There are two main reasons why shifting from income taxes to sales taxes would be bad for Kentucky:

- Doing so would make our tax system more regressive than it already is (asking lower- and middle-income families to pay an even larger share of their income in taxes to pay for tax cuts for higher-income families;) and

- The shift would further reduce revenue growth that is needed to meet our obligations and invest in our schools, infrastructure and other building blocks of thriving communities.

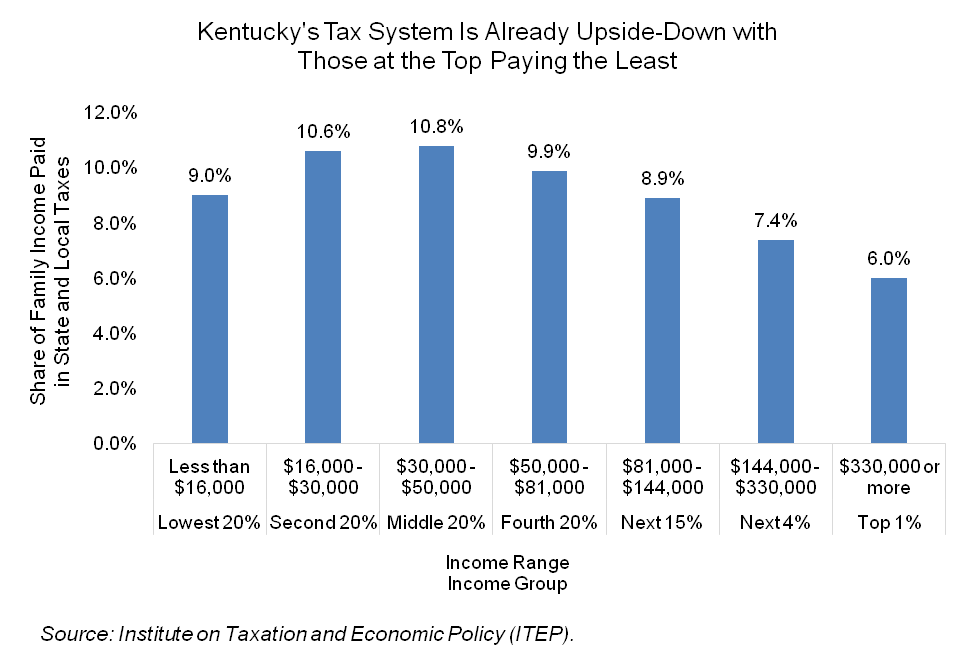

These consequences of upside-down tax shifting are related. When you give huge income tax breaks to people for whom income is growing rapidly and rely more on the sales tax – which disproportionately impacts middle- and low-income families struggling to make ends meet in our top-heavy economy – you shift from imposing taxes on a revenue stream that is growing rapidly to a revenue stream that is not. If revenue doesn’t grow with the economy, additional tax increases or budget cuts will likely be necessary in the near future. And Kentucky’s revenue system is already regressive with the wealthiest 1 percent of Kentuckians paying only 6 percent of their income in total state and local taxes – the least of any income group:

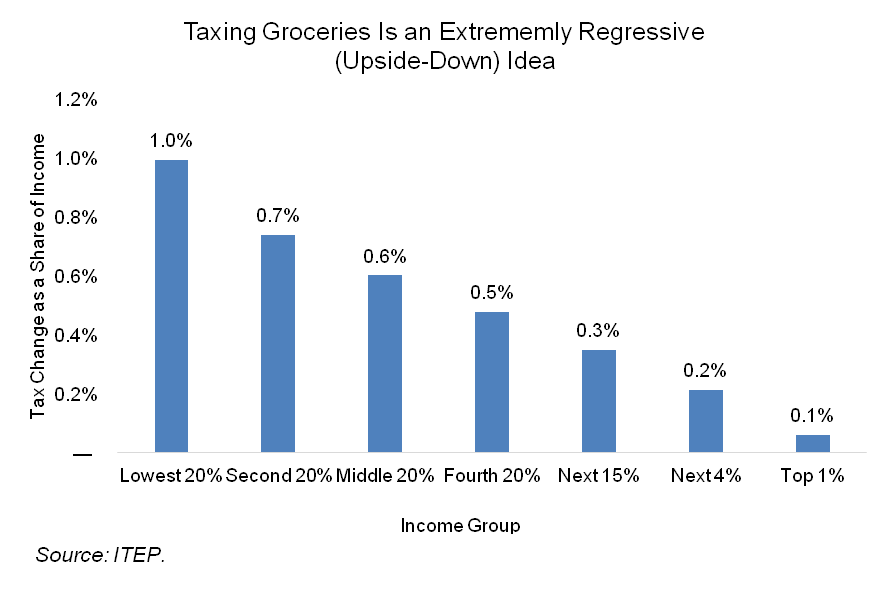

One example of an extremely regressive policy – taxing groceries – has been mentioned recently in conversations about what might be included in a tax proposal from Governor Bevin. Adding groceries to the sales tax base would ask 10 times more as a share of income of families in the poorest 20 percent of incomes compared to the wealthiest 1 percent.

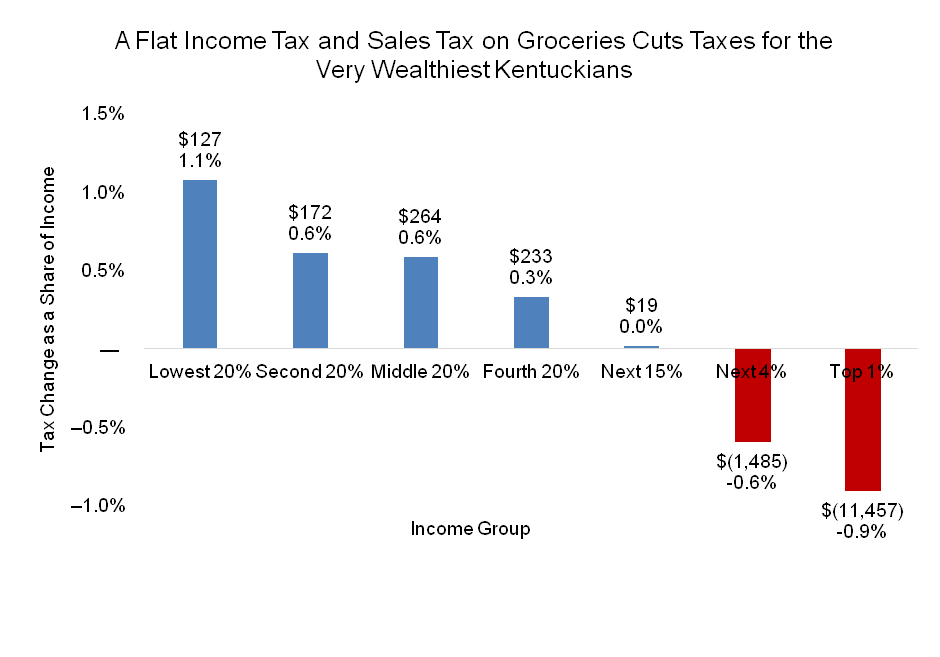

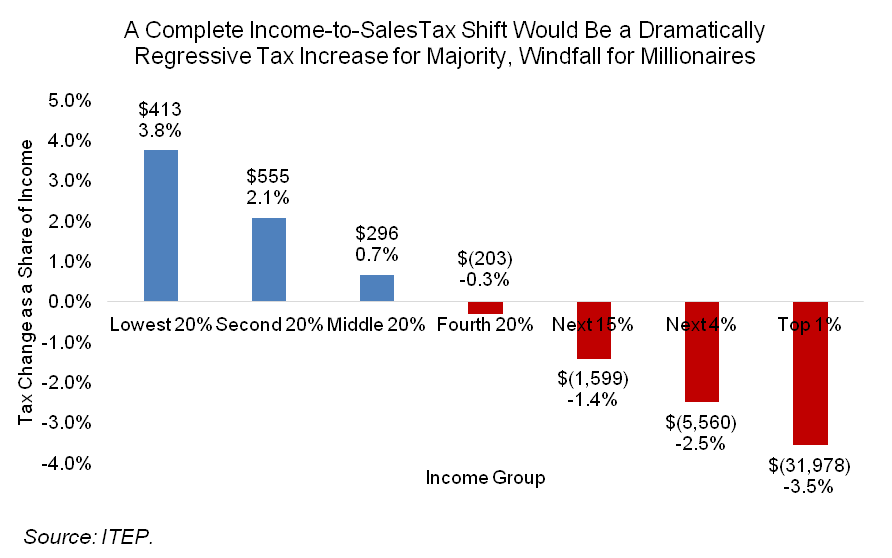

Pair the grocery tax with an income tax cut – even one that “broadens the base to lower rates” – and the shift becomes even more regressive. The chart below illustrates the impact of:

- Adding groceries to the sales tax base at 6 percent (fiscal impact: +$588 million).

- Eliminating itemized deductions and the pension exclusion and compressing income tax brackets and rates to a flat 4 percent tax (fiscal impact: -$594 million).

This shift would be a tax increase for the bottom 80 percent of Kentucky households and a tax cut for the top 5 percent. For the very wealthiest 1 percent whose average income is $1.2 million, the tax cut would average $11,457. In other words, this initially revenue neutral income-to-sales-tax-shift would pay for a huge cut at the top by taxing everyone else more. For the reasons mentioned above, it would also stifle revenue growth down the road.

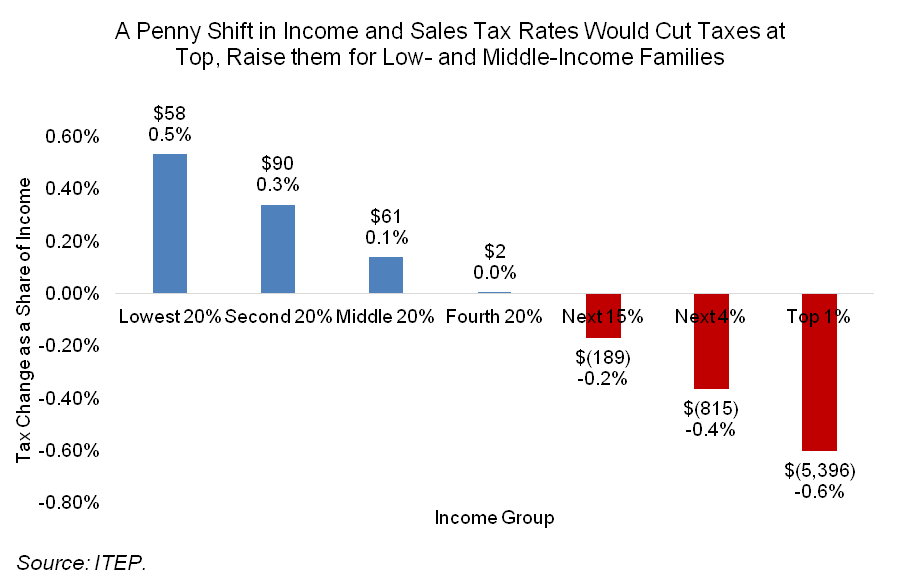

The example above alters both the sales tax and income tax bases, as well as the income tax rate structure. A simple rate cut to the income tax and hike in the sales tax would also constitute a shift from the wealthy onto everyone else. The next chart illustrates the initially revenue-neutral tax shift that would occur if legislators:

- Remove the top two income tax brackets and rates so that the top rate is 5 percent on income over $5,000 instead of 6 percent over $75,000 (fiscal impact: -$554 million).

- Increase the sales tax rate from 6 percent to 7 percent (fiscal impact: +$559 million).

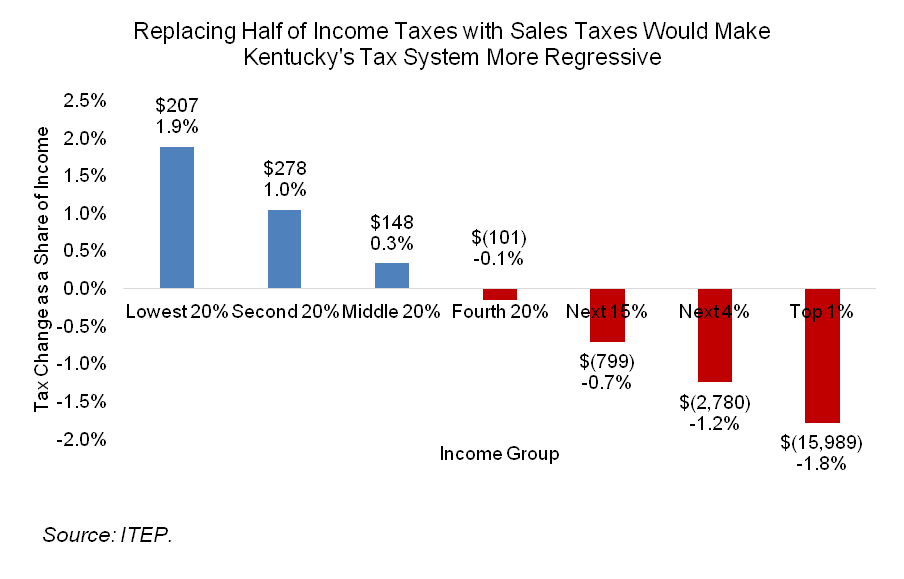

In the absence of detailed proposals to shift taxes like those illustrated above, some advocates of a consumption-based system use the fact that a larger share of Kentucky’s General Fund revenue comes from the individual income tax (42 percent) than the sales tax (33 percent) as a reason to claim a shift is needed. That is certainly a specious argument if the goal is to fund pension liabilities and invest in our other needs; stronger income tax growth has protected Kentucky from even deeper budget cuts than have already occurred over the last decade. And as in the examples above, a revenue shift is a tax shift from the wealthy to everyone else. For example, if half of Kentucky’s income tax revenue were replaced with sales tax revenue, families in the bottom 20 percent would pay about 2 percentage points more of their income in taxes, while the top 1 percent of Kentuckians would pay about 2 percentage points less, for a tax break at the top of about $16,000.

Governor Bevin has even expressed interest in eliminating the income tax, which if replaced initially with sales tax revenue would be a tax cut for the very wealthiest 1 percent of Kentuckians averaging more than $30,000 a year.

According to ITEP, replacing all of Kentucky’s income tax revenue with sales tax revenue would require an increase in our sales tax rate to 13.3 percent – more than double the current 6 percent rate and by far the highest state sales tax rate in the country (next highest is California at 7.5 percent). But since a shift would slow revenue growth, the initially revenue-neutral impact would become increasingly negative over time, leaving legislators to choose between raising the sales tax rate even higher, increasing other taxes and/or cutting funding for schools, child welfare and other investments. In states that have experimented with tax-shifting, income tax cuts have not paid for themselves, but have led to education funding cuts, credit rating downgrades, and the need to raise other revenue sources.

The bottom line is that weakening our income tax and relying more on sales tax is a regressive and revenue-slowing tax shift – not tax reform. Instead of undermining the income tax, we should be protecting and strengthening our overall tax system by cleaning up tax breaks for powerful interests. That’s the only way for Kentucky to sustainably meet obligations and invest in an educated workforce, healthy families and strong communities.