The severe economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic spells trouble for Kentucky’s budget. The state’s resources were already tight before the virus, but the resulting economic collapse will be a big hit to tax receipts while driving up state costs — threatening our ability to provide vital services, respond adequately to the public health threat and achieve economic recovery once restrictions are eventually lifted.

Two new federal laws begin to address the added strain state governments are facing, but the extent of the downturn will require ongoing and more aggressive federal aid.

Revenues will fall off a cliff, and costs will rise

The bottom is expected to drop from state revenues in the coming months — the only question is how far they will fall. The state downgraded its revenue forecast based on the unemployment rate reaching 5.8% next fiscal year. Yet a recent Goldman Sachs forecast predicted that U. S. gross domestic product will shrink 34% in the second quarter of the year (annualized), which translates to an estimated 251,846 jobs lost in Kentucky by the summer and a state unemployment rate of 16.3% — a level unprecedented in modern times. And actual early numbers are worse than that— the state has processed 279,307 unemployment claims in the last 3 weeks.

A resulting fall in spending and wages will drastically reduce sales and income tax receipts (which make up 75% of our General Fund), as the budget director noted in his April 10 release. That will likely make the new, more pessimistic state revenue forecast seem optimistic in hindsight. In addition, the state followed the federal government in moving to July 15 the deadline to file and pay 2019 income taxes, which will result in a delay of approximately $200 million.

Along with revenue declines, expenditures will increase as state agencies directly combat COVID-19 and as more people qualify for Medicaid due to the loss of jobs and income. During the Great Recession, 100,000 more Kentuckians became covered by Medicaid for that reason. Medicaid will also be a major payer of COVID-19 treatment costs since it covers 1.3 million Kentuckians already, many of whom are at risk of serious illness from the disease.

Kentucky is not prepared

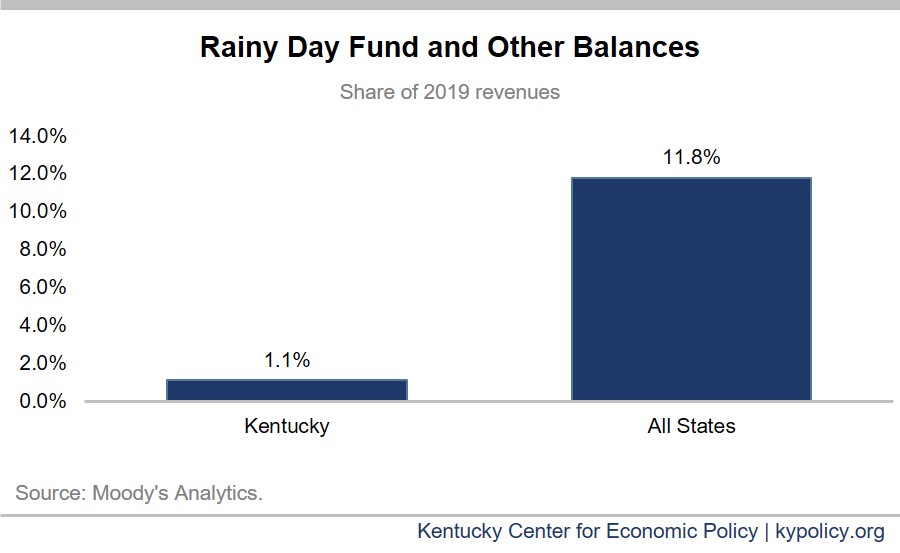

Kentucky is especially unprepared for the shortfall that is coming, first because there is little in our rainy day fund, the purpose of which is to provide resources to weather unexpected revenue shortfalls or increased expenditures.

Kentucky’s rainy day fund is scheduled to reach $306 million in June, or the equivalent of just 10 days of state operating expenses. As a share of the budget, the fund today holds only 10% of what the median state had put aside. According to an economic “stress testing” analysis by Moody’s Analytics, Kentucky ranks 48th among states when it comes to rainy day fund preparedness.

And raising meaningful new state revenue wasn’t part of the budget this legislative session, with the final revenue bill that passed with the budget generating only $5 million. In contrast, during the Great Recession Kentucky raised tobacco and alcohol taxes by over $150 million to help cushion the blow. This time around the state is also phasing in tax cuts from 2018 and 2019 for banks and corporations — cuts that resulted in the worst revenue growth projections in 25 years of consensus forecasting.

Some federal aid is coming, but much more is needed

The federal government has passed two pieces of legislation that provide some help, but much more is needed.

The recently enacted CARES Act will provide the state with $1.599 billion to help address the direct costs of dealing with COVID-19. The new law also includes $409.7 million for K-12 schools and higher education institutions, and monies for child care and other needs.

In addition, the previously passed Families First Act increases the federal share of the cost for traditional Medicaid retroactive to January from its current 72% to approximately 78%. That means about $480 million in state savings on an annual basis, but this assistance ends in the quarter the public health emergency is declared over.

Given the depth of the budget hole we expect to face, this help is not enough. We don’t know how long business closures and other social distancing requirements will be in effect, but it could be a while. And it’s likely that even when these measures begin being lifted, the economy will remain weak as some businesses are unable to reopen, people face debts that were deferred during the crisis and uncertainty about the virus persists.

Federal aid to states is essential to recovery from recessions because state balanced budget requirements limit their ability to respond as aggressively as needed, forcing cuts that put the brakes on economic growth. During the Great Recession, the federal government provided over $3 billion to Kentucky’s budget (much more than what coronavirus assistance has brought in today’s dollars), yet it wasn’t enough to prevent deep state cuts to services. That aid had almost entirely dried up at the beginning of state fiscal year 2012, yet Kentucky’s unemployment rate was still nearly 10% at the time — meaning weak state revenues that forced more budget cuts when the federal assistance went away.

New forecasts say the economic loss from the COVID-19 crisis will likely be worse than the lowest point in the Great Recession. To counteract the harm, Kentucky needs additional, robust federal aid that should be designed to continue automatically until the economy shows evidence it has recovered. A realistic target would be at least another $500 billion— multiple times more aid than was included in the CARES Act— as called for by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Economic Policy Institute and the National Governors Association. There are clear tools the federal government can use, including another sizeable increase in the match for Medicaid costs and flexible grants like were used in the Great Recession.

The state needs Congress to act quickly on the next economic relief bill with those ideas and more included.

Updated April 14, 2020.