Kentucky’s economy has garnered headlines for the decline in the state’s unemployment rate, which fell sharply from 7.9 percent in December 2013 to just 5.7 percent in December 2014. However, that number overstates how good the job situation is in Kentucky because of who it leaves out.

It’s true that the state’s job growth has picked up over the last year. After averaging just about 1,400 new jobs a month in 2013, the state added around 2,700 new jobs a month in 2014.

But growth in jobs only partially explains the drop in Kentucky’s unemployment rate. Unless a jobless adult is actively seeking work, they aren’t counted as unemployed or factored in the unemployment rate. And there is evidence that these unaccounted for “missing workers” are a large and even growing share of people still in need of employment.

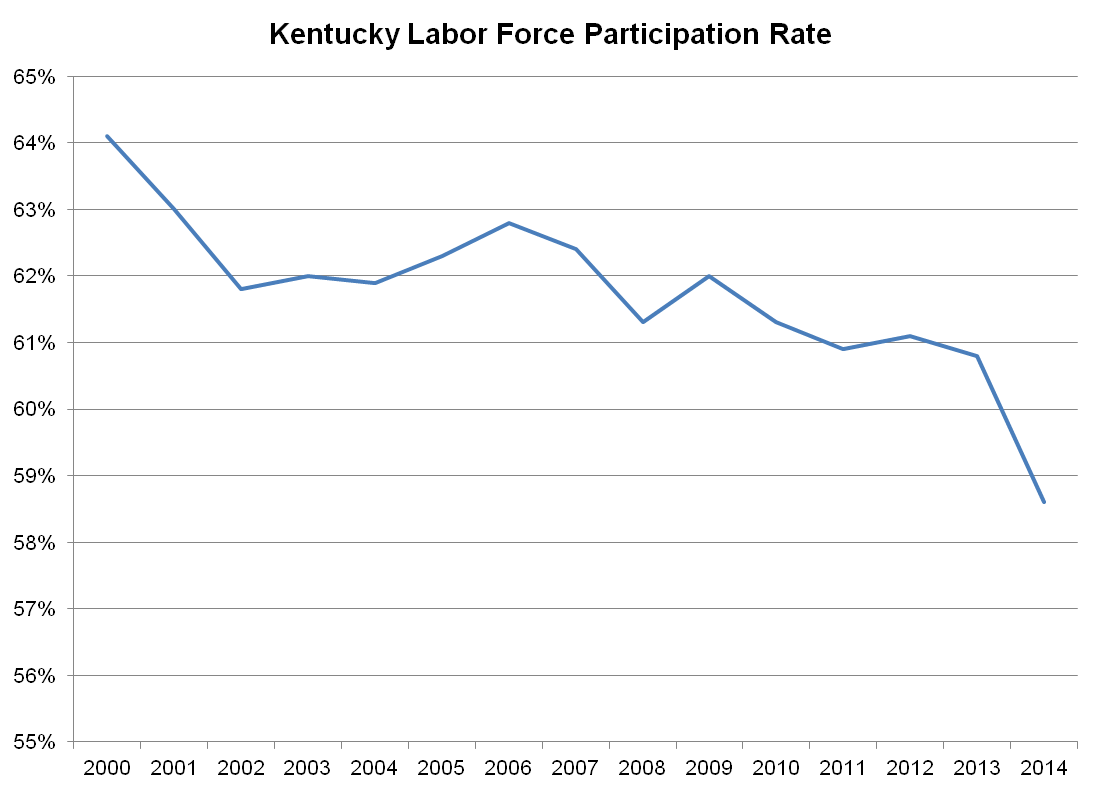

Kentucky’s missing worker problem can be seen in the state’s declining labor force participation rate, a measure of the share of adults who either have a job or are seeking work. Participation has dropped in the years since 2000, as seen in the graph below, and fell a statistically significant 2.2 percentage points between 2013 and 2014.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

The rate also fell for the nation as a whole since 2000, in part because the early 2000s recession and the Great Recession created a shortage of available jobs. As the weak economy has dragged on, some discouraged workers have given up looking for work, while other young people have never entered the labor force to begin with. Men are especially represented among missing workers, as are those with a high school degree or less.

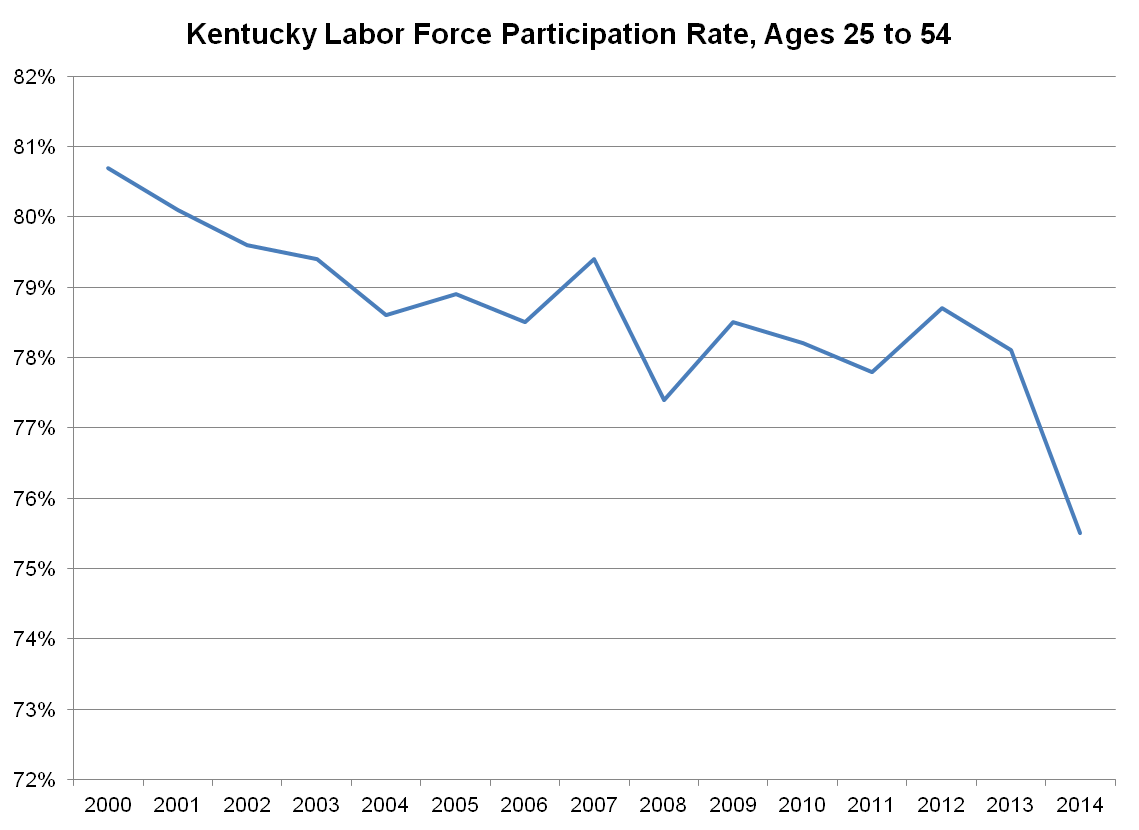

Although a baby boomer population aging out of the workforce plays a role in this trend nationally, the problem can’t be attributed simply to that. As shown in the graph below, the decline in the labor force participation rate also applies to prime-age workers, those ages 25 to 54. In 2014, that number dropped by a statistically significant 2.6 percentage points in Kentucky to the worst recorded rate in the last 35 years. Kentucky’s rate in 2014 is the third-worst in the country, behind only West Virginia and Mississippi.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

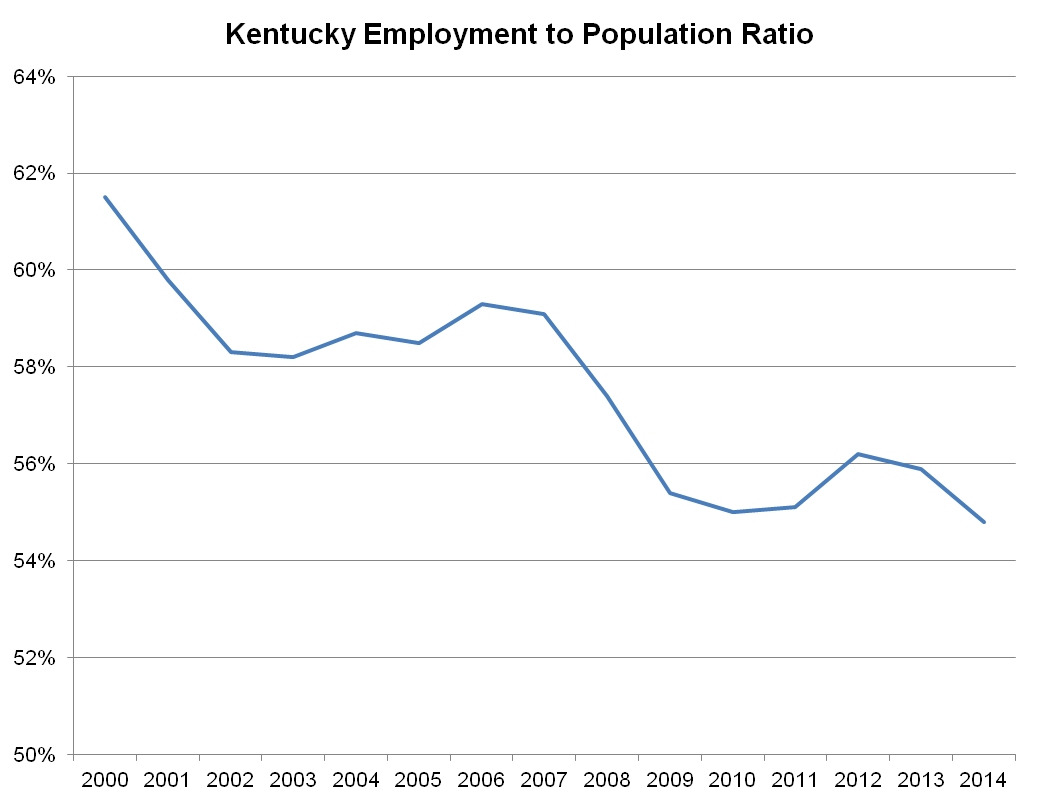

The net effect of the growth in jobs and the drop in the labor force can be seen by looking at another measure: the share of the adult population with a job, or the employment-to-population ratio. That number also fell in Kentucky between 2013 and 2014 by 1.1 percentage points, and by 0.8 percentage points for prime-age workers (though that decline was not statistically significant). So while the unemployment rate went down in 2014, a smaller share of adult workers is employed than in the previous year.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

This trend means that Kentucky needs many more jobs to fully recover from the recession than the falling unemployment rate implies. To have the same employment-to-population ratio in 2014 than the state had back in 2000, when the economy was particularly strong, would mean that 230,000 more Kentuckians had jobs. To put that in context, Kentucky has created only 130,000 jobs since the recovery began in 2010.

While Kentuckians’ health and education also contribute to our low labor force participation rate, our much-higher rate in 2000 suggests that if more jobs were available in a generally stronger economy, a lot more people would enter the workforce.

Kentucky’s persistent missing workers problem should add urgency to efforts to create jobs in the short-term and spur a faster recovery, including through investments across the Commonwealth in areas like infrastructure and land remediation. It should also mean that state and national leaders avoid further budget cuts and interest rate increases that would choke off the fledgling recovery.