The “Indiana model” for Medicaid expansion has recently been held up as a possible alternative for Kentucky, with supporters arguing that Medicaid recipients should have more “skin in the game” by paying premiums and co-pays for services. However, such an approach could prevent low-income people from getting the care they need — making health problems costlier down the road and creating barriers to sustaining the health coverage gains Kentucky has made in recent years.

Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion has been very successful. It has provided health coverage for more than 400,000 low-income Kentuckians and contributed to the state’s dramatic drop in uninsured rates, from 20.4 percent in 2013 to an estimated 9 percent in the first half of 2015, according to Gallup. Many covered by Medicaid are utilizing preventive care services, which are expected to improve future health outcomes. For instance, in 2014 90,000 Medicaid expansion members received cholesterol screening and 80,000 expansion members had preventive dental care. This impressive uptake in preventive care is expected to help with Medicaid costs in the future as improvements in health occur due to problems being caught and treated early.

Indiana expanded Medicaid through a federal waiver that allows it to implement the expansion differently than other states. For instance, unlike most other states, Indiana’s waiver requires enrollees to pay a monthly premium and some co-pays. The program, called the Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) 2.0, is unique to Indiana and has not been tried in other states. It builds on a waiver the state used to offer coverage to a small number of low-income residents prior to federal health reform.

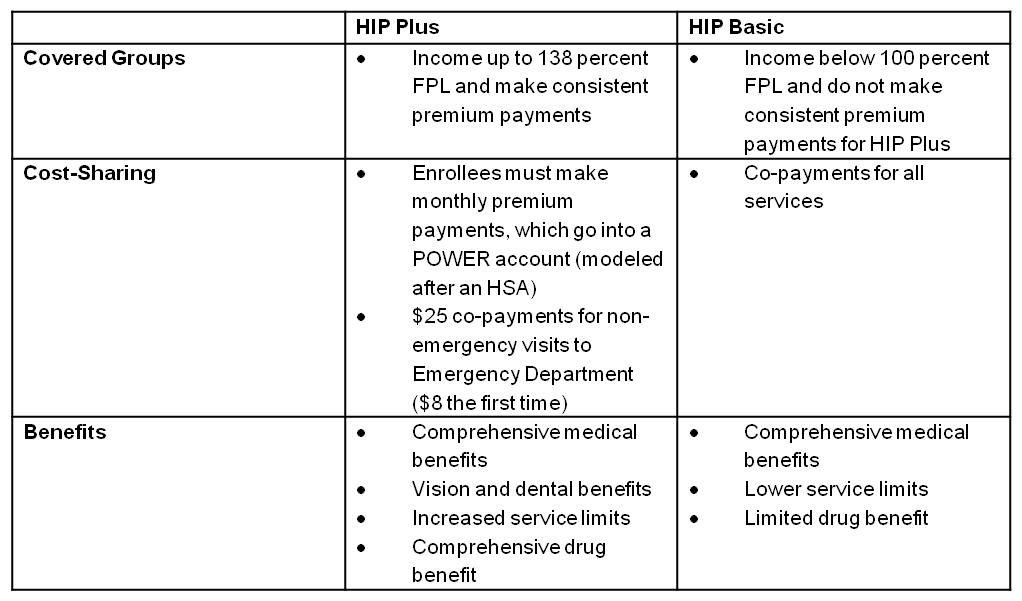

HIP 2.0 functions as two different programs for Medicaid-eligible adults who are not elderly or disabled: HIP Plus, a program with few co-pays and more comprehensive benefits but a monthly premium, and HIP Basic, a program for those with incomes below the poverty line who are unable to afford HIP Plus’s premium payments. HIP Basic requires co-payments and provides more limited coverage.

HIP Plan 2.0 comparison Source: Indiana Family & Social Services Administration, “Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0,” presentation to state budget committee, June 20, 2014.

Source: Indiana Family & Social Services Administration, “Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0,” presentation to state budget committee, June 20, 2014.

In order to enroll in the comprehensive coverage offered in HIP Plus, enrollees must pay a monthly premium ranging from $3 to $20 for those with incomes below the poverty line (below $11,670 a year in 2015 for an individual) and set at $25 for people with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of poverty (between $11,670 and $16,105 for an individual in 2015). This means parents in a family of four with incomes just above the poverty line, which is $23,850 for a family of four, would pay $50 a month ($25 for each adult) or $600 a year. Those with no income at all pay $1 a month for Medicaid coverage.

Unlike Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion, Indiana’s:

• Locks people out of coverage if they are unable to pay. Those with incomes at or below the poverty line are locked out of HIP Plus if they miss a payment and don’t make it up within 60 days. For the period they are locked out, they are automatically enrolled in HIP Basic, a program with co-payments and fewer benefits (i.e., no vision and dental coverage). If they do not pay the initial premium, they will also be enrolled in HIP Basic, but they must wait 60 days.

Those with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of poverty who miss a payment and don’t make it up within 60 days are also locked out of the program for six months, but they do not qualify for HIP Basic and lose health coverage entirely for that period of time.

HIP Plus members from both income categories may also be responsible for medical debts if they are dropped from the program for failing to make a premium payment.

• Does not provide retroactive health care coverage as traditional Medicaid does (for three months prior to application). Such coverage can prevent low-income persons with health problems from becoming buried in medical bills prior to enrollment in Medicaid. That component along with the potential loss of coverage mentioned previously threatens one of the most clearly measured benefits of expanding access to Medicaid: the reduction in catastrophic medical bills. This not only helps with medical bills for those who are uninsured — but has been beneficial for hospitals that have experienced significant drops in uncompensated care.

• Does not cover non-emergency transportation to doctor’s appointments, which is covered by traditional Medicaid. Despite having health coverage, transportation is a barrier for many low-income persons who need medical care — especially if public transportation is not available or if a provider is not located close by. In most states, transportation assistance is provided through the Medicaid program for little to no cost to recipients.

Perhaps most importantly, the added cost in the form of premiums and co-pays for very low-income Kentuckians is likely to inhibit access to health care that is the main goal of Medicaid expansion.

In Indiana, those unable to afford monthly premiums are likely not able to afford co-pays they would then have to pay at doctors’ visits. Some will respond by making fewer preventive care appointments and waiting longer to seek care for potentially serious conditions, leading to poorer health outcomes. The more limited coverage of those who can’t afford premiums includes the loss of vision and dental coverage, which means additional health problems can go untreated. Having to provide transportation for doctors’ appointments would also be a significant challenge for some.

According to an extensive body of research, premiums create a barrier for health coverage for many low-income individuals — especially those below the poverty line. For instance, Oregon received approval in 2003 to increase the premiums it charged participants in its Medicaid waiver program and also impose a six month lock-out period for non-payment of premiums; a study found that following these changes, enrollment in the program dropped by almost half. Similar effects occurred with programs in Utah, Washington and Wisconsin.

It is likely that imposing premiums on beneficiaries would lead to fewer low-income Kentuckians enrolling in health coverage at all. The HIP 2.0 model may be even more expensive for some than buying health insurance coverage with the help of tax credits through Kynect, the health insurance marketplace. Meanwhile, given the modest cost-sharing amounts involved, the administrative cost of collecting premiums and co-payments may end up approaching or exceeding the amount collected. Additionally, if drops in preventive care occurred the state would miss out on related health care cost savings due to unmanaged health conditions.

Through the Medicaid expansion and Kynect, Kentucky has made tremendous progress in reducing the number of uninsured and providing greater access to preventive care that can improve health outcomes down the road while providing economic benefits to the state. Before seriously considering an alternative model for Medicaid expansion, Kentucky should closely watch the impact in states like Indiana. Given Kentucky’s success so far, a new model would have a lot to prove.