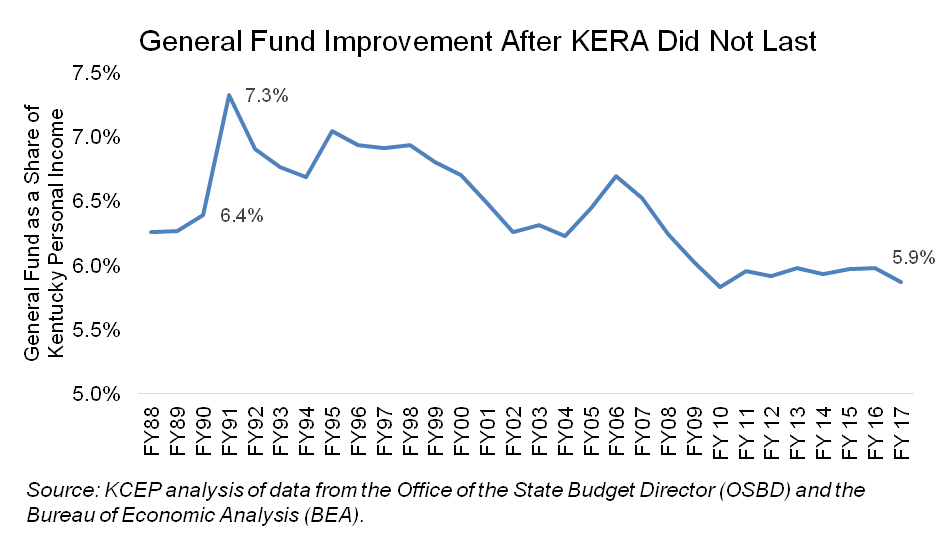

As a share of the economy, Kentucky’s General Fund is worse off today than before the last positive effort to clean up the tax code under the Kentucky Education Reform Act (KERA) took effect – 5.9 percent in 2017 compared to 6.4 percent in 1990 (see graph below). Due to the growing number and size of tax breaks in Kentucky’s tax code, General Fund revenue eroded relative to the economy for two decades after KERA and has largely stagnated since 2010. In fact, weak revenue growth in 2017 put the General Fund back on a downward trend.

The increase in revenue in the early 1990s was a necessary response to the 1990 Supreme Court ruling that the state was failing in its duty to provide an efficient system of common schools. Through KERA the General Assembly raised significant new General Fund revenue largely from cleaning up income tax deductions that higher income people were able to claim. Unfortunately, the revenue boost – which enabled vast equity and achievement gains in education – did not last for long, harming all areas of the state budget.

Though the difference between the General Fund as a share of the economy in 1991 and 2017 is just 1.4 percentage points, that represents huge revenue losses. If the General Fund in 2017 was 7.3 percent of the economy instead of 5.9 percent, we would have had $2.6 billion more to help make up for years of underfunding the pension systems, address our addiction and child protection crises, restore funding for K-12 schools and make college and housing more affordable, for example.

State Budget Director Chilton identified erosion in the two main sources of General Fund revenue – the individual income tax (42 percent of the General Fund in 2017) and the sales and use tax (33 percent) – as contributors to the problem. In the 2017 annual edition of Kentucky’s Quarterly Economic and Revenue Report, he wrote that “when one (or both) of these revenue sources fails to keep pace with economic growth, the remaining taxes have been struggling to pick up the slack.” Corporate taxes face problems due to too many loopholes, while coal severance and cigarette taxes apply to tax bases that are declining.

Because the real problem with our revenue system is its failure to track economic growth, the real solution is cleaning up tax breaks that cause the disconnect. Asking more from those at the very top of the income scale who are taking home the lion’s share of economic growth, and tightening loopholes that allow large corporations to avoid taxation are key examples of revenue generating reforms that will allow us to sustainably invest in the building blocks of thriving communities.

On the other hand, cutting income taxes (which primarily benefits the wealthy) and shifting to greater reliance on sales taxes (which primarily asks more of low and middle income Kentuckians) would further disconnect our revenue system from where the economy is growing. And moving away from income taxes will fail to propel economic growth as its proponents falsely claim.