Legislators and advocates have been discussing bail reform for years, with general agreement that too many Kentuckians are incarcerated while awaiting trial, many because they cannot afford bail. Past bail reform efforts have stalled, however, due to a lack of data to demonstrate that pretrial release aligns with public safety goals. Yet Kentucky Supreme Court orders this year to administratively release people awaiting trial in order to reduce transmission of COVID-19 have produced the evidence.

Data from Kentucky’s Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) shows that releasing more people pretrial does not compromise public safety. Kentucky should make the emergency release orders permanent, and move forward with bail reform.

More people were released while awaiting trial in Kentucky during the pandemic

The initial order issued by the Supreme Court on April 14, 2020, expanded the existing Administrative Release (AR) program, which automatically releases some categories of individuals after arrest while they await trial, rather than leaving the decision to a judge. AR has been in place in Kentucky since 2015 but has been mandatory since 2017 for most misdemeanors and optional for many low-level felonies, although the latter option wasn’t being utilized.

The April 2020 order temporarily expanded AR to require:

- People served with a warrant for nonpayment of fines be cited and released.

- People charged with, or arrested for failing to appear in court on, any nonviolent/nonsexual Class D felony (who were not assessed as a high risk for engaging in new criminal activity) be released on recognizance (meaning they simply need to come back to court and are not subject to money bail). Class D felonies are the lowest level felonies.

- People arrested for contempt of court on a civil matter (excluding a violation of any protective order) or for nonpayment of child support or restitution be released on recognizance.

The original order was subsequently amended several times to scale back some of the categories of releases originally required, including failure to appear, rearrest after a previous AR release, civil contempt, nonpayment of child support and payment of restitution. The order currently in effect was issued on Dec. 17, 2020, and does not have an expiration date.

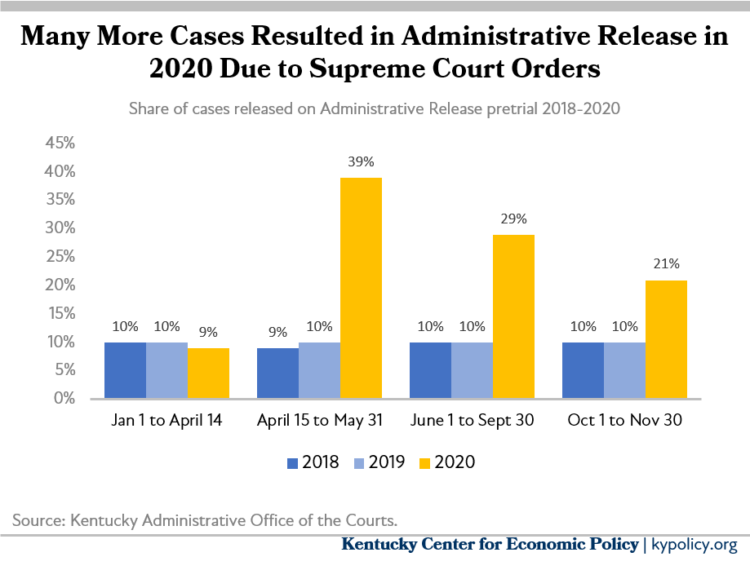

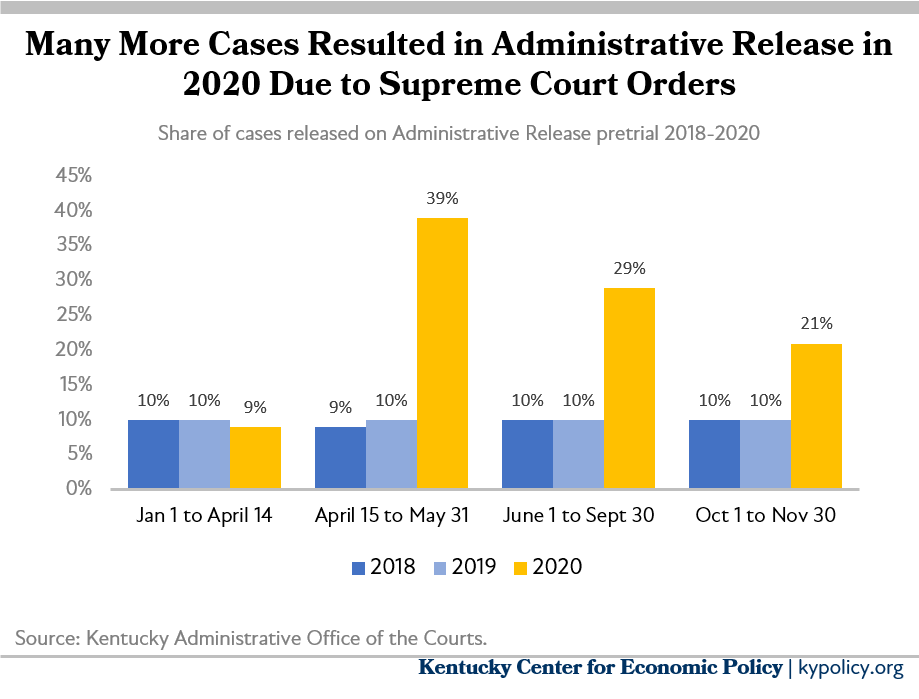

The graph below shows the significant increase in the percentage of cases that were released on AR in 2020 compared to 2018 and 2019.

The new AOC data also shows that comparing year over year data from April 15 through Nov. 30 for 2019 and 2020, the number of cases resulting in release through AR more than doubled — with 31,336 cases resulting in release in 2020 (even as arrests were down during this time period) compared to 15,281 in 2019.

The graph also shows a decline in the share of cases resulting in AR after the order was modified in June and then again October — resulting in an increase in the number of people in jail who are awaiting trial (roughly 4,490 on May 5, up to 6,121 on August 13 and up to 7,148 on December 17) and an overall increase in the jail population. These are concerning trends given the continued high rates of COVID-19.

Expanding pretrial release supports public safety

The AOC data demonstrates that at the same time thousands more people in an expanded set of categories were released pretrial due to the emergency order, the percentage of people who were subsequently rearrested has not increased substantially. In fact, 89% of those released under the emergency orders were not rearrested, compared to 92% the previous year. Furthermore, an initial presentation of data to a legislative committee this summer by AOC indicated that the rearrest of people let go through AR or otherwise had largely been for low-level offenses comparable to the charge on which they were released.

Also of note is that the rearrest rate of people released through a judicial decision rather than AR was 10% in 2020, compared to 8% in 2019 (April 15 to Nov. 30, with 82,633 releases occurring in 2019 and 50,738 in 2020). So the data does not suggest higher rates of rearrest through AR compared to those released by a judge.

While “public safety” is often solely measured in terms of number of rearrests, the health of incarcerated Kentuckians and their families and communities should also be part of such a consideration. The additional releases through AR have supported state’s public health goals because they have helped to keep jail populations lower than they were prior to the pandemic in order to somewhat mitigate the spread of COVID-19 among incarcerated individuals, jail staff and the broader community. Prior to COVID-19 — and beyond COVID-19 — there are additional health harms associated with pretrial incarceration that support the case for bail reform to improve public safety and health. For instance, pretrial incarceration threatens key upstream factors that influence health outcomes such as economic security and stable housing — as people incarcerated while awaiting trial often lose employment and housing, and are subject to fees while incarcerated.

Data from pretrial reforms in other states shows similarly positive outcomes

These promising results in Kentucky are also bolstered by recent data on the outcomes of pretrial reforms in other states. An in-depth study was recently published about the impact of an order that went into effect in Cook County, Illinois, in September 2017, which established a presumption of release without monetary bail for most people who were arrested in Cook County. The study found that the order increased the percentage and number of people released pretrial and had no effect on new criminal activity or crime; the order also reduced the financial burden on defendants by $31.4 million from Nov. 1, 2017, to Apr. 20, 2018, with the most dramatic impact on Black defendants. And just last week, Illinois lawmakers passed bail reform legislation statewide that would dramatically curb the use of money bail.

The Prison Policy Initiative also recently highlighted several states and localities that have enacted reforms to safely release more people pretrial.

Why legislative action is needed

Given the success of expanding pretrial release in Kentucky and elsewhere, continued concerns about COVID-19 transmission and other negative health impacts for people who remain incarcerated pretrial, and the fact that incarceration in Kentucky is ticking back up again, it is time for the General Assembly to act. They should make the expansion of AR permanent, further narrow the categories of individuals subject to money bail and ensure a defendant’s right to a fast and speedy trial in the event they are incarcerated while they wait.