Because of the recession and subsequent shortfalls in the state’s annual contributions to the Kentucky Teachers’ Retirement System (KTRS), the system’s liability is growing and the problem is becoming more severe each year. Now, KTRS has only 52 percent of the resources it needs to pay future benefits.

A proposal from KTRS would take advantage of the current low interest rates to refinance a portion of the debt the state owes to Kentucky’s teachers. The refinancing would take the form of a bond, and in the current context is a sensible next step as long as it’s part of a financial plan that commits the state to begin making full payments to the system in the near future.

Digging out of a hole

By law, Kentucky makes annual contributions in its budget for the retirement benefits earned by its teachers that year and to make up any shortfall from previous contributions. But in 2009, as the economy fell into recession and the financial returns of the retirement system dropped along with the markets, the state stopped making full payments to the system.

In the first year, that amounted to a payment shortfall of $60 million, but the amount grew in the following years as the full effect of the recession was felt and the impact of the state’s annual funding shortfalls compounded. In April, the General Assembly passed a budget in which the contribution for 2016 is $487 million short of what’s needed to avoid insolvency down the road, or a shortfall of nearly five percent of the state’s General Fund budget.

Additional dollars must be found to pay down the liability, as these benefits are earned by and legally owed to Kentucky’s teachers and the problem gets worse the longer we wait. Teachers do not participate in Social Security, meaning their pensions are critical to economic security in retirement. And the $2 billion paid out each year in benefits plays a significant role in Kentucky’s economy.

While finding the revenue to begin making full payments is the most important problem to be solved, a bond to refinance a portion of the debt is reasonable given the financial markets. The wisdom of such a bond depends on timing. For it to work, the expected rate of return on the investments that are made with the bond proceeds must exceed the interest rate paid on the bonds. That means it needs to be issued at a time when interest rates are low and financial markets are not overvalued.

Interest rates are certainly at historic lows for the time being, so that’s to the state’s advantage (KTRS suggests a bond could likely be sold with an interest rate of less than five percent). While no one can predict the future performance of financial markets, the ratio of stock prices to underlying corporate earnings—while having increased recently to above its historic average—is nowhere near where it was during the dot-com market bubble of the early 2000s and the bubble that preceded the Great Recession. Also, the past financial performance of KTRS is good, meeting or exceeding its 7.5 percent assumed rate of return over the long term.

A recent report by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College shows that from the vantage point of 2014 the experience of most bonds issued for pension obligations over the last couple of decades is positive with the exception of those issued at the end of the peak financial markets in the late 1990s and right before the crash in 2007. While the authors note that there is risk involved, they also say that bonds “could potentially be a useful tool under the right circumstances.”

Issuing a bond does two things. First, it can lower the long-term costs of paying off the debt because of the difference between what the system earns with the funds and the cost of the bond. Second, by providing an infusion of cash to the system it gives the state a little time to figure out a plan for addressing the most important part of what needs to happen—a way to come up with the funds to make the annual payments on the liability over the next few decades.

The pieces of a plan

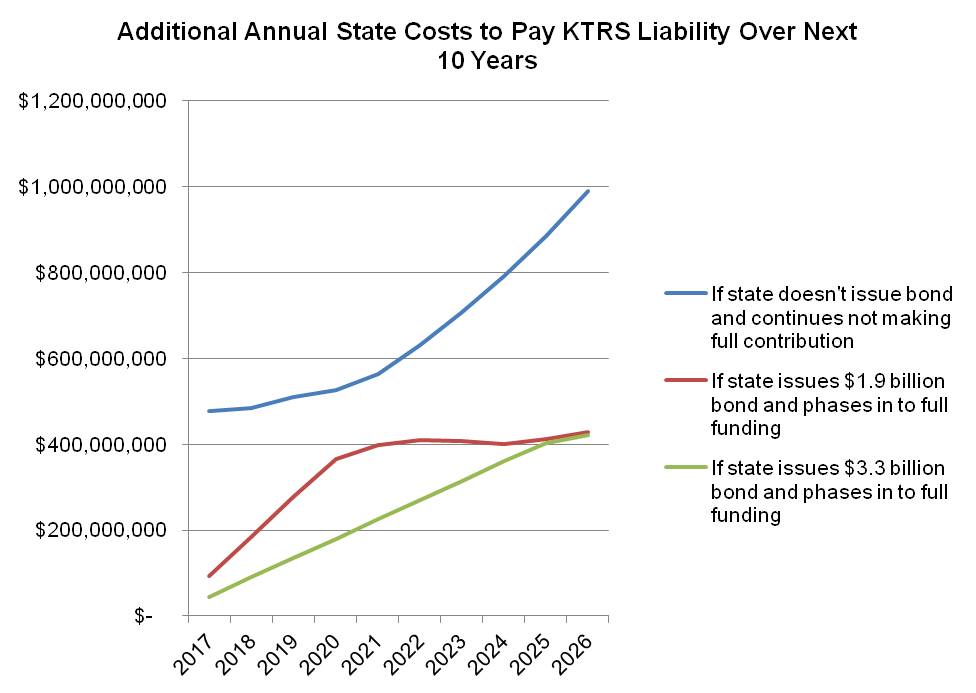

KTRS lays out two options in its proposal, a $1.9 billion bond and a $3.3 billion bond. KTRS shows how the state can repurpose funds already built into the state budget for KTRS to help pay for the bonds in the future—monies that go for past cost-of-living adjustments and sick leave liability. Also, they note that as prior bonds are paid off the payments can be redirected to help with costs.

With the smaller bond, the state would have four years to come up with the funds to make the full annual contribution to KTRS of about $400 million annually. An essential part of KTRS’ plan is that they propose the state immediately start ramping up its contributions to the system in the next budget beginning with $92 million in 2017, $184 million in 2018, $276 million in 2019 and $366 million in 2020. With the larger bond, it would take seven years for the state to reach the full $400 million annual contribution amount with the payments ramping up by $45 million each year.

Not issuing a bond and continuing to avoid making the full required payment to KTRS will cause the problem to grow. By 2026, according to KTRS, the state would be short $988 million a year in payments compared to about $420 million a year if it issues the bonds and phases in to making the full annual contribution to KTRS (see graph).

Source: Kentucky Teachers’ Retirement System presentation to Interim Joint Committee on State Government.

Because of a tight state budget and the loophole-ridden tax system, making the full contributions in the future must be part of a broader revenue conversation that the state needs to be having as soon as possible. But in the meantime, Kentucky should take advantage of low interest rates to refinance the pension liability and somewhat reduce the payments in the future, while making sure to include a commitment to phasing in full annual payments to the system. While it’s not all that will need to happen, it’s a prudent next step.