higher income, allowing people to earn more without losing benefits as quickly.[39]

[1] Data from the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services (CHFS).

[2] United Health Foundation, “American’s Health Rankings 2018 Annual Report,” https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/Overall/state/KY.

[3]N. Siddiqui et al, “The HOPE Initiative: Appendix,” National Collaborative for Health Equity, July 2018, http://www.nationalcollaborative.org//www/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/HOPE-Appendix-Final-07.24.2018.pdf.

Office of Health Equity, The Department for Public Health, The Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, “2017 Kentucky Minority Health Status Report,” http://www.astho.org/Accreditation-and-Performance/Documents/HE-Issue-Brief/KY-2017-Minority-Health-Status-Report/.

[4] County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, “Kentucky: 2019 County Health Rankings Report,” March 2019, http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/state/downloads/CHR2019_KY.pdf.

[5] Dustin Pugel, “Systemic Barriers Continue to Hold Back Wages and Employment for Kentuckians of Color,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jun. 19, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/systemic-barriers-continue-to-hold-back-wages-and-employment-for-kentuckians-of-color/.

[6] Jason Bailey, “The State of Working Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 28, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/the-state-of-working-kentucky-2018/.

[7] Alisha Coleman-Jensen, “Household Food Security in the United States in 2017,” United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, September 2018, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90023/err-256.pdf?v=0.

[8] Christian Gregory and Alisha Coleman-Jensen, “Food Insecurity, Chronic Disease, and Health Among Working-Age Adults,” United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, July 2017, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84467/err-235.pdf?v=42942.

[9] Data from Feeding America’s 2016 county-level estimates of food insecurity, https://www.feedingamerica.org/research/map-the-meal-gap/by-county.

[10] Craig Gundersen, Brent Kreider and John Pepper, “The Economics of Food Insecurity in the United States,” Applied Economic Perspectives Volume 33, Issue 3, 2011, https://academic.oup.com/aepp/article/33/3/281.

[11] Craig Gundersen et al, “Map the Meal Gap 2018: Technical Brief,” Feeding America, 2018, https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/research/map-the-meal-gap/2016/2016-map-the-meal-gap-technical-brief.pdf.

[12] Barbara Laraia, “Food Insecurity and Chronic Disease,” Advances in Nutrition, Mar. 1, 2013, https://academic.oup.com/advances/article/4/2/203/4591628.

Craig Gundersen and James Ziliak, “Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes,” Health Affairs, November 2015, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645.

[13] United States Department of Agriculture, “Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2017,” February 2019, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/Characteristics2017.pdf.

[14] Christian Gregory and Alisha Coleman-Jensen, “Food Insecurity, Chronic Disease, and Working-Age Adults.”

[15] Seth Berkowitz et. al, “State-Level and County-Level Estimates of Health Care Costs Associated with Food Insecuirty,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Jul. 11, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2019/18_0549.htm#Appendix.

[16] James Mabli et al., “Measuring the Effect of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participation on Food Security,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Food and Nutrition Service Office of Policy Support, August 2013, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/Measuring2013.pdf.

[17] Caroline Ratcliffe et al., “How Much Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Reduce Food Insecurity?” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Jul. 12, 2011, https://academic.oup.com/ajae/article-abstract/93/4/1082/203719?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

[18] Michelle J. Saksena et al., “America’s Eating Habits: Food Away from Home,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, September 2018, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90228/eib-196.pdf?v=1045.6.

[19] Shaheer Burney, “In-kind Benefits and Household Behavior: The Impact of SNAP on Food-away-from-home Consumption,” Food Policy, February 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.01.010.

[20] Eliana Zeballos and Brandon Restrepo, “Adult Eating and Health Patterns: Evidence From the 2014-16 Eating & Health Module of the American Time Use Survey,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, October 2018, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90466/eib-198.pdf?v=2608.6.

[21] Steven Garasky et al, “Foods Typically Purchased by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Households,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Nutrition Service, November 2016, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/SNAPFoodsTypicallyPurchased.pdf.

[22] Mithuna Srinivasan and Jennifer Pooler, “Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence for Older Adults Participating in SNAP, 2013-2015,” American Journal of Public Health, Oct. 9, 2017, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304176.

[23] Steven Carlson and Brynne Keith-Jennings, “SNAP is Linked with Improved Nutritional Outcomes and Lower Health Care Costs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Jan. 17, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/1-17-18fa.pdf.

[24] Seth Berkowitz et al., “Impact of Food Insecurity and SNAP Participation on Healthcare Utilization and Expenditures,” University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research, 2017, https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1105&context=ukcpr_papers.

[25] Rajan Anthony Sonik, “Massachusetts Inpatient Medicaid Cost Response to Increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Benefits,” American Journal of Public Health, March 2016, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4880217/.

[26] Laura Samuel et al., “Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Affect Hospital Utilization Among Older Adults? The Case of Maryland,” Population Health Management, Apr. 1, 2018, https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/pop.2017.0055.

[27] J. Kim, “Are Older Adults Who Participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Healthier Than Eligible Nonparticipants? Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study,” The Gerontologist, Nov. 1, 2015, https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article/55/Suppl_2/672/2489236.

[28] Elizabeth Bradley, et al., “Variation in Health Outcomes: The Role of Spending on Social Services, Public Health, And Health Care, 2000-09,” Health Affairs, May 2016, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0814?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed.

[29] Laura Tiehen et al. “SNAP Matters: How Food Stamps Affect Health and Well Being,” Stanford University Press, 2016, p. 68.

[30] Dustin Pugel, “Reinstating Time Limits for Food Assistance Will Hurt Low-Income Kentuckians and Local Economies,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 26, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/reinstating-time-limits-food-assistance-will-hurt-low-income-kentuckians-local-economies/.

[31] Darla Carter, “More than 21,000 Kentuckians Lose Food Aid Due to Work Requirement, Groups Say,” Insider Louisville, May 16, 2019, https://insiderlouisville.com/government/more-than-21000-kentuckians-lose-food-aid-due-to-work-requirement-groups-say/.

[32] Jason Dunn, “Death By a Thousand Cuts: 3,500 Lost Food Benefits So Far in 2019 for Being Behind in Child Support,” Kentucky Voices for Health, Jun. 11, 2019, https://www.kyvoicesforhealth.org/single-post/2019/06/11/Death-by-a-Thousand-Cuts-3500-lost-food-benefits-so-far-in-2019-for-being-behind-in-child-support.

[33] Karen Cunnyngham, “Reaching Those in Need: Estimates of State Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participations Rates in 2016,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, March 2019, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/Reaching2016.pdf.

[34] Dustin Pugel and Ashley Spalding, “HB 3 Proposes Massive, Expensive and Ineffective Bureaucracy That Will Hurt Kentucky Families and Open State to Legal Problems,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Mar. 4, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/hb-3-proposes-massive-expensive-and-ineffective-bureaucracy-that-will-hurt-kentucky-families-and-open-state-to-legal-problems/.

[35] Dustin Pugel, “Evidence from Kentucky Should Serve as Warning Against Food Assistance Restriction Rule,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Apr. 4, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/evidence-from-kentucky-should-serve-as-warning-against-food-assistance-restriction-rule/.

[36] Jessica Klein, “Eliminating SNAP Broad-Based Categorical Eligibility Increases Inefficiencies and Hunger for Working Families, Older Adults and Persons with Disabilities,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sep. 24, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/eliminating-snap-broad-based-categorical-eligibility-increases-inefficiencies-and-hunger-for-working-families-older-adults-and-persons-with-disabilities/.

[37] Dustin Pugel, “Change to Poverty Measure Would Mean Hardship for Many Kentuckians,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jun. 20, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/change-to-poverty-measure-would-mean-hardship-for-many-kentuckians/.

[38] Data from an open records request to the Kentucky Department for Community Based Services fulfilled on May 14, 2019.

[39] USDA Food and Nutrition Service, “State Options Report: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Fourteenth Edition,” May 2018, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/snap/14-State-Options.pdf.