As we enter the seventh month of the COVID-19 pandemic, jails and prisons have been among the top “hotspots” for COVID-19 at the same time incarcerated individuals are among the most medically vulnerable populations at risk of serious complications from the virus. In Kentucky, in response to these concerns, significant overall declines in incarceration in county jails have occurred, as well as some declines in state prisons.

However, in the past couple of months some local jail populations have increased, particularly in rural counties. With the pandemic stretching on and COVID-19 outbreaks occurring in numerous institutions — and with the recent reopening of courts after a temporary closure — we need to make sure the momentum to reduce incarceration in Kentucky continues and that we do not backtrack. More progress is necessary both to reduce the likelihood of outbreaks and begin reversing the longstanding trend of overincarceration that is too costly to lives, health and our economy.

Overall trend of reducing incarceration has slowed, with some increases in county jails

Jail and prison population reductions have been achieved largely through three rounds of sentence commutations by the governor with a fourth underway, and in response to a series of Supreme Court orders that, among other impacts, increased the number of people released from jail while awaiting trial. Through these orders, administrative release — which is where an individual is automatically released while awaiting trial without being subject to money bail — now includes some felonies (at least temporarily). The issuance of citations rather than the arrest of people who owe fines and fees, which was also ordered by the Supreme Court, is another contributor to jail population declines.

The overall decline in the county jail population in Kentucky remains significant — a decline of 24.1% between the end of February and the end of August. However, in July and August, incarceration in county jails has started to tick back up, with more county jails over capacity. A Vera Institute analysis shows that incarceration in rural Kentucky counties is particularly on the rise.

On February 27, there were 24,071 people incarcerated in Kentucky’s county jails, exceeding the overall capacity of 21,303. On May 14, the lowest point, there were 16,167 individuals housed in the jails. Since then, however, incarceration in county jails has been creeping back up to 18,072 on August 20 — an 11.8% increase compared to mid-May.Higher jail populations — including some jails significantly exceeding 100% of capacity — mean less safe conditions, especially in the context of COVID-19. While the jail population overall is at 84.9% capacity (there were 18,072 individuals incarcerated in county jails on August 20 compared to 21,303 beds total), as of August 20 there were 31 individual county jails over capacity. In contrast, on May 14 when the jail population was at its lowest, only 16 jails were over capacity. Jail overcrowding in Kentucky is a longstanding issue in many Kentucky jails, especially rural ones.

Some counties have had bigger increases in incarceration than others, as shown in the map below. The 5 counties with the largest increases in their jail populations in the last 3 months are Boyle (109.7% increase), Bell (80.4% increase), Hart (75.4% increase), Lincoln (71.9% increase) and Kenton (68.9% increase).

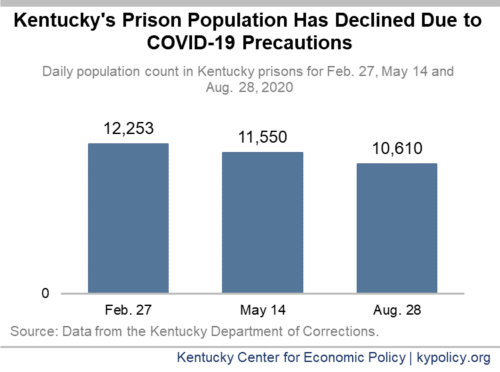

The state’s prison population has continued a steady decline and is now 13.4% lower than it was in late February.

Jail population rise primarily for individuals serving misdemeanor sentences or being held pretrial

People incarcerated in county jails in Kentucky fall into three primary categories — individuals awaiting trial or serving a misdemeanor sentence in county custody, individuals serving Class C or D (the lowest level) felony sentences held for the state Department of Corrections, and individuals in federal custody held by local jails under a contract with the U.S. Marshal or ICE. As shown in the graph below, while the number of people in state custody in county jails has gone down very slightly in the past three months (May 14 to August 20), there has been an increase in the number of individuals in federal custody and a jump of 33.7% in county-level incarceration.

We do not currently have data on the specific drivers of the county-level population increases; it is possible it has to do with shifts in policing and charging practices or with backtracking on provisions to release more people pretrial.

The expansion of administrative release initially led to many more Kentuckians being released pretrial, but that initiative was scaled back some after the initial Supreme Court order. Too many Kentuckians are typically incarcerated while awaiting trial simply because they cannot afford bail. The Administrative Office of the Courts recently testified to a legislative committee that rearrest rates for individuals released pretrial are comparable to the previous year when significantly fewer defendants were released.

In contrast to increases in individuals in county custody, the number of people serving felony sentences in county jails has continued to decline, though the decline has slowed considerably. There were 20% fewer people serving felony sentences in local jails on August 20 compared to late February; however, the decline between mid-May and August 20 was just 1.9%. The decline in the number of individuals serving felony sentences both in county jails and in state prisons is due to sentence commutations by the governor, the fourth round of which is currently in process.

Meanwhile, the number of people in federal custody held in Kentucky’s county jails has increased by 6.6% since late February, with an increase of 9.6% since mid-May.

Status quo is dangerous: Continued efforts needed to reduce prison and jail populations and promote public health

Continued efforts are needed to save more lives, with particular focus on the counties where the jails have once again become severely overcrowded. The scientific consensus is growing about how closed indoor environments with people unmasked and with higher rates of respiratory transmission is consistently a source of outbreaks. Any outbreaks at these facilities put incarcerated people, staff and entire communities at greater risk – especially with jails, where many people cycle through in short periods of time.

In a Prison Policy Institute report released in late June, Kentucky was one of several states that received a D- rating in terms of its response to COVID-19 in its jails and prisons (note: no state scored above a D- rating, indicating how much change is needed nationwide). According to the report, “while some states did more, no state leaders should be content with the steps they’ve taken thus far.” Kentucky did receive top marks for providing and mandating masks (though masks are only required for staff), the announcement of executive orders for release, and up-to-date daily data for state prisons. However, Kentucky received zero points on some metrics, including due to its failure to test asymptomatic individuals (who represent a high number of individual carriers), for not disaggregating data by race and not having an order to halt jail admissions. In addition, larger reductions in incarceration would have contributed to a higher score/grade.

As of September 2, there have been 877 documented COVID-19 cases among individuals incarcerated in state-run prisons in Kentucky, or approximately 8% of the prison population. And 13 incarcerated individuals have died from COVID. There have been 151 staff members test positive in the state-run prisons as of September 2 and 1 reported death thus far. It’s important to keep in mind that institution-wide testing has only occurred when there have been outbreaks rather than before outbreaks occur, the latter of which would enable the spread to be better controlled. The governor noted at a press conference that while testing entire institutions would be more effective, Kentucky does not currently have enough tests to make that possible. However, inadequate testing exists at the same time the general population of Kentucky is being widely encouraged to get tested and on a regular basis.

Despite the fact that almost half of the people held in county jails are serving state sentences, there is no centralized reporting of outbreaks in jails, and each jail sets its own standards and requirements in addressing COVID-19. Thus, the only public information available about COVID-19 infections in jails is through local media coverage. The overall outbreak situation is therefore unknown, but most certainly is worse than can be estimated by simply looking at the prison population. Recent news coverage indicates there have been concerning outbreaks in the Fayette County and Jefferson County jails, for instance.

State needs to reduce incarceration and increase safety for those who remain behind bars

Even as the governor has initiated an important fourth round of commutations, Kentucky needs to employ additional strategies to continue its momentum reducing overcrowded prisons and jails, avoid backtracking and strengthen public health measures to keep people safe:

- There needs to be centralized reporting on COVID testing, positive cases in county jails, and prevention measures being taken. While data on the number of cases in state prisons is publicly reported, county jails do not follow the same reporting protocols even though nearly half of individuals incarcerated in Kentucky’s county jails are actually in state custody.

- County-level data needs to be examined in order to better understand the specific local drivers of incarceration increases.

- The state must increase safety for those who remain incarcerated, including by testing staff and incarcerated people for infection on a widespread basis.

- Jails should reduce the number of, or stop voluntarily accepting, individuals in federal custody.

- Data needs to be collected on the racial breakdown of reductions in incarceration.

- The governor/administration must work to ensure individuals leaving jail are provided with new photo IDs to secure housing and employment and thereby significantly reducing the likelihood of them reentering the criminal legal system.