During the 2021 Kentucky General Assembly — as public school advocates were prevented from being in the Capitol by the COVID pandemic — lawmakers passed legislation to fund private schools for the first time. In October 2021, the Franklin Circuit Court ruled aspects of the new voucher law unconstitutional, and the program has been suspended pending the outcome of the litigation.

Last week, new bills were filed to further expand this private school voucher program by making it permanent, doubling or quadrupling its cost and opening it up to even more higher-income families. This year’s proposals attempt to address one aspect of the bill declared unconstitutional by the court by making private school tuition an eligible program expense in all counties instead of just the 9 counties authorized by 2021’s House Bill 563 (HB 563). But these proposals remain fundamentally at odds with the state’s constitutional mandate to provide for an efficient system of common schools and prohibition against public spending on private education. At a time when resources are badly needed for public education in Kentucky, 2022 Senate Bill 50 (SB 50) and House Bill 305 (HB 305) would hand over to unaccountable private entities control of an even larger pot of monies than was provided under HB 563.

Here are ways these bills would make an unconstitutional program more expensive and inequitable.

More public funds diverted to unaccountable private entities, creating a bigger, permanent hole in the General Fund

Last year’s HB 563 diverted up to $25 million annually at full implementation from the General Fund to private entities. Instead of paying their taxes to flow through the Budget of the Commonwealth to investments in education, human services and other budget areas, people who divert funds to private educational entities called “Account Granting Organizations” (AGOs) under HB 563 receive an incredibly rich income tax break up to 100% of what they fund and even surpassing that amount in certain circumstances. While the state constitution prohibits direct appropriations for private education, “neo-voucher” programs like HB 563 skirt around that prohibition by spending through tax giveaways.

The $25 million price tag on HB 563’s tax expenditure was not insubstantial, especially in the context of inadequate funding for public education. Recently, the House proposed a new biennial budget without any additional funding for preschool, extended school services or mandated teacher raises. The House budget’s modest overall dedication of resources to public education is at a time of historic opportunity, due to a large surplus, to begin reinvesting in deeply cut public services.

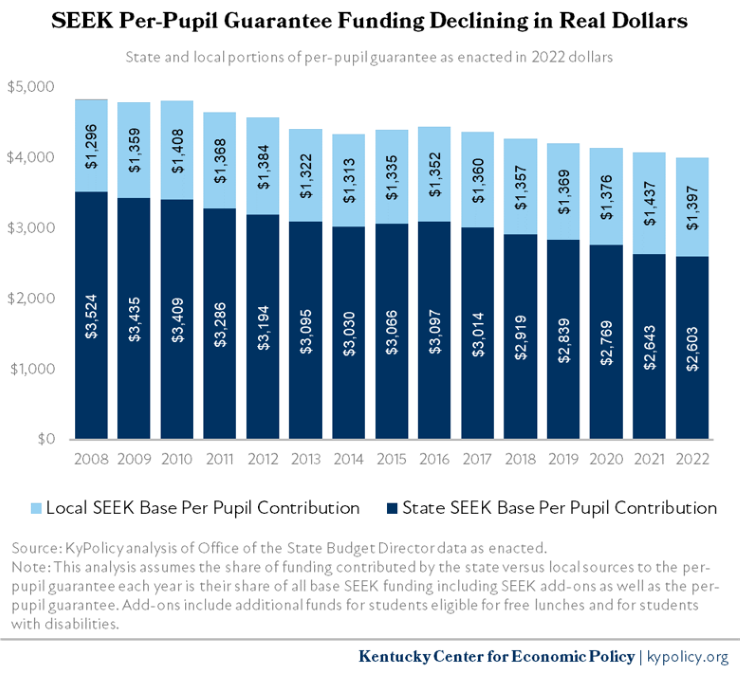

This year’s voucher bills would divert even greater resources to private schools. SB 50 would allow the annual program cap to grow to $50 million, and the House version to $100 million. Adding more harm, the proposals would end HB 563’s 5-year sunset, meaning instead of having to reauthorize spending on private schools after 2026, this year’s bills would give even greater spending on private schools permanent priority over public school funding. These increased expenditures for private schools must be understood in the context of historic state disinvestment in public schools. Among other reduced education funding streams, the legislature has allowed its base guaranteed SEEK funding to erode over the last decade, with the state currently contributing $921 less per student than it did in 2008 once adjusted for inflation.

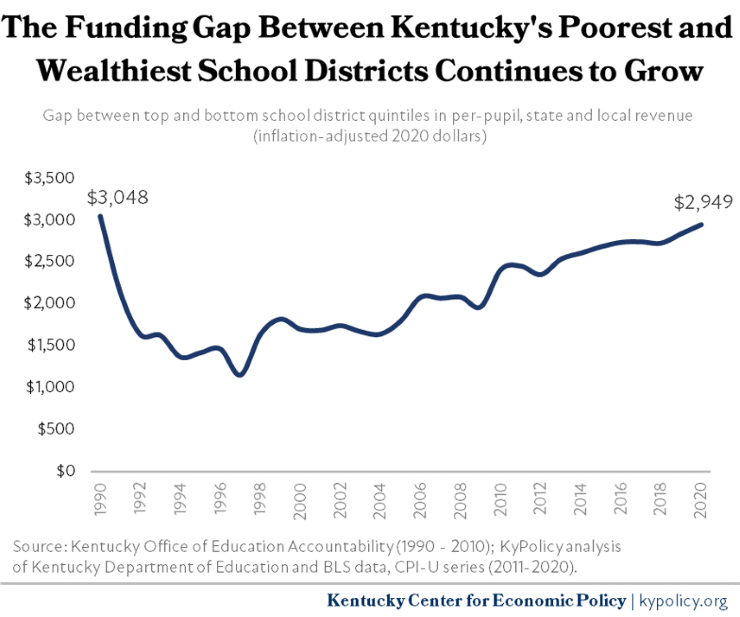

By devoting fewer state dollars to public education, Kentucky has shifted reliance for funding education from the state to local districts. Because districts vary in wealth, and therefore in their ability to raise local revenue, the gap in total state and local revenue per-pupil is widening between districts and nearing the level declared unconstitutional by the Kentucky Supreme Court prior to the passage of the Kentucky Education Reform Act (KERA). Less state funding for public education will continue to cause this gap between wealthy and poor districts to grow, further harming the state’s duty to provide a quality education regardless of where a child lives.

Voucher proponents’ claims that private school funding programs serve communities with the greatest need must be understood in the context of what research says about how to improve equity in education. In its early years, KERA’s equalizing funding formula, SEEK, provided a large infusion of additional resources, especially in districts with less capacity to raise revenue because of lower property tax bases, demonstrably improving outcomes for students in these communities. Public education programs and services providing special support for disadvantaged students — such as Family Resource and Youth Service Centers and extra payments for students from low-income families and students for whom English is a second language — also ensure state resources go to students and schools with greater needs. Conversely, research suggests that contemporary voucher programs can worsen racial and socioeconomic stratification.

Further, vouchers divert public resources to private entities that do not share public schools’ mandate to serve all students and to protect them from discrimination based on race, religion, ethnicity, LGBTQ status, disability or location, for example. Kentucky’s voucher program awards tax dollars to private education service providers while shielding them from state and local oversight and authority.

Diverted funds available to more affluent families

Why do voucher programs tend to exacerbate inequalities? Not only do they take resources out of state coffers that would otherwise flow through public investments benefiting everyone — and in the case of education spending, that are weighted for equity — but the design of these programs also often allows relatively affluent families to receive state dollars to send their children to private schools.

Under 2021 HB 563’s generous income eligibility threshold for participating students, families with incomes up to 175% of the threshold for federal reduced price meals could acquire diverted public funds for their students’ education. Though voucher advocates have long described these programs as targeted to families who cannot afford private schools, research shows that the most affluent families eligible for these kinds of programs tend to benefit from them, including families who are already paying for private school out of pocket.

That’s because families with means face the fewest barriers to applying for, complying with and participating in these programs. Parents in rural communities with access to fewer private schools, those who work two or more jobs, and parents with limited transportation and internet access face more barriers.

This year’s HB 305 and SB 50 would exacerbate the existing inequities in HB 563 by increasing the income eligibility threshold even further, allowing even better-off families to qualify. SB 50 would increase the threshold to 200% of reduced price meal eligibility, making 70% of Kentucky children eligible to receive diverted public resources for private schooling. And at 250% of reduced price meal eligibility, or $121,175 in annual income for a family of 4, HB 305 would make 77% of Kentucky kids eligible to participate — a far cry from focusing on children and families who truly cannot afford private school tuition.

More power and profits to wealthy donors

By increasing the program cap from $25 million to $50 million or $100 million, this year’s voucher proposals would also increase the pot of monies from which holders of marketable securities can profit.

As set up by HB 563 and maintained in this year’s bills, all donors to private educational entities in Kentucky can recoup between 97% and 100% of their donation — a tax break 19 times bigger than the state’s charitable deduction for other kinds of giving to nonprofits such as places of worship, veterans associations, animal shelters and food banks. Essentially, these programs allow special interests to divert what would otherwise be tax payments on a dollar for dollar basis from the state General Fund, where appropriations are made by the publicly elected General Assembly, to private entities and individuals who are not accountable to the people of Kentucky — a privilege granted to no other special interests.

Under the Kentucky constitution, the General Assembly is vested with the sole authority to appropriate funds. Yet the way this program is set up, the General Assembly relinquishes its power and authority to appropriate funds to private entities and individuals for the purpose of accomplishing a goal it cannot accomplish directly because of the constitutional prohibition on the appropriation of public education funds to private entities. In its opinion, the court aptly notes that:

“The ‘donor’ taxpayers who take advantage of this tax credit are taxpayers who, by definition, are unwilling to make charitable donations to support the laudable goals of this legislation. Rather, these taxpayers are engaging in a tax transaction; they are paying the funds (which they already owe in tax liability to the state) to private AGOs in exchange for a tax credit that eliminates their income tax liability to the extent of the payment. This tax transaction cannot accurately be characterized as a ‘donation’… In establishing this program, the legislature has essentially taken an account receivable to the Commonwealth of Kentucky, assigned it to these private AGOs and forgiven the taxpayer’s liability to the state… These taxpayers are not donating their own money to AGOs; they are taking the money they owe to the state in income taxes, and redirecting it to the AGOs as authorized by this legislation. This distinction is critical in applying the provisions of the Kentucky Constitution that govern taxation, and funding of ‘an efficient system of schools.’”

Some wealthy investors can even make money by making a “donation.” People who contribute marketable securities to an AGO can recoup up to 100% of current market value of the securities through the state tax credit and state and federal charitable deductions, but can also avoid paying the capital gains tax on any appreciation in value — meaning the benefit to these wealthy investors is greater than 100%. For example, a high-income funder holding stock with a current market value of $100,000 for which they paid $20,000 (for an $80,000 gain or increase in value) could sell the stock and walk away with $76,960 after taxes (after paying a 23.8% federal rate and 5% state rate on their $80,000 gain). But if they “donate” the appreciated stock to a private educational entity, they can make even more. Specifically, analysis from the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy shows they could receive:

- A $95,000 state tax credit;

- A $250 state tax cut from deducting the remaining $5,000 as a state charitable contribution;

- A $1,850 federal tax cut from deducting the share not reimbursed by the state tax credit as a federal charitable contribution; and

- No federal or state capital gains taxes.

As a result, the “donor” walks away with $97,100 from the gain on their $20,000 investment compared to $76,960 from simply selling the stock — an increase of $20,140 in their pocket. One can easily see that voucher programs with this design grow as big as legislators allow them to. While both this year’s proposals cap the program initially at $25 million, the growth provision would allow that cap to grow by 25% each year that at least 90% of available credits are utilized, until they reach their maximum at $50 million or $100 million. And special interests that benefit from the program will continue lobbying for its expansion, as has occurred in other states that now spend hundreds of millions each year on vouchers.

With litigation in process challenging the program established by 2021’s HB 563 on constitutional grounds, and the program suspended pending the outcome of that litigation, the General Assembly should abandon new, even more harmful legislation trying to accomplish the same goals on a grander scale. Public dollars should stay in public schools, where they are badly needed.