The budget passed by the General Assembly on Monday does not contain good news for higher education students in Kentucky. The 1.5 percent cuts to the state’s public universities and community colleges, new fee for community college students, and only a tiny boost to state need-based financial aid programs mean that the college affordability problem in Kentucky will continue to grow.

As described in a previous post, the cost of attending college in Kentucky has grown and is now relatively high compared to other states, and the new budget will compound this problem. Repeated decreases in state funding over the years have been the driving force that has led tuition to triple since 1998. The additional 1.5 percent cut means that funding for the state’s public higher education institutions will have declined by 27 percent between 2008 and 2016 after adjusting for inflation.

For the state’s community college students, the budget’s $8 per credit hour fee to finance construction projects throughout the Kentucky Community and Technical College System (KCTCS) is itself a 5.6 percent increase in tuition, and Kentucky’s community college tuition costs are already the 11th highest in the nation.

These increased costs will especially impact low-income students, many of whom attend community colleges. Low-income students’ decisions about whether or not to attend college are more sensitive to college costs, and the number one reason KCTCS students report for withdrawing from school is finances. The three-year graduation rate for Kentucky’s community college students is just 13 percent, and for low-income students it is under 12 percent.

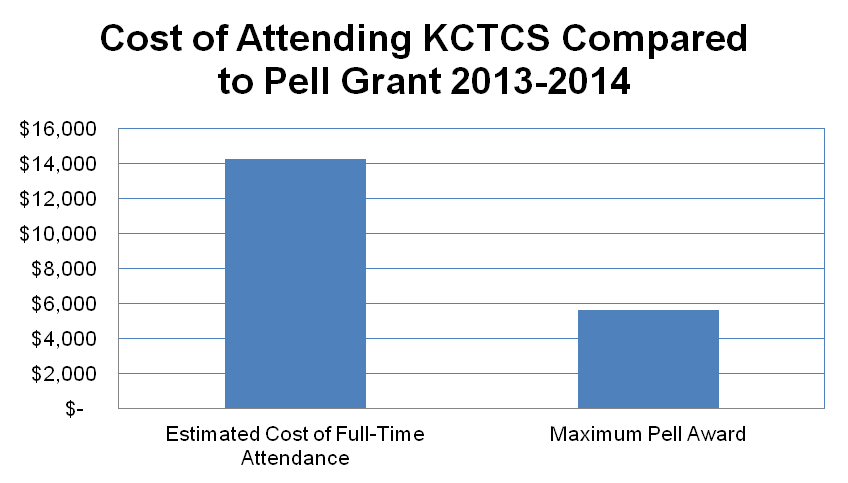

The estimated full-time cost of attendance at KCTCS (including housing and transportation, among other costs) is over $14,000 a year. These costs are becoming a barrier to degree and credential completion, especially when you take into account potential lost income from reducing work hours in order to attend school. For instance, a student working for $8 an hour would earn approximately $16,640 a year at 40 hours a week. Reducing work to 20 hours while taking college classes would mean forgoing $8,000 a year in income. This is especially an issue for adult students—and the majority of community college students fall into that category.

In addition, Kentucky does not adequately invest in state need-based financial aid programs that could help to mitigate the dramatic rises in tuition. Both the need-based College Access Program (CAP) and Kentucky Tuition Grant (KTG) are dramatically underfunded. The General Assembly may have given a tiny bump in funding to these scholarship programs—an additional $1.5 million over the biennium to both CAP and KTG—but it isn’t enough to even begin to make a dent in the large number of students who qualify for but are denied aid due to lack of funds (over 76,000 for CAP and more than 10,000 for KTG in 2012-2013).

The budget’s small increase in CAP and KTG funding also pales in comparison to the many more millions of dollars in lottery money that are being diverted from these programs each year. In addition, CAP and KTG are treated equally with the funding boost—although only CAP is truly targeted to students with the least financial resources. While CAP eligibility is determined by financial need, with KTG—which is for students who attend a private college in Kentucky—eligibility is based primarily on the cost of the college rather than the financial need of the student. More than 29 percent of KTG funds went to those with family incomes of more than $75,000 a year while less than 2 percent of CAP monies were disbursed to those in this income category.

Federal need-based Pell grants are often cited as a means of keeping college affordable for low-income students—especially at community colleges where a large share of students receive Pell—even with rising tuition and lack of state financial aid. However, Pell grants have lost much of their purchasing power. While in the 1970s Pell covered nearly 80 percent of tuition, fees, and room and board at public four-year institutions, today it pays for less than a third of these costs. Students who receive Pell are actually more than twice as likely to have student loans and have greater student debt than higher-income students who do not receive Pell.

As seen below, the maximum Pell grant covers just 40 percent of the estimated cost of attending KCTCS in 2013-2014. The maximum Pell award will increase by $85 next year, but that is far from enough to cover the unmet need for the state’s students—especially when factoring in increases in tuition and fees.

Source: Elizabethtown Community & Technical College; U.S Department of Education, Federal Student Aid.

In addition to financial barriers, community college students face other challenges that make completing a degree more difficult and would benefit from greater investments in student supports. Lack of access to services like intensive academic advising and career counseling lowers completion rates and extends the time students spend to get a degree, driving up costs further. Such investments are unlikely, however, given this new round of budget cuts.