House Bill 7 (HB 7) would implement several harsh measures making it harder to get and keep food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and medical assistance through Medicaid. Together, these changes would lead to tens of thousands of Kentuckians losing vital assistance with groceries, medicine and doctors’ bills — largely by tripping them up with added paperwork requirements. This not only will hurt families and the grocers, farmers markets, hospitals and pharmacies that serve them, but will also weaken local economies, particularly in rural Kentucky, and create many new layers of administrative work for the Cabinet for Health and Family Services (CHFS), slowing down access to all CHFS-administered programs like the Child Care Assistance Program.

For many people, life in Kentucky is not easy. A fourth of jobs pay poverty wages, racial and geographic inequalities are deeply entrenched, half of the state is a child care desert, workers lack paid leave for caregiving and illness, and communities need much more public investment to support economic opportunity and well-being. Therefore it is especially critical that underpaid workers, people facing racial discrimination, caregivers, Kentuckians with disabilities and people living in regions without adequate employment has access to a safety net that helps them make ends meet. An abundance of research shows that’s exactly how the safety net is used: as needed, benefitting well-being along several measures, with enrollment in various programs dropping as economic circumstances improve.

The last thing Kentuckians need is more stress, fear and time away from their families and jobs caused by navigating an increasingly burdensome, complex and punitive benefits system that treats them as a suspect rather than as simply trying to make their lives better. Help with groceries and medicine is a foundation on top of which a family can build a life, but HB 7 puts cracks in that foundation and pushes families back into poverty.

HB 7 puts new paperwork, reporting requirements, red tape and other obstacles between Kentuckians and help with their food and medicine

HB 7 prohibits the state from giving food assistance to certain adults in economically distressed areas, even during downturns.

Non-disabled Kentucky adults who don’t have dependents can receive SNAP benefits while out of a job for only 3 months out of a 36-month period. But recognizing that finding a job during a downturn or in an economically distressed county is difficult, and that SNAP can act as an economic stabilizer, the federal government allows states to waive that time limit. The entire country did this during the Great Recession and then again during the COVID-19 downturn.

But HB 7 would take away the ability of the state to waive time limits, pushing some adults and their households deeper into food insecurity and poverty while harming local economies. During the years Kentucky was recovering from the Great Recession, these waivers expired in most counties, ultimately leading to 34,137 Kentuckians losing food assistance. That lowered the total grocery money available to others who lived in their households and pulled millions out of local economies — creating a ripple effect throughout as $1 spent on SNAP generates nearly $2 in the broader economy. If HB 7 passes, counties in eastern Kentucky will be especially harmed by this ban, as jobs are scarce in those counties and workers there have a harder time finding work than the rest of the state. Now they will have a harder time affording food, too.

HB 7 bans the state from providing exemptions to the SNAP time limit for those in extraordinary circumstances.

For those slated to lose food assistance because of the SNAP time limit for certain jobless adults described above, the state can step in to exempt a limited number of cases when there are extraordinary circumstances. This ensures that when folks hit a bump in life outside their control, their situation isn’t exacerbated by taking away help with groceries as well.

By both banning waivers in areas that are economically distressed, and then also not allowing for individual extenuating circumstances to be considered, HB 7 creates a rigid, one-size-fits-all time limit for jobless Kentuckians seeking help with food. And just like the ban on waivers, this will not only hurt those who have their SNAP benefits revoked, but others in their household, local grocery stores and the broader economy as well.

HB 7 ends Broad Based Categorical Eligibility, creating new barriers to SNAP for seniors and households with kids.

Broad Based Categorical Eligibility (BBCE) allows states to align SNAP asset and income eligibility with that of other programs, like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Removing BBCE brings back the asset test that makes Kentuckians ineligible for food assistance if they have assets valued at more than $2,500 (or $3,750 for a senior or person with a disability). These assets include things like what’s in a checking or savings account, retirement accounts, or even the value of educational loans in repayment. Ending BBCE would also duplicate administrative work, requiring the Department for Community Based Services (DCBS) staff to check assets like bank account balances and car values for all 528,000 Kentuckians that participate in SNAP. This is why only eight states operate without BBCE.

For families, the end of BBCE under HB 7 could mean losing help with groceries because they have a savings account with enough to cover next month’s rent in order for both parents to get to work. Implementing asset tests would also take food assistance from some of the 1 in 6 older adults in Kentucky facing food insecurity who rely on assets and modest savings to get by without an income. HB 7’s harsh asset test is a poverty trap that will force families and seniors to choose between saving for the future or meeting their nutritional needs.

HB 7 creates tripwires for losing food assistance through “change reporting.”

House Bill 7 would make Kentucky only the second state in the nation to use “change reporting” for SNAP instead of simplified reporting. This new practice would require any change in a SNAP participant’s life to be quickly reported to CHFS, including changes in income, work hours, savings, residency, a new household member or the loss of a family member, getting behind on child support or even a new car. The current practice simply allows SNAP participants to report any large changes that could affect their eligibility as they happen, while reporting any smaller ones during their recertification process which happens twice a year. But under HB 7, Kentuckians who make a mistake or are too slow to report life changes to CHFS could be required to repay the benefits they have received or accused of fraud (HB 7 also bans those accused of fraud from help with groceries, cash or medical expenses for either 6 months or permanently).

In practice, change reporting would require employees that are paid hourly, in tips or that have variable incomes each month of more than $100 to report those changes and provide documentation such as paystubs. For instance, restaurant workers, home health aides, retail cashiers and others would have to submit additional paperwork each month to continue receiving help with groceries. The additional administrative work created by “change reporting” for DCBS would also be extreme compared to current practice, slowing down the agency and making it harder for people to get and keep the assistance they are eligible for.

HB 7 would force working families that need help with food into scarce employment and training programs.

Many working adults without dependents or disabilities participate in SNAP; the abundance of poverty-wage jobs in Kentucky means they do not make enough to put food on the table. In addition to requiring them to report that work, HB 7 would require these Kentuckians to participate in a SNAP Employment and Training program, known as SNAP E&T. Despite efforts in the past decade, E&T infrastructure is wholly inadequate to support the program’s purported goals of conferring skills, training and experience to participants. For example, to participate, many Kentuckians would have to travel a good distance to access opportunities that are few and far between across the state, even as the program lacks any kind of transportation support.

HB 7 expands an existing ban from SNAP that takes food away from parents and their children.

Parents with low incomes who would struggle to keep food on the table without SNAP may also struggle to stay current on child support payments. When states punish parents for getting behind on payments by banning their participation in SNAP, both parents’ and children’s food security is diminished, with short- and long-term economic and health consequences. This harm, along with SNAP bans’ failure to increase child support payments and increased administrative costs, is why only 2 other states had these kinds of child support ban from SNAP as of 2018. Currently, Kentucky parents who do not have custody of their children can be banned from SNAP for getting behind on child support. An estimated 14,306 Kentuckians lost food assistance while the ban was in place from January 2019 and March 2020, and it was reestablished again last year with the passage of Senate Bill 65. HB 7 would expand the current ban to parents with children at home.

The ban is also rooted in wrong-headed stereotypes on single parenthood, and enforcing child support cooperation disrupts informal agreements, forcing families into formal arrangements in exchange for food.

HB 7 creates an illegal lifetime ban from public assistance.

HB 7 creates a two-strike ban that would keep people from participating in any public assistance program — Medicaid, SNAP, TANF and any other assistance program in Kentucky — for life for making a mistake or selling benefits from their EBT card. Federal research shows that the real fraud rate for SNAP is less than 2%. Despite that low rate, many more people are suspected of trafficking their card based on mistakes that are easy to make while using a card, such as entering in the wrong pin number too many times, shopping at the same store more than once in a day or having an purchase ending in a whole-dollar amount. This could result, for instance, in a new mom making a mistake while using her SNAP card being banned for life from things like child care assistance all the way to help with medical bills through Medicaid when she is a senior.

HB 7 takes away the ability of applicants of public assistance to attest to certain details about their life.

All applicants of public assistance programs, including Medicaid, must have various details about their income, work and household verified through documentation or database checks. But they can often get the process started through simply attesting to details like how many children they have, what their address is, or what their income is.

HB 7 would ban this practice in all forms for Medicaid eligibility. It would require, instead, that documentation be presented initially to prove these things before the process could continue, significantly slowing down the application and redetermination procedures and creating more opportunities for losing health coverage simply due to a paperwork issue.

HB 7 would recklessly and rapidly throw people off Medicaid, leading to nearly 200,000 uninsured.

In March 2020, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act which provided an extra 6.2 percentage point increase in what the federal government contributes toward state Medicaid programs. In order to receive that funding, states must provide a “Maintenance of Effort” (MOE) which includes keeping people covered by Medicaid unless they move out of state, pass away or ask to be disenrolled. This additional federal funding and MOE are in place until the quarter after the national Public Health Emergency expires. To ensure an orderly and accurate wind-down of the MOE that keeps at least 175,000 Kentuckians (though possibly far more) insured, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services has given states guidance and a full 12 months to process enrollees’ documentation to prevent the backlog of recertifications from overwhelming states’ systems. This guidance is geared toward ensuring that eligible Kentuckians don’t lose their Medicaid and those who are no longer eligible are given time to find coverage elsewhere so that as few of them become uninsured as possible.

Yet HB 7 would require the state to determine eligibility for and act on the Medicaid coverage of at least the 175,000 Kentuckians, including many children and seniors, within 60 days, rather than over the full 12-months provided by CMS guidance. CHFS does not have the staff to be able to process this volume of recertifications within such a condensed time frame. As a result, tens of thousands of eligible Kentuckians are likely to lose health insurance, and therefore their ability to fill prescriptions, see a doctor, or have other forms of health care covered. An overloaded DCBS call center would result in processing delays, meaning eligible Kentuckians who have submitted all required documentation could lose benefits, and leading to a large number of Kentuckians appealing their disenrollment, further jamming up CHFS personnel and creating a deep casework hole preventing other business from moving ahead. This bottleneck will also make it harder for families to get child care assistance, food assistance, home and community based service waivers and other kinds of supports, and take away critical funding from hospitals and providers’ offices across the commonwealth and the communities that rely on them.

HB 7 shuts the doors on presumptive eligibility Medicaid, a vital coverage option for Kentuckians and hospitals

HB 7 bans the state from providing temporary, “presumptive eligibility” Medicaid.

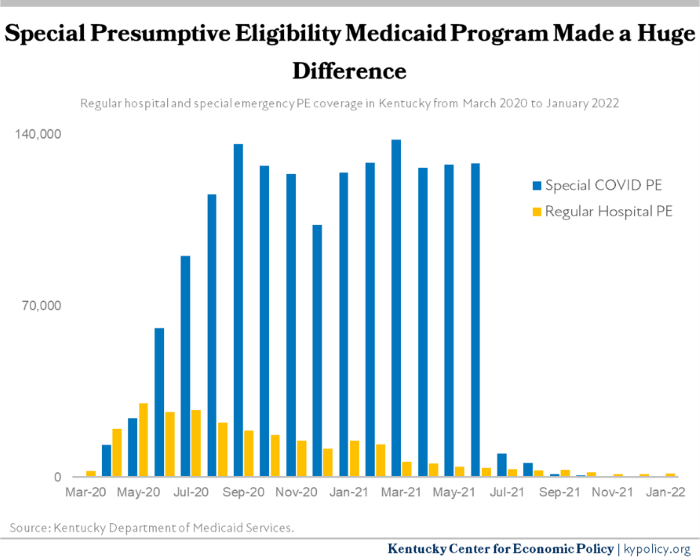

During the pandemic, Kentucky (along with many other states) was given permission by the federal government to offer health coverage for up to 6 months to Kentuckians who recently became uninsured. In doing so, CHFS extended a lifeline to hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians, while also keeping hospitals from closing their doors. But because this coverage is temporary, in July 2021 nearly 120,000 rolled off of it, and now very few people use it while they apply for full Medicaid or seek coverage elsewhere.

Banning the state from being able to provide presumptive eligibility Medicaid means that when the next downturn hits and tens or hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians lose their health coverage as they are laid off from work, Kentucky will have no tools to quickly offer health insurance. This will mean that Kentuckians will be forced to pay for the full cost of medicine out of pocket, will no longer be able to see their doctor, and uncompensated care will hobble hospitals — particularly rural hospitals.

HB 7 creates new requirements for hospitals and a potential ban on hospital-based presumptive eligibility.

Prior to the pandemic, hospitals were able to provide presumptive eligibility Medicaid to uninsured, indigent patients while they completed a full application. This form of coverage is most common among pregnant women, but could be extended to others as well. It usually represents a small number of Kentuckians at any given point in time, but is critical as it contributes to the fact that 48% of births in Kentucky are paid for by Medicaid.

Under the new restrictions, hospitals will be required to provide presumptive eligibility Medicaid patients with information about full Medicaid and help them fill out the application, then tell CHFS when they have done so on a regular basis. This in and of itself is a good requirement, as many low-income patients need help navigating what can be a lengthy and confusing application process. But after just three errors within a 12-month period, a hospital can be permanently banned from providing presumptive eligibility Medicaid to their patients — hurting both future patients and that hospital for as long as the hospital exists.

Costly new administrative red tape will slow all forms of assistance

HB 7 will necessitate a much larger state government administrative apparatus to implement. Requiring more paperwork to determine assets, implementing a change reporting requirement, no longer allowing self-attestation while applying for benefits and forcing hospitals to provide a stream of information about presumptive eligibility will require much more of CHFS. This large influx in casework will strain a workforce that is already 17% smaller than it was a decade ago. Low wages in state government have made it difficult to hire and retain workers who will be responsible for the increased caseload, which will likely lead to more resignations as has been the case for social workers and public defenders in recent years. A Family Support Specialist I, the entry-level position responsible for the casework increased under HB 7, earns only a little over $29,000, which is comparable to some fast food and warehousing positions in the state.

Additionally, with more casework and increasing resignations, Kentuckians applying for assistance not even covered by HB 7 will face longer call wait times and more disruptions in services. For example, if someone is having difficulty with their Child Care Assistance Program case, they will need to call the same Family Support Specialist who is also handling SNAP and Medicaid eligibility and application issues. As those staff get more and more behind on casework due to increased paperwork, other programs will have to enter a growing queue.

We can do better — HB 7 proves it

A strong safety net that works for everyone uses a “welcome mat” approach — offering applicants high-quality support, clear rules, an automated process and the benefit of the doubt. HB 7 actually proves that this can be done as it improves some parts of the application and renewal process by allowing online recertification, a pilot program for easing the application process for older Kentuckians known as the Elderly Simplified Application Project as well as making it easier for some Kentuckians over 60 or who are disabled to qualify for food assistance through a “Standard Medical Deduction.” It would also create a Transitional Benefit Alternative program that gives food assistance to families no longer receiving basic cash assistance through the state’s TANF program for up to 5 months after their TANF assistance ends.

Simplifying application processes, reducing barriers to keeping and using benefits, and offering applicants more leeway in navigating complex public assistance programs is good for families, our economy and state government. HB 7 should aim in that direction, and abandon the costly and numerous barriers it proposes.

Update Mar. 8, 2022