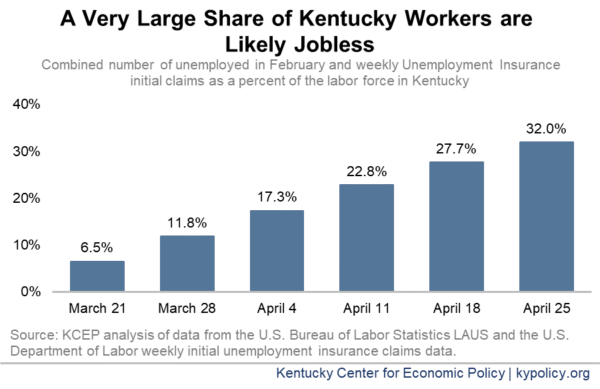

Although March’s official unemployment rate was 5.8%, once the unprecedentedly high volume of unemployment insurance claims made over the last 6 weeks is taken into account, Kentucky’s actual jobless rate could be as high as 32%. This number far exceeds historical peaks in the official unemployment rate in Kentucky – which hit 13.2% in 1983 and 11.9% in 2010 at the depths of the Great Recession.

Keeping people at home – and in many cases out of work – is key to ensuring the reduction of COVID-19 infections. But it also points to the need for much more help at the federal level for individuals and communities that will likely be digging out of this economic downturn for a long time to come.

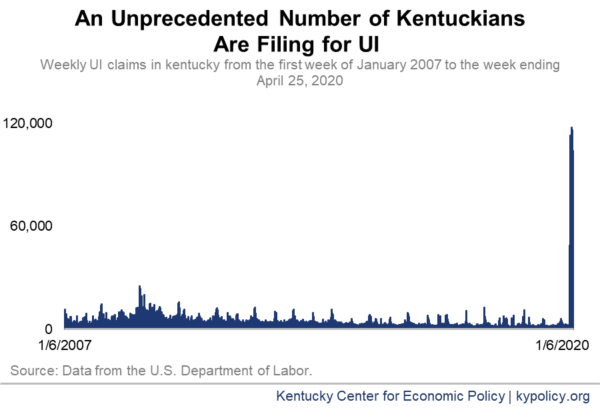

Initial unemployment insurance claims are extremely high

Since the week ending March 21, 590,829 Kentuckians have applied for unemployment insurance (UI), which is more than a quarter of total employment in the state (a little over 2 million). To put that into perspective, the average number of weekly claims during this six-week period was 98,472, whereas the average weekly claims in 2019 was 3,048 and the highest number of weekly claims during the Great Recession was 25,588.

The number of Kentuckians without a job is much higher than the most recent unemployment rate

Adding the number of Kentuckians with initial UI claims in the last 6 weeks to the official number of unemployed Kentuckians in February (the month before social distancing policies began going into effect), translates from an unemployment rate of 4.2% to an equivalent of 32% by the third week of April.

Combining the unemployment rate and unemployment insurance claim filings provides a more comprehensive picture of the state of Kentucky’s workforce than the unemployment rate alone. The most recent unemployment rate doesn’t tell the full story because the survey conducted to calculate the unemployment rate asks participants about their job status for the week during which the 12th of the month falls, which for the March rate was the week prior to the Governor’s orders to close public-facing businesses like restaurants and retail stores. In the near future, the unemployment rate is likely to be lower than actual joblessness because the questionnaire used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics asks if an individual was looking for a job to determine if the participant was unemployed. If an individual is not employed and not looking for a job, they are not included as a part of the labor force and are excluded from the data. Many who are out of a job right now are not looking for work because public-facing businesses have not yet reopened and Kentuckians are following “healthy at home” guidelines. Therefore, adding new unemployment claims since closings began helps get a better sense of the scope of joblessness.

However, this is more of an approximation than an esitmate — and there are some caveats. Initial claims data don’t capture the detail necessary to provide a true estimate. For example, some who file for unemployment request what is known as “partial unemployment” where their hours were reduced and they are only seeking to replace some of their lost wages, but are not jobless. Also possibly inflating the estimate somewhat, a small share of individuals who were counted in the unemployment rate in February gained and then lost employment again since then, leading to a double count. And some who filed for unemployment insurance in the early weeks of the crisis may have gone back to a different job, like a child care worker who was laid off and went to work at a grocery store or retail warehouse, for example. Also, due to delays in processing claims, some Kentuckians have erroneously applied for UI more than once, and so would be double counted in the initial claims data. Still, it is very likely that hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians are not at work right now.

More is needed to ensure a robust recovery

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the CARES Act have been meaningful steps in addressing the pandemic and consequential economic downturn, and were appropriate early in the pandemic. But now, as the extent of the economic fallout has become clearer, much more needs to be done to help Kentuckians and their families weather the loss of employment and income caused by COVID-19.

Additional rounds of direct stimulus payments to individuals; an extension of joblessness benefits like the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance and Pandemic Unemployment Compensation; boosts in food, housing and basic cash assistance; an expansion of health coverage for those who lost it; and large, flexible direct payments to state and local governments — among other policies — are necessary now and will continue to be once the COVID-19 pandemic subsides and the work of recovery begins.

Updated May 4, 2020.