Advocates for criminal justice reform in Kentucky hope to see effective and much-needed bail reform in the upcoming legislative session. But without other changes focused on reducing the number of Kentuckians in prison as other states have made, Kentucky will likely continue along the path of a growing incarceration rate. This growth costs the state money, permanently harms Kentuckians’ lives and has a disproportionate impact on persons of color.

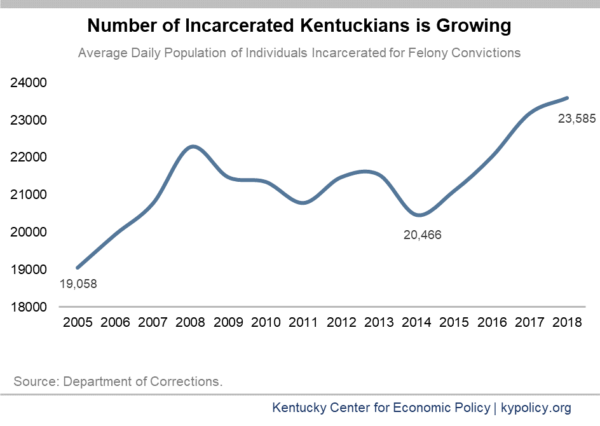

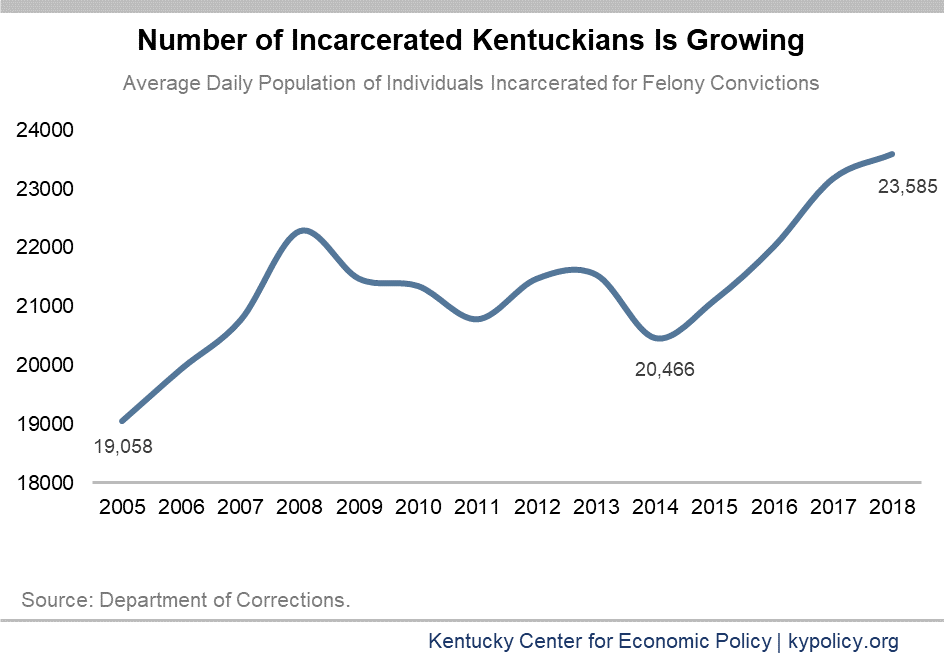

Many states have successfully implemented significant justice system reforms over the past decade, reducing the number of people incarcerated as well as state expenditures. In contrast, between 2007 and 2018 in Kentucky the number incarcerated for a felony conviction grew by 14 percent, as shown in the graph below. And this growth happened despite criminal justice reforms enacted by Kentucky in 2011. Between 2015 and 2016, Kentucky had the second-highest percent increase among states in the number of people incarcerated.

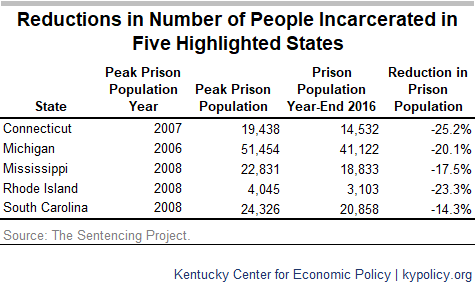

A recent report from the Sentencing Project details how five states that have instituted reforms – Connecticut, Michigan, Mississippi, Rhode Island and South Carolina – have achieved substantial reductions in the number of people in prison over the past decade, while also experiencing declining crime rates. The table below shows the reductions in incarceration, ranging from 14.3 percent in South Carolina (between 2008 and 2016) to 25.2 percent in Connecticut (between 2007 and 2016).

At the national level — and specifically in Kentucky as well — persons of color are overrepresented throughout every aspect of the criminal justice system. While the reforms highlighted in the report have in some cases led to modest reductions in these disparities, much more progress is needed in this area.

Reforms Led to Closure of Facilities and Savings to the States – While Crime Declined

Other states’ advances are allowing them to close facilities, even as Kentucky is having to reopen a previously-shuttered private prison to handle its growing population. For example, Michigan closed and consolidated more than 26 prison facilities and corrections camps between 2006 and 2016 with the cost savings so far amounting to $392 million. Similarly, South Carolina closed 7 correctional facilities and achieved real savings of $33 million in operating costs.

Dispelling the concern that such reforms lead to more crime, the index crime rate – including both violent and property crimes— went down in all 5 states identified in the report: a 5 percent decline in Mississippi, 25 percent in South Carolina, 27 percent in Connecticut, 31 percent in Rhode Island and 37 percent in Michigan. While declining crime rates did account for some of states’ reductions in incarceration, they were only a small part. And reduced crime rates do not always translate into fewer people incarcerated, as can be seen in Kentucky, where nonviolent crime has been declining but felony indictments, particularly for non-violent low-level (Class D) offenses, have been going up.

What Criminal Justice Reforms Are Working – and Needed in Kentucky?

What has worked in other states can provide important lessons for Kentucky.

Reductions/Adjustments in Criminal Penalties

States’ sentencing reforms are having a big impact:

- Connecticut eliminated mandatory minimum sentences and reclassified nonviolent drug possession crimes as misdemeanors, among other policy changes. The modest reduction in racial disparities seen in the state’s justice system are in part due to these sentencing changes.

- Mississippi scaled back policies for nonviolent offenses that required 85 percent of time be served (and applied changes retroactively); the resulting increase in parole accounted for two-thirds of the decline in the number of people incarcerated. The state also created graduated sanctions for felony property offenses and drug offenses, which led to fewer and shorter prison terms. There was some reduction in racial disparities as a byproduct of these reforms.

- Rhode Island achieved a 59 percent decrease in new court cases for drug crimes by eliminating mandatory minimum sentences for all drug crimes and changing possession of small amounts of marijuana to a civil infraction.

- South Carolina eliminated mandatory sentencing for drug possession crimes, expanded alternatives to incarceration for drug offenses and equalized sentences for crack and powder cocaine. In addition, the state reduced penalties for many property crimes to misdemeanors by doubling the dollar amount that had previously triggered felony charges; the maximum sentence for non-aggravated burglary was also reduced by a third. The felony dollar threshold reform was not found to increase property crime, and the number of people sentenced to prison for property crime declined by 15 percent. These reforms contributed to modest improvements in racial disparities in South Carolina’s criminal justice system.

Kentucky did decrease penalties for some drug crimes with the state’s 2011 reforms in HB 463, the Public Safety and Offender Accountability Act, but has since reversed some reforms. Among other drug policy changes, HB 463 reduced criminal penalties for low-level drug trafficking based on an understanding that Kentuckians struggling with addiction often share drugs or sell small quantities to support their own habits. However, in 2017 the state reversed these reforms for heroin with the passage of HB 333, which increased sentences substantially for “trafficking” in even small amounts. According to one estimate, HB 333 will account for 40 percent of the projected growth in the number of Kentuckians in prison over the next decade.

In addition, Kentucky has low felony thresholds for a number of low-level crimes including theft, and drug possession (other than for marijuana) remains a felony offense.

Fewer People Entering Prison Due to Failure on Community Supervision

States are also addressing the problem of people being incarcerated for minor violations while on community supervision (i.e., probation or parole). These violations are often technical in nature, involving infractions like missing an appointment with a parole officer or failing to successfully complete substance use disorder treatment. National research indicates there may be additional barriers to successful probation and parole for people of color including due to a lack of supervision supports and evidence that probation and parole officers may penalize people of color more harshly than whites for the same behaviors.

Several of the states highlighted in the report are reducing the number of people going to prison due to such violations through targeted systems reforms. Michigan’s changes to parole and probation have led to fewer people being incarcerated or reincarcerated, accounting for nearly a third of the decline in the number of people in prison. The range of graduated sanctions available to parole agents was increased and the severity of the sanction was tied to the seriousness of the violation. For more consequential or repeated violations, individuals were placed for no more than 120 days (typically 30 to 90 days) in technical rule violator centers. Returns to prison in Michigan fell by 41 percent through 2016.

In Kentucky, while HB 463 included graduated sanctions for those on community supervision, many judges used their discretion to ignore the law because they disagreed with it. The number of Kentuckians being incarcerated for violating parole has even been on the rise, with increases occurring for drug and property offenses in particular. In 2016, 61 percent of the people entering jail/prison were previously on supervision. Of that population, 96 percent of parole revocations were for technical violations resulting in an average 11 months in custody. And those serving time for probation revocation for the lowest level (Class D) felony offenses receive longer sentences than those sent straight to jail for the same offenses — nine months longer, for example, in the case of drug possession.

Expanded Initiatives to Overcome Barriers to the Feasibility of Release

States are also having success in overcoming common barriers to being released on parole, including for those who have been determined to be “low risk” and nonviolent:

- Connecticut restructured parole processing, which led to 15 percent of the overall decline in the number of people in prison since 2007. As part of these changes, parole hearings were expedited for nonviolent offenses.

- Michigan increased the parole approval rate from 47 percent in 2000 to 72 percent in 2016. A key strategy was temporarily increasing the number of parole board members to enable consideration of those who had served their minimum sentence for a nonviolent crime. Restrictions were also placed on further parole denials for this group as long as risk assessment scoring did not indicate they were a high risk.

- In Mississippi, an increase in the number of people being released on parole accounted for about two-thirds of the reduction in the overall number of people in prison. A 2009 reform shortened the time to parole consideration for nonviolent convictions, changes that were applied retroactively. And a 2014 law further expanded eligibility for consideration of parole, including for certain individuals age 60 and over; it also created a presumption of parole for particular crimes absent certain circumstances.

Kentucky’s parole rates have been much lower than expected when HB 463 was passed. In 2016 only 41 percent of incarcerated Kentuckians eligible for parole were released. Many of the individuals who are denied parole are considered to be “low risk.”

Lessons for Kentucky

Additional Sentencing Reforms Needed

In addition to reversing HB 333’s penalty increases for low-level heroin trafficking, Kentucky should raise the felony theft threshold from $500 (roughly the cost of a cell phone) and drug possession should be classified as a misdemeanor, which many other states — including Tennessee and South Carolina (highlighted in the Sentencing Project report) — already do.

Sentences for Probation and Parole Violations Should Be Limited

The revocation of community supervision is a major driver of the growing number of Kentuckians who are locked up. The state should amend the law to limit the length of time a person on probation or parole can be incarcerated for a technical violation. The following limits were proposed in HB 396:

- For the 1st revocation, up to 30 days.

- For the 2nd revocation, up to 90 days.

- For the 3rd revocation, up to 180 days.

- For the 4th and any subsequent revocation, up to two years.

Kentucky Needs to Streamline Parole Process

Most people sent to prison are eligible for parole at some point during their sentence, but parole release rates in Kentucky have been dropping since 2013. Parole is particularly underutilized for those incarcerated for low-level offenses, in part due to the limited time and resources of the parole board.

HB 396 would have established an administrative parole process that allows Kentuckians serving a sentence for a Class C or D (the lowest level) felony offense that is not a violent or sexual offense to be released at their parole eligibility date without a hearing in most cases.

Continuing to Increase Penalties Undermines Reforms

The Sentencing Project report emphasizes that enhancing penalties for violent offenses reduces the impact of sentencing reforms — and notes ”research has documented that enhancing already harsh sentences adds little crime deterrent effect and produces diminishing returns for incapacitation effects.”

Even as Kentucky has taken some steps forward with criminal justice reform in recent years — including felony expungement in 2016 and a first-step reentry bill in 2017 — the state has also taken some big steps backward by increasing criminal penalties, typically in ways that are not backed by evidence as reducing crime or increasing public safety. In the 2018 General Assembly alone, according to an interim presentation by the state’s Public Advocate, there were 26 provisions enacted that increased sentences or established new crimes (including the wrongheaded “gang bill” HB 169) — and on the other side, just two provisions were enacted that eliminated crimes or reduced sentences.

Specific Focus on Reducing Racial Disparities Needed

Criminal justice reforms should also reduce racial disparities throughout state systems. The report found that Connecticut, Mississippi and South Carolina did see modest reductions in racial disparities as a byproduct of reforms; however, the report recommends that in order to achieve more meaningful change states need to explicitly identify reductions in racial disparities as a policy goal.

Kentucky should take note given the considerable racial disparities in incarceration in our state. Without such a focus, inequities can remain, as in New Jersey where there has been a significant decline in the number of people incarcerated but the state has the largest racial disparities in the nation — and disparities may even grow such as with Kentucky’s juvenile justice reforms.