The United States incarcerates 5 times more people per capita than other wealthy countries. Yet, while some states are succeeding at reducing incarceration and its harms to individuals, families and communities, Kentucky’s rate remains 40% higher than the U.S. average.

A new report from the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy explains how, in a context of local fiscal strain, perverse financial incentives for counties to maintain high incarceration and overcrowded jails are preventing progress and harming lives. This cycle derails families and diverts public resources toward incarceration rather than addressing the root causes of challenges in our communities.

Historically, overcrowding in state prisons related to “tough on crime” penalties in the war on drugs led to a 1987 court case requiring the state to pay counties for holding people in state custody. Today, close to half of individuals serving felony sentences for the state do so in county jails, making Kentucky one of just two states in which such a large share of individuals in state custody serve their sentences in local jails.

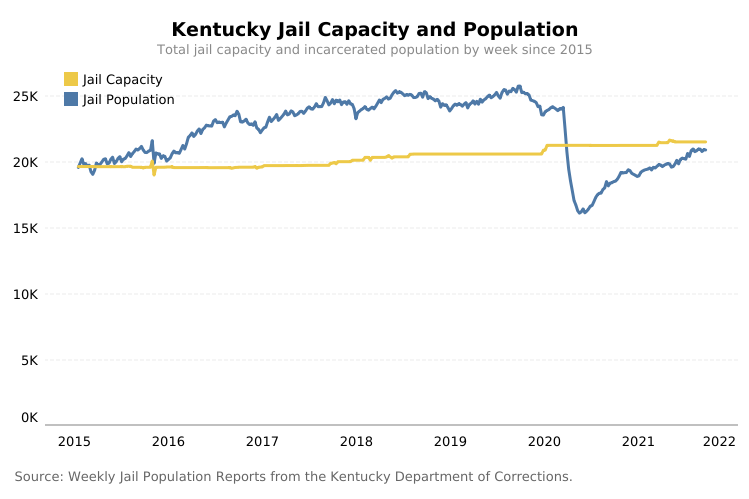

At the same time, Kentuckians who are incarcerated pretrial or on misdemeanor sentences are legally in county custody, with counties’ related costs determined by state laws and funding decisions, as well as separately-elected judges and prosecutors. To offset those costs, counties take on more individuals in state and federal custody, often overcrowding and sometimes expanding jails to house more people.

The report looks at local fiscal strategies related to incarceration as they play out statewide and in five Kentucky counties — Madison, Barren, Leslie, Rowan, and Boyle.

In Madison County, for example, low rates of pretrial release — with the most common, most serious charge for pretrial incarceration being drug possession — contribute to persistent overcrowding, leading the county in 2019 to propose building a costly new jail that included more capacity for holding people in state and federal custody. In other counties like Barren and Leslie, overcrowded jails already house a large share of people in state and federal custody in order to generate revenue and alleviate fiscal pressures.

As part of our report, we spoke with county jailers and other local officials, painting a picture rife with tensions. One jailer shared the opinion, “You can never go too big” with building jails, and the data shows that when bigger jails are built, they are quickly filled. While some local actors advocate for reforms that would reduce pretrial incarceration and counties’ related costs, there is resistance to sentencing reforms that would stem the tide of state incarceration and thus limit revenue options once a county has “gone big” with its jail.

But, we know that incarceration can be safely reduced. We know that local governments need fiscal relief. And we know that more public resources for safe housing, mental health and substance use treatment in communities rather than jails can help put us on a better trajectory.

How do we achieve those goals? Our report concludes with a set of policy solutions that would work together to reduce incarceration and free up resources to achieve greater well-being in Kentucky communities.

- Absent the full elimination of money bail, Kentucky should limit the offenses for which money bonds can be set and create a fast and speedy trial provision. Together, these would reduce pretrial incarceration and related county costs.

- Some felony charges like drug possession should be reduced to misdemeanor sentences, while certain misdemeanor offenses like public intoxication should be decriminalized.

- Criminalizing underlying substance use disorders (SUDs) is not an effective strategy for recovery, and drives mass incarceration in Kentucky. Spending less on incarceration would free up resources for SUD treatment in the community.

- To help stop the wave of jail expansions, the state needs a comprehensive plan to phase out the use of local jails for housing people in state custody that works with counties to identify and alleviate resulting fiscal strains.

- Local governments can do more (and the state can provide financial support) to understand the underlying causes of fiscal strain and overcrowding in county jails and to identify local solutions like reducing if not eliminating money bail. Stakeholders include law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys, incarcerated people and community members.

We have the policy tools we need to alleviate the fiscal pressures driving Kentucky counties to “go big” with jails. When counties balance their budgets with revenue-generating tactics stemming from incarceration, the costs are too high for Kentuckians who are incarcerated, their families and all Kentucky communities. It’s time to disrupt this vicious cycle.

This column ran in the State Journal on Oct. 26, the Northern Kentucky Tribune on Oct. 27, the Courier-Journal on Oct. 28, and the Advocate-Messenger on Oct. 29, 2021.