For a PDF version of the report, click here.

Summary

Kentucky and its policymakers need accurate indicators to measure the strength of the state economy and to understand the impact of policies on jobs and economic well-being. Announcements of potential private business investments by the state’s Cabinet for Economic Development are consistently touted by political leaders. But relying on these announcements as a barometer of economic success can put the state’s economy in a more positive light than is warranted.

Cabinet announcements sometimes involve little if any new job creation, and describe only potential and not actual economic activity. Starting in 2016, announcement reports are no longer counterbalanced by reports from the Cabinet on jobs that are lost through facility closings or downsizings. What’s more, much private job activity happens outside of official announcements through small business start-up and existing business expansion and contraction. One-dimensional announcement reports also have been misused to make inaccurate claims about the impact of policies like Right to Work (RTW).

Recently, the state has promoted the $9.2 billion in potential future private investment the Cabinet announced in 2017 (a level that did not continue into 2018, where announced investments total $4.35 billion as of October 2018).1 A closer look at the details reveals a substantial share of these announcements are not connected to any new jobs, and the total includes investments that may never occur. In addition, the vast majority of projected new investments are from companies that were already operating in Kentucky prior to 2017, as opposed to outside companies choosing to invest in Kentucky for the first time, raising serious doubts about claims the investments result from recent policy changes.

Rather than relying primarily on the rosy picture painted by these announcements in understanding and evaluating the strength of our economy, we need to consider other information to get an accurate understanding of what drives economic growth and how Kentucky is performing. Rigorous research shows the vast majority of new private sector jobs are created by existing, often young companies within a state, rather than from new investment by businesses coming from outside. Public investments in areas like education and infrastructure are the most powerful policy drivers of that growth, rather than often-counterproductive tax breaks, incentives or policies to reduce worker wages and benefits.

Importantly, official job and wage data from sources like the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the fullest picture of employment. That data in Kentucky contradicts the soaring claims of an economic boom based primarily on Cabinet announcements of new investments. Official data shows Kentucky’s economy has had no recent acceleration in job growth, and in fact employment growth — including manufacturing job growth — has weakened the last few years.

Announcements Are Not What Is Claimed

Kentucky’s Cabinet for Economic Development markets the state to prospective employers and is empowered by statute to offer tax breaks to businesses. On a regular basis, the Cabinet issues press releases and reports highlighting companies that have announced plans to expand or locate in the state. These reports are often used by elected officials at all levels of government to make claims about the importance of certain policies or politicians’ own influence on those companies’ decisions.

Recently, a Cabinet for Economic Development report listing companies that have announced plans to expand or locate in Kentucky in 2017 has received considerable attention.2 The sum of all announced investments included in that report total $9.2 billion, which the Bevin administration says beats the previous record for announcements set in 2015.3 Political leaders claim the increase was caused by passage of a state RTW law and other “business-friendly” legislation passed in 2017. In the release announcing the $9.2 billion total in new investments, the governor stated: “Kentucky’s record-setting performance this year in job creation and corporate investment is the direct result of the pro-business legislation, policies and programs we’ve enacted over the past two years.” This sentiment was echoed by acting Speaker of the House David Osborne, Senate President Robert Stivers and Cabinet Secretary Terry Gill, all of whom specifically cite RTW as a key factor.4 Rather than supporting these claims, the evidence actually paints a much different picture.

It is important to recognize this $9.2 billion number for what it is: announcements by companies of current plans to make capital investments (in equipment, land and/or buildings) in the state sometime in the future. It is not a number that identifies actual jobs created or actual investments made. And it does not consider jobs that are eliminated and businesses that are closed or downsized in a particular year, or most small business activity.

A close look at the Cabinet’s report suggests caution in drawing broad conclusions from the $9.2 billion projection.

A significant portion of projects will create no new jobs, and announcements do not guarantee projects will eventually materialize

The announcement of a potential new investment doesn’t mean any new jobs will be created for Kentuckians. In the Cabinet’s report, $502 million of the announced investments create zero new Kentucky jobs, and another $378 million do not have new jobs identified in the report. That means at least 9.6 percent of the $9.2 billion in possible investments could have no new jobs attached.

And that share grows larger once the questionable categorization of other jobs data in the report is considered. For example, the report identifies 1,209 jobs associated with Toyota’s $1.33 billion investment in Georgetown. But multiple news stories indicate that no new jobs were connected to this investment, and Cabinet information associated with the granting of $43.5 million in tax breaks for the project note the subsidies are for job retention, not job creation. The agreement actually allows Toyota to eliminate 788 jobs and still qualify for these tax breaks.5 Additionally, the report identifies 500 jobs associated with the $900 million investment Ford is making in its Louisville Truck plant. But news stories of the announcement note there are no new jobs associated with the project — only the retention of jobs — and Ford did not receive state tax breaks to create new jobs under the investment.6 Ford had previously made a $1.3 billion investment in that facility that resulted in 2,000 new jobs, but that was in 2015 before RTW or any other of the often-referenced state policies were law.

In addition, not all announcements will necessarily materialize. The Braidy Industries project in Greenup County is $1.3 billion of the $9.2 billion in investment, and is projected to create 550 jobs. But as of fall 2018, Braidy Industries lacked the financing to get the project off the ground. As the Courier-Journal reported, the company is far from raising the funds needed to build the $1.68 billion facility. As of September 2018, Braidy was seeking a $1 billion federal loan, $500 million in credit from the government of Germany and $400 million from a crowdfunded sale of stock.7 Braidy “claims it has pre-sold twice the capacity of the mills for its first seven years of operation, but the company told the SEC: ‘None of the prospective customers who have indicated a desire to purchase aluminum from Braidy are contractually committed to do so.’” Another Courier-Journal investigation found that the CEO of the company, Craig Bouchard, has a history in which “past ventures show frequent predictions of spectacular success followed by financial problems and notable failures.”8

If the lack of new jobs related to the 2017 investments by Toyota and Ford are added to the investment in projects without jobs identified above, $3.1 billion or 34 percent of the claimed $9.2 billion in projected investment is not connected to new jobs in Kentucky. If the Braidy Industries project does not end up materializing, $4.4 billion or 48 percent of the announcements have no new jobs attached.

Cabinet no longer reports jobs being eliminated from facilities closing

For many years — along with the annual report listing announcements of companies pledging to invest in Kentucky — the Cabinet for Economic Development also produced a report listing facilities that closed in the state. Because every job that is eliminated offsets every job created, tallying job losses is essential to understanding economic conditions in a state. While the Cabinet published annual facility closing reports at least as far back as 1995, the last report was published online in 2015.9 For 2016-2018, there are no published reports on facility closings.

Plant closings can be very significant. The last report from 2015 tabulated the loss of 2,319 jobs from 51 facilities closing.10 Many closings and layoffs can be separately identified from federal Worker Adjustment Retraining Notification (WARN) Act filings, which count 3,721 jobs lost so far in 2018. Closings in the last few years include GE Lexington Lamp Plant (127 jobs), Kentucky Electric Steel in Boyd County (113 jobs), the Toyota engineering and manufacturing headquarters in Boone County (648 jobs), Delta Airlines in the northern Kentucky airport (305 jobs), Dana Commercial Vehicle Manufacturing in Barren County (191 jobs), Belden Wiring in Wayne County (230 jobs) Johnson Controls in Shelby County (122 jobs) and American Greetings in Bardstown (275 jobs).11 Trane recently announced it is closing its Lexington plant next year, resulting in 600 jobs lost, and Ledvance will be closing its Versailles plant, laying off 260 employees.12

A vast majority of companies making announcements were already operating in Kentucky, many due to geographic location

Of the projects identified in the Cabinet report, 82 percent are expansions of existing businesses and not new companies coming into the state. Thus the vast majority of listed businesses were operating in the state prior to the passage of RTW and any other recent policies. In a growing economy — the United States economy has been in recovery since 2010, one of the longest economic recoveries on record —some businesses will add employees and expand operations at existing facilities in any given year as consumption grows and investment needs emerge. A total of 26 percent of the projected $9.2 billion in investment included in the report comes from just two companies: Ford (a unionized company) and Toyota, which have been operating for decades in Kentucky and which were already the second- and third-largest employers in the state with a combined 24,058 Kentucky employees in 2016.13

What’s more, some of the projects identified as “new investments” rather than expansions in the report are actually projects from companies that are already operating in Kentucky. These companies had a rationale for being located in Kentucky before any of the recent laws went into effect. One example of this type of expansion is a $60 million Kroger distribution center, which is being established to serve its many stores across the state. Another is Amazon’s announcement of a $1.494 billion investment to open an air cargo hub at Cincinnati/northern Kentucky airport that will employ 2,700 people, 600 of which are full-time jobs. This project is categorized as a “new investment,” and although the facility itself is new, Amazon is not at all new to Kentucky. Amazon opened its first warehousing facility in Kentucky in 2000, and already has 14 such facilities across the state, more than any state but California and Texas, plus a customer service center.14 Before the new announcement, Amazon had 7,232 employees in Kentucky according to the state (and as many as 10,000 employees according to Amazon), making it the 5th-largest employer.15

It makes sense for Amazon to locate and expand in Kentucky given the company’s business model and the state’s central location relative to the U.S. population. Amazon is a massive company. It is larger than most brick and mortar retailers added together, is the world’s fourth-most valuable company and is responsible for 43 percent of all online sales.16 Amazon makes decisions according to its global business strategy to sell and ship a wide variety of goods to consumers as quickly as possible.17

In announcing the air cargo hub in Kentucky, the company stated: “As we considered places for the long-term home of our air hub operations, Hebron quickly rose to the top of the list with a large, skilled workforce, centralized location with great connectivity to our nearby fulfillment locations, and an excellent quality of living for employees.”18 Location is the reason Kentucky is already a shipping hub for UPS, with its Worldport facility adjoining the Louisville airport; DHL, which has a hub at the northern Kentucky airport; and FedEx, which has a 303,000 square foot facility in Louisville.19

In the case of the air cargo hub, Amazon was able to take advantage of a large and centrally-located airport that is underutilized following the closing of the Delta hub. If anything, the success of the Amazon Air location can be linked back to President Roosevelt and Congress’ initial public investment in the airport in the 1940s, rather than any recent law change in Kentucky or tax break offered to Amazon.

Timing of announcements makes link to recent policy changes implausible

Large corporations do not make immediate decisions to invest or expand, but only after careful planning and deliberation that often takes years. Many of the announcements most-cited by the governor’s office from 2017 happened early in the year, very shortly after RTW became law. RTW passed the Kentucky legislature on Jan. 7, 2017 and was signed by the governor on Jan. 9.20 Amazon’s announcement came only three and a half weeks later, on Jan. 31.21 Toyota announced its investment on April 10 and Ford on June 20.

It is implausible that these three companies, already heavily present in Kentucky prior to RTW and unionized in the case of Ford, made these complex decisions because of such a law passing. In the case of the auto companies, the expansions were a response to growth in the demand for new cars in the post-recession recovery. Amazon is expanding everywhere as it dominates the retail sector. Within a month of announcing the Kentucky air cargo hub the company also announced new facilities in three non-RTW states (Maryland, Colorado and California) and two other RTW states (Florida and Texas).22

Wages and job quality are not clear and standards are too low

The Cabinet report cataloguing potential private investment includes nothing about the quality or wages of the prospective new jobs. For an economy to be truly booming, wages should be rising and new jobs should provide an adequate standard of living. An inattention to wages is a consistent problem with the state’s standards and reporting about companies receiving tax breaks.

The Cabinet’s main tax subsidy, the Kentucky Business Investment (KBI) program, requires a threshold for employee compensation that varies by the economic status of the county where the project is located. For 40 more prosperous counties, 90 percent of full-time jobs must pay at least $10.88 an hour plus benefits equal in value to 15 percent of that amount. In the other 80 poorer counties, 90 percent of jobs must pay at least $9.06 an hour plus 15 percent for benefits.23

These standards are too low and have been frozen for nearly a decade. They are set in state law as a multiple of the federal minimum wage, which at $7.25 an hour has not increased since 2009. Wages at this level would fail to put a family of 3 above the poverty line in the poorest 80 counties or a family of 4 above poverty in any county. And since wages for 10 percent of the jobs created can fall below this benchmark, some jobs subsidized by state government could pay wages as low as $7.25 an hour, which is also the state minimum wage. A total of 29 states have a higher minimum wage, with some phasing up to wages as high as $15 an hour, and many adjust annually for inflation.24

What’s more, a benefits package at 15 percent of the above wages equals a minimum of only $2,718 to $3,264 a year for a full-time worker. U.S. employer premium contributions for single health insurance coverage average $5,711, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.25

Because these thresholds are so low, Kentucky is subsidizing the creation of jobs that provide wages and benefits that are significantly below the typical jobs in many counties. Workers at just the 10th percentile of wages make $9.01 an hour in Kentucky (meaning only 10 percent of workers make less), and workers at the 20th percentile make $10.50 an hour.26

In addition to problems with standards, there are problems with inadequate reporting from companies that receive tax breaks. The state’s online database of businesses awarded tax breaks reports only the “estimated average hourly wage” of the business receiving incentives.27 This wage is only a projection of what will be paid. In addition, average wages do not communicate what the typical worker makes, or what the lowest-paid worker receives, both of which are important for understanding job quality. A few highly-paid executives, some of whom are relocated from outside a community, can skew the average wage to make it much higher than the wages of most workers.

There are also no published follow-up reports after the initial announcement of a project and awarding of incentives that provide information about the actual number of new jobs created, or actual wages paid. To qualify for incentives under the KBI program, only 10 new full-time jobs are required, and agreements can and often are amended to reduce initial projections on jobs and wages as projects move forward.

Return on investment for tax breaks is not scrutinized

Kentucky is providing substantial tax breaks for most all of the projects identified in the Cabinet’s announcement report. But those tax breaks are rarely studied for their cost-effectiveness and return on investment, in part because data is not collected and reported, as indicated above. The studies that do exist suggest little bang for the buck.

For calendar year 2017 — the period that corresponds with the Cabinet’s announcements — Kentucky gave away $361 million in tax incentives, according to the state’s website.28 Those tax subsidies come from an expanding menu of business incentive programs that are a growing drain on the state budget.

These programs do not just provide tax forgiveness; the largest and most expensive of the subsidies are called wage assessments. A wage assessment diverts income taxes withheld by the company from employees’ paychecks that would otherwise be paid by the business to the commonwealth, and instead allows the company to retain those amounts. At the same time, employees whose state income tax payments are being retained by their employer are given credit for having paid their taxes. Kentucky originated this method of returning state tax money to corporations because companies often pay very little or no corporate income taxes, so simply providing credits against that tax would not provide as significant a subsidy.

Only two studies in the past have taken a close look at Kentucky’s tax subsidies. The first, a 2007 report by the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Kentucky, estimated that these programs cost a hefty $26,775 per associated job, a number much higher than the estimated $2,510 per job through a job training program.29 Similarly, a report by Anderson Economic Group in 2012 found that 35 percent of the jobs associated with tax incentives would have to be created solely as a result of the state’s tax breaks – and not other factors – in order for them to be cost effective.30 But rigorous research finds tax breaks only modestly influence business decision making, and can be harmful after taking into account the opportunity cost of not investing those same dollars in high-return public investments like early childhood education.31

There are special tax breaks for the very large projects included in the Cabinet’s 2017 announcements report. The Toyota expansion received $43.5 million in a rarely used subsidy only for companies that are expected to create no new jobs. The Amazon Air project received $40 million in tax breaks in addition to a jet fuel tax subsidy valued at $3 million, which required special legislation of the General Assembly to make possible.32 And in addition to $15 million in tax subsidies, Braidy Industries also benefited from a unique $15 million direct state purchase of equity, amounting to more than 20 percent ownership of the company. Braidy also received $5 million in public money to build adjoining roads, $2 million for training and a $4 million federal grant of abandoned mine lands monies to prepare a strip mine site for the facility.33

What Really Goes Into Economic Development

A serious problem with relying heavily on Cabinet announcements to understand the economy is that it can lead to an exaggerated perception of the role of business recruitment in state economic growth. Research shows more than 80 percent of the jobs created in a state in any given year are from start-ups of new businesses and expansions of existing companies already located in-state. Out-of-state businesses opening new branches in a state create only 7 to 14 percent of new jobs, while companies picking up and relocating from another state are only 1 to 4 percent of job creation. There is too much focus on policies aimed at luring businesses, with politicians hoping to land the “big fish.” Most job creation is much more mundane than what is represented in ribbon cuttings, and comes from new businesses getting off the ground and the often gradual expansion of young and existing businesses in an improving economy.34

The state’s role in promoting economic development should primarily focus on consistent and long-term investment in the fundamentals of creating thriving communities and supporting economic growth within those communities: a good education system, a modern infrastructure, and other community supports and amenities leading to a high quality of life.35 Rather than providing the resources necessary to make these crucial investments, the strategy of providing tax breaks to spur economic development only weakens a state’s ability to make these investments by draining away tax dollars. For the small share of new jobs coming from businesses choosing among multiple geographic options, decisions are much more likely to be made based on proximity to suppliers and markets, worker skills, sufficient infrastructure and quality of life than any tax breaks provided.36

And in the case of RTW, rigorous research that controls for other factors affecting employment finds no connection between a state becoming RTW and job growth. While most states became RTW many decades ago, Oklahoma passed such a law in 2001, which provides a recent example where enough time has passed for valid analysis to be conducted. A subsequent study found no link between RTW and job growth in Oklahoma.37 The University of Kentucky Center for Business and Economic Research also found no relationship between RTW and employment growth in a 2008 report analyzing the economy of southern states.38 There is strong evidence, however, that RTW results in lower wages for both union and non-union workers.39

Kentucky’s Job Growth Has Weakened, Not Accelerated

The inconsistency between press releases claiming soaring business investment and real economic conditions on the ground can be seen in official job growth data. Such data, provided on a regular basis by statistical agencies like the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), provide a much more accurate picture of economic conditions. Recent trends in Kentucky suggest that job growth is not accelerating, and may in fact be slowing down. It is unclear what exactly is behind Kentucky’s recent modest job growth trends, and it takes time to accumulate enough data for rigorous research about the impacts of particular policy changes. But it is false to claim Kentucky is now experiencing a faster pace of job growth.

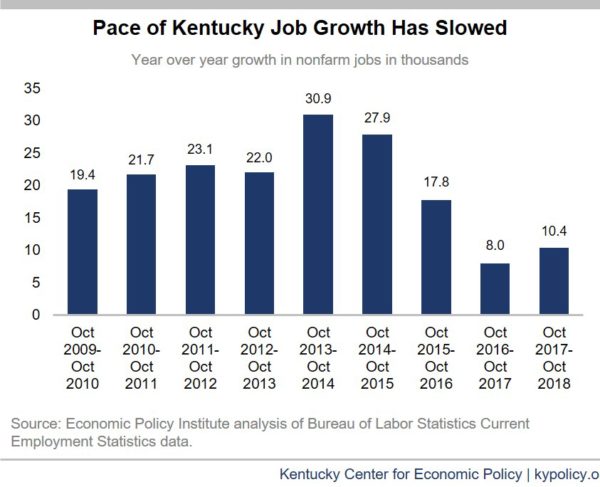

For instance, there has been a slowdown in monthly Kentucky job growth reported by BLS. In the 21 months since January 2017, when the RTW law passed, the state has averaged 700 net new jobs a month. That contrasts with an average of 2,100 net new jobs in the 21 months before RTW passed. In general, the pace of job growth has slowed compared to where it was earlier in the recovery that began in 2010, as seen in the graph below.

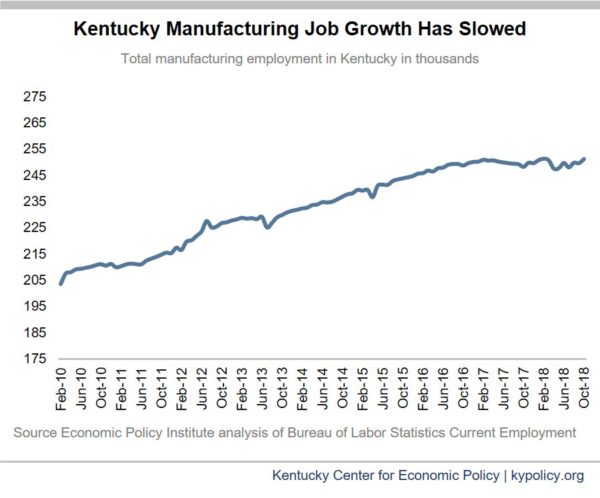

The same flattening can be seen in manufacturing jobs, which are often the focus of recruitment efforts. In the 21 months since RTW passed, the state has gained only a net total of 1,000 manufacturing jobs. In contrast, in the 21 months before it passed, Kentucky gained a net 13,600 manufacturing jobs.

One reason actual job growth tells a different, less robust story than suggested by Cabinet announcements is the inclusion of jobs being eliminated. Kentucky still has 60,000 fewer manufacturing jobs than we had at our peak in 2000, or 20 percent fewer factory jobs. The state has also experienced a net job loss since 2010 of 10,800 coal mining jobs due to the market shift to natural gas and renewable energy sources and 8,600 governmental jobs due to state and federal budget cuts.40

Kentucky is also underperforming relative to the region and the nation as a whole. Over the past year, jobs in Kentucky have grown 0.5 percent compared to growth of 1.7 percent for the U.S. as a whole and 2.1 percent for the southern states.41 Since Kentucky’s RTW law passed, jobs have grown 0.8 percent compared to 2.8 percent for the U.S. and 3.1 percent for the South.42

The quality of jobs is also important, and wage growth has been weak to modest, continuing a trend of stagnant wages for typical workers over most of the last few decades. Since 2009, Kentucky’s inflation-adjusted median wage has increased only 0.4 percent per year on average, and is only 4 percent higher than it was in 1979. From 2015 to 2017, the inflation-adjusted median wage in Kentucky actually fell 0.2 percent.43 Pressure for wage increases should rise as the unemployment rate continues to fall in an economy reaching full employment, but as of yet Kentucky has not experienced sustained, strong wage growth.

Conclusion

It is important for Kentuckians to have the best information available about the state of our economy so we can judge whether particular policies deliver as promised. “Announcements” by the state’s Cabinet for Economic Development of proposed corporate investments paint an incomplete picture of our state economy because they include projects that will create no jobs and ones that may never materialize, give too little attention to job quality, and as of recently ignore facilities that have closed or downsized. In understanding what is really happening with our economy and how people are faring, it is important to rely on official jobs data from statistical agencies and rigorous research about what sort of policies drive economic development at the state level.

- Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development, “Kentucky Locations and Expansions Announced/Reported: January-October 2018,” Nov. 9, 2018, http://www.thinkkentucky.com/kyedc/kpdf/New_Expanding_Industry_YTD.pdf?18. ↩

- Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development, “Kentucky Locations and Expansions Announced/Reported: January-December 2017,” Feb. 15, 2018, http://www.thinkkentucky.com/kyedc/pdfs/New_Expanding_Industry_2017.pdf. ↩

- Morgan Watkins, “Bevin Administration Announces Record-Shattering $9.2 Billion in Business Investments for 2017,” Courier-Journal, Jan. 4, 2018, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/2018/01/04/bevin-administration-announces-business-investments/999657001/. ↩

- “Kentucky’s Corporate Investment Hits Record $9.2 Billion in 2017,” Dec. 30, 2017, https://kentucky.gov/Pages/Activity-stream.aspx?n=KentuckyGovernor&prId=564. ↩

- Bill Vlasic, “Toyota to Invest $1.3 Billion in Kentucky Plant,” The New York Times, April 10, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/10/business/toyota-kentucky-plant-investment.html. Cheryl Truman, “Toyota Gets $43.5 Million in Tax Incentives on $1.33 Billion Investment,” Lexington Herald-Leader, April 10, 2017, https://www.kentucky.com/news/business/article143755074.html. Marcus Green, “Toyota to Make $1.33 Billion Investment at Georgetown, KY. Plant,” WDRB, April 10, 2017, http://www.wdrb.com/story/35109523/toyota-announcing-record-133-billion-investment-in-georgetown-ky-plant?clienttype=generic&mobilecgbypass. Bruce Schreiner, “Toyota Announces $1.33 Billion Investment in Kentucky Plant,” Associated Press, April 10, 2017, https://wfpl.org/toyota-announces-1-33-billion-investment-kentucky-plant/. Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development, “Toyota Reborn: $1.33 Billion Investment in Georgetown Plans Will Keep It Cutting Edge,” April 10, 2017, https://kentucky.gov/Pages/Activity-stream.aspx?n=KentuckyGovernor&prId=334. KEDFA Special Board Meeting, April 5, 2017, http://thinkkentucky.com/kyedc/pdfs/KEDFA_BOOKS/04102017_KEDFA_BOOK_Special.pdf. ↩

- Grace Schneider, “Ford Will Sink $900 Million in Kentucky Truck Plant for New Lincoln Navigator, Expedition,” Courier-Journal, June 20, 2017, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/money/companies/2017/06/20/ford-sink-900-million-louisvilles-kentucky-truck-plant-new-lincoln-navigator-expedition/410520001/. The Lane Report, “Ford to Invest $900 Million in Kentucky Truck Plant, Secure 1,000 Jobs,” June 20, 2017, https://www.lanereport.com/78669/2017/06/ford-to-invest-900-million-in-kentucky-truck-plant-secure-1000-jobs/. Jessica Bard, “Ford Announces Planned $900 Million Investment in Kentucky Truck Plant,” June 20, 2017, http://www.wdrb.com/story/35704941/ford-announces-planned-900-million-investment-in-kentucky-truck-plant. ↩

- Morgan Watkins, “Braidy Industries Still Lacks Financing for Kentucky Mill Construction,” Courier-Journal, Oct. 19, 2018, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/2018/09/20/braidy-industries-financial-filings-aluminum-mill-lacks-financing/1366453002/. ↩

- Morgan Watkins, “ Bevin “Unbelievably Confident” in State-Funded Braidy Industries CEO with Mixed Record,” Courier-Journal, April 5, 2018, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/2018/03/18/bevin-unbelievably-confident-kentucky-mill-builder/948025001/. ↩

- http://www.thinkkentucky.com/KYEDC/BusDirectories.aspx. ↩

- Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development, “Known Business/Industry Facility Closings in Kentucky, January-December 2015,” Jan. 7, 2016, http://www.thinkkentucky.com/kyedc/kpdf/Facility_Closings_2015YTD.pdf. ↩

- Kentucky Career Center, “Warn Notices by Year,” https://kcc.ky.gov/Pages/News.aspx. ↩

- Cheryl Truman, “After 55 Years, Trane Is Closing Lexington Plant, Laying Off 600 Hourly Workers,” Lexington Herald-Leader, Oct. 4, 2018, https://www.kentucky.com/news/business/article219500765.html. Cheryl Truman, “Versailles Plant Closing. Here’s How Many Will Lose Their Jobs, and When,” Lexington Herald-Leader, December 4, 2018, https://www.kentucky.com/news/business/article222612725.html. ↩

- Ford has been manufacturing cars in Louisville since 1913, and Toyota since 1988. Commonwealth of Kentucky, “Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017,” Dec. 13, 2017, https://finance.ky.gov/Office%20of%20the%20Controller/ControllerDocuments/2017%20CAFR.pdf. ↩

- Amazon, “Amazon, “Investing in the U. S.,” https://www.aboutamazon.com/investing-in-the-u-s. Avalara, “Amazon Fulfillment Center Locations,” https://www.avalara.com/trustfile/en/resources/amazon-warehouse-locations.html. ↩

- Commonwealth of Kentucky, “Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017.” “Amazon to Create 2,000 Jobs at New Air Cargo Hub in Kentucky,” Jan. 31, 2017, https://press.aboutamazon.com/news-releases/news-release-details/amazon-create-2000-jobs-new-air-cargo-hub-kentucky. ↩

- Chris Weller, “7 Insane Facts that Reveal How Big Amazon Has Become,” Business Insider, Sept. 7, 2017, https://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-size-insane-facts-about-company-2017-9. ↩

- It is only possible for state tax policies to have a modest impact on those decisions. That can be seen in Amazon’s recent decision to locate secondary headquarters in the New York City and Washington, D.C. areas after Amazon created a national bidding competition in which it named 20 cities as finalists. In the end, it picked the two areas that arguably had the best access to skilled workers and needed infrastructure. Alex Shephard, “Amazon Scammed America’s Hurting Cities,” The New Republic, November 12, 2018, https://newrepublic.com/article/152190/amazon-scammed-americas-hurting-cities. ↩

- “Amazon to Create 2,000 Jobs at New Air Cargo Hub in Kentucky.” ↩

- Greg Paeth, “Amazon Fulfills Kentucky’s Goal to Be World’s Logistics Leader,” The Lane Report, April 7, 2017, https://www.lanereport.com/75668/2017/04/amazon-fulfills-kentuckys-goal-to-be-worlds-logistics-leader/. ↩

- HB1 17RS, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/17rs/HB1.htm. ↩

- “Amazon to Create 2,000 Jobs at New Air Cargo Hub in Kentucky.” ↩

- Amazon press release archive, https://press.aboutamazon.com/press-releases?a9d908dd_year%5Bvalue%5D=2017&op=Year+Filter&a9d908dd_widget_id=a9d908dd&form_build_id=form-Lfn4MutRUxUOFUehQxEPK1jBkwBjvk_UmNeKTjwRH50&form_id=widget_form_base. ↩

- Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development, “Just the Facts: Kentucky Business Investment (KBI) Program, June 2018, http://thinkkentucky.com/kyedc/pdfs/KBIFactSheet.pdf?74. Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development, Kentucky Business Investment Program Enhanced Incentive Counties (2018-2019), http://thinkkentucky.com/kyedc/pdfs/KBIEnhancedCounties.pdf?74. ↩

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “2018 Minimum Wage by State,” July 1, 2018, http://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/state-minimum-wage-chart.aspx#Table. ↩

- Kaiser Family Foundation, “2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey,” Oct. 3, 2018, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey/. ↩

- Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data. ↩

- Cabinet for Economic Development, “Financial Incentives,” http://thinkkentucky.com/Locating_Expanding/Financial_Incentives.aspx. ↩

- Kentucky Financial Incentives Database, http://www.thinkkentucky.com/fireports/fiintro.aspx. ↩

- William Hoyt, Christopher Jepsen and Kenneth R. Troske, “An Examination of Incentives to Attract and Retain Businesses in Kentucky,” Center for Business and Economic Research, University of Kentucky, Jan. 18, 2007, https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=cber_researchreports. ↩

- Anderson Economic Group, “Review of Kentucky’s Economic Development Incentives,” June 11, 2012, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/Lrcpubs/AEG%20KY%20Incentive%20Report_jun112012.pdf. Jason Bailey, “Report’s Findings Suggest Kentucky’s Business Tax Incentives Not Very Cost-Effective Way to Create Jobs,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 19, 2012, https://kypolicy.org/reports-findings-suggest-kentuckys-business-tax-incentives-cost-effective-way-create-jobs/. ↩

- Timothy Bartik, “’But For” Percentages for Economic Development Incentives: What Percentage Estimates Are Plausible Based on the Research Literature,” Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2018, https://research.upjohn.org/up_workingpapers/289/. Peter Fisher, “The Real Path to State Prosperity,” Grading the States, https://www.gradingstates.org/the-real-path-to-state-prosperity/. ↩

- HB368 17RS, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/17rs/HB368.htm. ↩

- Morgan Watkins, “Braidy Industries Mill Scores Another $4 Million in Government Support,” Courier-Journal, Oct. 19, 2018, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/2018/10/19/braidy-industries-mill-gets-4-m-government-grant/1684924002/. Chris Otts, “Kentucky Taxpayers’ Share of Aluminum Plant Company Will Shrink Over Time, CEO Says,” WDRB, Nov. 9, 2017, http://www.wdrb.com/story/36807671/kentucky-taxpayers-share-of-aluminum-plant-company-will-shrink-over-time-ceo-says. ↩

- Michael Mazerov and Michael Leachman, “State Job Creation Strategies Often Off Base,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Feb. 3, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-job-creation-strategies-often-off-base. For Kentucky, the study showed 84 percent of jobs are home-grown, 13 percent are from companies branching into the state and 3 percent are from jobs relocating from elsewhere. ↩

- A summary of the literature with references is available here: https://www.gradingstates.org/the-real-path-to-state-prosperity/. ↩

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Taxes and Economic Development,” ITEP Guide to Fair State and Local Taxes, https://itep.org//www/wp-content/uploads/guide8.pdf. ↩

- Gordon Lafer and Sylvia Allegretto, “Does ‘Right-to-Work Create Jobs? Answers from Oklahoma,” Economic Policy Institute, Feb. 28, 2011, https://www.epi.org/publication/bp300/. ↩

- Christopher Jepsen, Kenneth Sanford, and Kenneth Troske, “Economic Growth in Kentucky: Why Does Kentucky Lag Behind the Rest of the South?,” Center for Business and Economic Research, University of Kentucky, January 2008, https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cber_researchreports/14/. ↩

- Anna Baumann, “What the Research Says About “Right-to-Work” Laws, Employment and Wages,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, April 15, 2015, https://kypolicy.org/what-the-research-says-about-right-to-work-laws-employment-and-wages/. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “The State of Working Kentucky 2018,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 28, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/the-state-of-working-kentucky-2018/. Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, “Kentucky Quarterly Coal Report, July to September 2018,” Nov. 7, 2018, http://energy.ky.gov/Coal%20Facts%20Library/Kentucky%20Quarterly%20Coal%20Report%20(Q3-2018).pdf. ↩

- Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics data. ↩

- Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics data. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “The State of Working Kentucky 2018.” ↩