Working Kentuckians have faced widespread, unprecedented layoffs during the pandemic that worsened existing hardship and inequities. Despite extreme difficulty in navigating the outdated unemployment insurance (UI) system, unemployment benefits have been a lifeline for laid-off workers and kept our economy from falling into a deep depression. Yet, House Bill (HB) 4 would make unemployment benefits much harder to get and keep in the future, and push laid-off Kentuckians into poverty and lower-paying jobs. The bill does this through cutting the maximum available weeks a worker could claim benefits by up to 54%, further complicating the system through burdensome reporting requirements and new complex rules, and requiring that recently laid-off Kentuckians take any job available — even if it pays roughly half of what their previous job does.

Provisions like these have been implemented in other states to disastrous effect, exacerbating job loss and hampering local economies. HB 4 will especially harm rural Kentuckians who live in places where job opportunities are scarce, working-class Kentuckians who lose good-paying factory and coal jobs, and workers facing more discriminatory barriers to employment including Black workers and Kentuckians with disabilities. And past research has shown that provisions like those in HB 4 have led to poorer skills-matching between workers and employers, leading to lower wages, poorer employment outcomes and lower economic productivity. Further, the permanent cuts laid out in HB 4 would jeopardize Kentucky’s eligibility for federal UI funding that helps boost our economy during downturns, as well as the use of American Rescue Plan (ARPA) dollars for the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund.

Instead of stripping UI of its ability to get families and our economy through hard times, the General Assembly should learn the lessons of the past two years and create a system that works for, not against, workers — as the work-share provision of HB 4 does, alone. HB 4 as introduced will only deepen the economic pain so many working Kentuckians and local communities face during downturns.

HB 4 slashes unemployment benefits through cutting the number of weeks of benefits available

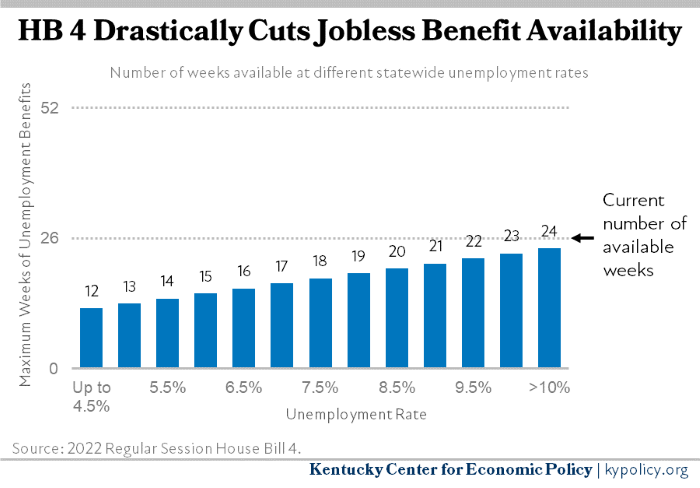

Currently in Kentucky and 41 other states, UI claimants can collect benefits for up to 26 weeks while seeking another job. HB 4 implements a system in which the total number of weeks would be cut by anywhere between 2 and 14 weeks. That number would vary based on the average unemployment rate of the first three months of the previous half calendar year — a practice known as “indexing.” In doing so, Kentucky would join just 9 other states that don’t offer the standard 26 weeks. If this plan were currently in place, claimants would have only 14 weeks of available benefits — a cut of 46% compared to the current number of benefit weeks. That’s because the average unemployment rate for July through September 2021 was 5.1%, which would be used under HB 4 to determine how many weeks laid-off Kentuckians could claim unemployment benefits until July 1, 2022.

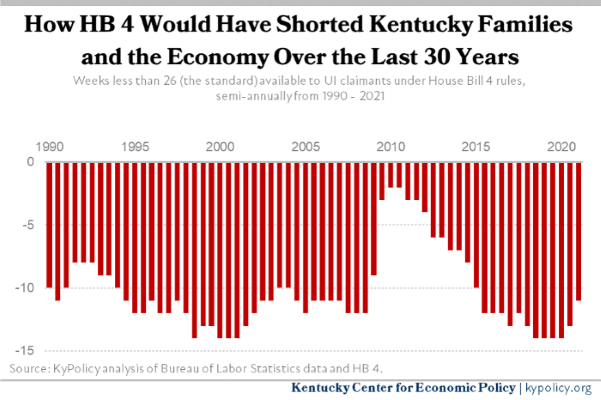

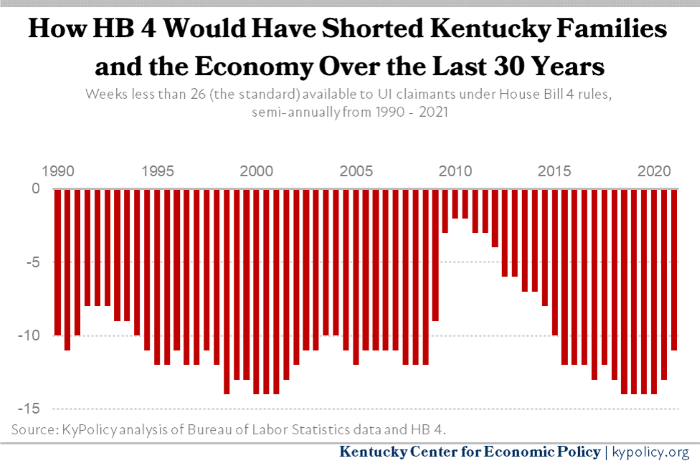

This scheme would have been especially catastrophic for many Kentuckians at the depths of the COVID-19 downturn, when unemployment soared as high as 16.9% in April 2020. The average unemployment rate from July through September 2019 was 4.1%, so that if HB 4 was in place at that time, Kentucky workers would have had just 12 weeks of available benefits when COVID hit. The economically depressed second half of 2020 would have been no better for Kentuckians in crisis, with just 12 weeks of benefits available due to the average 4.2% unemployment rate from January through March 2020. Going back to 1990, there have been 18 different 6-month periods in which the average claimant would have run out of benefits — pushing their families over the brink and undermining the resilience of Kentucky’s economy. During that same timeframe, Kentucky claimants would have lost out on 10.3 weeks on average.

At the county level, HB 4’s provision cutting weeks would create significant harm to workers in rural parts of the state that tend to experience much higher rates of unemployment than the state average. For example, while the statewide unemployment rate averaged 6% from 2011 – 2021, county level unemployment rates averaged up to 15.2% in Magoffin County, and 31 counties had an average unemployment rate at least 30% higher than the state average. In counties undergoing massively disruptive economic shifts away from mining and manufacturing, this provision would be especially harmful, cutting off a lifeline to workers facing little to no job options comparable to their prior employment, throwing families into turmoil and worsening the economic slump for entire rural communities.

Other Kentuckians would also face a disparate cut to benefits based on a statewide unemployment rate. For example, Black Kentuckians made up 16.4% of the unemployment insurance claims in December 2021, even though they made up only 9.3% of the workforce, and typically face higher rates of unemployment than white Kentuckians due to longstanding hiring discrimination, inequity in educational attainment outcomes and redlining that cuts off historically black neighborhoods from economic opportunity. Cutting off benefits early would take assistance away from a disproportionate number of Black Kentuckians. It would also disproportionately take away benefits from Kentuckians with felony records since employers tend to favor candidates without a felony conviction in their past. Kentuckians with a felony conviction in their past are 50% less likely to get a call back during an interview and face an estimated unemployment rate exceeding 27%.

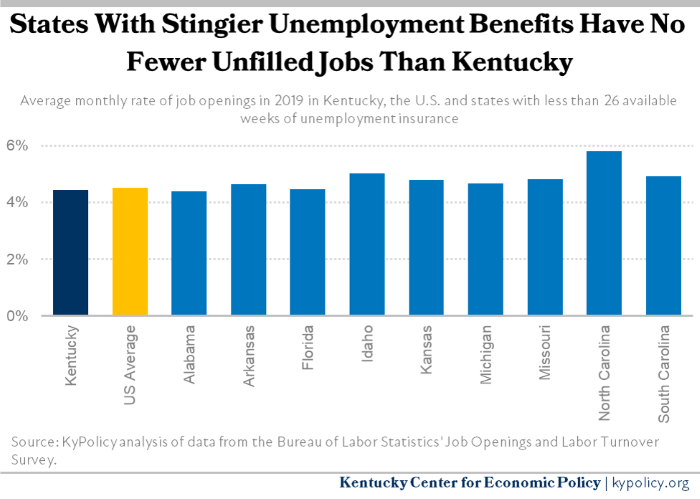

An argument at the core of this proposal is that restricting the length of time unemployment benefits are available to claimants will increase our labor force participation rate. In reality, the opposite is the case: Among the 10 states with the highest labor force participation rate, only one has a maximum duration below 26 weeks, whereas 5 of the 10 states with the lowest labor force participation rate have maximum durations below 26 weeks. When half of the states ended the federal jobless programs early last year, including the extra weeks of benefits allowed under Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation, it provided even more evidence that benefit duration does not have a meaningful effect on labor force participation. There was no meaningful difference between the states that ended benefits early and those that didn’t. And when all of the federal jobless programs later expired in September, the remaining states, including Kentucky, also did not see a commensurate uptick in employment. In fact, the largest month-over-month gain in employment over the past year in Kentucky came between July and August, while the benefits were still available. In addition, states that provide less than 26 weeks face the same degree of difficulty hiring workers at low wages as the rest of the country. Of the 9 states that offer less than the standard 26 weeks of benefits, only 2 had job openings at or below the national monthly average in 2019, prior to the implementation of extended federal benefits in 2020.

Moreover, during downturns when layoffs are high, job loss translates to less spending, which further precipitates layoffs in a vicious cycle. Unemployment benefits are a stopgap for the broader economy in that they replace some of the lost wages and prevent the economy from falling even further. An indexing scheme is slow to respond to a downturn, which can shed hundreds of thousands of jobs in a matter of weeks in Kentucky, as we saw in 2020. Already low recipiency rates (just under 1 in 5 unemployed workers in Kentucky) become even lower when states cut the maximum duration of benefits, which then dries up spending, speeding up the vicious cycle.

Another serious issue with shortening the maximum duration of benefits is that during especially severe downturns, the federal government will add “Extended Benefits” to the number of weeks a state offers of the lesser of either 13 weeks or half of a state’s maximum duration of benefits. By reducing the number of weeks of state benefits available, Kentucky will be turning down federal money to help laid-off workers when jobs are particularly scarce. Were the state to cap allowable duration to 14 weeks, for example, unemployed Kentucky workers would then only receive an additional 7 weeks of benefits, leaving an additional 6 weeks of benefits on the table at a time they are greatly needed.

Extremely strict rules for job searching and acceptance would push people into lower-paying jobs

Under current law, claimants must complete one work search activity per week, and must accept suitable work, which is broadly defined and gives the claimant the flexibility to accept a job that is nearby, aligned with prior training and offers comparable earnings to their previous position in a similar occupation. HB 4 puts significantly more pressure on claimants to quickly take any position, with little regard to needs and background. It does this by increasing work search activities from 1 to 5 per week, and after 6 weeks a claimant must take the first job that is offered if it:

- Pays 20% more than their current modest benefit amount

- Is located within 30 miles of where they live, and

- The worker is able and qualified to perform the duties regardless of whether or not they have related experience or training.

In order to enforce this, HB 4 requires the cabinet to perform weekly audits of claimant files to ensure work search requirements are being fulfilled and report on their findings to the General Assembly annually. HB 4 also establishes a system whereby businesses can report to the Office of Unemployment Insurance if a claimant scheduled for an interview or was offered a job and then turned it down.

Combined, these provisions create a scenario in which workers are quickly pushed into a job they are ill-suited for, outside of their career field and for lower wages. Unemployment benefits replaced roughly 45% of lost wages in 2021; thus, requiring claimants to take a job at 20% above their benefit amount would mean forcing them into a job that pays as little as 54% of their previous job. As of December 2021, the two occupations with the largest number of claimants were in the manufacturing and construction industries, accounting for nearly half of all claims. Under HB 4, these and other highly skilled workers would be required to take jobs that paid far less, very quickly, or else lose income support through UI. For example, a factory worker making $25 an hour who loses their job after a plant closes would have to take a job after 6 weeks even if it paid just $13.50 an hour. Like limiting the number of available weeks, the stricter work search and suitability provisions would harm workers and their families, as well as the economy when spending falls and employers struggle to find skilled workers because jobless Kentuckians have been forced to take earlier, lower-quality offers.

This requirement also increases the complexity claimants face in remaining eligible for unemployment benefits. More reporting requirements means more opportunity for paperwork glitches and missed deadlines, which will lead to procedural denials of benefits.

Research has shown that making unemployment less generous results in poorer skills-matching between employees and employers, and lowers the wages of claimants. And because future wages are often partially determined by wage history, policies like those in HB 4 that push people into lower wage jobs are trajectory-setting events, potentially lowering lifetime earnings.

Our state administrative systems are unable to handle these changes

Hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians applied for benefits in 2020, a large portion of them for the first time. What they encountered was a decrepit computer system built in the 1970s that was unable to quickly adapt to new programs, swells in caseloads and problems with claims. In response, claimants turned to staff in the Office of Unemployment Insurance for help, only to have calls and emails unanswered due to a long-term decline in staffing. The state is in the process of replacing this system, and proposals have been made to permanently increase staffing, but it is clear that years of neglect have left our unemployment system in dire disrepair.

It is this very same system that House Bill 4 would burden with a large increase in necessary back and forth with claimants. Submitting weekly proof of various kinds of work search activities, enabling weekly audits of sufficient size for statistical reliability, monitoring business complaints about claimants, and making semi-annual changes to the number of available weeks all require significant technological and administrative capacity that our system does not have. Nor does the current request for proposals and contracting process to replace our 50-year-old system include these details. If HB 4 were to pass, it would likely result in bidders pulling out of the process, further delaying what will already be a multi-year process of completing a new system. Further, it will require additional staff to carry out these tasks and handle issues with claims as they increase under HB 4’s stricter rules, for which the General Assembly has not recommended an appropriation.

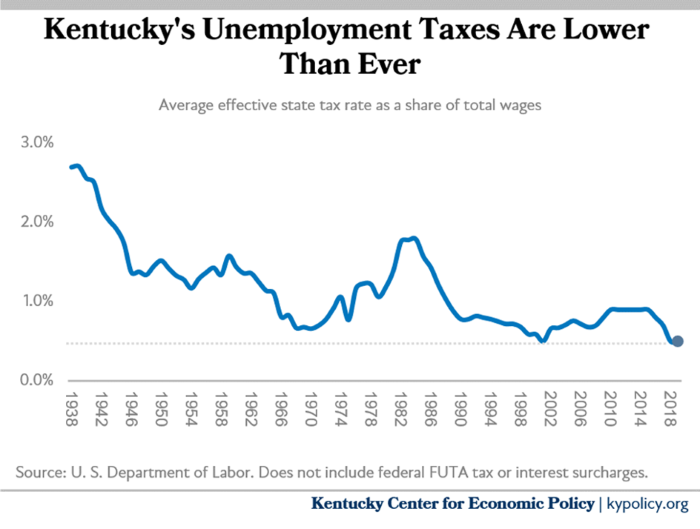

Cutting UI benefits for workers is a back door to cutting already historically low employer taxes

Kentucky employers are paying less as a share of total wages on contributions to the UI trust fund now than they have at any point in the program’s 84 year history. After HB 413 and a $506 million UI trust fund loan repayment from ARPA funds in last year’s session, followed by HB 144 and a proposed, additional $312 million deposit in the UI trust fund this session, employers’ UI trust fund contributions will remain extremely low. As of 2020, the average effective employer UI tax rate was only 0.4% of total wages.

Employer contribution rates are tied to a schedule that raises employer taxes when the UI trust fund is depleted and lowers them when it is full. By cutting off the number of weeks a claimant can receive unemployment benefits, and increasing denials through extremely strict work search and suitability standards, the General Assembly is indirectly lowering the employer contribution rate by reducing what is spent out of the UI trust fund. Essentially HB 4 provides a corporate tax break on the backs of laid off Kentuckians, in addition to subsidizing low-wage employers through pushing workers into low-paying jobs.

U.S. Treasury guidance on how states can use ARPA State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds allows for the kinds of deposits Kentucky wants to make into our UI trust fund. However, states cannot make these deposits while also reducing the amount of benefits paid or reducing the number of weeks UI benefits are available. That means if the General Assembly moves ahead with its $312 million deposit and passes HB4, the federal government could send Kentucky a bill for the $312 million later on.

HB 4 includes a work sharing proposal which is badly needed in Kentucky

Currently, 27 other states provide a short time compensation (STC, or often called work sharing) program to employers. It is a useful alternative to laying off workers that allows a managed reduction in hours for some or all of the employees at a business for a predetermined amount of time, with unemployment insurance paying some of the wages lost through the hourly reduction. It is good for employers because it means they get to keep an experienced workforce and won’t have to rehire later on for those positions. And it is good for employees who get to keep their jobs, lose less income, and keep their benefits such as health insurance and retirement. The General Assembly is right to propose this program, but not at the expense of the drastic cuts in the rest of HB 4.

UI isn’t the problem, low wages and the ongoing pandemic are

The past two years have shown in multiple ways how unemployment insurance reduces hardship but doesn’t reduce labor force participation. States with stingier access to unemployment benefits don’t have higher rates of unfilled jobs — as mentioned above, the opposite tends to be true. Rather, some business interests are using pandemic shifts in our economy to advance false narratives that would undercut workers’ leverage by taking away effective means of assistance. The facts tell a much different story: The historically high rate of quits among workers across the U.S. has not led to a decrease in employment. Rather employment is growing rapidly, especially when compared to past recoveries. People in general are not leaving work, they are leaving behind lower-paying jobs with little workplace flexibility for better ones. To the extent that some have left the labor force, much of that is due to increased retirements among workers over 65 who fear COVID-19 and workers age 25-54 who are out of the labor force due to caring for children and aging parents in an environment where child and elder care is very hard to find and afford.

If the General Assembly wants to improve Kentucky’s labor force participation, they should pursue policies that support workers through a higher minimum wage, more available and affordable child care and an increase in home and community-based services for the aging parents of working-age children. Cutting unemployment insurance benefits will harm Kentucky workers when they are already struggling, lower wages and spending, mismatch employees and employers, and make future downturns longer, harder and more painful for us all.