To view this brief in PDF form, click here.

Kentucky loses an estimated $25 million a year because state lawmakers haven’t yet taken steps to recoup lost revenue from federal estate tax changes that essentially eliminated the state’s estate tax in the 2000s 1. Recognizing estate taxes generate revenue and make taxes fairer, many states have either decoupled from the federal changes or enacted their own, separate estate taxes.

Legislation to sever the connection between Kentucky’s estate tax and federal law has been proposed. For instance, during the 2015 legislative session House Bill 132 called for Kentucky to collect estate taxes “under the federal tax law as it was in effect on January 1, 2003,” prior to the repeal of the federal estate tax credit for states.

Restoring Kentucky’s estate tax — a move that would affect only the largest, wealthiest estates — would generate needed resources for state priorities like public education and health that benefit all Kentuckians. Asking a little more of those who can best afford to pay and who receive many of the biggest breaks from Kentucky’s tax code would also push back against the way our state and local taxes make income inequality worse overall.

Taxes on Inherited Wealth Perform Important Functions

Estate taxes have several purposes: to generate revenue for public investments, provide a backstop to income tax losses through unrealized capital gains and address the concentration of wealth that threatens widespread prosperity and broad economic growth.

The federal estate tax is applied to the value of large transfers of money and property made from one generation to the next 2. With inequality at levels not seen in this country in almost 100 years, an estate tax is especially important today. It is an avenue for those who have profited above all others from public investments in the economy to pay their fair share toward the good schools, health care and other services that are necessary for new generations of hard-working people to achieve the American dream.

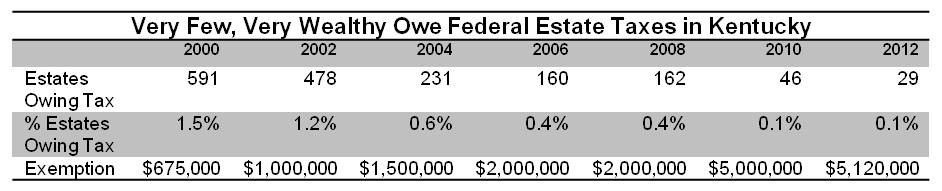

Structurally, the estate tax is applied to the market value, at the time of death or up to six months later, of such assets as real estate, trusts, cash, stocks, bonds, businesses, pensions, life insurance policies and the value of taxable gifts made over one’s lifetime. Once exemptions and deductions for transfers between spouses, gifts to charitable organizations, debts and administrative costs are accounted for, only the very wealthiest Americans owe federal estate taxes 3. In fact, the nationwide share of estates subject to the tax was at an historical low of 0.15 percent in 2012, the most recent year for which data are available. The share of Kentuckians owing federal estate taxes was even lower — just 0.1 percent of all the state’s estates (see table below). As federal law stands today, the first $5.43 million of an estate is totally exempt from the tax and that number is adjusted each year for inflation.

Source: Citizens for Tax Justice

Most states levied estate and inheritance taxes prior to establishment of the federal estate tax in 1916. Kentucky’s inheritance tax, for example, was enacted in 1906. These taxes on the very wealthy helped in a small way to counterbalance states’ heavy reliance on “regressive” sales taxes — meaning the lower a family’s income, the larger share of it they pay in sales taxes.

In order to provide for more uniform estate taxation by states, a state credit against the federal tax for state estate and inheritance taxes was added to the federal estate tax in 1926 4. Under the law, states that levied an estate tax equal to the amount of the credit did not increase the total (federal and state) tax bill. Rather, states picked up a share of federal estate tax collections, as Kentucky began doing in 1926 5. When the credit was phased out in 2005 under the 2001 federal tax cuts and replaced with a deduction, states lost the ability to automatically pick up a portion of federal estate tax liability and many were left with no estate taxation at all. In 2012, the repeal of the credit was made permanent.

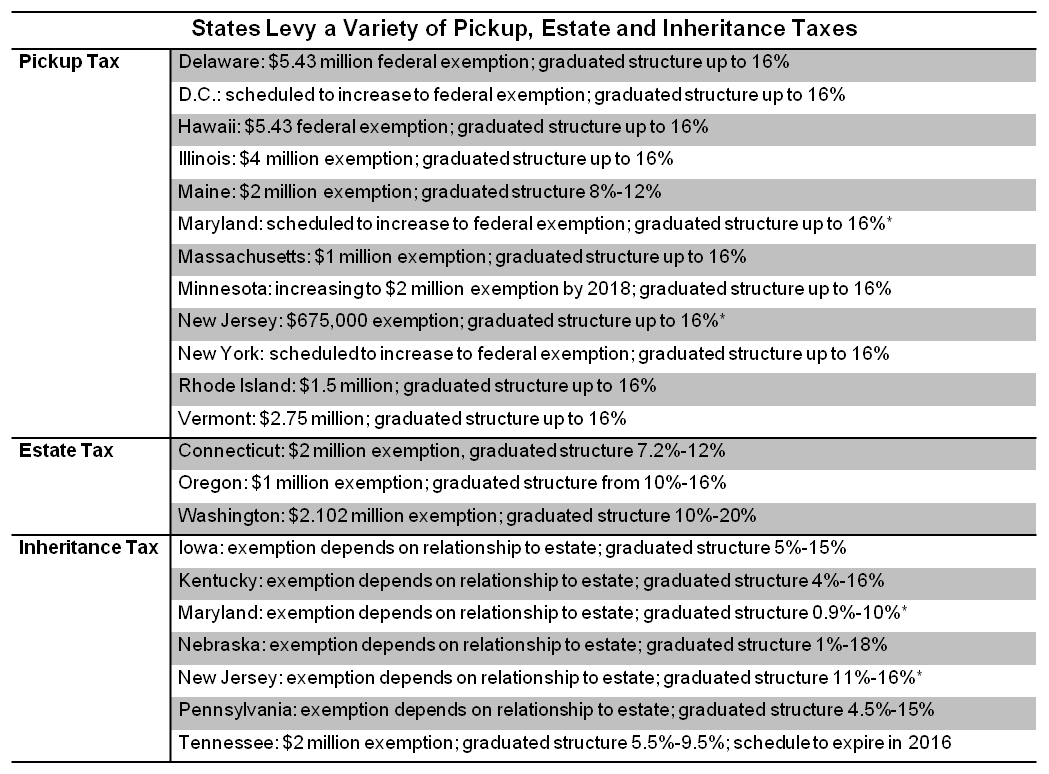

Since then, three states have established their own estate taxes separate from the federal tax and 11 states and the District of Columbia have “decoupled” from the repeal of the state credit, allowing them to keep an estate tax that is the same or similar to the prior tax 6.

Kentucky currently does not have an estate tax, but has retained its other tax on the generational transfer of wealth — the inheritance tax. Distinct from the estate tax which is paid on the net value of the taxable estate, inheritance taxes are assessed against the value received by each beneficiary, with exemptions based on one’s relationship to the estate. Spouses, parents, children, grandchildren and siblings became completely exempt from the inheritance tax in 1998 7. Beforehand, they were entitled to exemptions ranging from $5,000 to $20,000 and paid from two percent on inheritances valued up to $20,000 to ten percent on inheritances exceeding $500,000. More distant relatives still pay from four percent on inheritances valued at less than $10,000 to 16 percent on those with value exceeding $60,000, with exemptions ranging from $500 to $1,000 8.

Before the federal pickup credit was repealed, Kentucky’s estate taxes were equal to the difference between the inheritance tax and the federal estate tax credit 9. In other words, the amount someone paid in inheritance taxes reduced the amount he or she paid in state estate taxes.

Estate and Inheritance Tax Erosion Means Less Revenue, Raised Less Equitably

Today the inheritance tax in Kentucky is a small but important source of General Fund revenue, generating $51 million in 2015 10. To put that amount into context, Kentucky budgeted $48 million General Fund dollars in 2015 for its child care assistance program which helps low-income, working families pay for child care 11.

Yet in the past, taxes on inherited wealth have provided more resources for investments in education, health and other areas that help create and support the middle class. Accounting for inflation, Kentucky estate and inheritance taxes shrunk 59 percent between 2001 and 2014 12. Along with the elimination of the estate tax, an enhanced exemption from the inheritance tax for siblings in 1995 and the phase-out of inheritance taxes on close relatives by 1998 have reduced collections.

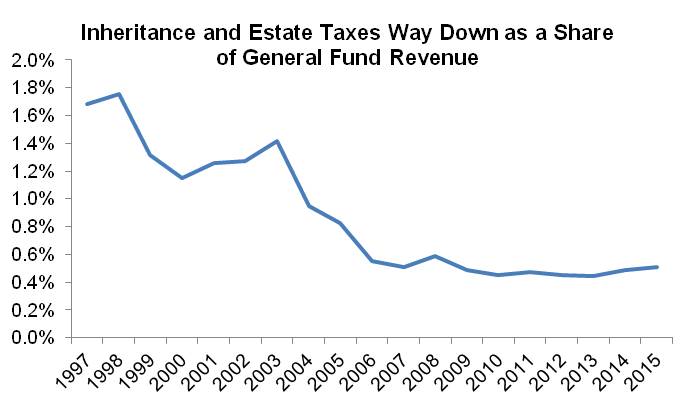

Since the late 1990s, inheritance and estate taxes have declined and flattened as a share of General Fund revenue (see below). If these taxes generated the same share of state revenue they did in 1997, Kentucky would have collected $168 million in 2015, compared to $51 million in actual receipts — a much-needed $117 million difference to help address public needs.

Source: KCEP analysis of June Monthly Tax Receipts Reports, Office of the State Budget Director

The loss in state revenue resulting from changes to estate and inheritance taxes can be dealt with in two ways. The money can be made up on the spending side by reducing investments in important public services and other fiscal maneuvering and on the revenue side by raising taxes that fall less heavily on the wealthiest households. Both are used in practice.

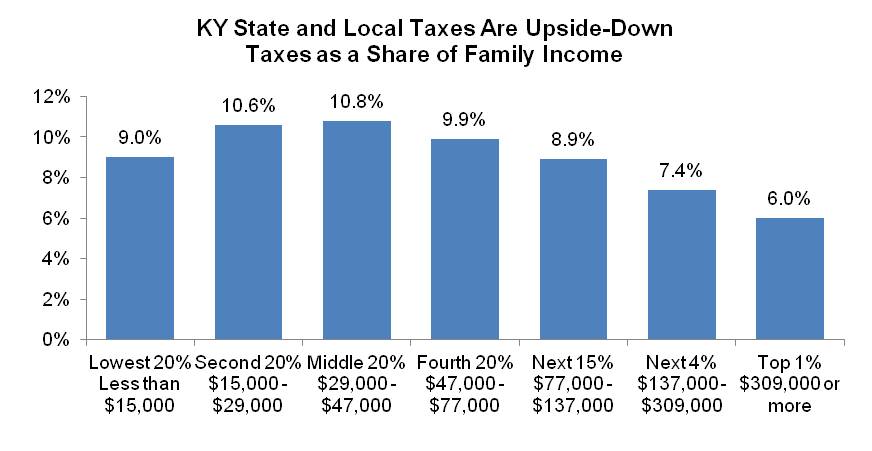

Today in Kentucky, low-income and middle class families pay a larger share of their income in state and local taxes than the wealthiest do, as shown in the graph below. For example, Kentuckians whose average annual income is $23,000 pay 10.6 percent of family income in taxes, while those averaging $839,500 a year or more – the top 1 percent — pay just 6.0 percent 13. That means, on average, the wealthiest Kentuckians are bringing home 37 times more income but paying just over half, percentagewise, what low-income residents do in state and local taxes 14. Restoring the estate tax would help offset that unfairness.

Source: Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy

Inequality is a Growing Problem in Kentucky, One that Estate Taxes Can Help Address

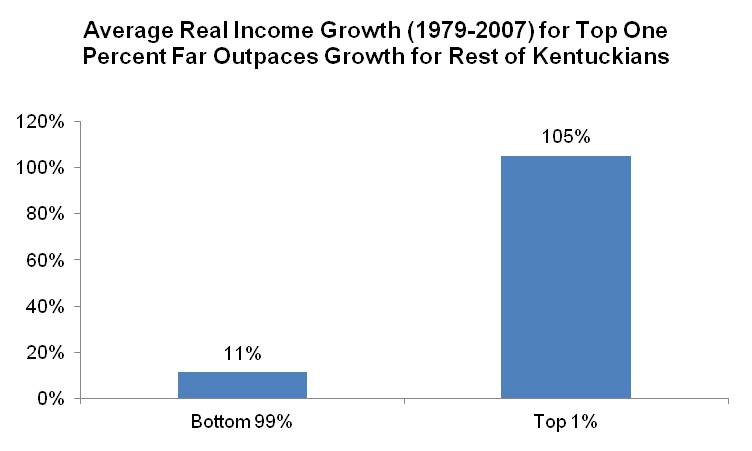

A tax system where the wealthiest people pay the lowest percentage of their income in taxes could be described as upside-down. This has serious implications. As more and more struggle to make ends meet while a relatively tiny sliver of the population sees its income grow dramatically (as the graph below shows), the imbalance threatens our state budget as well as economic growth.

In the three decades leading up to the Great Recession, those whose income put them in the top one percent of all Kentuckians took home nearly half of state income growth. In 2011, the top one percent made 17 times as much as everyone else15. With such a disproportionate share of growth in the economy going to the wealthiest, it would be a common-sense policy decision to make it so that taxes paid by those at the top on inherited wealth should at least keep pace with economic growth. But in Kentucky these taxes have decreased as a share of personal income to 0.03 percent, down from about 0.1 percent where they hovered from the late 1970s through the 1990s 16.

Source: EARN Analysis of state-level IRS data, Piketty and Saez 2012

With inequality rising to levels not seen since the Great Depression, it’s important that states and the federal government recommit to addressing the concentration of wealth in the hands of a relative few. A growing body of research explores and explains how increasing inequality hurts the economy, including by decreasing educational opportunities and income mobility 17. Another major concern is that with the financial means to influence policy comes the power to keep dollars flowing in the direction that benefits those interests.

Many state and federal policies are needed to address inequality, including tax reform that calls upon those at the very top to pay their fair share toward investments in a stronger economy 18. Federal estate tax exemptions have skyrocketed to $5.43 million per spouse today from around $600,000 in the 1990s. Today, fewer than two of every 1,000 estates owe any estate tax 19. Furthermore, with exemption rates tied to inflation, wealthy estates get protection even as the minimum wage and other supports for average working people erode 20.

Common Arguments against Estate Taxes Are Unfounded

Those who support maintaining or even expanding this special treatment for the ultra-wealthy make the unsubstantiated claim that estate taxes force family farms and small businesses to liquidate assets. There are many reasons this is an extremely rare occurrence. To begin with, high exemptions mean that very few farms and businesses even file estate taxes. In 2012, just one tenth of one percent of Kentucky estates (29, total) owed even a dollar in federal estate taxes 21. The likelihood that federal estate taxes affect these inheritors is further reduced by laws allowing family farms to be assessed at their agricultural rather than “best use” market value and a “qualified family-owned business-interest deduction.” 22 In rare cases where estate taxes are owed, another federal provision allows many businesses to spread payments over 15 years.

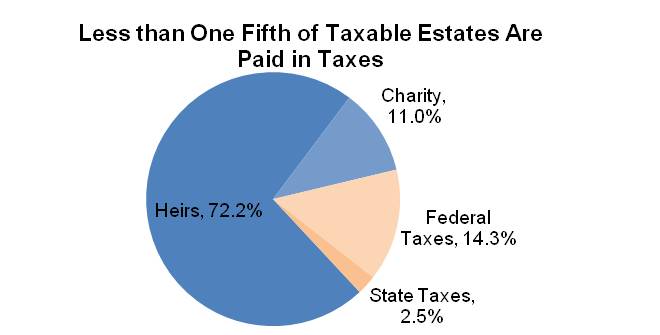

The fact is that the large majority of estates’ wealth goes to the intended beneficiaries — not taxes. For the 0.1 percent of taxable estates that owed any estate tax in the U.S. in 2011, more than 80 cents of every dollar went to heirs and charities.

Source: Citizens for Tax Justice analysis of IRS data on taxable estates of Americans who died in 2011.

Another anecdotal argument in favor of special treatment for transferred wealth is that estate taxes cause residents to leave states that have them. In reality though, fewer than two out of every 100 Americans move from one state to another each year and when they do the most common reasons are for a job, family considerations, weather and lower housing costs — not taxes 23. Related more specifically to the myth that higher taxes cause the wealthy to flee, under that logic, states with comparatively high income taxes should see big population losses as well. But actual practices show otherwise. For instance, from 2005 to 2011, California – a state with relatively high state income taxes – saw more people with incomes greater than $200,000 a year move into the state than move out 24. Even stronger evidence against the tax-flight myth comes from New Jersey, which increased its top income tax rate in 2004 by 2.6 percentage points to 8.97 percent — one of the highest rates in the nation. Because it affected households with taxable income greater than $500,000, the impact of this tax increase serves as a good proxy for estate taxes since they also affect only the very wealthy. Statistical analysis of trends after New Jersey’s tax increase confirm that rich people have the same “non-response” to state tax changes as the general population. 25

Kentucky Should Restore the Estate Tax

Following lawmakers in 11 other states and the District of Columbia, the General Assembly can restore Kentucky’s estate tax by referencing a date in the statutes prior to the federal repeal of the pickup tax credit for states. Rep. Jim Wayne’s 2015 bill proposed linking it to “federal tax law as it was in effect on January 1, 2003, and without any of the scheduled increases” that took effect under the 2001 federal tax cuts. In 2003, the exemption rate was set at $1 million, meaning estates smaller than $1 million were exempt as well as the first million of estates larger than the threshold. At full implementation, the bill would have generated an estimated additional $25 million for the state’s General Fund.

To reduce any impact on family businesses, Kentucky could piggyback on the previously mentioned federal law that provides an additional exemption on top of the standard amount. Kentucky already assesses inherited farm land at its agricultural value and allows taxes to be paid in up to ten annual installments if the net amount exceeds $5,000 26.

States that base their estate tax on the previous federal credit have a maximum state estate tax rate of 16 percent and can either tie their exemption to the current federal level ($5.43 million per spouse) or create their own lower exemption. Alternatively, three states have separate estate taxes not tied to the federal pick up tax. A new state tax would be partially offset because it would be deductible from federal estate taxes.

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy

*Maryland and New Jersey levy a pickup tax and a separate inheritance tax.

Conclusion

Kentuckians are rightly concerned about the struggles of everyday working people at a time when the wealthiest few are enjoying more and more of today’s economic growth. A tax system that fails to generate enough resources to meet growing needs at the same time it gives big breaks to those who arguably need them the least only makes the situation worse. Restoring Kentucky’s estate tax would be an important step in the right direction.

- Representative Jim Wayne, “House Bill 132,” Kentucky General Assembly, 2015, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/15RS/HB132.htm. John Scott, “Issues Confronting the 2012 Kentucky General Assembly: Estate Taxes,” Legislative Research Commission, November, 2011, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/lrcpubs/IB236.pdf. ↩

- Joseph Cordes, Robert Ebel and Jane Gravelle, “The Encyclopedia of Taxation and Tax Policy, Second Edition,” The Urban Institute Press, 2005. ↩

- Steve Wamhoff, “State-by-state Estate Tax Figures Show Why Congress Should Enact Senator Sanders’ Responsible Estate Tax Act,” Citizens for Tax Justice, September 22, 2014, http://ctj.org/pdf/estatetax2014.pdf. ↩

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), “State Estate and Inheritance Taxes,” July 2014, http://www.itep.org/pdf/estatetax2014.pdf. ↩

- Jeffrey Cooper, “Interstate Competition and State Death Taxes: A Modern Crisis in Historical Perspective,” Pepperdine Law Review 33 (4), 2006, http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1219&context=plr. ↩

- ITEP, “State Estate and Inheritance Taxes.” The current total of states with a separate pickup tax is 11, as North Carolina eliminated the tax in 2013. Three additional states have enacted their own estate taxes. ↩

- Governor’s Office for Economic Analysis, “Tax Expenditure Analysis: 2014-2016,”April 30, 2014, http://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Documents/Special%20Reports/Tax%20Expenditure%20Analysis%20Fiscal%20Years%202014-2016.pdf. ↩

- Kentucky Revised Statutes (KRS) 140.070, “Inheritance Tax Rates,” http://www.lrc.ky.gov/Statutes/statute.aspx?id=28983 ↩

- The credit was replaced with a deduction, meaning that taxpayers may deduct any state-level estate taxes paid from the value of their estate for federal estate tax purposes, therefore receiving a partial reduction in net taxes paid equal to the value of the state taxes paid times the federal tax rate. ITEP, “State Estate and Inheritance Taxes.” ↩

- Office of the State Budget Director, “Monthly Tax Receipts; June 2015,” http://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Tax%20Receipt%20Reports%20%20Fiscal%20Year%202015/1506TaxReceipt.pdf. The State Budget Director estimates that inheritance tax exemptions will reduce collections by $55 million in 2016. Furthermore, the five percent discount applied to the tax if it is paid in full within nine months after death, and the exemption for gifts made to “educational, religious, charitable or certain governmental organizations”—will further reduce inheritance tax collections by about $1 million and $12 million in 2016, respectively. Governor’s Office for Economic Analysis, “Tax Expenditure Analysis: 2014-2016.” ↩

- Office of the State Budget Director, Budget of the Commonwealth, 2014-2016. http://osbd.ky.gov/Documents/Most%20Recent%20Publications/Operating%20Budget%20-%20Volume%20I%20%28Full%20Version%29.pdf. ↩

- Office of the State Budget Director, “Monthly Tax Receipts Reports.” ↩

- ITEP, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” Fourth Edition, January 2013, http://www.itep.org/pdf/whopaysreport.pdf. ↩

- Kentucky adheres to other federal laws that shelter transferred wealth from taxation—or in other words, which give preferential tax treatment to very wealthy families: when an asset that has appreciated in value is given as a gift during a donor’s lifetime, the capital gains are not taxed, a practice will cost Kentucky about $14 million in the budget year 2016. When property that has appreciated in value is transferred at a donor’s death, the recipients value “basis” is the current market value, meaning that the capital gains will never be taxed. Kentucky will lose an estimated $81 million in this budget year 2016 to this practice. The federal government recoups some of this loss through the estate tax but Kentucky does not have an estate tax. Governor’s Office for Economic Analysis, “Tax Expenditure Analysis: 2014-2016.” ↩

- Estelle Sommeiller and Mark Price, “The Increasingly Unequal States of America; Income Inequality by State, 1917 to 2011,” Economic Analysis and Research Network (EARN), February 19, 2014, http://s2.epi.org/files/2014/Income-Inequality-by-State-Final.pdf. ↩

- Author’s analysis of data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, The Office of the State Budget Director and the State and Local Government Finance Data Query System. ↩

- Jared Bernstein, “The Impact of Inequality on Growth,” December 2013, The Center for American Progress, http://cdn.americanprogress.org//www/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/BerensteinInequality.pdf. Jonathan D. Ostry, Andrew Berg and Charalambos Tsangarides, “Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth,” IMF Staff Discussion Note, International Monetary Fund, February 2014, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2014/sdn1402.pdf. Joe Maguire, “How Increasing Income Inequality is Dampening U.S. Economic Growth, And Possible Was to Change the Tide,” Standard and Poor Global Credit Portal, August 6, 2014, https://www.globalcreditportal.com/ratingsdirect/renderArticle.do?articleId=1351366&SctArtId=255732&from=CM&nsl_code=LIME&sourceObjectId=8741033&sourceRevId=1&fee_ind=N&exp_date=20240804-19:41:13#ContactInfo. ↩

- Senator Bernie Sanders has proposed the “Responsible Estate Tax Act” which would reduce the exemption to its level in 2009, $3.5 million per spouse, have a graduated rate structure from 40 to 55 percent, and result in about 0.3 percent of estates being liable. President Obama has also recommended reinstating the 2009 exemption, but his plan proposes a flat rate of 45 percent. Steve Wamhoff, “State-by-State Estate Tax Figures Show Why Congress Should Enact Senator Sanders’ Responsible Estate Tax Act.” ↩

- ITEP, “State Estate and Inheritance Taxes.” ↩

- Robert Greenstein from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities points out that at the same time as estate tax changes benefitting millionaires were made permanent in 2013 fiscal cliff negotiations, 2009 improvements to the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit were scheduled to expire in 2017. “Disparate Treatment: Permanent, Million-Dollar Estate-Tax Breaks for Wealthy Heirs vs Temporary Tax Credit Improvements for Low-Income Working Families,” January 4, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/disparate-treatment-permanent-million-dollar-estate-tax-breaks-for-wealthy-heirs-vs-temporary-tax-credit-improvements-for-low-income-working-families/. ↩

- Steve Wamhoff, “State-by-state Estate Tax Figures Show Why Congress Should Enact Senator Sanders’ Responsible Estate Tax Act.” ↩

- Congressional Budget Office, “Effects of the Federal Estate Tax on Farms and Small Businesses,” July 2005, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/65xx/doc6512/07-06-estatetax.pdf. Based on federal estate tax returns for 2000, the CBO found that, nationwide, if the exemption rate for that year had been set at $3.5 million, all but 41 family-owned businesses and 13 family farms would have had the liquid assets necessary to pay their estate taxes. At the current and inflation-indexed exemption of $5.43 million, the numbers are likely to be smaller still. ↩

- Robert Tannenwald, Jon Shure and Nicholas Johnson, “Tax Flight is a Myth: Higher State Taxes Bring More Revenue, Not More Migration,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 4, 2011, http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3556. ↩

- Michael Mazerov, “State Taxes Have a Negligible Impact on Americans’ Interstate Moves,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 21, 2014, http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=4141. ↩

- Cristobal Young and Charles Varner, “Millionaire Migration and State Taxation of Top Incomes: Evidence from a Natural Experiment,” National Tax Journal, June 2011, 64(2), http://web.stanford.edu/~cy10/public/Millionaire_Migration.pdf. ↩

- KRS 140.310, KRS 140.222 http://www.lrc.ky.gov/statutes/chapter.aspx?id=37672. ↩