Although substantially changed, the newest Senate version of House Bill 7 (HB 7) still puts up numerous paperwork barriers to food and medical assistance for Kentucky families and workers. HB 7 adds new, more stringent reporting requirements and restrictive eligibility criteria that establish an “unwelcome mat” posture toward Kentuckians who need help with food and medicine.

Many of these components would run afoul of federal law, and all of them would cost a considerable amount in state resources just to get in the way of delivering vital assistance. In some portions of the bill, the language is unclear in ways that will make implementation difficult, making it confusing for applicants of programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid to successfully navigate them. The bill’s byzantine, costly, disproven focus on punishing accusations of fraud — shown time and again to be extremely low among public assistance participants — will cause tens of thousands of eligible Kentuckians to lose help with the foundations of well-being and economic security, and scare many more to avoid seeking help in the first place.

New version of HB 7 has paperwork barriers that will keep Kentuckians from accessing help with groceries

HB 7 prohibits the state from giving food assistance to certain adults in economically distressed areas, even during downturns.

Non-disabled Kentucky adults who don’t have dependents can receive SNAP benefits while out of a job for only 3 months out of a 36-month period. However, the federal government allows states to waive that time limit, recognizing that finding a job during a downturn or in an economically distressed county is difficult, and that SNAP can act as an economic stabilizer. The entire country waived the requirement during the Great Recession and then again during the COVID-19 downturn.

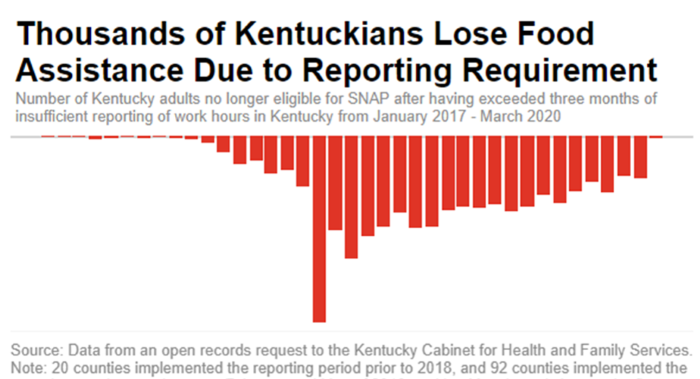

But HB 7 would take away the ability of the state to waive time limits unless the county or state unemployment rate is over 10% — so high that as of February, only two Kentucky counties would currently be exempt, despite many areas where jobs are still difficult to find. This provision would push adults and their households deeper into food insecurity and poverty while harming local economies. During the years Kentucky was recovering from the Great Recession, these waivers expired in most counties, ultimately leading to 33,399 Kentuckians losing food assistance. Estimates from CHFS are that 30,000 Kentucky adults would likely lose food assistance within just 3 months of the implementation of this provision.

That lowered the total grocery money available to others who lived in their households and pulled millions out of local economies — creating a ripple effect as $1 spent on SNAP generates nearly $2 in the broader economy. If HB 7 passes, counties in eastern Kentucky will be especially harmed, as jobs are scarce in those counties and workers there have a harder time finding work than the rest of the state. Now they will have a harder time affording food, too.

HB 7 bans the state from providing exemptions to the SNAP time limit for those in extraordinary circumstances.

For those slated to lose food assistance because of the SNAP time limit for certain jobless adults described above, the state can step in to exempt a limited number of cases when there are extraordinary circumstances. This ensures that when folks hit a bump in life outside their control, their situation isn’t exacerbated by taking away help with groceries as well.

By both banning waivers in areas that are economically distressed, and then also not allowing for individual extenuating circumstances to be considered, HB 7 creates a rigid, one-size-fits-all time limit for jobless Kentuckians seeking help with food. And just like the ban on waivers, this will not only hurt those who have their SNAP benefits revoked, but others in their household, local grocery stores and the broader economy as well.

HB 7 could mandate participating in an inadequate number of Education & Training programs.

Many working adults without dependents or disabilities participate in SNAP; the abundance of poverty-wage jobs in Kentucky means they do not make enough to put food on the table. In addition to requiring them to report that work, HB 7 could lead to a requirement that these Kentuckians, an estimated 68,000 people (including individuals without dependents or disabilities up to age 49, as well as adults up to age 59 with dependents over 5 years old) to participate in a SNAP Employment and Training program, known as SNAP E&T. Despite efforts in the past decade, E&T infrastructure is wholly inadequate, with only 1,200 slots according to Cabinet for Health and Family Services (CHFS). Though HB7 would also create online options, given the few spots open to the immense number of those who would be required to participate, many Kentuckians would have to travel a good distance to access opportunities that are few and far between across the state, even as the program lacks any kind of transportation support.

HB 7 creates new penalties on all assistance based on fraud accusations.

HB 7 creates a three-strike ban that would keep people from getting needed help — Medicaid, SNAP, TANF and any other assistance program in Kentucky — for up to 5 years for making a mistake or selling benefits from their EBT card. All of these programs are jointly run by the state and federal government and each one comes with its own federal rules for implementation. It is not clear that the cabinet could implement a ban across all programs without running afoul of various laws governing each program. Additionally, a new penalty in the Senate’s version of HB 7 creates a fee up to $500 for an initial accusation of fraud for how they decide to use their cash assistance to care for their family, by people that receive TANF — an amount almost equivalent to a month’s paycheck for many of the participants of this program for families with low-incomes. Additional accusations could lead to up to a year ban from receiving cash assistance for these families.

Federal research shows that the real fraud rate for SNAP is less than 2%. Despite that low rate, many more people are suspected of trafficking their card based on mistakes that are easy to make while using a card, such as entering in the wrong pin number too many times, shopping at the same store more than once in a day or having a purchase ending in a whole-dollar amount. These mistakes are monitored by imperfect algorithms created by the USDA and Deloitte that mark mistakes as red flags for fraud. With an algorithm’s red flag as the determining source for fraud, a new mom making a mistake while using her SNAP card, for instance, could result in her being banned for life from things like child care assistance all the way to help with medical bills through Medicaid when she is a senior.

New version of HB 7 has paperwork barriers that will prevent help with medicine and doctor visits

HB 7 sets up income verification tripwires to losing Medicaid.

HB 7 sets up a more frequent, quarterly review of various databases that keep information related to Medicaid eligibility, including income, and it requires that the most recent income data available is used for Medicaid eligibility purposes (instead of an average income over a period of time, or a “look-back period”). These will increase administrative burden, as well as churn and disenrollment from Medicaid.

But by using the latest income data available instead of the current process of using a broader look-back period, the cabinet would exclude from eligibility (or even improperly determine eligibility for) people with irregular incomes. Farmers and independent contractors, for example, are often paid in irregular, large lump sums, but earn below the income eligibility limit over a year. If they apply for Medicaid shortly after being paid, they may be found ineligible because they appear to have too much income. Having this process occur on a quarterly basis will create significant churn in Medicaid participation, and make it nearly impossible for impacted workers to receive continuity of care.

Further, it’s already the case that changes to Medicaid participants’ income often trigger a request for information from the cabinet. If a participant doesn’t give the state the information they asked for within a 30-day time limit, the Medicaid enrollee loses coverage. In fact, data from the Department of Medicaid shows that a failure to return paperwork on time was the most frequent reason why Medicaid enrollees lost coverage before the special COVID-era protections went into place in April 2020 (not reasons related to eligibility). Under HB 7, increasing the frequency of paperwork requirements to a quarterly basis will escalate paperwork-based Medicaid disenrollment.

HB 7 takes away the ability of applicants of public assistance to attest to certain details about their life.

All applicants of public assistance programs, including Medicaid, SNAP and the Kentucky Children’s Health Insurance Program, must have various details about their income, work and household members verified through documentation or database checks. But they can often get the process started through simply attesting to details like how many children they have, what their address is, or what their income is.

HB 7 would ban this practice for several public assistance programs. It would require, instead, that documentation be presented initially to prove these things before the process could continue, significantly slowing down the application and redetermination procedures and creating more opportunities for losing health coverage and other forms of assistance simply due to a paperwork issue. The exception to this would be those seeking coverage of long-term care in a facility, though they would be fined $500 each time they “willingly and knowingly” self-attest to falsified information.

HB 7 still bans state-determined, temporary “presumptive eligibility” Medicaid.

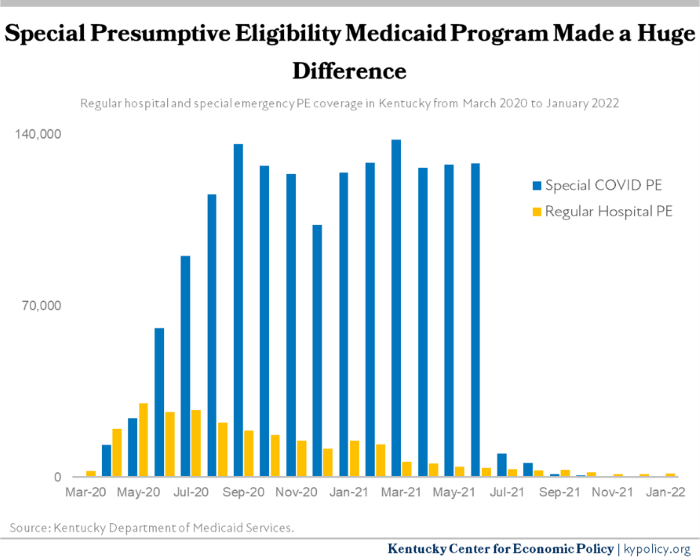

During the pandemic, Kentucky (along with many other states) was given permission by the federal government to offer health coverage for up to six months to Kentuckians who recently became uninsured. In doing so, CHFS extended a lifeline to hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians, while also keeping hospitals from closing their doors. But because this coverage is temporary, in July 2021 nearly 120,000 people rolled off of it, and now very few people use it while they apply for full Medicaid or seek coverage elsewhere.

Banning the state from being able to provide presumptive eligibility Medicaid means that when the next economic downturn hits and tens or hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians lose their health coverage as they are laid off from work, Kentucky will have no tools to quickly offer health insurance. Kentuckians will be forced to pay for the full cost of medicine out of pocket or forego seeing their doctor, and hospitals will face hobbling levels of uncompensated care — particularly rural hospitals.

There are still enough harmful provisions in HB 7 to throw tens of thousands off food and medical assistance

Many measures still in HB 7 — and the new provision forcing the cabinet to request an illegal work requirement — will harm Kentuckians who use Medicaid for their health coverage. Many measures still included — such as limitations on time limit waivers, potential education and training requirements and cross-program bans for fraud accusations — will take food assistance from Kentuckians who need it. Under HB 7, Kentuckians living in economically distressed counties will lose the help with groceries that they and their children need. With fewer Kentuckians with SNAP, schools’ automatic eligibility for free school meals and child care meal reimbursements will be put at risk.

If HB 7 is passed, Kentuckians will get caught up in an administrative maze of paperwork and eligibility requirements. Many who are working multiple jobs and providing care to loved ones in challenging contexts will simply turn away before even starting in order to preserve their time and mental well-being. The Senate should protect their constituents by rejecting this complex, expensive and harmful legislation.