Kentucky families need high-quality early child care and education to provide a safe learning environment for children at a critical age of development. Child care also makes parents’ and other guardians’ workforce participation possible, generating benefits for our economy as a whole.1 Yet high-quality child care is prohibitively expensive for many families, is difficult to find and pays its workers very little. We have long treated child care like a market, a model that has failed miserably in Kentucky. Further public funding is necessary to make operations sustainable for the industry and its workforce, and to make high-quality care accessible and affordable to Kentucky families.

Note: This report is available as a PDF here.

Recent federal COVID relief packages have improved the state-level Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) in key ways and provided direct support to child care providers, offering a proof-of-concept for what a permanent, publicly supported child care system could look like in Kentucky. The state desperately needs Congress to provide the substantial, permanent increase in federal funding for child care through the Build Back Better Act now under consideration. Kentucky state lawmakers should prepare to partner in implementing that expansion and building much more robust and secure early child care and education system.

High-quality child care is good for kids, but unaffordable for most parents

High-quality early child care and education is one of the most powerful investments we can make in a child’s life. Substantial brain development takes place in the first few years of life, with much of the critical neuropathways created by age three.2 Programs that offer high-quality care and education to young children have been shown to provide significant economic, social and health benefits among the children who participate, including fewer teenage pregnancies/delayed parenthood, higher likelihood of attaining a high school diploma and bachelor’s degree, more stable employment, higher earnings, a lower likelihood of becoming justice-involved, less reporting of depression symptoms, and a reduced likelihood of hypertension, metabolic syndrome and coronary heart disease.3

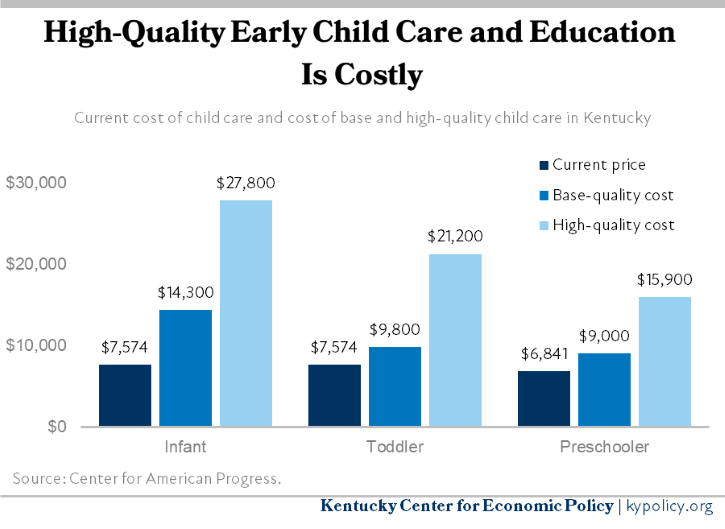

The goal of any state or federal policy should be to achieve these outcomes for all children. At current levels of public investment, however, high-quality programs are too few and too costly for most families to access. Small student-teacher ratios, well-trained instructors, planning time for teachers, larger and better-resourced learning environments and high pay to reduce turnover are all essential components of good early child care and education.4 However, the related costs combined far exceed current market rates. For example, the Center for American Progress compared current child care costs in Kentucky with what it would take to provide a base level of quality that meets minimum licensing standards for the state, and a high level of quality that incorporates the aforementioned components. They found even the base quality standard is much costlier than current average market rates in Kentucky, with the high-standard model costing 3.7 times the current cost.

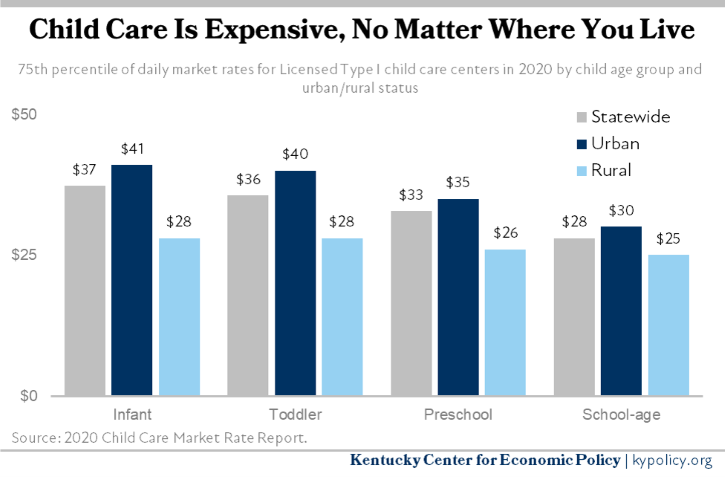

Putting quality aside, child care is still unaffordable for Kentucky families. As shown below, while market rates differ based on where a child care center is located, the age of the child being cared for and what type of center is providing the care, child care is already a major and often unaffordable expense for most families. Currently, the average cost of full-time child care in a mid-to-large-sized licensed child care center (known as Licensed Type I) for toddlers in Kentucky is $35.55 per day.5 At 5 days a week, 50 weeks per year, that amounts to nearly $8,890, which is 17.0% of the state median income (SMI, which was $52,295 for a household in 2019).6 That amount is far more than full-time tuition at a Kentucky Community and Technical College ($5,370 per academic year) and nearly as much as a full-time student pays for tuition at Western Kentucky University ($10,992 per academic year).7

This large expense often comes at a time when parents are still early in their careers, near their lowest earning years, and when necessary expenses like housing costs and student loans are near their highest. In fact, family net wealth is at its lowest on average during the first five years of the first child’s birth.8

When families can’t afford care, child care job quality is artificially low

Child care workers are the key to this crucial service, yet families’ inability to afford care even at market rates results in low job quality and high turnover. Average annual pay for child care workers in 2020 in Kentucky was $20,423, under the poverty line for a family of three ($21,960) and making the average child care worker eligible for CCAP themselves.9 10 Over one in four Kentucky early childhood educators have earnings below the poverty line.11 Nationally, child care workers earn less than 98% of all workers in the country, and in Kentucky, child care workers have among the highest student debt loads relative to their median earnings.12 These extremely low wages fall especially hard on women who comprised more than 9 out of 10 child care workers in 2019, and Black women who are disproportionately likely to work in child care.13

Owing in great part to poor job quality, prior to COVID, an estimated 26% to 40% of child care staff left their jobs each year.14 This turnover is costly and disruptive, and employers struggle to attract and retain new teachers. COVID has only exacerbated these challenges.15 In 2019, there were 12,185 Kentuckians who worked in the child care sector, but following the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic downturn, that number has fallen to 9,440 — a one-year reduction in the workforce of 22.5%.16

Child care capacity in Kentucky is inadequate

These child care workforce problems are part of the broader financial challenges of the industry as a whole. Half of Kentuckians live in a child care desert, which is defined as any area with more than 50 children under age 5 where there is either no child care provider, or there are three times as many children as there are available licensed child care spots.17

In Kentucky, an estimated 48.4% of children ages 0-5 were cared for by someone other than their parent for 10 hours or more each week in 2016, which was lower than the national average of 58.7%. An estimated 27.0% of Kentucky children ages 0-4 were in some form of paid child care, compared to 32.2% for the U.S. Nationally, children under 5 from wealthier, white and more educated homes were more likely to be placed in regular care by someone other than their parents, pointing to a need for financial assistance to remove barriers to care for families of color and those with lower incomes.18

In the 2019-2020 school year, 45,836 young Kentucky kids were in a publicly subsidized early childhood care or education setting:

- 10,237 were enrolled in Head Start or Early Head Start.

- 23,498 were enrolled in public preschool (5,865 of these were also in Head Start).

- 17,966 were enrolled in CCAP.

Also in the 2019-2020 school year, there were 220 certified family child care homes with an average capacity of 6 children per home, and 1,747 licensed child care centers, with an average capacity of 87 children per center.19

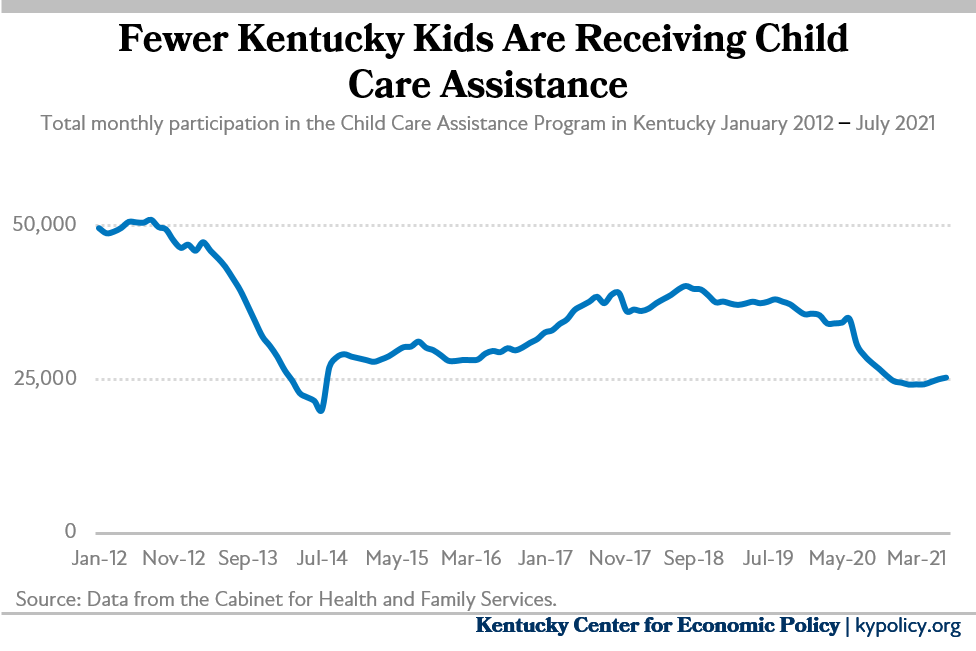

Difficulty in finding child care has been driven by the decrease in the number of child care providers in the state, and that decline can be partially attributed to changes in Kentucky’s child care assistance program. CCAP provides a direct payment from a state agency to a child care provider on behalf of a participating child from a working family with low wages, and is funded by a mixture of federal funds through the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) and state funds.20 In 2013, facing significant budget shortfalls, state leaders decided to place a moratorium on CCAP and lowered the eligibility threshold from 150% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) to 100%.21 Participation immediately began to decline, with 16% lower participation by August of that year. By July of the following year, participation had fallen by 27,000 children, or 57.5%.22 While enrollment has since risen, it has never returned to pre-2013 levels. Fewer CCAP funds flowing into child care facilities has made it harder for them to keep their doors open.

The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic downturn have only exacerbated difficulty in finding child care, demonstrated by a second major decline in CCAP participation, which is now roughly half of what it was in 2012. Nationally, as of May 2021, prime-age (25-54 years old) working parents of pre-kindergarten-age children have been more likely to report a recent loss of income (25%) than similar working parents of school-age children (21.6%) or workers without children (18.9%), suggesting they have had to stay home due to disruptions in child care. For prime-age working parents of color, the problem is far worse, with 36.1% of Black parents and 37.6% of Hispanic parents of pre-kindergarten-age children reporting losses of income.23

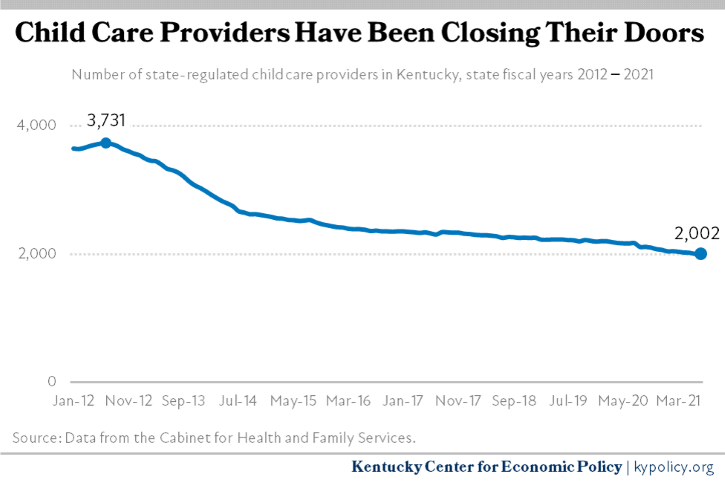

As a result of these shocks to the child care industry, total child care capacity has fallen for nearly a decade. As the graph below shows, child care centers began closing before the 2013 moratorium, but accelerated under it and slowed once it ended August 2014.24 The result is that Kentucky had 1,729 fewer child care centers in July 2021 than in July 2012, a decline of 46%. This long-term decline has left all Kentucky families, not just those participating in CCAP, with great difficulty in finding child care.

CCAP aids families, child care centers and the economy, but more funding is needed

In order to qualify for CCAP, Kentucky families must fall below 160% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) or $42,400 for a family of 4 in 2021.25 Parents must also be working, looking for work, or enrolled in specific educational programs to receive the assistance. While a family is participating in CCAP, their incomes are allowed to rise up to 200% FPL without losing the assistance.

The state reimburses child care providers for each child participating in CCAP based on:

- The county where the provider is located,

- The age of the child (infant/toddler, preschool, and school-age),

- The category of child care provider (center-based, certified family homes, etc.),

- If the child attends part-time or full-day,

- And the quality rating of the provider based on the All-STARS rating system, which judges the level of family and community engagement, staff qualifications, classroom/instructional quality and administrative/leadership practices.26

In the 2021 regular session of the Kentucky General Assembly, the provider reimbursement amount was raised by an average of $2 per day, per child thanks to House Bill (HB) 405, so that now reimbursement rates can be as high as $47 per child, per day and are very close to the recommended 75th percentile of market rates.27 But the state reimbursement does not amount to the full cost of providing care; families are required to pay a copay which also varies based on the number of children in the home and the income of the family, and can range from $0 to $25 per day.28 Additionally, if the combined state reimbursement and family copay doesn’t amount to the provider’s private-pay rate, providers are allowed to charge participating families “overages” to make up the difference.

Despite there being 325,900 children under 6 in Kentucky in 2019 — 126,900 of whom were in families with incomes below 160% FPL — just over 25,000 Kentucky children participate in CCAP.29 The vast majority of CCAP-participating children are ages 0-5, and all families paid an average daily copay ranging from $6.96 and $7.98 depending on the age of the child in February 2020 (the last month before the pandemic, before family copays were waived).30 The median amount of time a Kentucky family participates in CCAP is 6 months, which can be partially attributed to a low income threshold and a complicated enrollment process. This short timeframe for participation is disruptive for families who benefit from consistency in both the financial subsidy represented by child care assistance and in the stability of care provided to a child.31 And it also limits resources available to child care centers through CCAP.

Reflecting the inadequacy of CCAP as well as its underutilization, public subsidy only comprises 34.7% of child care provider revenue in Kentucky (slightly less than the 37.3% average among states), meaning the bulk of the cost burden falls on parents. In Kentucky, this combination of payers amounted to $477 million in revenue for child care centers, of which $208 million was paid out in earnings to workers in the child care industry in 2017. The child care industry has a profound effect on the broader community, leading to nearly $2 in economic activity for every $1 spent on child care. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that more widely available and affordable child care can contribute to a higher labor force participation rate, as it relieves parents (often women) of child care responsibilities.32 The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent downturn provided a clear illustration of this challenge, as school and child care closures disproportionately forced women out of the workforce and into uncompensated caretaking responsibilities.33

COVID-19 federal relief and state flexibilities helping keep child care capacity from collapse

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, when there were widespread school and business closures, and student-to-teacher ratios at child care centers were reduced in an effort to prevent infections, many child care providers found it financially and logistically difficult to operate. As a result, many closed their doors while others barely survived. To help alleviate some of those burdens, three major federal relief packages provided financial support for the child care industry. That funding allowed the Kentucky Division of Child Care to make helpful changes to child care policy to assist both providers and parents who struggled in the midst of a pandemic and economic downturn.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was the first of these bills, passed in March 2020. It sent $67.7 million to Kentucky’s CCDBG in mid-2020.34 This funding was primarily used for worker bonuses, cleaning stipends, and two rounds of sustainment stipends of $225 and $130 per child to help child care providers stay afloat.35

The Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA) was passed in December 2020, and provided over three times more funding for child care at $192.6 million.36 The vast majority of this funding ($165 million) was used for additional sustainment payments over the course of six months in four payments totaling $1,080 per child. This funding was used by providers for regular payroll, bonuses and fixed costs like rent, PPE, utilities, insurance and food. The remainder of that funding was used for enhanced background checks and trauma-informed care training for child care workers. The state also used this money to waive parental copays through the end of 2021, removing a barrier to participation in CCAP.37

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) had an even larger positive impact. It has provided Kentucky with $763 million in two separate funding sources: $470 million in stabilization grants, and a $293 million increase in Kentucky’s CCDBG. The stabilization grants are being paid on a per-child basis and will be distributed quarterly through September 2023 to all centers that meet minimum Labor Cabinet requirements, child care regulatory requirements and participate in the All-STARS program (a quality-rating system run by the state). Those payments will be increased 10% for centers whose starting pay is $10 per hour, and 20% for centers with starting pay at $13 per hour.38

The ARPA increase in CCDBG funding will be used for several initiatives through 2024, when it must be spent. Those include:

- Increased initial income eligibility to 200% FPL until 2023 or until that funding has been spent.39

- A public preschool partnership program wherein child care providers and public preschools work together to provide full-day settings (a program the General Assembly has provided pilot funding for in the past).

- Higher CCAP reimbursement rates and a more gradual phase-down in the subsidy for participants who no longer qualify.

- A pilot project that increases reimbursements for infant and toddler care given the higher level of pay for those child care workers.

- Funding for facility repairs and improvements.

- A training program related to caring for children with special needs and improving director skills.

- Child care apprenticeships for various positions.

- An early childhood education scholarship program.

- A new statewide child care data system, a state-funded billing and enrollment system for child care providers and new computers for child care centers for enrollment, billing and business needs.

- Startup grants for new family child care homes, businesses creating on-site child care settings and new center-based care centers in child care deserts.40

The ARPA funding through stabilization grants and a large boost in the state’s CCDBG will put Kentucky child care providers in a good position to recover well from the 2020 downturn, and could boost child care quality and capacity for years to come. But those grants run out in three years, and more needs to be done in order to sustain those improvements.

Kentucky can benefit from transformative improvements if Congress passes the Build Back Better Act

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how essential child care is to the economy and children’s wellbeing, and also how public investment is badly needed to support the industry. We cannot return to the failed market-based model of the past that resulted in little access to care, unaffordable costs, and poor job quality. Investments and policy improvements at both the state and federal levels can make quality child care affordable, available and sustainable in Kentucky.

The Build Back Better plan now in front of Congress includes funding for a child care entitlement and universal preschool that would make quality care and education for Kentucky kids age 0-5 more available and affordable. These investments have the potential to greatly benefit kids, parents, child care workers and our economy.

For children 3 and 4 years old, the Build Back Better plan creates a free, universal preschool program that could be implemented through public schools, licensed child care programs, Head Start grantees, or a combination of those entities. In the first three years in the current version, the federal government would pay $4, $6 and $8 billion based on a formula to states in 2022, 2023 and 2024 respectively to help states begin establishing the program. Then starting in 2025 and following the next two years, the federal government would pay 90%, 75% and 60% of the cost of operating universal preschool.41 States would need to pay for the remainder of the cost under this plan.

The expansion of child care assistance would occur in two phases. The first phase would occur during the initial three years of the program, paying for an increase in the CCDBG. This increase would allow families up to 75% of SMI (which amounts to $39,221 for a household as of 2019) to place their children in child care without cost, and families above that threshold would pay a sliding scale of up to no more than 7% of their income on child care. The subsidy would be available to families up to 100% SMI the first year, 125% SMI the second year, 150% SMI the third year and 250% thereafter. Half of the increased CCDBG would be required to pay for the new subsidy, and the remaining half set aside for increasing supply, improving quality or further expanding the subsidy.

The second phase would begin in federal fiscal year 2024, when child care would become a shared state-federal entitlement to all families regardless of income, keeping the sliding scale 7% income cap in place for families above 75% SMI. The federal government would pay for 90% of the cost of the subsidy, would reimburse states for the cost of upgrading capacity and quality at the same rate it pays for a state’s Medicaid program (roughly 72% in Kentucky) and would split administrative costs at 50%. This program would run through 2027, at which point it would need to be reauthorized.42 According to Census data from 2019, having a child care subsidy available to families up to 250% SMI would benefit 85% of households with children under 6 years old; and 33% of households with children under 6 are below 75% SMI, meaning they would receive child care at no cost to them.43

These programs would immediately save families a significant amount of money, expand child care capacity for all families with children and improve the pay of the child care workforce to an unprecedented degree. Build Back Better presents an unprecedented opportunity to fix longstanding problems in child care that have held back families, kids and our economy. Congress should enact the law, and Kentucky should immediately begin partnering to implement these transformative improvements.

- Kentucky children are being raised in a number of settings, including biological and adoptive parents, but also by family members, foster parents, legal guardians and other caregiving arrangements. For the purposes of this report, we will simply refer to caregivers of children as parents, recognizing that this term is limited in scope.

- “The Science of Early Childhood Development (InBrief),” Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University, 2007, https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/.

- Taryn Morrissey, “The Effects of Early Care and Education on Children’s Health,” Health Affairs, Apr. 25, 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20190325.519221/full/.

- Cory Curl, “Building Blocks: The Kentucky Early Childhood Cost of Quality Study,” Prichard Committee, November 2017, http://www.prichardcommittee.org/library/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Cost-of-Quality-Brief-November-2017.pdf. Simon Workman, “The True Cost of High-Quality Child Care Across the United States,” Center for American Progress, June 2021, https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2021/07/07075937/True-Cost-of-High-Quality-Child-Care.pdf?_ga=2.25866429.1071006078.1626961972-666485480.1624542688.

- Joanne Rojas and Bethany Davis, “2020 Child Care Market Rate Report,” Child Care Aware of Kentucky, Human Development Institute and the University of Kentucky, Mar. 30, 2021, https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dcbs/dcc/Documents/2020marketrate.pdf.

- 2019 1 year American Community Survey for Kentucky, Accessed Sept. 26, 2021, https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Kentucky%20median%20income&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S1903.

- Assuming 15 hours per semester for two semesters costing $179 per credit hour.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury, “The Economics of Child Care Supply in the United States,” September 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/The-Economics-of-Childcare-Supply-09-14-final.pdf.

- Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages accessed on Sep. 24, 2021.

- “2021 Poverty Guidelines,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, accessed Oct. 6, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references/2021-poverty-guidelines.

- Elise Gould et. al., “A Values-Based Early Care and Education System Would Benefit Children, Parents, and Teachers in Kentucky,” Economic Policy Institute, Jan. 15, 2020, https://www.epi.org/publication/ece-in-the-states/#/Kentucky.

- “The Economics of Child Care Supply in the United States,” September 2021. Barry Kornstein, “Student Loan Debt in the U.S. and Kentucky — Historical Context, Composition of Loans and the Repayment Situation,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Apr. 6, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Student-Loan-Debt-in-the-U.S.-and-Kentucky-1.pdf.

- Jasmine Tucker and Julie Vogtman, “When Hard Work Is Not Enough: Women in Low-Paid Jobs,” National Women’s Law Center, April 2020, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Women-in-Low-Paid-Jobs-report_pp04-FINAL-4.2.pdf. Elise Gould, Marokey Sawo and Asha Banerjee, “Care Workers Are Deeply Undervalued and Underpaid: Estimating Fair and Equitable Wages in the Care Sectors,” Economic Policy Institute, Jul. 16, 2021, https://www.epi.org/blog/care-workers-are-deeply-undervalued-and-underpaid-estimating-fair-and-equitable-wages-in-the-care-sectors/.

- “The Economics of Child Care Supply in the United States,” September 2021.

- Heather Long, “’The Pay Is Absolute Crap’: Child-Care Workers Are Quitting Rapidly, a Red Flag for the Economy,” Washington Post, Sept. 19, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/09/19/childcare-workers-quit/.

- Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages accessed on Sept. 24, 2021.

- Rasheed Malik et. al., “America’s Child Care Deserts in 2018,” Center for American Progress, Dec. 6, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2018/12/06/461643/americas-child-care-deserts-2018/, https://childcaredeserts.org/2018/?state=KY.

- “Child Care in State Economies: 2019 Update,” Committee for Economic Development, 2019, https://www.ced.org/assets/reports/childcareimpact/181104%20CCSE%20Report%20Jan30.pdf.

- KyPolicy analysis of data from “Early Childhood Profile,” Kentucky Center for Statistics, November 2021, https://kystats.ky.gov/Reports/Tableau/2021_ECP.

- Karen Schulman, “On the Precipice: State Child Care Assistance Policies 2020,” National Women’s Law Center, May 2021, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/NWLC-State-Child-Care-Assistance-Policies-2020.pdf.

- Anna Baumann, “Child Care Cuts Part of Broader Underinvestment in Early Learning,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Apr. 8, 2013, https://kypolicy.org/child-care-cuts-part-broader-underinvestment-early-learning/.

- Joseph Lord, “After Cuts, How Many Fewer Children Are Using Kentucky’s Child Care Assistance Program?” WFPL, Sep. 22, 2013, https://wfpl.org/after-cuts-how-many-fewer-children-are-using-kentuckys-child-care-assistance-program/.

- Lowell Ricketts, “Child Care and School Disruptions Continue to Burden Working Parents,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Aug. 9, 2021, https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2021/august/child-care-school-disruptions-burden-working-parents.

- [1] Beth Musgrave, “Restoration of Cuts to Kentucky’s Child Care Assistance Program Delayed,” Lexington Herald Leader, Jun. 20, 2014, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article44494137.html.

- “HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2021,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, accessed on Oct. 5, 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines.

- “Kentucky Child Care Maximum Payment Rate Chart: DCC-300,” Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, October 2021, https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dcbs/dcc/Documents/dcc300kymaxpaymentchart.pdf. “Kentucky’s Commitment to Higher Quality for Early Care and Education,” Kentucky All-STARS, accessed Oct. 5, 2021, https://kentuckyallstars.ky.gov/Documents/KY-All-STARS-7-5.pdf.

- “Kentucky Child Care Maximum Payment Rate Chart: DCC-300,” Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services.

- 922 Kentucky Administrative Regulation 2:160, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/kar/922/002/160reg.pdf.

- Data from an open records request to the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services received on Sept. 20, 2021 and from the 2019 1 year estimates of the American Community Survey.

- Data from an open records request to the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services received on Sept. 20, 2021.

- Sarah Shaw, Anne Partika and Kathryn Tout, “Child Care Subsidy Stability Literature Review,” Child Care and Early Education Policy and Research Analysis, February 2019, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/cceepra_subsidy_stability_literature_review_508_final.pdf.

- “Child Care in State Economies: 2019 Update,” Committee for Economic Development.

- Nicole Bateman and Martha Ross “Why Has COVID-19 Been Especially Harmful for Working Women?” Brookings, October 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/essay/why-has-covid-19-been-especially-harmful-for-working-women/.Olivia Lofton et. al., “Parental Participation in a Pandemic Labor Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Apr. 5, 2021, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2021/april/parental-participation-in-pandemic-labor-market/. Alexander Monge Naranjo, Qiuhan Sun, “Women Affected Most by COVID-19 Disruptions in the Labor Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/first-quarter-2021/women-affected-most-covid-19-disruptions-labor-market.

- Kentucky Department for Community Based Services, “Block Grant Program Status Report,” Aug. 6, 2020, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/7/12829/Aug%2026%202020%20block_grant_CCDF_Status_Report_Jan_June_2020.docx.pdf.

- Office of Governor Andy Beshear, “Gov. Beshear Provides Update on COVID-19,” Oct. 7, 2020, https://chfs.ky.gov/News/Documents/nrcaresact.pdf.

- Alycia Hardy and Katherine Gallagher Robbins, “Child Care Relief Funding in the Year-End Stimulus Deal: A State-by-State Estimate,” The Center for Law and Social Policy, Dec. 22, 2020, https://www.clasp.org/publications/fact-sheet/covid-relief-stimulus-child-care-state-estimates.

- Bobbi McSwine, “Kentucky Lays Out Plan for Child Care Funding,” WTVQ, Feb. 3, 2021, https://www.wtvq.com/2021/02/03/kentucky-lay-out-plan-for-child-care-funding/.

- Sarah Vanover, “American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) Funding for Child Care,” Division of Child Care, presented to the Interim Joint Budget Review Subcommittee on Human Resources on Aug. 4, 2021, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/12/13397/Aug%204%202021%20Vanover%20ARPA%20Funding%20PowerPoint.pdf.

- Sarah Vanover’s presentation to the ThriveKY quarterly forum with the Cabinet for Health and Family Services on Nov. 2, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AoZa5yfcmrQ.

- Sarah Vanover, “American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) Funding for Child Care,” Aug. 4, 2021.

- Legislative text of H.R. 5376 accessed on Nov. 9, 2021, https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR5376RH-RCP117-18.pdf.

- Legislative text of H.R. 5376 accessed on Nov. 9, 2021, https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR5376RH-RCP117-18.pdf.

- KyPolicy analysis of data from the 2019 American Community Survey 1 year estimates.