Far from collapsing, the health insurance exchanges set up by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are a way many Kentuckians are now able to buy health insurance. It will be important for the 81,155 Kentuckians who depend on that coverage for those in Washington to keep it stable rather than undermine it with administrative changes, threatened repeal of the ACA or even reckless public statements that cause insurance companies to question their participation.

Numbers from this year’s open enrollment show a functioning marketplace

Kentucky’s enrollment was lower this year than in past years, but several things contributed to the enrollment drop (including the switch from our state-based exchange Kynect to Healthcare.gov and the federal government pulling advertisements for healthcare.gov in the final weeks of open enrollment). And the drop is far from a so-called insurer “death spiral.” One indication of a death spiral would be an insurance pool with a disproportionately higher percentage of older enrollees. But data from healthcare.gov shows a fairly even mix:

- 34 percent were under 35 years old

- 34 percent were between 35 and 54

- 32 percent were 55 and older

This data set does not provide any information on the health of the people who purchased insurance through the marketplace. It does, however, offer information on what kinds of policies people purchased, which indicate what people thought they could afford and what level of care they thought they would need (the higher level the plan, the more expensive it is and the more it will cover).

- 843 people signed up for the lowest level of coverage, called “catastrophic” insurance.

- 17,974, or 22 percent signed up for bronze level insurance.

- 57,681 or 71 percent signed up for silver level insurance.

- 4,657, or 6 percent signed up for gold level insurance. No one purchased platinum level insurance in Kentucky.

Normally, people choose higher quality plans (such as gold or platinum) if a higher level of care is believed to be needed. But since the vast majority of people chose lower “metal” plans this means either they didn’t feel like they could afford plans with greater coverage, or they were healthy enough not to need them.

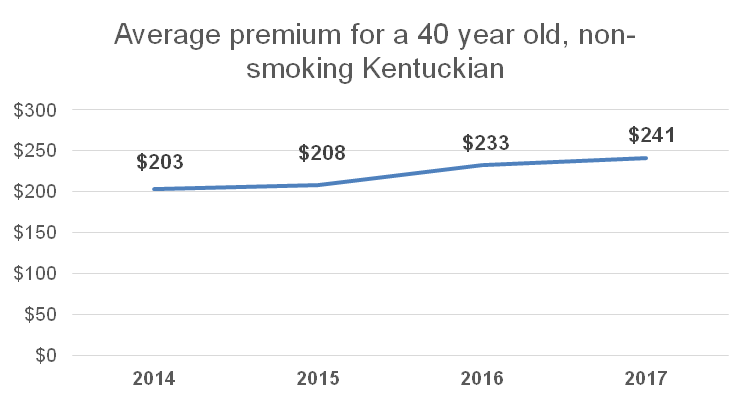

The other indication of an insurer death spiral is exponentially increasing premiums over a short period of time. But in Kentucky, while premiums have risen, they have generally tracked with pre-ACA premium increases and have not grown sharply enough to suggest a collapsing market.

Sources: The Urban Institute & KCEP analysis of Healthcare.gov 2017 marketplace rate data.

Further, the Congressional Budget Office and Standard & Poor’s, both said the individual insurance policy market is stable and the American Academy of Actuaries wrote a letter to Congressional leadership urging them not to destabilize the market by repealing the ACA without a “viable replacement.” These organizations made explicit what the data show: the marketplaces are not unraveling.

Most Kentuckians in the marketplace are protected from unnecessarily expensive coverage

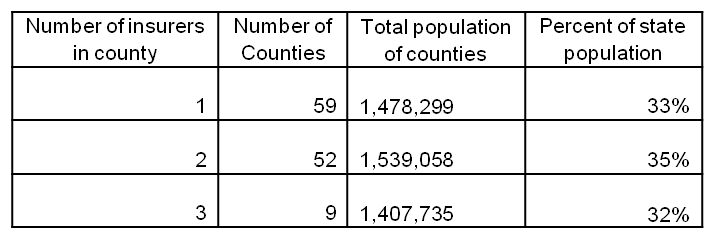

It is true that there were twice as many insurance companies participating in the marketplace in 2014 as there are today and that 59 of Kentucky’s 120 counties had only one insurance company (Anthem) offering plans this year.

While certainly not ideal, this is not as big of an issue as it seems. The portion of Kentucky’s population with only one insurer is 33 percent, with the remainder having 2 or 3 companies to choose from. Each of these insurers also offered multiple levels of coverage and some had multiple options within the same level of plan (HMO vs. PPO for example).

Source: KCEP analysis of 2017 Healthcare.gov data and 2015 Census Population Estimates.

Having only one insurer doesn’t mean there will be monopoly-driven, runaway premium hikes for two reasons. First, most customers get assistance paying for premiums, so for low-income Kentuckians especially, out of pocket costs for premiums are capped at a low level regardless of the amount of the premium. While insurance premiums vary based on numerous factors (county of residence, size of household, quality of insurance policy, insurance company, etc), the average premium in 2017 was $406 before subsidies—and actual costs were much lower:

- Four in five people who purchased insurance received financial help paying for their premiums.

- Those who got premium subsidies ended up paying an average of $144 per month.

- Half of the Kentuckians who purchased insurance through the marketplace got further help paying for out-of-pocket costs like deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance (this is called Cost Sharing Reductions or CSRs).

Secondly, under the Affordable Care Act insurance companies are only allowed to keep 15-20 percent of their revenue for things like profit and administration. If they end the year with any more premium-generated revenue than that, they have to offer rebates to their enrollees. In fact since 2014 Kentuckians have received $33 million in rebates. This cap keeps insurers from capitalizing on monopolies by running up their profit margins.

Congress played a role in causing the decrease in number of insurers in the marketplace — in particular decisions it made affecting health insurance cooperatives and a federally administered funding stream — called risk corridor payments — that was designed to help all insurance companies participating in the exchanges through the initial years. The ACA supported the creation of cooperatives as an additional health insurance alternative that would be non-profit and owned by the people who purchase insurance from them, ideally reducing cost since they would not be profit-seeking. In 2015 Congress changed the rules and only paid out 12.6 percent of risk corridor payments, causing Kentucky’s health insurance cooperative to go under because its growth strategy relied on those funds in its early stage.

Healthcare reforms should build on our successes, not undo them

While the marketplace is stable and fears about its imminent collapse are overblown, improvements can be made. Kentucky’s overall uninsured rate has dropped to only 6.5 percent thanks to the ACA, but the percentage jumps to 15.4 percent for people who earn too much to qualify for assistance with paying premiums and don’t get coverage through work according to 2015 Census data. There are ways we can and should assist the people who were left out. Some options that should be considered include:

- Increasing the income eligibility limit for people receiving help paying premiums from its current level of 400 percent of poverty to 500 percent or even higher.

- Allow people aged 55 to 64 to be able to “buy-in” to Medicare early.

- Introduce a “public option,” which is a government sponsored insurance program, into the exchanges.

- Bring back the risk corridor funding that help financially support new insurance programs like the co-ops while they were getting started.

- Offer a public re-insurance program for insurance companies that end up paying out more in claims than they bring in through premiums.

The real threat to the marketplaces is not looming collapse on their own, but that they will be deliberately destabilized over time through executive action or undermined by threatened repeal of the ACA.