With the recent guidance by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on work requirements, it is very likely that Kentucky’s request to implement a “community engagement” condition of Medicaid eligibility will be approved. Work requirements for public benefits are harmful, and don’t achieve their supposed goals of reducing poverty, promoting long-term economic advancement and making people healthier. Cutting off peoples’ ability to get to a doctor when they need to only makes it harder for them to keep working, or find meaningful employment. Rather than punishing people who are working low-wage jobs with unpredictable hours or looking for work in economically depressed parts of the commonwealth, we should instead focus on policies that help create jobs and boost wages.

The requirement would make eligibility for coverage conditional on 20 hours a week of some work-related activity. Embedded in the work requirement is the false premise that people covered by Medicaid are not working, or would be encouraged to increase their work hours if they were threatened with the prospect of losing health coverage through Medicaid. This assumption is wrong on multiple levels.

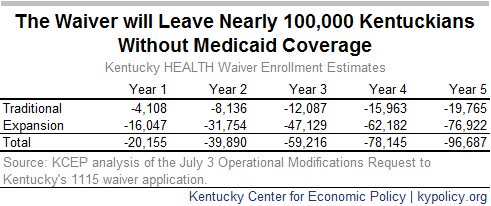

Work requirements would result in decreased enrollment

In the latest request to make changes to Kentucky’s Medicaid program, the state says that provisions around premium payments and the work requirement would result in the enrollment decrease:

“It is anticipated that enrollment in Kentucky HEALTH will fluctuate for a variety of reasons, including program noncompliance. Members may have health coverage temporarily suspended for not meeting the community engagement and employment initiative requirements, failing to pay required monthly premiums, or failing to report a change in circumstances.”

Indeed, because some Medicaid enrollees would be unable to meet the requirements either because they failed to report the work they did on time or because work was unavailable where they lived, many would lose coverage altogether.

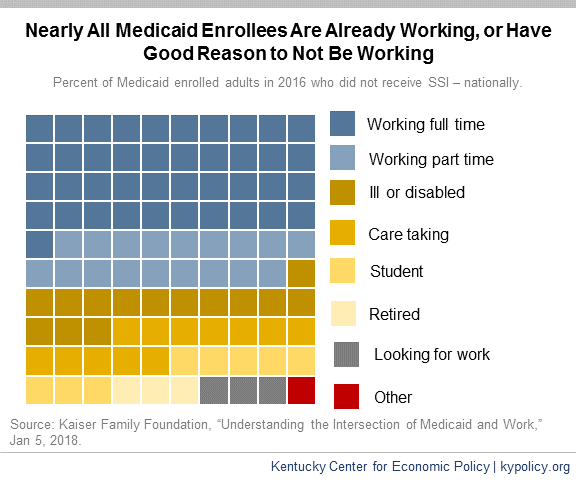

Most Medicaid enrollees who can work do work

In Kentucky, the majority of Medicaid expansion enrollees currently work, and four out of five adult Medicaid expansion enrollees have worked at some point in the past five years. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that 51 percent of Kentucky Medicaid-covered adults currently work, and 66 percent come from working families.

Of those who do not work, most are ill or disabled, taking care of a loved one, or are in school or retired. Kaiser estimates that, nationally, all but 4.5 percent of Medicaid-enrolled adults are working or meet one of those criteria. Of the 4.5 percent who either do not work or have a good reason not to, 3.3 percent are looking for work and just 1.2 percent are not.

Work requirements ignore economic realities in Kentucky

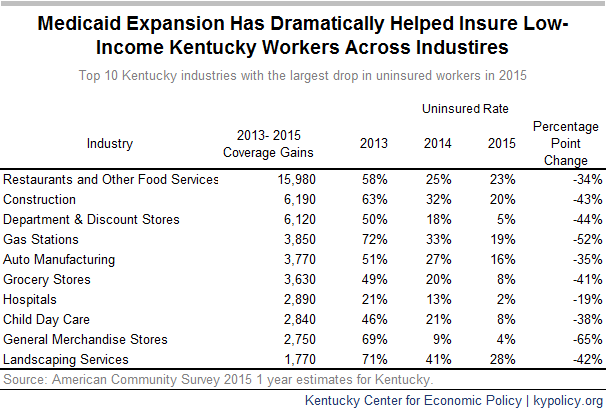

Of the working Medicaid-eligible adults in Kentucky 11 percent work less than 20 hours per week whereas 54 percent work 35 hours per week or more.[1] The problem is that they work in industries with inconsistent hours and incomes. As of 2015, the three industries that employed the most Medicaid expansion-eligible adults in Kentucky were restaurants, construction and department stores — all known for irregular scheduling. In retail, hours change weekly or even day-of; restaurant workers depend on tips, which vary greatly, especially when shared; and construction work is seasonal and often depends on weather conditions as well as the location of construction projects.

Low-wage workers face a number of challenges that would make the reporting requirement onerous. According to the Center for Law and Social Policy, many low-income workers are employed in jobs that have:

- Inadequate hours.

- Highly variable hours on a weekly basis.

- Little advance notice of shifts, including being sent home early or called in right before a shift begins because of growing use of management strategies like “just-in-time” scheduling.

- Split shifts or on-call shifts.

In each of these cases, wages and hours vary on a week-to-week basis. But the proposed waiver requires that such changes must be reported to the Cabinet within a 10 day period. This would be burdensome for both the enrollee and the state, and would almost certainly result in people churning on and off Medicaid leading to higher administrative burden and disrupted care for low-income workers.

Low-income workers often are forced to work fewer hours than they would prefer. According to the Department of Labor, over 5 million Americans work part time involuntarily and would work more if their place of work offered more hours or they could find full time jobs.

There is also a disconnect between the work requirement and the jobs that are available. As of 2016 there were 99,700 Kentuckians without work, but looking for a job. If enrollment estimates from Indiana’s work requirement request are similar to how Kentucky’s, then roughly 128,000 Kentuckians will have to adhere to the work requirement. While, as mentioned previously, most of these already work, many will still be competing for scarce jobs.

Between 2009 and 2017, 32 Kentucky counties saw the total number of jobs decline between 10 and 32 percent. Roughly 3/4 of Kentucky counties saw either modest job growth of less than 10 percent or a decline in jobs during that time frame. Too few job opportunities especially in the rural areas of the state; barriers to gainful employment or advancement like criminal records, lack of access to child care and transportation, and poor health; and a lack of income supports and adequate wages are primarily what is holding back unemployed and underemployed Medicaid enrollees from better economic mobility.

Work requirements do not promote long-term employment or reduce poverty

An established body of research shows work requirements do not reduce poverty or succeed in helping people obtain long term, permanent employment. Among those who received cash assistance through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) since its creation in 1996, work requirements have not yielded long-term results. One review of 13 randomly assigned studies showed a work requirement resulted in a short-term increase in employment, but employment outcomes faded after 2 years and the requirement didn’t have any effect on employment 5 years afterward. In fact, the study showed most participants were not employed 75 percent or more of the time, 3 to 5 years out from their participation in TANF-required work activity.[2] The communities that have shown significant long-term employment effects through a program that required work as a condition of eligibility were in Portland, OR, and Riverside, CA. In those communities program administrators offered significant work supports and training, and encouraged participants to hold out for better jobs with higher wages that offered more opportunity for advancement.

Most individuals subject to work requirements remain in poverty, and in some cases become poorer. An evaluation of 11 programs that offered cash assistance and SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) showed that the percent of TANF participants living in poverty in the observed communities didn’t change 2 years after participation, and the percent living in deep poverty (half of the poverty level or less) increased in 6 of the 11 communities.

Work requirements are ineffective as a condition of eligibility for public benefits because they do nothing to change either an individual’s job qualifications, ability to afford job training and education or the existence of decent job opportunities in the labor market in which he or she is trying to navigate.

Work supports, not threats of eliminated coverage, should help low-income workers

Kentucky has many options to help people move into jobs that offer opportunities for economic advancement and pathways out of poverty. Need-based financial aid for community college or four-year degrees boost Kentuckians’ chances for a middle-class job. Raising the minimum wage could boost many out of poverty and spur local economies, not to mention save the state tens of millions in Medicaid spending. Offering substantive job training like what was provided in Riverside and Portland could send many on their way to meaningful, long-term employment. But even that possibility is precluded under the CMS guidance as states cannot use federal Medicaid funds for additional work supports.

Using work status as a way of reducing enrollment is antithetical to the goal of Medicaid, which is to provide medical care for more Americans.

[1] Data are from the 2016 American Community Survey one year estimates for Kentucky adults under 64 years old who earn less than 139% of the Federal Poverty Level and do not receive SSI.

[2] Jeffrey Grogger & Lynn A. Karoly, Welfare Reform: Effects of a Decade of Change, Harvard University Press, 2005.