New Census data for 2023 shows that pandemic-era policies made a big difference in reducing poverty and increasing health care coverage rates for children in Kentucky. But those supports have largely expired and Kentucky is now at risk of backsliding in these important areas.

Census data also shows that the poverty rate, inflation-adjusted median income, and uninsured rate for all Kentuckians did not show a statistically significant change from 2022, despite a strong labor market. However, it did show concerning signs of widening disparities by race for insurance and income, which were partially exacerbated by the expiration of many pandemic-era programs. In all, Census data shows that we have the tools to reduce poverty and makes it clear that these policies should be made permanent.

Child poverty was cut in half in Kentucky from post-pandemic policies

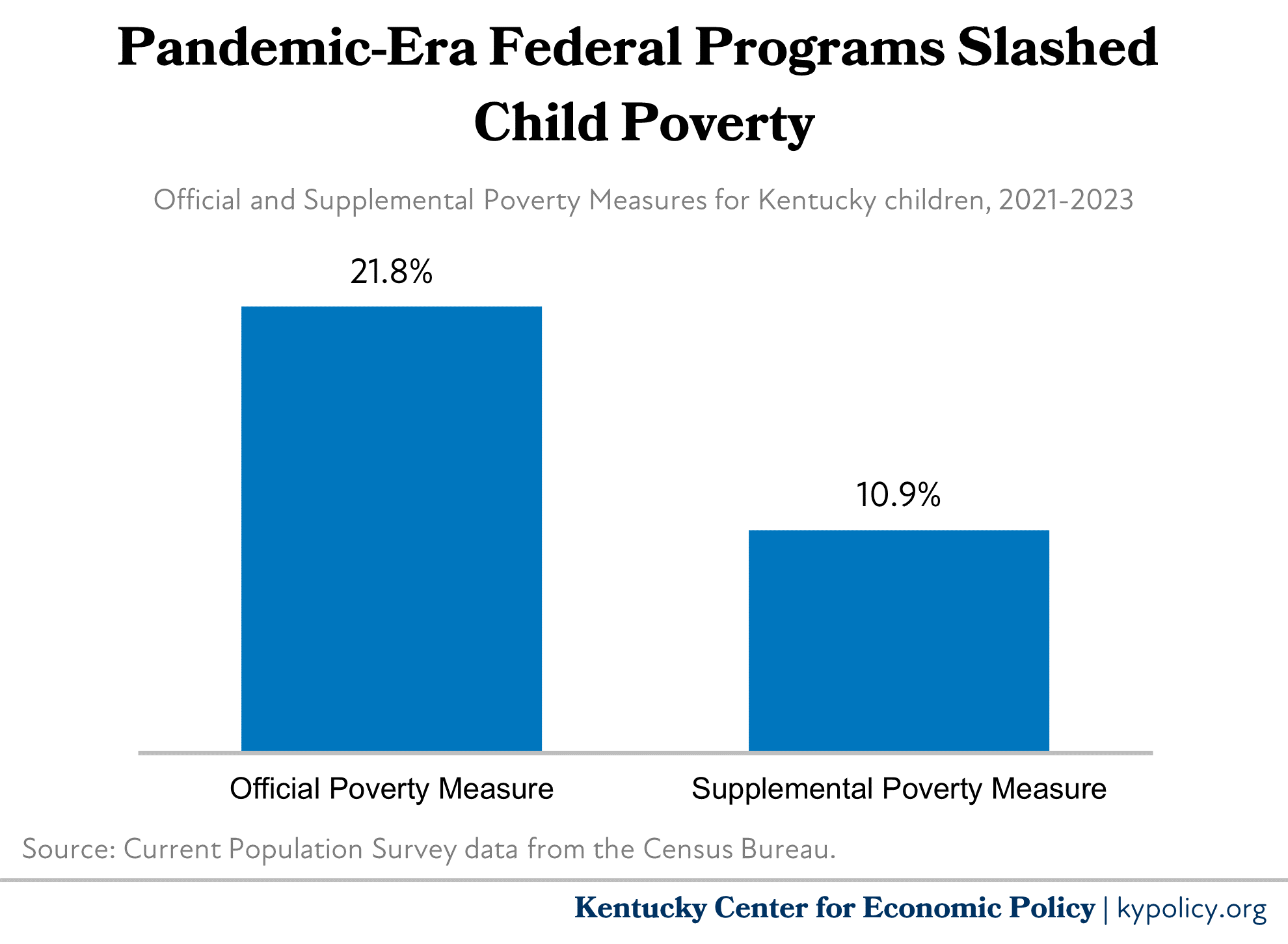

While more than one in five Kentucky kids live below the poverty line according to the official poverty measure (OPM), that number is halved once various public supports are taken into account through the supplemental poverty measure (SPM). From 2021 to 2023, federal programs designed to provide relief from the economic downturn, including boosted food assistance, utility and housing assistance, free school meals, and the enhanced Child Tax Credit (CTC), resulted in a childhood SPM of 10.9% in Kentucky. Unfortunately, as of this year, most of these supports have ended, jeopardizing the remarkable progress we’ve made in child poverty in recent years.

The change in the official poverty measure for children, and Kentuckians as a whole, was statistically insignificant between 2022 and 2023. No change was also the case in all six congressional districts, and for all races. Only Hispanic Kentuckians saw a statistically significant increase in the share of people living below the poverty line (25.8%). The poverty rate remained stubbornly high despite a strong labor market and some improvement in wages last year. In 2023, Kentucky had the fifth highest child poverty rate (21.0%) among states and the sixth highest poverty rate overall (16.4%).

More kids have health coverage this year

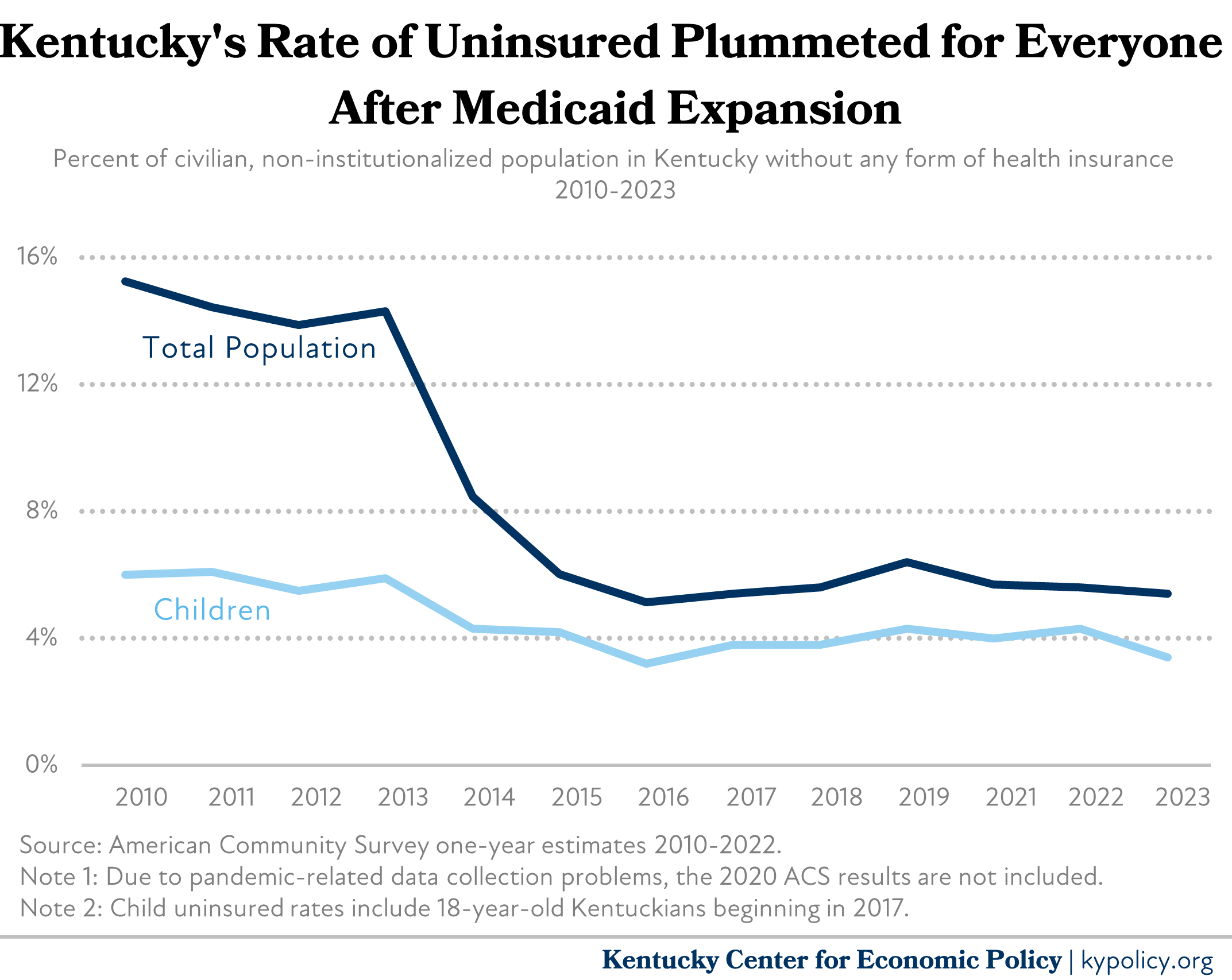

Kentuckians did not see a statistically-significant change in the uninsured rate in 2023 (5.4%) even with pandemic-era Medicaid coverage protections ending in April, 2023. By the end of 2023, 171,400 fewer Kentuckians were covered by Medicaid, a reduction of 10%. With so many losing Medicaid coverage, it is remarkable that our uninsured rate remained steady, with many receiving employer-sponsored health insurance, and others turning to our marketplace, kynect.

Kentucky received permission to keep those same pandemic-era protections in place for children, resulting in a statistically significant reduction in the share of kids without health coverage, now just 3.4%. Kentucky was the first state to receive that flexibility, and this progress demonstrates how continuous coverage in Medicaid makes a measurable difference in health coverage.

Unfortunately, the disparity between Black and white Kentuckians’ coverage status widened in 2023 by a statistically significant amount. In 2022 the coverage rates for these groups were statistically the same, the result of intentional outreach from CHFS to enroll Black Kentuckians in Medicaid and subsidized coverage on the marketplace. But while white coverage rates improved modestly (to 4.5% uninsured), Black coverage rates remained the same (at 7.1% uninsured), creating a concerning coverage gap.

Median household income did not significantly change last year

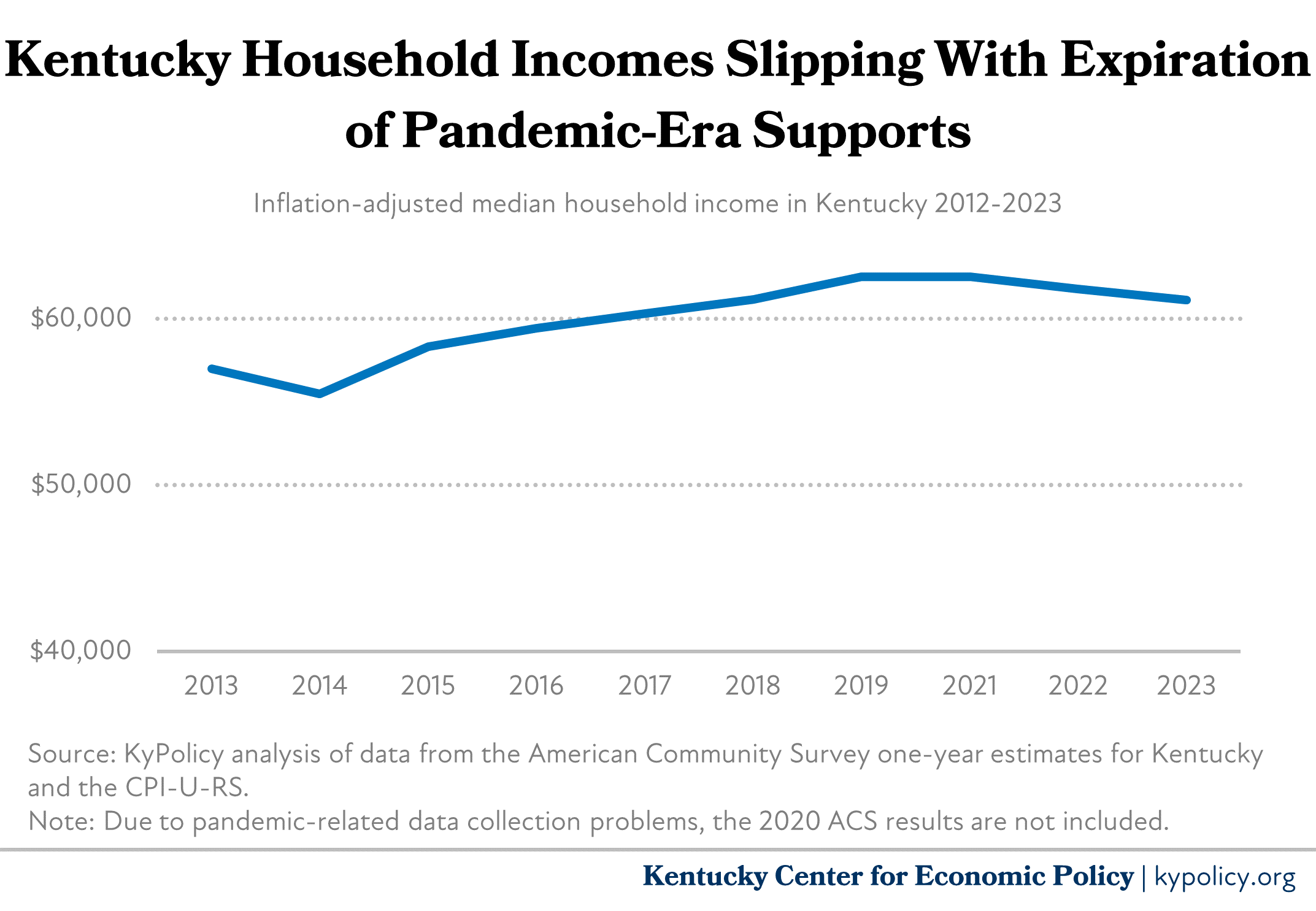

According to the most recent ACS data, Kentucky households had a median income of $61,118 last year, which was not a statistically significant change from the inflation-adjusted $61,790 in 2022. It was, however, lower than the inflation-adjusted median income in 2021 by a statistically significant $1,429.

Additionally, Black Kentucky households suffered a statistically significant $4,352 decline in their median income, from an inflation-adjusted $45,791 in 2022 to $41,439 in 2023. This was a drop of nearly 10% of an income that was already too low, and far lower than the median Kentucky household. The American Community Survey, which measured this disparity, counts income from earnings and other sources, including many of the kinds of supports provided in the wake of the pandemic, which could explain some of this decline . There have long been structural disparities built into our economy from historic policies that have yet to be corrected for, but to see such a steep decline in just one year among Black Kentucky households is especially alarming.

Pandemic-era supports showed us that cutting poverty is possible

Direct supports to Kentucky families with children led to less economic hardship, which will have echoing benefits for years to come. Knowing that we have the tools to alleviate poverty and improve health coverage rates should serve as a catalyst to make policies like the enhanced CTC, continuous coverage in Medicaid, free school meals and boosted food assistance a permanent part of our anti-poverty tool chest.