Roughly half of Medicaid enrollees in Kentucky had never heard of changes to Medicaid that could have led to the loss of their health coverage, according to new findings from researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health. Kentuckians’ lack of awareness about the waiver raises significant concerns about the state’s ability to effectively communicate important changes to people’s health coverage – changes that could mean the difference between keeping or losing it.

Many Kentuckians were not aware of changes that could cost them their health coverage

For the study, researchers interviewed 500 Kentucky adults with incomes that made them eligible for Medicaid between November 8 and December 30, 2018 – a critical period for testing familiarity with the changes as Kentucky’s Medicaid waiver was re-approved during this time (though the plan was again halted in court in March).

Perhaps the most striking finding of the study was that 54% of Medicaid-eligible adults had heard “nothing at all” about the policy to take coverage from those who don’t meet a work requirement. When looking at those actually enrolled in Medicaid, 46% had never heard of the change. For Medicaid enrollees who self-identified as black, Hispanic or other people of color, the findings are far worse: 61% had never heard of the policy.

The study also found that four in five Medicaid-eligible Kentucky adults were unsure if the policy to take coverage from those who didn’t meet a work requirement was yet in effect. Of the remainder – 12% incorrectly thought it was in effect and only 8% knew it was not.

Nearly everyone was meeting the work requirement, but could have lost coverage anyway

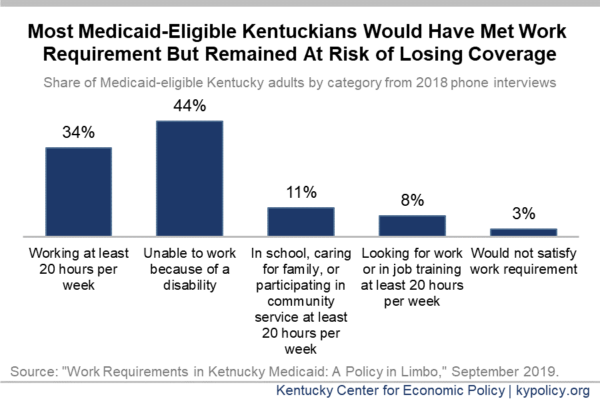

The study also found that all but 3% of Medicaid-eligible Kentucky adults would have technically met the work requirement because they were sufficiently working, in school, caring for a loved one, participating in community service or job training, or because they were disabled and unable to work. This finding is in line with other research about Kentucky’s Medicaid-eligible adult population.

This high rate of compliance is concerning because Arkansas’ rate of compliance was similar to Kentucky’s (95% and 97% respectively), yet there were 18,000 Arkansans who lost coverage during the months their waiver as in effect. It is likely that many who were technically in compliance with the requirement still lost coverage because they reported incorrectly or inconsistently, or because many who should have been exempt were not. Arkansas’ waiver applied to a smaller subset of its Medicaid enrollees, and was more lenient than Kentucky’s.

Kentucky state officials have argued that Kentucky’s experience won’t reflect that of Arkansas’, in part based on the claim that Kentucky’s public education about the requirement has been more robust. But the Harvard study shows those efforts may have been even less effective than Arkansas’. While 67% of Arkansans covered by Medicaid had heard of the changes (they were asked while the changes were in effect), only 54% of Kentucky Medicaid enrollees had. Additionally, among Arkansans who had heard of the policy, far less were confused about whether the policy applied to them. The authors conclude by saying:

“Arkansas implemented work requirements in 2018, and our survey showed similar patterns as in Kentucky — significant confusion, lack of awareness about the policy, and most adults already satisfying the proposed requirements. Further, the first six months of the policy were associated with a significant loss in coverage, eroding some of the improvements documented under the state’s Medicaid expansion, but no employment gains. These results highlight the potential effects of a Medicaid work requirement.”

With hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians’ health coverage on the line, this study adds to the already significant body of research warning against creating barriers to coverage – including work requirements. It also shows that the experience in Arkansas serves as a concerning bellwether for what Kentucky will experience should the courts allow it.