A special session this fall will likely include proposals to cut public pension benefits, and new employees are especially vulnerable because their plans can be changed easily under law. However, such cuts do nothing to reduce the existing unfunded pension liability — which is owed to retirees and current employees — and won’t save money over the long-term either. That’s because Kentucky’s pensions are already inexpensive to the state as long as they are properly funded on time.

Actuaries refer to the regular cost of a pension plan as the “normal cost.” The normal cost is the amount that must be contributed each year an employee works so enough dollars are available in the system when employees retire to pay benefits. The remainder of the required payments to a system each year are catch-up contributions to pay for past liabilities where the employer’s payments have fallen behind.

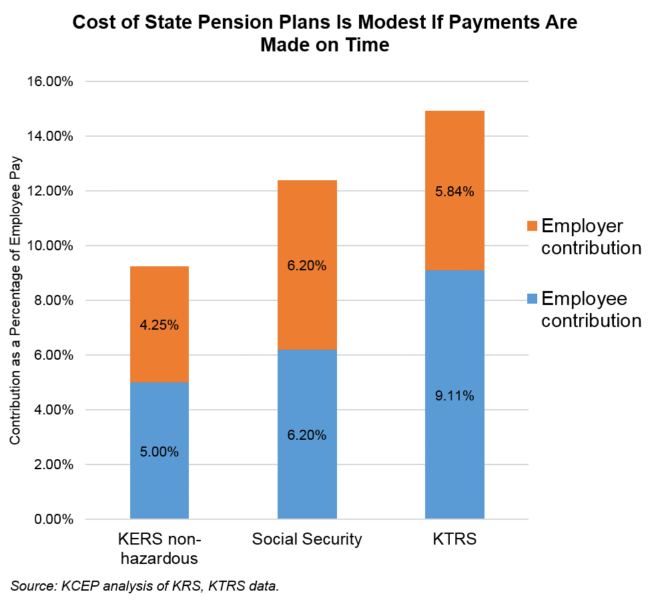

The graph below shows the normal costs as calculated by the pension systems’ actuaries for the state’s two biggest plans, the Kentucky Employees Retirement System (KERS) non-hazardous plan and teachers’ retirement plan. The normal cost for the KERS non-hazardous pension plan is only 9.25 percent of employee’s pay. Of that, the employee contributes the majority by putting in 5 percent, making the employer contribution only 4.25 percent of pay. For teachers, according to the system’s 2016 actuarial valuation, the normal cost is 14.94 percent of pay for new (non-university) members. Again, workers pay the bulk of the cost: employees contribute 9.11 percent and the employer chips in only 5.84 percent.

To put this in perspective, these numbers are similar to the normal cost of Social Security contributions made by and for every worker in the private sector (which state employees also receive but state teachers do not). And remember: on top of their Social Security contribution many private employers make 401k contributions similar in size to the employer contributions below for public pensions in Kentucky.

Normal costs are low in part because defined benefit pension plans are efficient and effective ways to provide a decent and predictable retirement. They especially make sense for governments as a tool to attract and retain skilled workers. As large, permanent employers, governments can build big investment pools that can earn high returns over long periods of time due to low administrative costs and the ability to access a broad set of investments at low fees. Nationally, employers ultimately pay only about 25 percent of the cost of public employees’ pension benefits, with the rest coming from the investment returns the system earns and employee contributions.

Along with defined benefit plans’ efficiency, normal costs are low because Kentucky’s pension benefits are modest. The average non-hazardous state employee receives a pension of only $20,633, and the average teacher receives only $37,368 (and as noted Kentucky teachers do not receive Social Security, which averages $16,320 a year). New workers’ retirements will be even more modest after benefit cuts in 2002 and 2008 for teachers and in 2008 and 2013 for state employees.

Kentucky has a moral and legal obligation to meet the pension promises made to current workers and retirees, and we cannot solve the problem of pension liabilities on the back of new employees either. Current pension contributions are high primarily because Kentucky hasn’t been making adequate contributions in the past, and since the dollars weren’t in the system to earn investment returns the state must now provide large catch-up payments. Further slicing benefits for new employees won’t help — and can even make state costs go up by increasing employee turnover and making it harder to attract and keep qualified workers.