As unemployment claims surged in Kentucky due to COVID-19 related layoffs, the state’s unemployment insurance (UI) trust fund was quickly exhausted. Kentucky is one of 21 states and territories that have had to borrow money from the federal government to continue paying UI benefits, which is the second time in 15 years the commonwealth has borrowed. Kentucky has needed to borrow, not because our UI benefits are too generous — in fact Kentucky’s benefits are especially hard to qualify for — but because our tax structure is inadequate and outdated.

As a result, we do not build up a sufficient balance during good times to see us through economic downturns. The resulting borrowing ends up costing more in the long run because we have to pay interest on the loans. Borrowing also leads to an increase in federal unemployment taxes while the economy is recovering, creating pressure to cut benefits or use state funds to pay back loans that could go to other, more pressing needs.

The solution to this problem is not to cut our already inadequate benefits further, which will hurt workers, businesses and our economy. Nor is it to cut state UI taxes further or delay modest scheduled tax increases that will occur under existing law. Rather, the solution is to modernize our tax structure so that we impose adequate taxes on a sufficient base to build up a stronger UI trust fund during good times so that we’re better prepared for the next downturn.

Kentucky’s UI tax structure is insufficient

Going into this recession, the inevitability of Kentucky needing to borrow in an economic downturn was clear based on indicators tracked by the U. S. Department of Labor:

- In 2020, Kentucky’s trust fund was ranked 11th worst among states and territories from a solvency standpoint with a rating of 0.57 compared to a minimum level of solvency of 1. The last year Kentucky had a solvency of 1 was 1974. Since we entered this recession, 16 of the 20 states and territories with solvency ratings under 1 have had to borrow from the federal government, while only 5 states and territories of the 30 with ratings above 1 have had to borrow. As of November 27, 21 states and territories have borrowed over $43 billion to continue paying UI benefits during the pandemic. Kentucky has so far borrowed $487 million. In comparison, during the Great Recession, 36 states and territories borrowed more than $47 billion with Kentucky borrowing $972 million.

- According to a 2019 report that compares current average state UI tax rates to a rate than would be necessary for a minimum adequate level of financing, Kentucky’s rate of 1.76% would need to be 2.56% — a 31% difference. Kentucky’s differential between what is imposed and what is needed is the 9th worst among all states and territories.

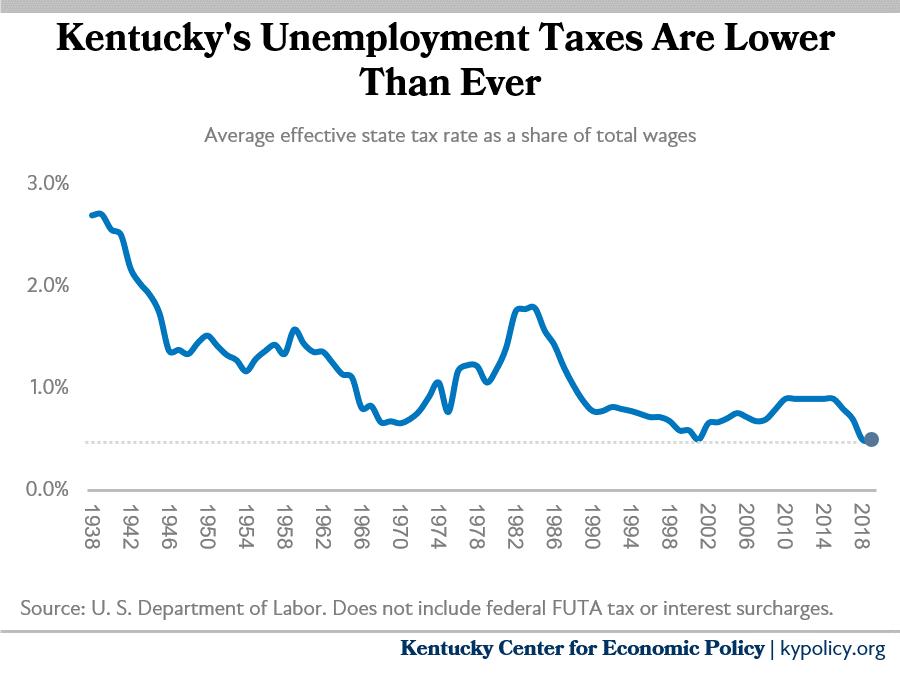

Kentucky’s indicators are poor because the state’s UI tax system is outdated and insufficient to generate the revenue needed to prepare for downturns. The state’s effective tax rate is at the lowest level in its history, in part because it applies to a much smaller share of wages than it once did. Neither the wage base nor the tax rates have been adjusted to keep up with changing economic conditions.

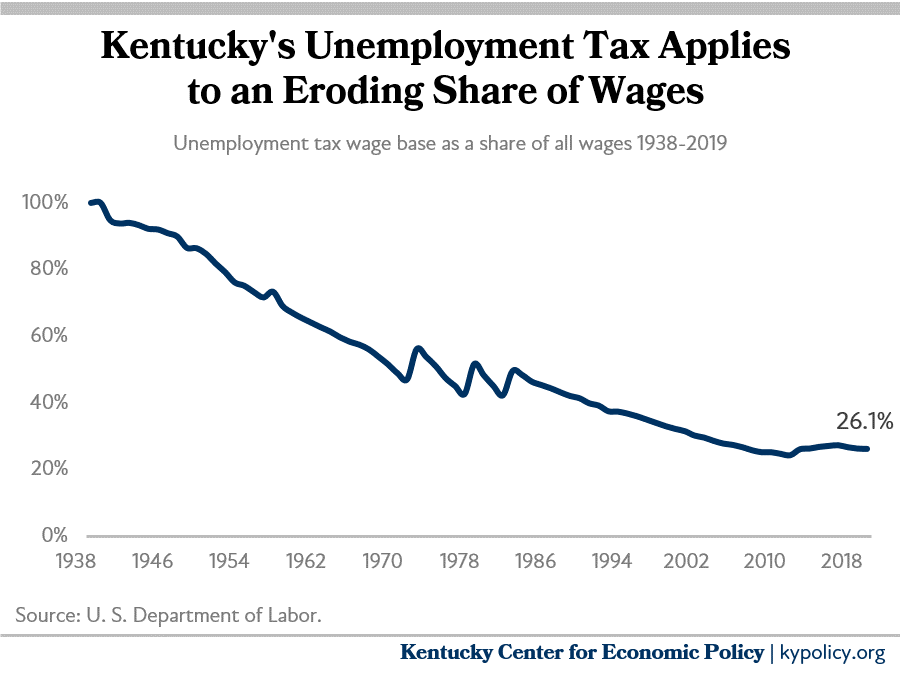

The taxable wage base is the maximum amount of earned income for each employee that an employer must pay taxes on — any amount of wages and salaries paid over the taxable wage base is not subject to the tax. In 2019, Kentucky had a relatively low taxable wage base at $10,500 (set to go to $12,000 by 2022 due to changes the legislature made in 2010). This means the tax applied to only 26% of total wages, a share that has steadily declined since applying to 100% of total wages when the program began in 1938, as illustrated below. When the taxable wage base does not keep up with growth in wages, it limits how much is collected in taxes compared to what is paid in benefits, which is calculated as a percentage of a laid-off employee’s prior wages.

This taxable wage base is also low compared to other states. While Kentucky’s was $10,500 in 2019, the U. S. average was $18,526, or 76% higher. A total of 35 other states apply the tax to a larger base, including 18 states in which businesses pay the tax on more than $25,000 in wages per employee.

Besides the taxable wage base, the other factor that contributes to the solvency and adequacy of a UI tax system is the rate at which employers pay, which is determined by a combination of the size of the state’s trust fund balance and the experience rating of the employer (essentially, their past history of employee layoffs). The combined effect of the eroding taxable wage base and low tax rates is reflected in UI taxes as a share of total wages. This ratio was lower in 2019 than it has ever been going back to 1938 when the program was created, as shown in the graph below. The average UI tax rate as a share of total wages was down to only 0.46% of total wages in 2019, and so far in 2020 the average tax rate has fallen to 0.39% of total wages. Many employers pay the tax at very low levels — 79% of total wages paid are by employers with effective tax rates below 0.5% compared to a 68% U. S. average. Even after the increase that will come in January because the state has borrowed money from the federal government in the current recession, the state’s average UI tax rate will remain lower than it has been approximately 82% of the time over the entire history of the program.

Kentucky’s benefits are not the problem

The problem is not that Kentucky’s benefits are too generous — in fact they are very modest. In 2019, benefits paid under our UI program replaced just over half (50.8%) of lost wages on average. As of September 2020, Kentucky had an average benefit of only $281 a week or $1,204 a month — lower than the national average and 35 other states. The minimum benefit is only $39 per week or $168 per month. Compared to the amount needed for a basic standard of living, these benefits come up far short. For example, a two-parent, two-child household in Mercer County needs to earn an estimated $5,487 per month for a “modest but adequate standard of living” according to the Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator. The inadequacy of regular benefits is one of the reasons that the federal government provided supplemental benefits during the current downturn.

In addition to benefits being modest, they are difficult to access. In 2019, fewer than 1 in 5 (19.5%) unemployed Kentucky workers — as determined monthly by the Current Population Survey — qualified for benefits, which was far lower than the national average of 27.7%. There are several reasons for Kentucky’s limited access, including the way we determine eligibility, which excludes many part-time, low-wage and temporary workers; the narrowness of the circumstances under which a person lost his or her job; and that fact that unlike many states, Kentucky does not allow benefits to be used to reduce hours while keeping people employed (a concept referred to as “work sharing”). The restrictions are especially likely to impact women and Black workers, because family roles, care responsibilities and discriminatory practices are more likely to result in sporadic work histories and employment patterns.

2010 changes hurt workers and did not result in an adequate tax system

The last time Kentucky borrowed funds, during the Great Recession, the 2010 General Assembly enacted legislation to help pay back that loan that included both modest tax increases for employers and significant benefit cuts for employees. But while the employee benefit cut was made permanent, the tax increases were not indexed to maintain their effectiveness over time.

That legislation cut the size of benefits permanently by 8.8%, while also requiring a “waiting week” before receiving benefits and slowing the growth of the maximum benefit. The major changes on the tax side involved increasing the taxable wage base from just $8,000 at the time to $12,000 by 2022 and increasing the trust fund balance levels below which a higher tax rate is paid. While these tax changes were an improvement, their effect will erode over time because they were not indexed to inflation. As shown in the first graph above, the increase in the taxable wage base has only been enough to stop but not reverse its erosion as a share of total wages. The erosion will resume after 2022.

Kentucky must protect workers and the economy — and prepare for the next recession

Because the state borrowed funds in this recession, there will be a very small increase in employer contributions going into effect in January. Yet even with the modest UI tax increase, Kentucky’s UI taxes will remain very low. In effect, the bump equals only 0.05% of business sales on average. There will be even smaller interest payments that begin in September of 2021 and federal tax credit reductions that will begin after November of 2022 to repay the principal of the loan.

Recently, the governor has indicated the use of valuable CARES Act funds, which must be expended by December 31, 2020, to reduce the trust fund loan amount. But these limited funds are needed for very real and pressing crises Kentuckians are facing — including rent and utility debt, the threat of homelessness and trouble providing food and other basic needs.

It’s imperative that we plan better for the next recession. Going forward, policymakers should avoid measures that diminish existing tax provisions or delay the implementation of a very modest series of scheduled short-term increases in employer taxes. And it would be harmful to workers, their families and our economy to further compromise the effectiveness of the UI system by cutting already inadequate benefits.

A proactive plan, on the other hand, would create a UI tax structure that keeps up with the economy through an increased and indexed taxable wage base, and a rate schedule that correlates rate reductions to increased and updated solvency targets as established by the Department of Labor. Recessions have happened before and will happen again. Given the importance of the UI program in providing support to laid-off workers while propping up our economy during economic downturns, it is vitally important that choices be made to ensure that both benefits and revenues remain sufficient to adequately serve these important purposes. Failure to do so is both short-sighted and costly to all Kentuckians.