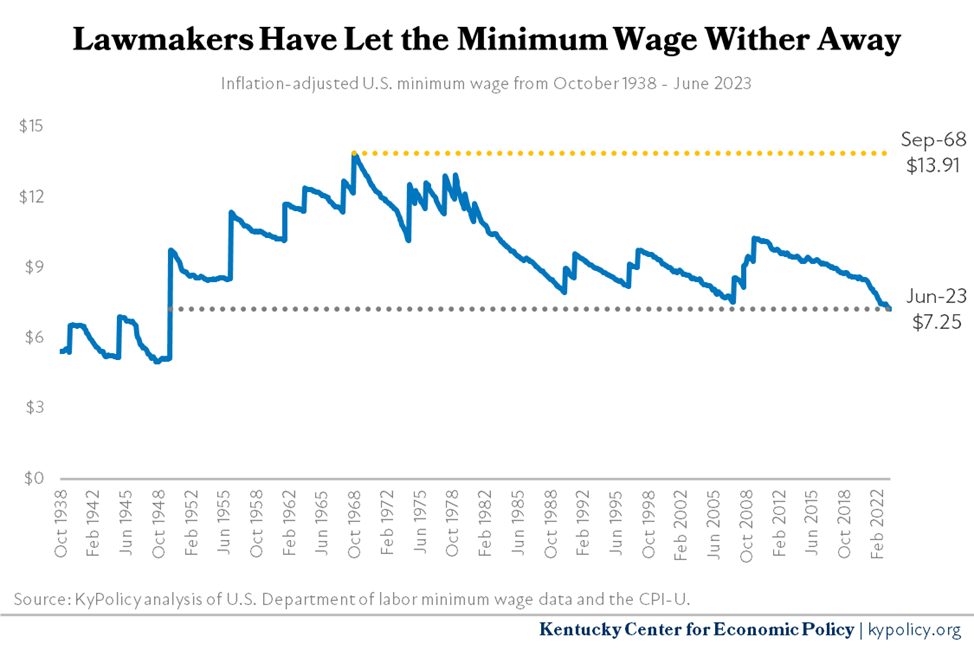

Today marks 14 years since the federal minimum wage increased from $6.55 an hour to $7.25. For the dozens of states, including Kentucky, that have failed to boost the minimum wage on their own, it hasn’t moved since. That’s left tens of thousands of people across the commonwealth earning poverty wages as the price of housing, food and other necessities has skyrocketed.

Since July 2009, inflation has reduced the minimum wage’s purchasing power by 40%, making it more and more difficult for people who earn the least to make ends meet. When accounting for the effects of inflation, the minimum wage is now at its lowest point since 1950.

Congress established the minimum wage in 1937 following the Great Depression to ensure “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.” It was meant to ensure a floor through which no worker could fall. But since that time, the floor has collapsed through inaction, with Kentucky workers who are tipped, disabled, incarcerated or living in expensive areas falling even further behind.

Minimum wage is so low it no longer broadly lifts wages

With the minimum wage so low, not many employers can find workers willing to work for it. Yet according to 2021 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (the most recent available) 5,000 Kentuckians still earned $7.25 an hour – though given tight labor markets and rising inflation, that number is likely even smaller now. Contrary to popular misconception, minimum wage workers are not all teenagers. In fact, 56% of people earning the minimum wage are over 24. And they can be found across industries, with a concentration in retail and leisure and hospitality. Additionally, women comprise nearly 7 out of 10 low-paying jobs in Kentucky, while comprising less than half of the overall workforce.

If a minimum wage policy is working, many more workers will make the minimum wage because that shows it is effective in lifting paychecks toward the levels workers need to live. Markets alone are not working to adequately raise wages, as the data shows many Kentucky workers are making too little to support a basic family budget. There are 343,000 Kentucky workers earning less than $15 an hour, leaving one in five workers with too little earnings to support themselves and their families, according to MIT’s cost-of-living calculator. Raising the minimum wage wouldn’t just help those at the bottom of the wage scale. Employers would need to provide raises to prevent “wage compression” for those who currently earn near what a new minimum wage is set to.

Kentucky has the ability to raise the minimum wage above the federal level. Since 2014, 28 states and Washington, D.C. (including 5 out of the 7 states that border Kentucky) have done just that, raising their minimums to as high as $17 an hour. In fact, in 2007, Kentucky set its own minimum wage, but made it was no higher than the federal minimum of $7.25 by 2009. An attempt was made in 2016 to raise it again when a bill filed by the Speaker of the House called for an increase to $10.10. But that bill and others since have failed, and Kentucky has been stuck with a stagnant federal minimum wage.

Some workers earn even less – a “subminimum wage”

In Kentucky, roughly 16,000 workers actually earned below the minimum wage in 2021 for a variety of reasons. Workers who earn tips (a practice that was established during slavery, enshrined during Jim Crow and allowed to continue through inaction), have seen their minimum wage stuck at $2.13 an hour since 1991. While employers are required to make up the difference between the tipped minimum wage and $7.25 if the workers’ tips don’t reach that level, employers often fail to do so, or worse, fail to give the tips to their workers altogether; these are both common wage theft practices. The combination of a radically low base-wage and the susceptibility to wage theft means tipped minimum wage workers are more likely to earn below the poverty line than workers covered by the full minimum wage.

In addition, employers can apply to the U.S. Department of Labor to run a “14(c) program” that allows them to legally pay workers with a disability far less than the minimum wage. A U.S. Government Accountability Office report found that in 2019, most workers covered under this program earned less than $3.50 an hour. Most of these workers had an intellectual or developmental disability. While this is a relatively small population —there were about 122,000 such workers nationally in 2019 — it allows employers to underpay a workforce that is already economically insecure. States can increase or abolish the subminimum wage for disabled workers, as 14 states have done, but Kentucky is not yet one of them.

There is no minimum wage for workers who are incarcerated. The result is that Kentuckians who work while in prison or jail earned between $0.13 and $0.33 per hour in 2017. That can undercut the wages of non-incarcerated workers due to the savings available by employing those in prison or jail. In addition, these paltry wages often never make it to workers’ accounts, but are used to pay the state or county back for various prison-related fines and fees.

The General Assembly doesn’t allow local governments in Kentucky to raise their minimum wage

There are dozens of cities and counties across the country that have opted for a higher minimum wage than what their state or the federal government have set. These are typically areas where the cost of living is higher than the state as a whole, so local governments have sought to support their constituents and local economies by raising the wage floor.

In 2014 and 2015, Louisville and Lexington raised their minimum wages to $9 and $10.10, respectively, to be phased in over several years. In 2016, however, after a lawsuit by the Kentucky Retailers Association, the Supreme Court of Kentucky struck down those ordinances. The ruling states that the General Assembly can act to permit localities to establish a higher minimum wage but, so far, lawmakers have not chosen to do that despite several filed bills.

Kentucky needs a higher minimum wage

July 2019 marked the longest period the U.S. — and Kentucky — has gone without a minimum wage increase since its inception. We are now four years past that point. Recent wage gains resulting from a tight labor market have been the exception to a long history of stagnant income growth, but those gains by themselves are not enough to ensure Kentucky families can make ends meet, and have been largely offset by the recent increase in the cost of living expenses.

Absent congressional action, Kentucky lawmakers can, and should, ensure there is a wage floor that provides for family well-being by substantially raising the minimum wage and ending the practices of subminimum wages for tipped and disabled workers. Additionally, the state should reverse course on preempting local governments from being able to address the higher cost of living through a local minimum wage. We have known these solutions for too long without acting on them – it’s past time we gave Kentucky a raise.