Executive Summary

In 2014, the Kentucky General Assembly passed Senate Bill (SB) 200 with the goal of reforming the state’s juvenile justice system. The bill accomplished many of its primary goals, including the successful diversion of more children from the court system. But a decade after its passage, that progress is at risk.

False and harmful narratives suggesting a juvenile crime wave have taken hold among some in Kentucky’s General Assembly and new legislation rolling back aspects of SB 200’s reforms have passed in recent years. Kentucky risks the serious harms of again sending more kids to the state’s crisis-ridden secure detention facilities.

It is imperative, however, that Kentucky’s leaders remain committed to the ideals and evidence-based research that motivated SB 200. This paper includes recommendations to solidify the reforms of SB 200, build on its successes and avoid more of the proven dangers of harsher forms of punishment. They include continuing recent funding increases for alternatives to detention, additional funding for agencies and services required to improve outcomes for children, new data tracking and reporting rules, rolling back recent laws related to the detention of children and truancy, and focusing on addressing the racial disproportionality that has worsened in the juvenile justice system.

Introduction

Last year marked the 10th anniversary of the passage of SB 200 (2014), comprehensive legislation that transformed Kentucky’s juvenile system and established the state as a national leader in juvenile justice reform. SB 200’s goal was to reduce the number of children interacting with the formal court system to achieve better outcomes for kids and families while reducing expenses for the state. The results have been dramatic — with significant increases in the number of children successfully diverted away from the courts and meaningful decreases in the number of kids in out-of-home placements or under supervision in the community.

There is much work ahead, however, for the state to more fully transform the juvenile system in ways that benefit Kentucky kids, communities and the state as a whole. Too many children are still processed through the formal court system. Racial and ethnic disproportionality within the juvenile system continues, and in some cases has worsened with the implementation of SB 200’s reforms. Promised investments in community-based programs remain unrealized, limiting the effectiveness and availability of diversion opportunities. And a renewed legislative focus on harshening penalties and punishment for children, based on false narratives of a juvenile crime wave, threatens Kentucky’s ability to build on or even sustain the successes of SB 200.

This report examines the state’s progress on juvenile justice reform over the past 10 years, identifying notable successes as well as shortfalls. The report concludes with policy recommendations that further build on the state’s accomplishments and lessons learned – ranging from providing more and better mental health services in schools, gathering more data, and providing funding needed to support community programs.

In conducting the research for this report, we interviewed more than 20 people who were or are currently involved in the administration of Kentucky’s juvenile justice system. We are grateful to these individuals, whose insights and suggestions informed the project in numerous ways and have been incorporated throughout.

Reviewing the history and significance of SB 200 at 10 years enables the examination of a wealth of research, data and other information that has been amassed since the legislation was enacted. It is also a time when only 13 current legislators – five representatives and eight senators – were members of the General Assembly when SB 200 passed and thus have institutional knowledge of the legislation’s goals and the research that supported its passage. A fuller understanding of SB 200 can help inform decisions about juvenile justice moving forward, including the significant issues the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) is facing with its detention centers.

The leadup to SB 200

Conversations in Kentucky about juvenile justice reform in the early 2010s were part of a growing national recognition that many prevailing practices, such as the use of secure detention and other out-of-home placements, were largely ineffective and even harmful and counterproductive, especially for children with low-level offenses. At that time, juvenile crime rates were falling both nationally and in Kentucky, which resulted in fewer youth in the court system. However, despite fewer Kentucky kids being “committed to” (under the legal authority of) DJJ or the Department of Community Based Services (DCBS), there was a significant uptick in the number of kids in out-of-home placements, primarily in residential group homes or secure detention facilities.

In response to this increase, the Kentucky General Assembly established the Task Force on the Unified Juvenile Code in 2012, with members from all three branches of government as well as other juvenile system stakeholders.1 With technical assistance and support from The Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew) and the Crime and Justice Institute (CJI), the task force met numerous times over a two year period to examine data and research related to the state’s juvenile system policies and practices, hear testimony from a range of stakeholders and experts, and develop recommendations for reform. The task force’s findings and recommendations were published in December of 2013 and became the basis for SB 200 in 2014.2

Among the task force’s key findings were:

- More than half (55%) of children in out-of-home placements with DJJ were there either for misdemeanor offenses or for violating a condition of their court-ordered community supervision.3 Of those in out-of-home placements for felony offenses, many were for Class D felonies, which are the lowest level.

- Many children in out-of-home placements were committed to DCBS for “status offenses,” which are behaviors such as truancy and running away that are not crimes if committed by an adult. DCBS was spending an estimated $6 million annually for those out-of-home placements.4

- The difference in time spent in out-of-home placements by children with felony offenses compared to those with less serious violations or misdemeanor offenses was less than a month.

- One reason for the increased number of children with less-serious offenses in out-of-home placements was a lack of available and/or accessible community-based services to which they could be referred.

- While community-based services were underfunded, the average cost of a bed at one of the state’s secure juvenile facilities was $87,000 a year.

- Critical decisions about sanctions and placements were being made in juvenile cases without consistent use of objective decision-making tools by the agencies involved.

- More than half of juvenile “complaints,” which are formal allegations that a child committed an offense, came from schools.

The task force also reviewed juvenile justice research studies, which found that the out-of-home placement of children does not reduce their likelihood of reoffending and instead may actually increase the likelihood they commit a new offense. Longer lengths of stay in secure facilities do not necessarily reduce “recidivism,” a term for when a person returns to the system within a couple of years. At the same time, using resources to focus on children with high risk factors for reoffending does reduce recidivism.5

The task force recommended focusing out-of-home placement on children with higher-level offenses and reinvesting a portion of the resulting savings in proven strategies that achieve better outcomes for kids. The report offered 18 specific recommendations for juvenile justice reform in four broad areas, including the following:

- Reinvest savings, and provide sustained funding to expand community services and improve supervision – The task force recommended establishing a fiscal incentive program to reinvest the savings from fewer out-of-home placements in evidence-based programs and services for children and their families to help keep children out of the juvenile justice system, and in community supervision and services to help children who have become involved in the juvenile justice system remain in their communities, or successfully reintegrate following an out-of-home placement.

- Focus resources, particularly expensive out-of-home facilities, on higher-level offenders – Recommendations included making consequences less restrictive for children who commit lower-level offenses and establishing a framework to guide the use of out-of-home placements for them. The task force also called for the use of graduated sanctions for all supervised youth, expansion of community-based early intervention and prevention services, as well as mediation and restorative justice services for children against whom complaints have been filed. In addition, the task force recommended increased training for judges, prosecutors, law enforcement and front-line staff about research relating to brain development, effective interventions, and the impact of out-of-home placements.

- Increase effectiveness of juvenile justice programs and services – The task force recommended working with parents to increase involvement in juvenile interventions, establishing more uniformity across the state to reduce court referrals from schools, including a review of the roles and responsibilities of School Resource Officers (SROs), helping schools reduce court referrals, and increasing requirements for DJJ supervision and aftercare.

- Improve government performance – Lastly, the task force suggested a new committee to provide ongoing oversight of the implementation of the new policies and to monitor performance measures, new data collection and reporting requirements related to recidivism, new data reporting requirements from schools and courts, and renewed efforts to maximize the use of available federal funds.

SB 200 made significant changes to Kentucky’s juvenile justice system

The task force’s recommendations were well received by Kentucky lawmakers and gained momentum quickly with the introduction and passage of SB 200 during the 2014 General Assembly.6 The bill was amended several times as it worked its way through the legislative process, in most cases to reverse proposed reforms that would divert more children away from the formal court process.7 Despite these amendments, however, SB 200 made significant changes to Kentucky’s juvenile justice system.

The goals of SB 200 included protecting public safety, holding youth accountable, and improving outcomes for youth by, among other things:

- Reducing commitments, out-of-home placements and the use of secure detention for system-involved children;

- Diverting more children, particularly those with status and low-level public offense (misdemeanor and felony) complaints, away from the court system, and providing those children and their families with evidence-based programs and services in the community; and

- Investing savings from the reduction in out-of-home placements in evidence-based community programs and services through a competitive grant program.

Key components of the legislation:

- Mandated diversion in some cases and expanded eligibility for diversion –The law required diversion for children with a misdemeanor complaint and no prior adjudications or diversions and prohibited the county attorney from filing a petition against those children. Prior to the passage of SB 200, there were no mandatory diversions for children accused of committing a public offense.

- Established Family Accountability, Intervention and Response (FAIR) teams to reduce youth court involvement –Multidisciplinary FAIR teams were required in all 60 judicial districts to reduce youth court involvement by providing enhanced case management for youth assessed as having high needs or who are struggling in diversion, and to facilitate communication among different agencies involved with youth.8

- Put limits on commitments to DJJ –The law prohibited the commitment of some youth with lower-level offenses to DJJ.9

- Established time limits for out-of-home placements and supervision –Limitations were established for the amount of time children can remain in out-of-home placements or under supervision by DJJ based on the seriousness of the offense and likelihood of the youth reoffending.

- Created a system of graduated sanctions –The law established a sequence of appropriate graduated responses by the court for youth on diversion and probation who violate conditions.10

- Mandated the use of needs and risk assessment tools and evidence-based screenings and assessments – These tools help to better identify the needs and risks for children and their families so that appropriate services and programs can be provided.11

- Established an oversight body – The Juvenile Justice Oversight Council (JJOC) was established to review performance data, track the implementation of SB 200, offer continuing oversight and make recommendations for system changes.12

- Required enhanced data collection and reporting – New data collection and reporting requirements were established, including a centralized data system to be maintained by the Justice Cabinet to analyze juvenile recidivism. In addition, AOC was required to collect and track data to provide an annual report to the JJOC including the number of complaints filed, the outcome of each complaint, and specific information about children accused of status offenses.13

- Enhanced training requirements – Judges, prosecutors, and staff working with children and youth became subject to more robust training and education requirements.

- Established new funding for community programs through a competitive grant program –A competitive program was established to use anticipated savings from the reduction in the number of youth in out-of-home placement to support renewable grants to be awarded to judicial districts to provide more community-based programs and services. These grants would support alternatives to out-of-home placements and provide individualized interventions to avoid commitments to DJJ. Continued funding under the program required reductions in detention admissions, commitment of children on public offenses, and the use of prosecutorial overrides compared year over year.14

To achieve its objectives, SB 200 also amended the statute that establishes the express legislative purposes of Kentucky’s juvenile code to direct that:

Emphasis shall be placed on involving families in interventions developed for youth, providing families with access to services necessary to address issues within the family, and increasing accountability of the youth and families within the juvenile justice system;

To the extent possible, out-of-home placement should only be utilized for youth who are high-risk or high-level offenders, and that low-risk, low-level offenders should be served through evidence-based programming in their community; and

As the population in Department of Juvenile Justice facilities is reduced through increased use of community-based treatment, and if staffing ratios can be maintained at the levels required by accreditation bodies, reductions of the number of facilities should be considered.15

SB 200 was implemented over several years and involved many systems changes

The implementation of SB 200 took several years and was primarily the responsibility of AOC and DJJ, with involvement by the Department for Behavioral Health, Developmental and Intellectual Disabilities and DCBS. AOC is the operational arm of the Judicial Branch and is the home of the Court Designated Worker (CDW) program. CDWs process all complaints against children prior to any formal court action and played an integral role in the implementation of SB 200. The changes required by the legislation were significant and included the establishment of new positions at AOC, data system updates at AOC and DJJ, collaborative cross-agency agreements, the establishment of FAIR teams, and extensive, comprehensive training about the new requirements for DJJ staff, CDWs, DCBS staff, judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys.16

Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile system was not one of the goals identified by the task force or in SB 200. However, after SB 200 passed, Kentucky was accepted as one of the inaugural participants in a comprehensive juvenile justice system improvement initiative through the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). That initiative had as one of its central goals addressing racial and ethnic disparities, along with the adoption of developmentally appropriate evidence-based practices, maximization of cost savings for the state while holding youth accountable, and improvement of outcomes for youth. Through this initiative, OJJDP provided training and technical assistance that supported implementation of the sweeping changes included in SB 200, with a focus on eliminating racial and ethnic disparities within the system.17

In the first six years after the passage of SB 200, four independent studies examining different aspects of the implementation and impact of SB 200 were published — three by the federal Office of Justice Programs (OJP) (2019 and two in 2020) and one by the Urban Institute (2020).18 The studies looked at several different metrics and all found evidence of progress comparing data before and after the passage of SB 200, including an increase in the number of cases diverted for all youth, an increase in successful diversions even with more youth being diverted, a reduced risk of recidivism, and a reduction in the number of commitments to DJJ though without a corresponding reduction in out-of-home placements.19 The studies also recognized the importance of the intentional development of an implementation plan and the delivery of trainings by AOC to inform and educate judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, staff and others working with children across the state in achieving the successes.

Recommendations from these studies included examining unintended consequences of prosecutorial overrides, which occur when a child qualifies for diversion, but the prosecutor instead decides to process the case through court, expanding the types of low-level offenses that may be considered for mandatory diversion referral, evaluating the implementation of the fiscal incentive program, exploring why roughly 10% of youth taken into custody were detained, and examining why roughly 20% of youth who had first-time misdemeanors did not enter into a diversion agreement. They also recommended the continued collection and evaluation of data to track trends and long-term outcomes for youth, and periodic needs assessments to identify gaps in services. All the studies identified the continuation of racial and ethnic disproportionality as concerning and recommended additional work to address these issues.

Although the reports summarized above were not released until 2019 and 2020, the issues they identified were also being discussed by the JJOC, DJJ and AOC as the implementation of SB 200 was ongoing. Senator Whitney Westerfield, the sponsor of SB 200, introduced comprehensive legislation during the 2016, 2017 and 2019 legislative sessions that would have provided further support for reform efforts, including, among other provisions, enhanced data collection and reporting requirements, greater focus and planning by school districts and state agencies to address racial and ethnic disproportionality and disparities, more robust training for staff interacting with youth, and expansion of the situations in which mandatory diversion would apply. Although the bills all did receive at least one committee hearing, none passed out of the Senate.20

The goals of SB 200 are supported by research

SB 200 was based in part on the premise that the juvenile justice system should be fundamentally different from the adult correctional system based on scientific evidence that children are developmentally different from adults, and those differences are significant and relevant in terms of criminal responsibility and the possibility of rehabilitation. The design and purpose of the juvenile system should therefore be focused on keeping children in their communities whenever possible, with the support and services necessary to help them succeed.

Brain development influences actions

There has been a great deal of research both prior to and following the passage of SB 200 confirming the damaging impact of incarceration on children. One of the reasons harsh punishment is ineffective for children is that their still-developing brains cause them to be impulsive, more likely to not understand the consequences of their actions, and more likely to be motivated by peer pressure.21 Further, the parts of the brain governing sensation-seeking and risk taking are more active. This lack of brain development makes risky behaviors more likely during adolescence and makes it less likely that punishment will work as a deterrent for young people as their brains are not yet mature enough to link actions with potential consequences.22 Research shows that young people respond more positively to rewards than punishment, and that adolescence may be a peak time to learn and be rehabilitated.23 The circumstances described here are not an aberration – they are simply part of normal brain development. The United Supreme Court has recognized on numerous occasions that because of these differences children should be treated differently than adults.24

Research also shows that as the brain develops, most youth age out of lawbreaking and risky behavior.25 But incarceration during adolescence slows this process, impeding the ability to develop better impulse control, delay gratification, weigh the consequences of actions, and resist peer pressure – producing the opposite effect of what is needed for growth and progress.26

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) affect behaviors

ACEs are traumatic events experienced by children between the ages of 0-17. Examples of ACEs include: violence, abuse or neglect; witnessing violence in the home or community; having a family member attempt or die by suicide; members of the child’s family experiencing substance use or mental health problems; and instability due to parental separation or due to a household member being incarcerated. There are many systemic factors that play a role in childhood health and behavior, and research demonstrates that children who experience more ACEs are significantly more likely to end up in the juvenile justice system.27

A vast majority of the children who come into contact with the courts have experienced violence and trauma, and their reactions (including gang involvement, substance use and aggression) are often responses to that trauma and are not effectively addressed through harsh punishment. To better understand the impact of childhood trauma and violence on justice system involvement, OJJDP funded seven studies in 2016. The studies also looked at possible protective factors that could reduce the likelihood of children entering the juvenile system, and the effectiveness of possible interventions. An article synthesizing the findings of the studies identified the following:

- Justice-involved youth had high levels of trauma prior to system involvement and were subjected to ongoing trauma during and following justice system involvement.

- There is a relationship between continuous exposure to violence and adult reoffending.

- There is strong support demonstrating the relationship between trauma and justice system involvement.

- Potential protective factors identified were a strong connection to school, good relationships with a mother or father figure, and “high levels of neighborhood collective efficacy.”

- Trauma-informed practices as a whole produce positive results for at-risk youth who experience trauma.28

Research demonstrates harms of incarceration and harsh punishment on children

A recent publication summarizing the research identified that:

- Incarceration does not reduce delinquent behavior, and confinement most often results in higher rates of rearrest compared with other community-based alternatives.

- Incarceration pending a court hearing increases the likelihood that a child will move further into the system and be placed in residential custody if they are found delinquent.

- Secure detention increases the likelihood that a young person will be arrested and incarcerated as an adult.

- Longer stays in detention often increase rather than reduce recidivism rates.

- Incarceration negatively impacts success in education and employment, and the effects are long-term.

- Incarceration is itself a traumatic experience and can exacerbate difficulties a youth is already experiencing due to prior trauma, leading to poor behavior during incarceration.

- Incarceration exacerbates physical and mental health problems, results in poorer health as an adult and is associated with shorter life expectancy.29

Because of these realities, a juvenile system focused on community-based rehabilitation and support rather than incarceration will be more effective in serving children and families. Such a system will also be more cost-effective as youth who are provided support and encouragement in their communities as they grow and mature will be less likely to recidivate and have better health, educational outcomes and job opportunities.

SB 200 Successes and Challenges: What the Data Shows after 10 Years

The Successes

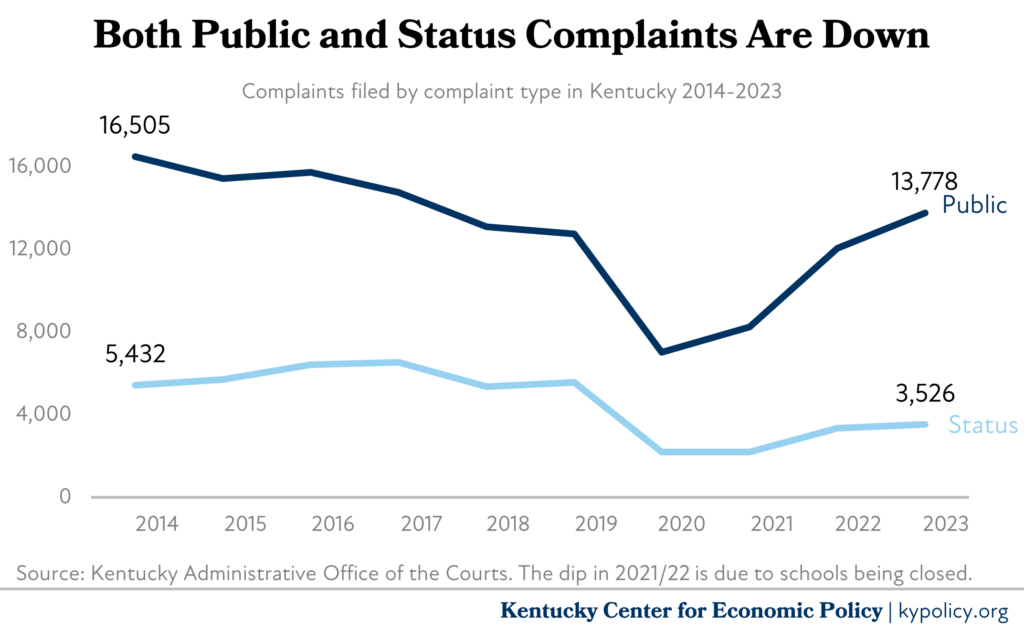

Ten years after the passage of SB 200, data shows meaningful progress in achieving two of its primary goals. The changes implemented through SB 200 have worked to significantly reduce the number of children who become deeply involved in the juvenile justice system, and to increase the number of children who are successfully diverted away from the court system. The data also shows that these goals were accomplished without an increase in juvenile crime. In fact, the number of juvenile complaints – the equivalent of charges for adults – has declined significantly in the past decade.

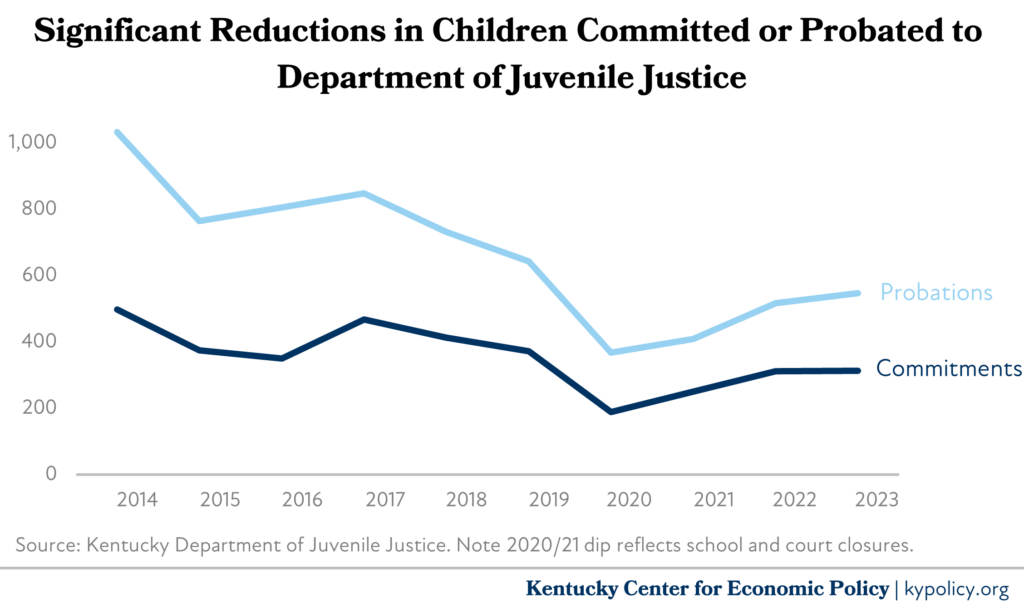

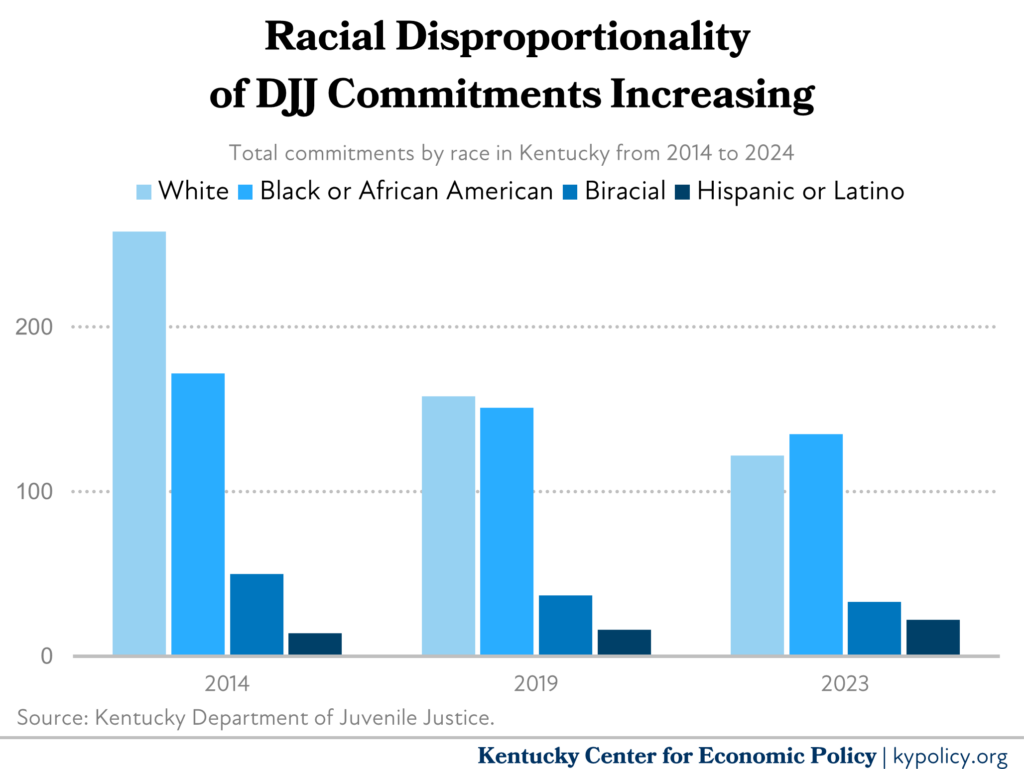

Fewer children are committed or probated to DJJ, resulting in the closure of residential facilities

As illustrated in the graph below, total commitments to DJJ have decreased from 497 in 2014 to 313 in 2023, a 37% decrease. The number of children probated to DJJ (probated means supervised by DJJ but not committed to DJJ) has decreased from 1,033 in 2014 to 547 in 2023, which is a 47% decrease. These reductions may, in part, be explained by a 17% reduction in the total number of public offense complaints filed comparing 2014 to 2023; however, even taking that into account, commitments and probations to DJJ are significantly down.30

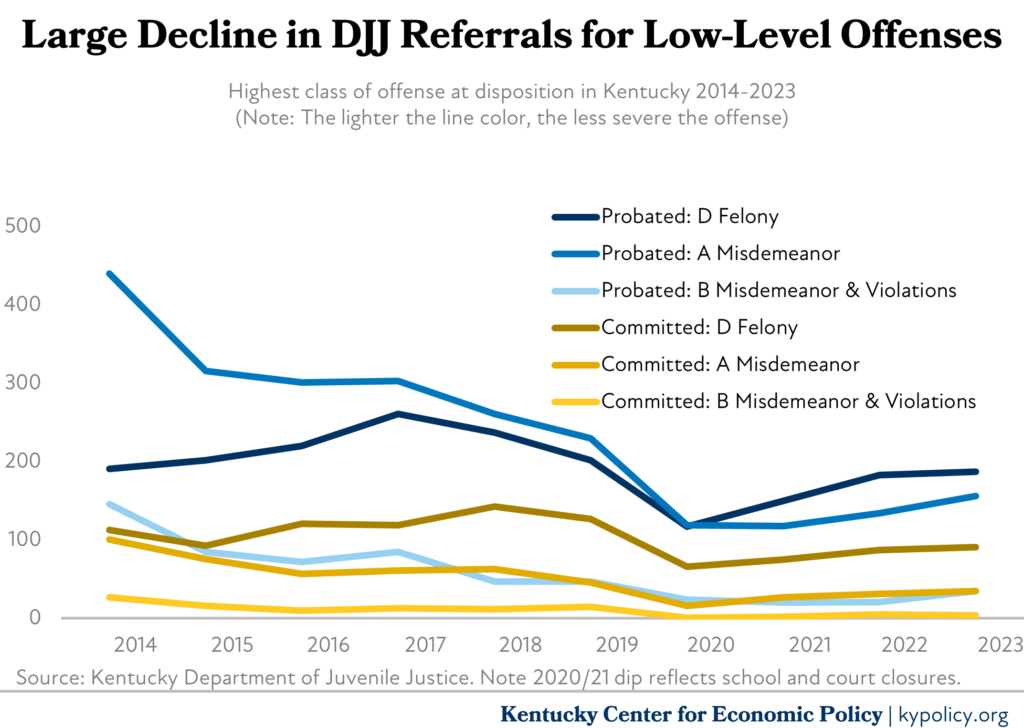

Looking only at children with low-level offenses, the reductions in both commitments and probations are significant for children with violations and misdemeanors but have not changed much at all for children with Class D felonies, as illustrated in the graph below. The number of children committed to DJJ for misdemeanors and violations has decreased from 128 (26% of all commitments) in 2014 to 39 (12% of all commitments) in 2023. The number of children probated to DJJ with a misdemeanor or violation decreased from 586 (57% of all probations) in 2014 to 191 (35% of all probations) in 2023, a 67% reduction.

This data illustrates that the provisions of SB 200 have been successful in reducing the overall commitment and probation of children to DJJ, and this is especially true for children who committed misdemeanor offenses and violations. However, the data underscores the need for additional research about children who are committed and probated to DJJ with Class D felonies, as that number has remained roughly the same throughout the past 10 years. In addition, there were still 39 children committed, and 191 children probated, to DJJ in 2023 with non-felony offenses, and it is important to understand why.

At the time of its passage, SB 200 was projected to reduce DJJ’s out-of-home population by more than one-third, saving Kentucky more than $24 million over five years by shifting lower-level youth away from out-of-home placements in favor of community-based programs.31 These reductions did in fact occur and as a result, DJJ closed three residential juvenile facilities with a total of 98 beds in 2016 and 2017, which reduced DJJ operating expenses by more than $4 million per year.32

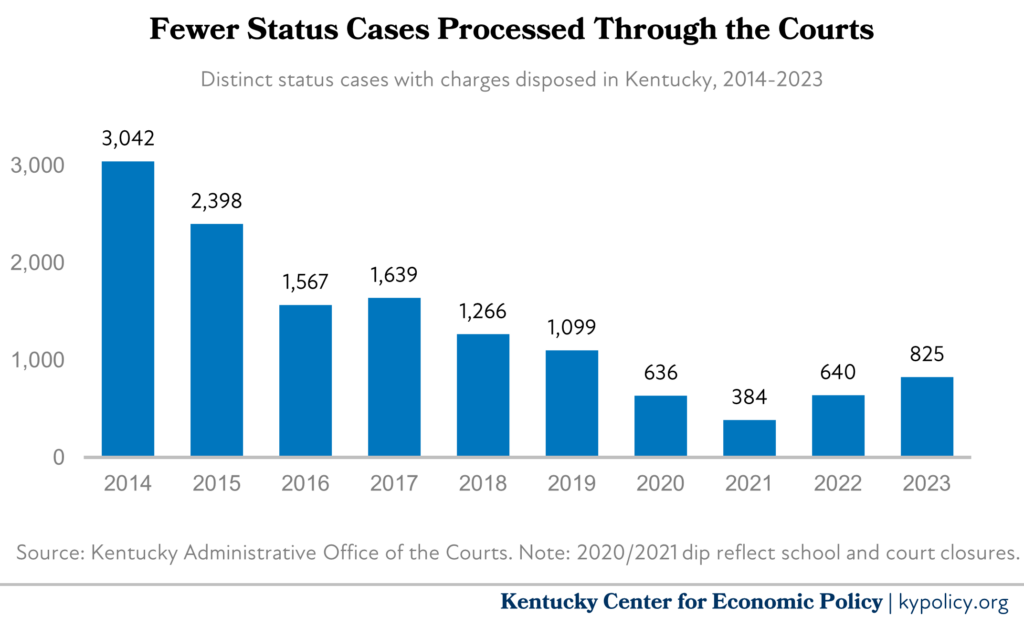

Fewer status cases are processed through the courts

Another goal of SB 200 was to reduce the number of status cases processed through the courts, and the data shows a 73% reduction in such cases between 2014 and 2023, as illustrated in the graph below. As was the case with public offense complaints, status complaints declined by 35% between 2014 and 2023, so that decline was responsible for a portion of the reductions; however, a majority of the reduction in cases processed through the courts were the result of kids being diverted. Truancy cases that ended up with a formal court referral decreased from 25% in 2014 to 18% in 2023.33

More children are successfully diverted from the formal court system

Because more children received diversions and more diversions were successful, the share of all closed complaints that were diverted increased from 42% to 56%. The share of diversion-eligible complaints that were closed by diversion was 71% in 2023, compared to just 62% in 2014. Diversion success rates increased from an average of 85% to over 93% from 2014 to 2023.34

FAIR Teams play an important role in successful diversions

Referrals to FAIR team for status offenses have been steady over the past 8 years, consistently between 11% to 13% of complaints filed, with most of the referrals occurring for children classified as high needs, or who were unsuccessful in diversion initially. Between 2016 and 2023, FAIR team referrals statewide have averaged 2,300 per year. Of the children sent to a FAIR team, a majority of these complaints have been closed through dismissal or successful diversion, even though those children generally have high needs or were unsuccessful at initial attempts at diversion.35

Juvenile crime is down

The data also shows that public safety has been maintained, another goal of SB 200, even as more children have been diverted from the court system and fewer have been committed or probated to DJJ. As can be seen in the graph below, juvenile complaints for public offenses have decreased by 17%, while complaints for status offenses have decreased by 35% comparing 2014 to 2023. This graph clearly demonstrates that the rhetoric about a juvenile crime wave that fueled the clawing back of some of the provisions of SB 200 over the past few legislative sessions was not supported by the data. In reviewing this graph, it should be noted that the large dip in complaints in 2021 and 2022 occurred because schools were closed for a portion of both years, and schools produce half of all juvenile complaints.

Many additional successes of SB 200

Not all of SB 200’s successes are reflected in the data. Among its many other successes are more training for judges, prosecutors, DJJ workers, CDWs and others involved in the system, and better communication and collaboration across agencies. Over several years AOC has developed and is implementing an evidence-based case planning approach focusing specifically on the individualized strengths and needs of each youth rather than using a compliance driven process.36 AOC invested significant time and resources to ensure that the provisions of SB 200 were implemented with fidelity and integrity across the state and continues to lead in these areas.

The challenges and recommendations to address them

The data clearly demonstrates that SB 200 has been successful both in reducing the number of children who are processed through the court system and the number of children who are committed or probated to DJJ. But there is still much work to be done for the full promise of SB 200 to be realized. Key challenges include lack of funding for community programs, recent legislation that threatens the progress already made, the unacceptably high number of kids being detained and the racial disproportionality of that population, the increase in school complaints and prosecutorial and judicial overrides, and detention at intake happening more frequently.

Lack of funding for community programs hampered the implementation of SB 200 and has continued to limit progress

SB 200 acknowledged the need for additional funding for community-based services and sought to address that need through the creation of a competitive fiscal incentives program that would invest 25% of the savings generated from a reduction in youth committed to DJJ in a competitive grant program to fund community-based services. Despite this program being one of the signature components of SB 200, there have been no funds provided other than a one-time appropriation of $900,000 in fiscal year 2017 that supported funding for an 18-month period from Jan. 1, 2018, through June 30, 2019, to 19 judicial districts.37 These funds were provided only once despite recurring savings of over $4 million dollars at DJJ generated through the shuttering of three DJJ residential facilities including 98 beds in 2016 and 2017.38 SB 200 also required the reinvestment of the other 75% of savings in DJJ day treatment centers, which are community-based centers that provide education, treatment, and other programming (25%) and DJJ community supervision and aftercare services (75%). However, not only were these savings not made available for reinvestment, but they were also taken out of DJJ ‘s budget entirely, with base reductions of $1.1 million in fiscal year 2016, $2.3 million in fiscal year 2017, and $3 million in fiscal year 2018.39

Further, despite the need for extensive systems changes and increased responsibilities for AOC, no new funding was provided to AOC as part of SB 200 or in any budget since. AOC was assigned the responsibility of establishing and supporting the FAIR teams, including the creation of new positions to help oversee and support them; the duties of the CDWs were significantly increased; and data and reporting requirements for AOC were expanded. More children were diverted from the court system, increasing the need for community-based services. Yet AOC was not provided funding for these programs or services either, despite being responsible for many of the children who need them.

To address the lack of funding for AOC, DJJ and AOC have worked together over the years to collaborate and ensure that the children in AOC diversion programs can access limited community services paid for by DJJ; however, those same programs must also serve youth committed to or supervised by DJJ or diverted from detention, in addition to youth supervised by the CDW program, and the availability of services to the CDW program has not been sufficient to address the needs.

We learned from our interviews that there have never been enough community services and programs available for all the children and families that could benefit from them, especially in rural communities. We also learned that many of the programs and services that were available prior to COVID have shuttered, changed their missions, or no longer accept system-involved youth, making an already challenging situation even more difficult. Lack of community services has hindered the ability of FAIR Teams and CDWs; along with DJJ Detention Alternative Coordinators (DACs), who help to coordinate alternative placements to detention for kids; to aid children and families to the extent that they could, resulting in inappropriate detention placements of children who did not have to move deeper into the system.

The 2024-2026 budget did, however, provide some increased funding to the DJJ Alternative to Detention program, which seeks to find alternative placements for children that would otherwise be in secure detention, with $3.9 million in each year to support 450 additional placements.40 The budget also provided DJJ with an additional $3.5 million each year to support evidence-based programming, including 21 new social services specialists, youth screening tools, and staff to coordinate services.41 These investments are promising and represent a good start to providing what is needed for community support to be as robust as the demonstrated need.

The 2024 General Assembly also enacted legislation requiring DJJ to establish a local restorative justice advisory committee in each county and appropriated funding to support these efforts. DJJ subsequently entered into a two-year contract with Volunteers of America, which is currently providing restorative justice services to youth in 20 counties, to expand their services to other counties and more youth. Restorative practices, which focus on repairing harm rather than punishment, have been shown to strengthen communities, enhance accountability, and reduce recidivism.42

Recommendations

The results that AOC and DJJ have achieved in significantly reducing the number of children who become more deeply involved in the juvenile justice system are remarkable, especially given the lack of investment in community services and programs, data systems and program evaluation over the past 10 years. To continue moving the system forward in ways that benefit children and families, it is crucial that these investments be made in the next budget, and that they be sustained over time. Specific recommendations include:

- Continue the 2024-2026 funding increases for DJJ for alternatives to detention and evidence-based programming and support additional needed capacity within DJJ

- Provide funding for more DACS – DJJ requested funding to hire additional DACs because they experienced a 125% increase in youth served annually from 2020 to 2022 and anticipate annual growth of 20% a year in the future.43 Additional positions should be funded to address the anticipated growth and to make sure that more children do not end up in detention because of lack of community options.

- Provide funding for short-term placement beds – Interviewees from both DJJ and AOC identified the need for short-term (one or two night) placements for kids who temporarily cannot be in their homes but should not be placed in a detention facility. In the past, both DJJ and AOC relied on foster homes for these types of placements, but with the reduction in available foster homes statewide, the desire to keep children close to home, and the inconsistent and variable need for these types of placements, children often end up in detention facilities. Providing funding to support the availability of these types of placements, especially in the rural areas of the state, would provide a consistent and reliable resource that both DJJ and AOC could access and would help to keep kids out of detention.

- Evaluate and, if warranted, expand day treatment programs – DJJ operates five-day treatment programs and contracts for 19 others across the state. These programs combine education and therapeutic services for youth between the ages of 12 and 18 and provide important support so youth can stay in their communities or successfully reintegrate after stepping down from a residential program. These programs are an important part of the community-based system of services available to youth, and their evaluation for effectiveness, and further expansion to serve more youth and communities if warranted, should be considered.

- Support additional data collection for program evaluationSupport additional data collection for program evaluation – The collection and use of data to evaluate the effectiveness of programming often falls by the wayside when overall funding is not sufficient to provide services. The lack of this type of data was noted in two of the OJP studies referenced earlier and was also identified by several people we interviewed for this report. Rigorous program evaluation is important and necessary to ensure that scarce resources are being used in the most efficient and effective manner.

- Provide funding to AOC to address a current gap in the system – case management for youth who are monitored by the court in the community but not the responsibility of DJJ – AOC is responsible for the entire front end of the juvenile system; they are on call 24-7 for any youth taken into custody by law enforcement, work with youth and their families participating in diversion, process all juvenile complaints, and they monitor informal adjustments imposed by the courts – all duties that were significantly expanded by the passage of SB 200. Yet they have received no additional funding to support these functions.

In this regard, one disposition used quite frequently by the courts is community release with parental supervision.44 In these circumstances, CDWs are not involved because the case is not one that qualifies for diversion, and DJJ is not involved because the youth is not committed to DJJ or ordered to be supervised by DJJ. With no case management from DJJ or a CDW, there is a lack of coordination and access to needed services, and assistance obtaining them does not exist. Lack of support at this level can lead to youth moving further into the system, requiring more expensive and invasive interventions.

AOC is attempting to address this gap in case management and services through the implementation of pilot programs in some judicial districts. However, without additional resources AOC lacks the financial ability to take these programs and services statewide.

- Provide funding to allow agencies involved in the juvenile justice system to effectively track recidivism and to share information effectively – Although there is some good and useful data available, particularly through AOC, the various data systems used by agencies involved in the juvenile justice system are not compatible, and it is therefore difficult to trace youth across systems and for agencies to develop a comprehensive overall picture. In addition, although there is some recidivism data available, it is limited and is not widely collected or analyzed. Having more robust recidivism data tied to resources and programming would provide crucial information to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and services. Both AOC and DJJ are currently upgrading and standardizing their data systems, but both will need financial support to maintain the systems at the level necessary to collect and share data, evaluate programs, and provide the information necessary to efficiently use resources.

- Prioritize funding for school-based mental health services in addition to funding for more school police officers – Many children who have complaints filed against them are experiencing mental health challenges that contribute to their behavior. And Kentucky’s children are experiencing a mental health crisis. Data from the 2023 Youth Behavioral Risk Surveillance System indicates that 42% of Kentucky’s high school students felt sad or hopeless, an increase from 37% in 2019. In addition, 30% of high school students in Kentucky, including 41% of girls, and 54% of LGBTQ+ students reported that their mental health was most of the time or not always good.45 Yet in the 2024-2026 state budget, the General Assembly prioritized additional funding for school resource officers over providing more support for mental health services.

The General Assembly provided $7.4 million in each year of the 2024-2026 biennium to the Department of Education to support school-based mental health service provider positions on a reimbursement basis. When that amount is divided among Kentucky’s 170 school districts, according to the distribution formula established by The Kentucky Center for School Safety, the amount received by each school district is only $43,096.46 That does not even cover the cost of one professional in one school. A recent report issued by the School Safety Marshal identified that almost 9% of Kentucky schools do not have a certified school counselor, and 46% of schools that do not meet the state target of one counselor for every 250 students.47

Yet in the same budget, the General Assembly provided $16.5 million in fiscal year 2025 and $18 million in fiscal year 2026 to fund salaries for school resource officers.48 The number of school resource officers in Kentucky’s schools has increased from 263 in fiscal year 2015 to 830 in fiscal year 2024.49

Expanding the availability of school-mental health services will require more than just additional funding, however, because of a severe shortage of qualified mental health professionals in Kentucky and across the country, and the needs in Kentucky extend beyond schools. A strategy should be developed with colleges and universities to train more mental health professionals, and requirements and regulations that allow mental health professionals to provide services via telehealth and across state lines should be examined to potentially expand the available resources.50

- Explore the use of new, cost-effective approaches to increase the availability of community services and programming – Some of the barriers to the availability of more community services can be addressed in a cost-effective manner by exploring new options. Creative ways to address transportation barriers include partnering with schools to provide more services and programs there, exploring the use of existing rural transportation providers to transport children and their parents to services, or employing a company like HopSkipDrive to provide transportation services.51 Transportation barriers can also be overcome using technology to provide some services remotely such as mental health counseling and training programs. Addressing transportation issues may also help providers serve larger areas in the rural parts of Kentucky because children can come from further away to access the services.

Recently enacted legislation threatens the progress made under SB 200

Despite data clearly illustrating the success of SB 200’s efforts in diverting children away from the courts and keeping them in community without harming public safety, legislation passed by the General Assembly in recent years has moved Kentucky in the opposite direction. False narratives of a juvenile crime wave and “super predator” rhetoric have resulted in new legislation targeted at justice-involved youth, aiming to make penalties harsher for them.

In addition, punitive legislation to address chronic absenteeism that all states continue to experience following the COVID school closures will likely result in many children who miss school moving deeper into the system rather than being diverted before the court becomes involved.52

Two recent policy changes are of particular concern to the goals and purposes of SB 200:

- “Mandatory detention” for all children charged with a “violent felony offense”53

Effective July 1, 2024, children charged with a violent felony offense must be detained for up to 48 hours pending a detention hearing in front of a judge.54 Previously, the decision whether to detain a child at intake was made by a judge prior to the detention hearing, in consultation with law enforcement and the CDW, with the benefit of all the information obtained by the CDW during the intake process about the child’s situation and the circumstances of the charge.

Under the revised language, the decision about whether a child will be detained pending a detention hearing is still made by a judge, but the revised statutory language provides no discretion for the judge if the law enforcement officer has charged the child with a violent felony offense. This provision essentially requires that all children with certain charges be treated the same, regardless of their personal circumstances or situation.

Although this provision has been in effect only a short time, data presented by AOC to the JJOC at its November 2024 meeting identified a concerning uptick in the detention of youth taken into custody by law enforcement pending a detention hearing, when comparing the period from July 1, 2024, through Oct. 28, 2024, to the comparable period for fiscal year 2023. AOC reported that the number of children detained had increased by 17% year-over-year, with a 30% increase in Jefferson County and a 14% increase overall in Kentucky’s other 119 counties, although total complaints filed had only increased 6%. The report also noted that there were 216 complaints resulting in detention in September of 2024, representing the highest number in a single month since September of 2013.55

Given the well-documented harms of even one day in detention for a child, the mandatory hold provision will result in significant harm to children, as well as increasing the number of children in Kentucky’s understaffed juvenile detention facilities.56

- Harsher treatment for kids missing school

House Bill (HB) 611 passed by the 2024 General Assembly, which harshens punishments for status offenses, will have far-reaching consequences and could significantly reverse many of the gains that have been made for this group of offenses under SB 200.57HB 611 completely bypasses the process established by SB 200 to automatically divert status offenders away from the court system for children who are in the 6th through 12th grades and have missed 15 or more days of school. School Directors of Pupil Personnel (DPPs) can file habitual truancy complaints with the CDW after a child has six unexcused absences.58 HB 611 requires DPPs to notify the county attorney when a child has 15 unexcused absences. The county attorney may then override the child’s ability to participate in diversion and proceed directly to court or may refer the case to the CDW to enter into a diversion agreement, which must include a provision that if the child has four unexcused absences after signing the agreement, formal court action will be filed. Prior to the passage of HB 611, prosecutors did not have the ability to override the diversion process for children accused of status offenses.

This legislation is concerning for several reasons. The revised provisions will apply to virtually all truancy complaints, because DPPs typically do not file a complaint until a child has missed at least 15 days of school.59 And because of the complicated nature of, and time required to address, the issues that may have led to a child being absent from school, it is likely that a high percentage of the cases that are referred for diversion will end up with a formal court referral. This is due to the mandatory provision in the agreement requiring such action if there are more than four unexcused absences after the diversion agreement is entered into, reversing the significant progress that has been made in the diversion of status cases.

This requirement also effectively prevents the use of graduated sanctions to address noncompliance and will also likely result in the increased detention of status offenders, because a child who is on diversion for truancy cannot be sent to detention, but a child who violates a valid court order can.

“Chronic absenteeism” has been a significant issue following the COVID school closures all across the country, with the rate of chronically absent students (those missing 10% or more of school days) almost doubling compared to before the pandemic.60 Kentucky’s chronic absentee rate remains higher than many states at 28% for the 2023-2024 school year, but it has come down some since the peak of 30% in the 2022-2023 school year.61 Addressing chronic absenteeism has been difficult for schools across the country, and has complex causes. Taking kids and families to court is not the solution.

Recommendations

- Reverse the harmful juvenile justice changes made during recent legislative sessions – The punitive changes in the laws discussed above should be reversed because their focus on punishment will make it more difficult for children and families to move forward in a positive direction. Discretion should be restored to judges about whether to detain a child at intake. And the required diversion of children who miss more than 15 days of school should be restored with additional investment in community resources to increase their likelihood of success.

- Instead of bringing chronically absent kids before the courts, invest in strategies that strengthen relationships – Effective strategies that have been identified to bring kids back to school rely on creating and strengthening trusting relationships between schools and families and identifying and addressing barriers to attendance. They also rely on using data to focus resources on children and families within groups that experience higher rates of absenteeism including those who are homeless, qualify for free or reduced lunch or have high needs.62 They do not focus on pushing children further into the criminal legal system as HB 611 does. Rather than effectively addressing absenteeism, deeper court involvement will likely further alienate families who already lack trust in systems, making it more difficult to reengage and connect them with school.

Kentucky still allows too many children to be securely detained

An overwhelming and ever-increasing body of evidence shows that the incarceration of youth in secure detention facilities, even for a short period of time, substantially increases the odds they will move deeper into the justice system, reduces the likelihood they will graduate from high school, and exacerbates what are, for many youths, existing physical and mental health issues.63

Children who are charged with status offenses have not committed a crime and are exhibiting behaviors that require support and treatment in the community rather than confinement. Kentucky statutes currently allow the detention of a child in a secure juvenile detention facility for up to 30 days as a punishment if the child fails to comply with a valid court order.64 As currently written, this provision applies to both public offenders and status offenders.65 This Kentucky law is counter to the widely recognized purpose of secure detention, which is to temporarily house youth who a judge determines is at high risk for reoffending before their case can be heard, or who are likely to not appear in court.66

By far, the largest number of complaints for a status offense are filed by school districts for habitual truancy. These cases are primarily addressed through diversion before a court case is filed. However, as described above, changes in the law in 2024 will make it more likely that children who have missed a lot of school will end up in court, which means that more children will be subject to valid court orders with secure detention as a possible punishment for violation. Incarcerating a child whose only offense is missing school is both traumatizing and counterproductive. A child in detention is not attending their regular school or working on the trusting relationships that will help to create connection and a feeling of safety in their normal environment.67 As such, rather than helping children and families address the issues that resulted in their lack of attendance, which should be the goal of truancy intervention, incarceration as a punishment moves the child in the opposite direction and makes it less likely the child will be able to succeed.

Likewise, harshly punishing parents when their children are chronically absent adds additional stress to families that in many cases are already facing multiple issues, worsening the situation and creating additional barriers to success. Parents should be involved in addressing their child’s chronic absenteeism, but the purpose of the involvement should be to build trust and support and to help address barriers, not to add more trauma and stress. The Parent Engagement Meeting Program, established by the Cabinet for Health and Family Services, is an example of an alternative, positive approach to addressing chronic absenteeism for younger children. The program currently operates in 23 counties, with a goal of preventing family involvement with DCBS and the courts for educational neglect by using a proactive approach of meeting with parents to develop positive relationships and a collaborative plan to address issues impacting their child’s school attendance. In the 2022-2023 academic year, the program served 406 children in Jefferson County with an 84% success rate, and 786 children in the other 22 counties with an 87% success rate.68

Recommendations

- Amend the law to prohibit the secure detention of children who commit status offenses

- Provide help rather than harsh punishment to parents whose children are missing school – Rather than punishing parents, programs like the Parent Engagement Meeting Program described above should be expanded and other similar programs should be explored that help to build connections and relationships with schools. Expansion of this program as an effective approach to addressing absenteeism should be explored as a more cost-effective and effective way to address truancy.

- Reduce the use of detention for children who are charged with public offenses – Detention should only be used for public offenders in circumstances where there is clear evidence that there are no other acceptable alternatives. In all of the research that has been conducted, there is no evidence that secure detention is an effective deterrent to crime, an effective way to encourage children to move away from criminal behavior, or a way to enhance public safety.

Ethnic and racial disproportionality persists and, in some cases, has worsened

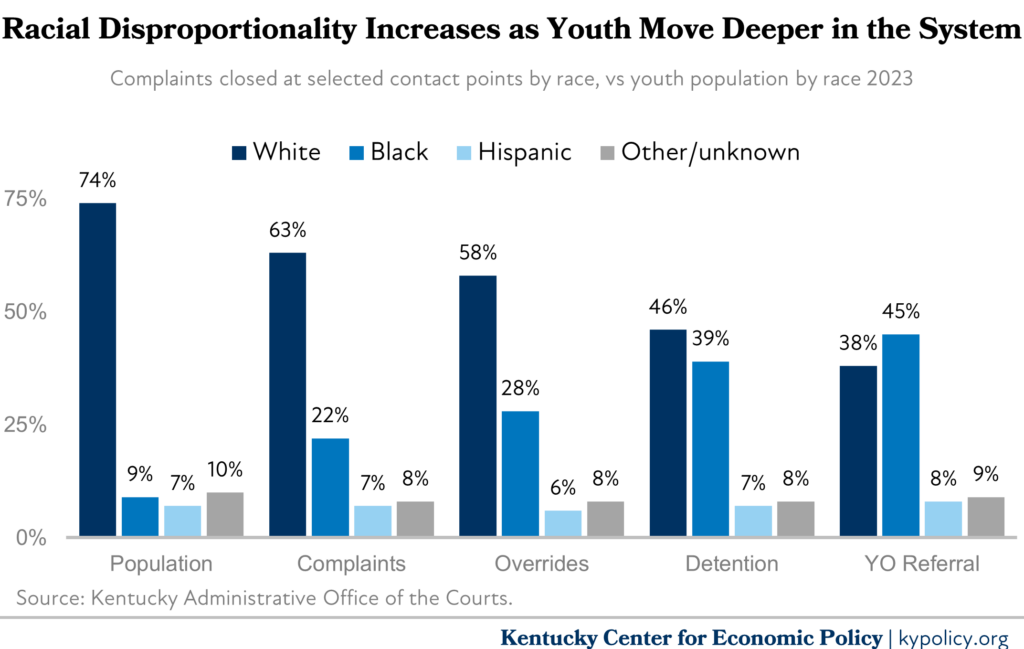

Kentucky, like all other states, has significant and persistent racial and ethnic disproportionality within its juvenile justice system. The reforms of SB 200 significantly reduced the overall number of children entering the juvenile justice system, but the children who become more deeply involved are disproportionately Black, as illustrated by the graph below.

The further children move into the system, the deeper the racial and ethnic disproportionality is. In the chart above, Black youth make up 9% of the total state youth population, and yet:

- At the first point of contact – the filing of a complaint – 22% were filed against Black youth;

- At the point where a prosecutor or judge can exercise their right to override a recommendation for diversion, 28% of those overrides were for Black youth;

- At the point where a judge determines whether a child should be detained or remain in the community pending a hearing, 39% of the children detained were Black youth; and

- Of all children whose cases were eligible to be waived to adult court – the most serious consequence for a child accused of committing a crime (referred to above as “YO Referral”), resulting in them being tried as adults – 46% were Black youth.69

The significance of this disproportionality cannot be overstated. Each decision made as a child moves through the system impacts the next and the deeper children move into the system, the more likely that child is Black.

Based on 2021 data, Black youth are 9.8 times more likely to be held in a juvenile facility than their white peers, and racial disproportionality of children detained or committed in Kentucky’s juvenile system increased by 92% between 2011 and 2021, the 4th-largest increase in the nation.70

Although the total number of commitments of Black, Biracial and Hispanic children to DJJ went down between 2014 and 2023 (236 compared to 190), the percentage of all committed children who are Black, Biracial or Hispanic increased from 47% to 61%. The same pattern plays out in the total number of Black, Biracial and Hispanic children probated to DJJ. The overall number of children was also lower comparing 2014 to 2023 (357 to 288), but the percentage of all probated children that were Black, Biracial or Hispanic increased from 34% to 53%.

The disproportionality begins before children even reach the courts. Data provided in the 2023-2024 Safe Schools Annual Statistical Report demonstrate that racial disproportionalities are also present in the schools, with Black students making up 10.8% of the population but being involved in 30.8% of behavior incidents.71

These differences have become more pronounced over time despite efforts taken by AOC to address and reduce them, including the publication of a comprehensive guide and trainings around the recommendations in the guide.72 Senator Westerfield introduced legislation in the 2016, 2017, and 2019 legislative sessions that included provisions to collect more data that would allow a better understanding of racial and ethnic disparities, but none of the bills advanced.73

Recommendation

- Use local data to understand the scope of the disproportionality and its impact on disparities and then make a plan to address them – Racial and ethnic disproportionality in the juvenile system has been discussed, debated and reported on in Kentucky frequently over the past 10 years; however, the conversations, debates and reporting have not changed the outcomes.74 It is time for a renewed focus on addressing these issues, and the work to do this begins with an evaluation of data and outcomes at the local level. Data within each judicial district should be reviewed, beginning with the decision to charge a child all the way through the ultimate disposition of cases to identify where disproportionality exists. Once disproportionality has been identified, practices and procedures should be examined to identify disparities.75 It is often the case that practices and procedures that appear facially neutral have disparate impacts that are not identified unless those practices and procedures are intentionally and critically examined. The review and analysis should involve all agencies and entities that participate in FAIR Teams and should be continuous and ongoing, with a goal of using the data to inform decision making that will actually change the trajectory for children of color through the execution of a strategic plan with actionable goals. The AOC guide mentioned above is an excellent resource for guiding this work. Other strategies that have shown some success include many of the recommendations made above – investing in community programs, increasing diversion, providing more services to youth returning to the community and reducing the use of secure detention.76

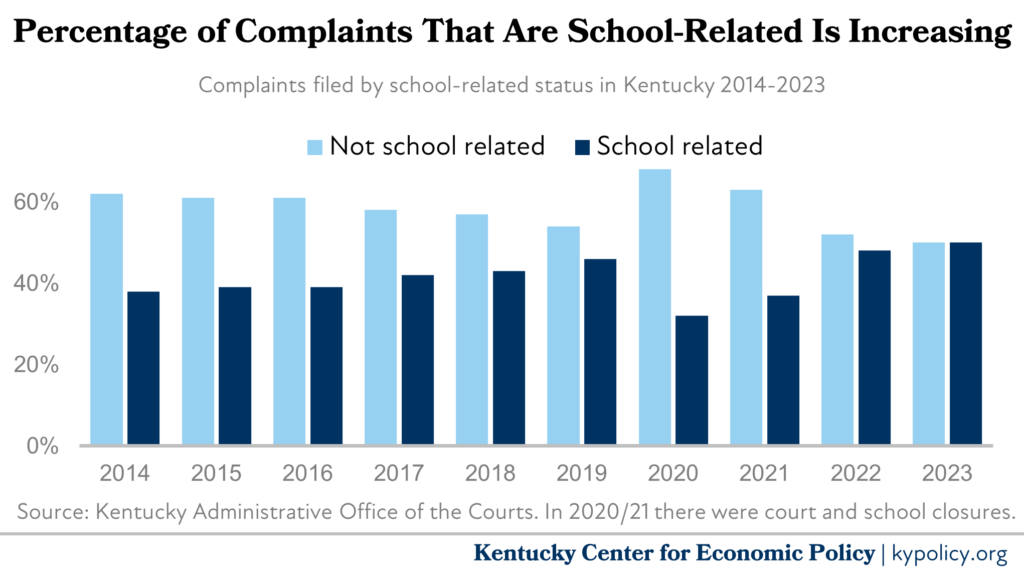

Complaints from schools are increasing

Data shows that complaints against youth originating from schools have increased over the past 10 years, from 38% in 2014 to 50% in 2023, as illustrated in the graph below. This trend is troubling, and additional research should be conducted to better understand why this is happening, including looking at data by school district to identify districts where issues may be more prevalent.

The 2023-2024 School Safety Statistical Report published by the Kentucky Department of Education notes that: “The involvement of a school resource officer (SRO) is the most frequently deployed legal sanction representing 62.3% of all legal sanctions. This is followed by charges (22.9%) and calls to police (6.9%). The use of legal sanctions has grown over time. SROs were involved in 5,303 behavior events, which is an increase since 2019-2020 but corelates with an increase of SRO presence in schools as required by the 2019 Safe Schools and Resiliency Act.”77

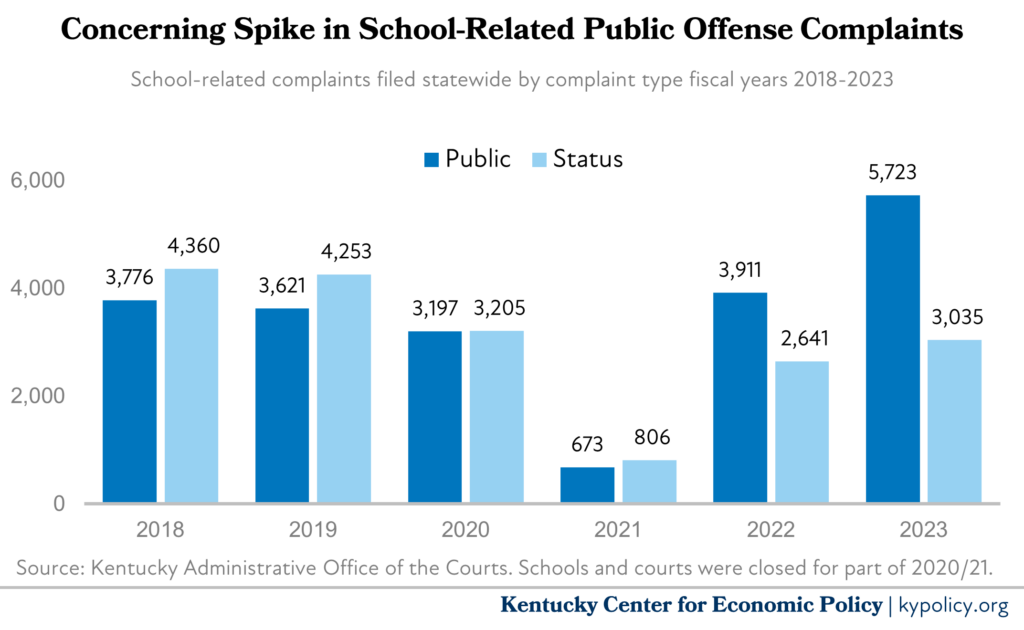

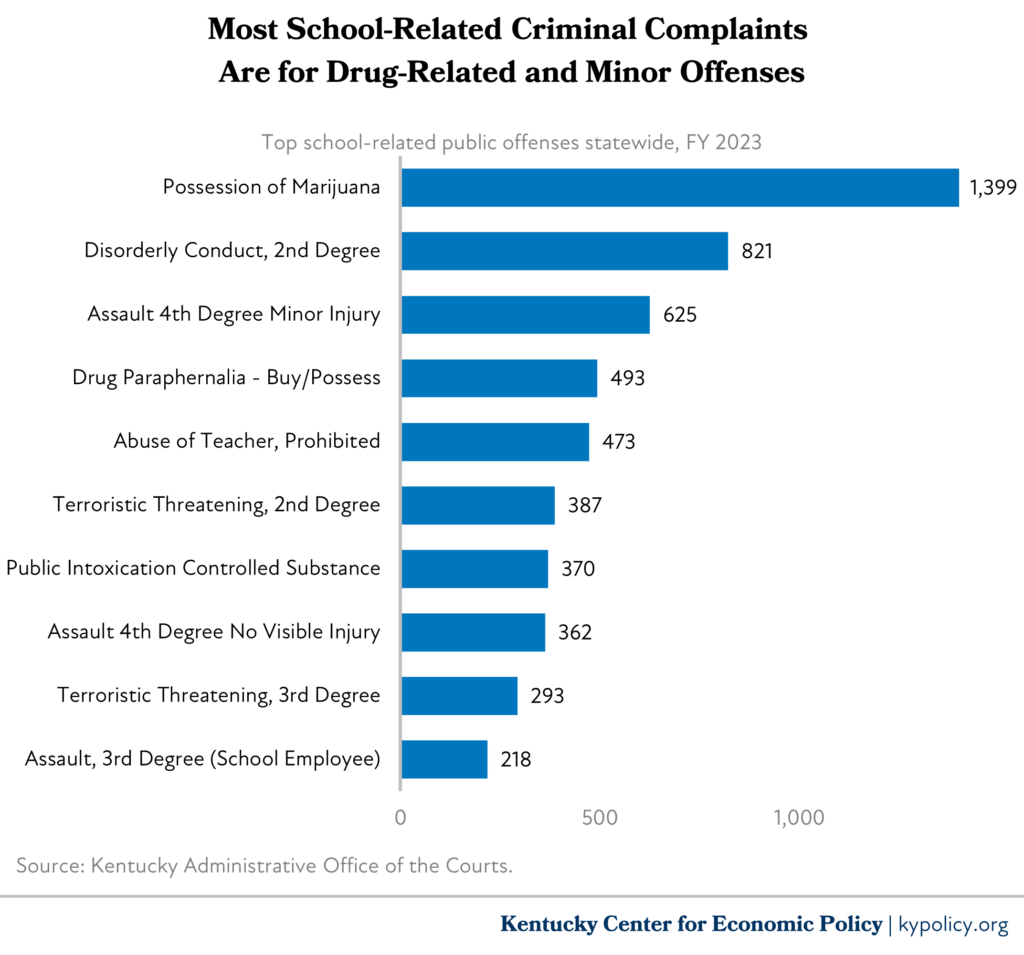

Recent rigorous research on the impact of SROs in schools found that their presence increases the likelihood that children will be arrested and referred to the criminal legal system for minor offenses that would have otherwise been handled by school administrators. Their presence also results in increased weapons and drug-related offenses, an increase in complaints for serious violent offenses, an increased use of exclusionary disciplinary actions and an increase in the severity in school responses.78 As illustrated in the two graphs below, there has been a concerning spike in the number of public offense complaints coming from schools in 2023, and the most common school-related public offenses for which complaints were filed are minor and drug-related offenses.

Although many more schools now have SROs, the expectations, requirements and employers of the officers differ across school districts with some being employed by the district and others being employed by the local police department or sheriff. Research shows that schools that have SROs that focus primarily on law enforcement file more charges than schools whose SROs focus on building relationships and mentoring.79 Given the differing structures and employing agencies, it is crucial that data be collected and analyzed at the school district level to better understand the reasons behind increasing school complaints.

Recommendations

- Require the collection of more data from schools to understand and address the growing number of complaints – Statutes establishing parameters for the collection and reporting of school data do not currently require schools to report detailed information about legal sanctions imposed against students.80 To better understand the nature of complaints emanating from schools, the following data should be collected: For each charge or complaint, whether through the school resource officer, DPP, local police or any other source, identification of who filed the complaint, the age, grade, race, ethnicity and gender of the child, the specific charges filed, and the outcome of the charges being filed. In addition, similar data should be collected and reported for behavioral events that do not rise to the level of charges.

- Collect data that will allow an ongoing analysis and monitoring of the relationship between more SROs and the increase of complaints from schools –Data should include the number of officers in each school, the employing entity of each officer, the training each officer has received, the number and nature of disciplinary actions taken or filed by each officer, including the age, race, ethnicity and sex of each child against who a disciplinary action was taken, and how each disciplinary action was resolved.

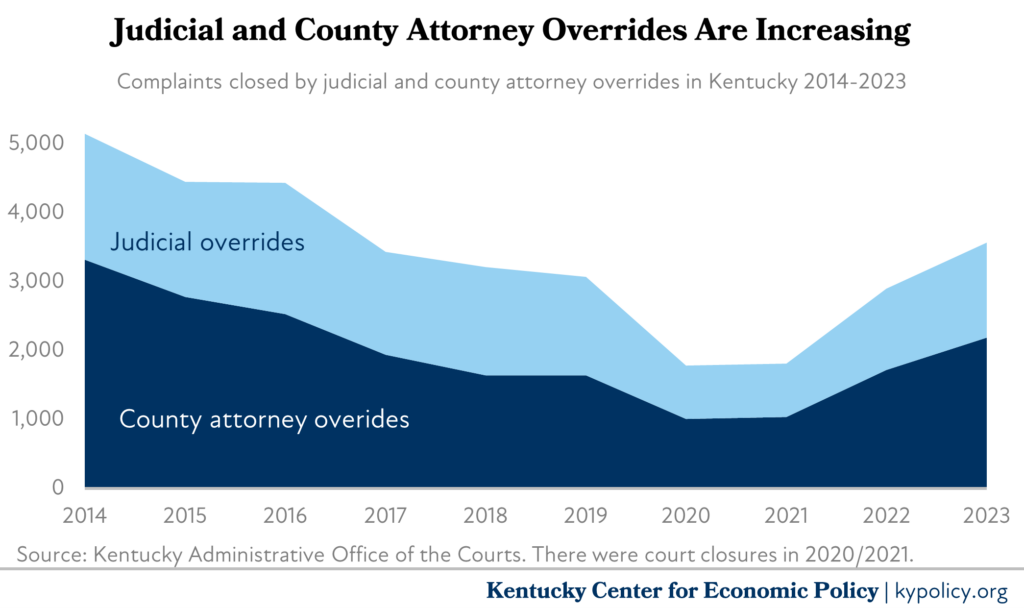

Prosecutorial and judicial overrides are increasing, causing more children to move deeper into the system

Judicial and prosecutorial overrides result in children that would otherwise be eligible for diversion being processed through the court instead. These overrides have fallen from 23% to 19% of complaints filed comparing calendar year 2014 to calendar year 2023 overall, but they are still very high and are increasing.81

Over the past two years, there has been a significant increase in what had been a declining trend of the use of prosecutorial and judicial overrides in misdemeanor cases. There was an increase of 54% from fiscal year 2022 to fiscal year 2023 (657 to 1,011), and another increase of 11% from fiscal year 2023 to fiscal year 2024 (1,011 to 1,125) in the use of prosecutorial overrides and increases of 18% and 17% respectively in the use of judicial overrides.

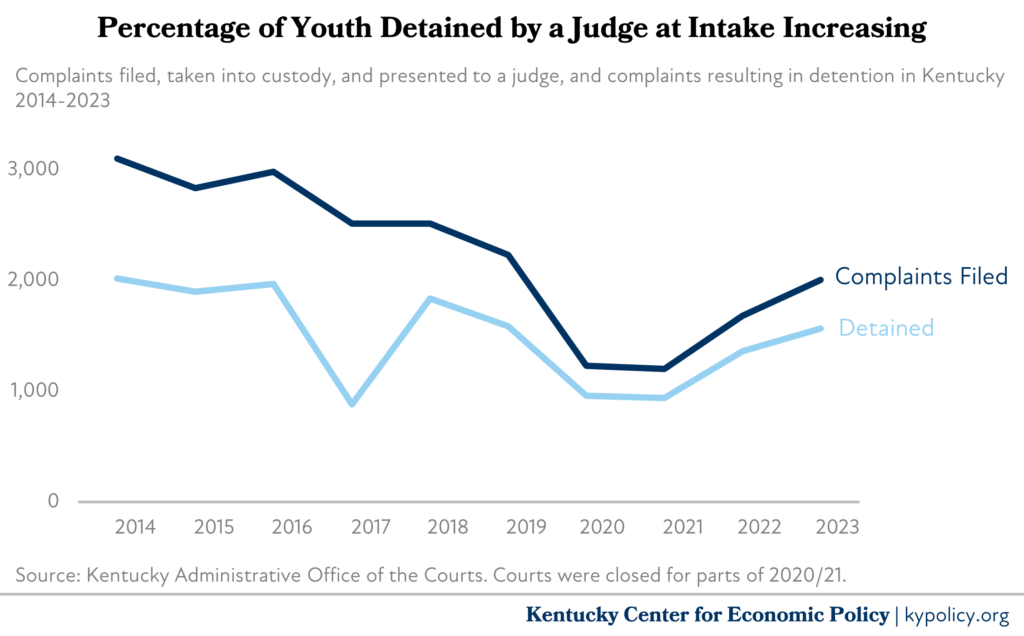

Concerning increases in the percentage of youth detained at intake

Another concerning trend revealed by the data is an increase in the percentage of youth detained at intake. As can be seen in the graph below, the number of youth taken into custody has declined by 35% between 2014 and 2023; however, among those youth, the number whose cases were presented to a judge and were securely detained has increased from 65% in 2014 to 78% in 2023. Further, of the youth securely detained, the percentage of Black and Hispanic youth increased from 38% to 46%, while the number of White youth decreased from 59% to 46%. Given the harms of secure detention, it is important to understand why this increase has occurred.

Recommendation

- To better understand both the increasing use of overrides and the increase in secure detention at intake local data should be requested and reviewed – It is often the case that trends that appear in statewide data are concentrated in just a few jurisdictions, so it is always important to request and review data at the local level. Data requested should include the age, race, ethnicity, and sex of each child, the charges filed, and the reason cited for override or detention, if one was given. If specific jurisdictions are identified as having overrides or intake detentions that occur at a higher level, interviews should be conducted with the CDW, judge and prosecutor in those jurisdictions to better understand why overrides are being used or children are being detained to determine if there are services or programs that could be implemented that are less intrusive.

Conclusion

It is important to acknowledge and celebrate the significant impact that SB 200 had over the past 10 years in meaningfully reducing the number of children who become involved with the juvenile justice system. DJJ and AOC have accomplished much without the promised additional investment in community services and programs, and they should be recognized for their successes.

Yet there is still much work to be done. To continue the forward progress of SB 200, the General Assembly should refocus its efforts to support programs and services that strengthen communities, children and families, rather than policies that break them apart through harshening penalties and increasing incarceration. For the infrastructure established by SB 200 to work as intended, the investments in community programming made in the 2024-2026 budget should be maintained and expanded. And to ensure that money is well spent, more data should be collected, analyzed, and reported to understand which programs and services are working and which are not. Further, data should be regularly requested and analyzed at the local level to identify and better understand areas of the state where additional investment and focus may be needed so that the use of funds can be better targeted. Finally, because Kentucky has made very little progress in addressing the significant racial and ethnic disproportionalities that exist throughout the system, a renewed focus is necessary. More and better data should be collected to increase understanding of why the disproportionalities have worsened, why the efforts undertaken so far have not worked, and what can be done moving forward.

Appendix

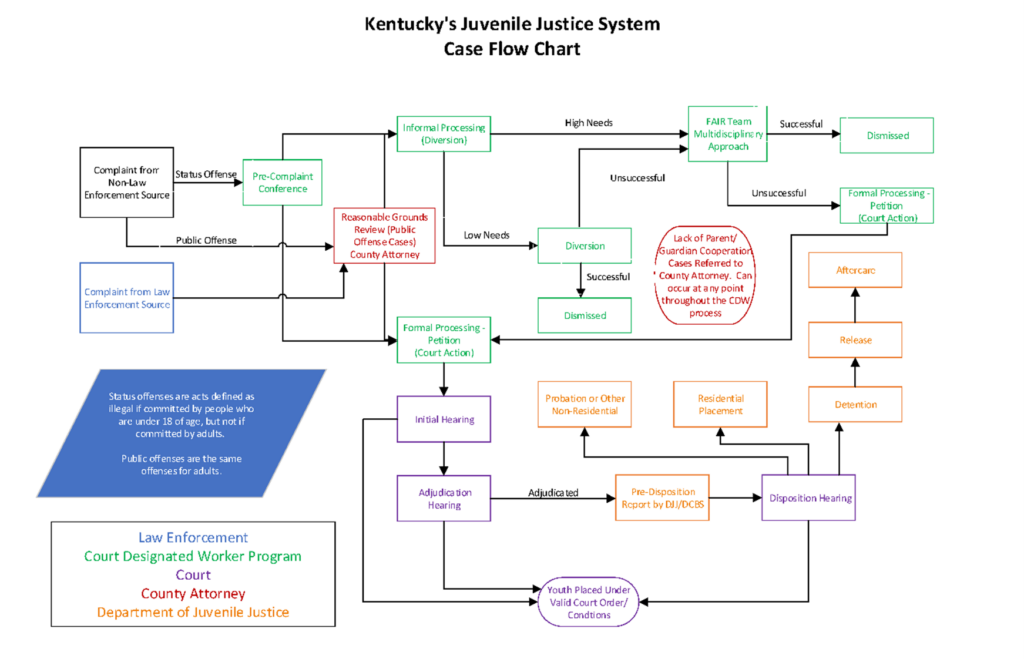

This flow chart, prepared by AOC for a presentation before the Juvenile Justice Advisory Committee, generally illustrates the movement of cases through the juvenile justice system.82

- 2012 Ky Acts Ch 37, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/12RS/documents/0037.pdf, extended by 2013 KY Acts Ch 9, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/13RS/documents/0009.pdf.

- “Report Of The 2013 Task Force On The Unified Juvenile Code,” Legislative Research Commission, December 2013, https://legislature.ky.gov/LRC/Publications/Research%20Memoranda/RM514.pdf. For more detailed information about the findings of the task force, see also Pew Charitable Trusts, “Kentucky’s 2014 Juvenile Justice Reform,” July 2014, https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2014/07/psppkyjuvenilejusticereformbriefjuly2014.pdf.

- Conditions of community supervision can include requirements such as attending school, being home before an established curfew, attending any required appointments, participating in community services and making restitution if ordered by a court.

- Children who have public offenses and are committed become the responsibility of DJJ, while children who have status offenses and are committed are the responsibility of DCBS.

- References to support these statements that are provided in the task force report are as follows: D.S. Nagin, F.T. Cullen and C.L. Jonson, “Imprisonment and Reoffending, Crime and Justice (2009), pp. 115-200. P. Smith, C. Goggin and P. Gendreau, “The Effects of Prison Sentences and Intermediate Sanctions on Recidivism: General Effects and Individual Differences,” Solicitor General of Canada, 2002. P. Villettaz, M. Killias and I. Zoder, “The Effects of Custodial vs. Noncustodial Sentences on Re-offending: A Systematic Review of the State of Knowledge,” The Campbell Collaboration, 2006. E.P. Mulvey, L. Steinberg, A.R. Piquero, M. Besana, J. Fagan, C. Schubert and E. Cauffman, “Trajectories of Desistance and Continuity in Antisocial Behavior Following Court Adjudication Among Serious Adolescent Offenders,” Development and Psychopathology, (2010), pp. 453–475. T.A. Loughran, E.P. Mulvey, C.A. Schubert, J. Fagan, A.R. Piquero and S.H. Losoya, “Estimating a Dose-Response Relationship Between Length of Stay and Future Recidivism in Serious Juvenile Offenders,” Criminology, (2009), pp. 669-740. D.A. Andrews, I. Zinger, R.D. Hoge, J. Bonta, P. Gendreau and F.T. Cullen, “Does Correctional Treatment Work? A Clinically Relevant and Psychologically Informed Meta-Analysis,” Criminology, (1990), pp. 369-404. C. Dowden, and D.A. Andrews, “What Works in Young Offender Treatment: A Meta-Analysis,” Forum on Corrections Research, (1999), pp. 21-24.

- 2014 Ky Acts Ch 132, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/14RS/documents/0132.pdf.

- Several of the people we interviewed identified school districts as one of the primary opponents to the reforms.

- KRS 605.035, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=55115. FAIR teams can include up to 15 members, with required representation from the Court Designated Worker program, the community mental health center or the regional interagency council, the Cabinet for Health and Family Services, the county attorney’s office, the Department of Public Advocacy, the local public school district, and local law enforcement. FAIR teams can also include other people interested in juvenile justice issues.

- KRS 635.060, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=53974.

- KRS 635.060, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=53974. Following the passage of SB 200 DJJ is required to use graduated sanctions in response to violations of community supervision before a child is removed from the community. See Department of Juvenile Justice, “Kentucky Department of Juvenile Justice Policy Manual,” Community Supervision, DJJ Policy Number DJJ 605, https://djj.ky.gov/Policy%20Manual/Documents/600series/DJJ%20605%20Community%20Supervision.pdf.

- KRS 605.100, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=43504. KRS 610.030, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=55377.

- KRS 15A.063, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=53538.

- KRS 15A.061, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=53537. KRS 605.020, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=43962.

- KRS 15A.062, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=43480.

- KRS 600.010, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=43498.

- Crime and Justice Institute, ”Kentucky’s Senate Bill 200: Comprehensive Reform Implementation Successes,” 2017, https://www.crj.org/assets/2017/08/KY_SB200_Infographic_FINAL.pdf.

- Continued involvement of the Crime and Justice Institute and Pew Charitable Trusts was supported with funding from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention’s Comprehensive Juvenile Justise System Improvement Initiative. See: Crime and Justice Institute, ”Implementing Comprehensive Juvenile Justice Improvement in Kentucky,” October 2017, https://www.crj.org/assets/2018/06/KY-Brief-v9-10-25-17_UPDATED.pdf and The Pew Charitable Trusts, ”Kentucky’s 2014 Juvenile Justice Reform,” July 2014, https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2014/07/psppkyjuvenilejusticereformbriefjuly2014.pdf.

- Suzanne O. Kassa, Sarah Vidal, Kristi Meadows, Megan Foster and Nathan Lowe, ”Kentucky Juvenile Justice Reform Evaluation: Implementation Evaluation Report,” National Institute of Justice, December 2019, https://nij.ojp.gov/library/publications/kentucky-juvenile-justice-reform-evaluation-implementation-evaluation-report. Sarah Vidal, Kathryn Kulbicki, Trey Arthur, Suzanne Kassa, Michele Harmon, Megan Foster and Nathan Lowe, ”Kentucky Juvenile Justice Reform Evaluation: Assessment of Community-Based Services for Justice Involved Youth,” National Institute of Justice, January 2020, https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/library/publications/kentucky-juvenile-justice-reform-evaluation-assessment-community-based. Sarah Vidal, Elizabeth Petragalia, Trey Arthur, Michelle Harmon, Megan Foster and Nathan Lowe, ”Kentucky Juvenile Justice Reform Evaluation: Assessing the Effects of SB 200 on Youth Dispositional Outcomes and Racial and Ethnic Disparities,” U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, September 2020, https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/library/publications/kentucky-juvenile-justice-reform-evaluation-assessing-effects-sb-200-youth. Samantha Harvell, Leah Skala, Daniel Lawrence, Robin Olsen and Constance Hull, ”Assessing Juvenile Diversion Reforms in Kentucky,” Urban Institute, Sept. 17, 2020, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/assessing-juvenile-diversion-reforms-kentucky .

- Finding no reduction in out-of-home placements despite reduced commitments, the report’s authors surmised that a lack of community-based services that meet the needs of high risk and high needs youth may be the reason for placements not decreasing, noting that: “As an unfunded mandate, SB 200 significantly changed procedures for working with youth, but did not necessarily provide additional resources that would enhance community-based services. Already facing significant resource limitations, community-based service providers, especially in rural areas, do not have the capacity to meet the needs of youth now going through diversion.” Sarah Vidal, Elizabeth Petragalia, Trey Arthur, Michelle Harmon, Megan Foster, Nathan Lowe, ”Kentucky Juvenile Justice Reform Evaluation: Assessing the Effects of SB 200 on Youth Dispositional Outcomes and Racial and Ethnic Disparities,” U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, September 2020, https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/library/publications/kentucky-juvenile-justice-reform-evaluation-assessing-effects-sb-200-youth.

- 2016 SB 270, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/16rs/sb270.html. 2017 SB 20, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/17rs/SB20.html#SCA1. 2019 SB 20 https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/19rs/sb20.html.