The COVID-19 pandemic impacts all people but creates distinct challenges for the 422,000 Kentuckians working on the frontlines of the response, known as essential workers. Frontline industries – which require public interaction to help people meet basic needs and are too critical to be closed during the pandemic – include grocery stores and pharmacies, cleaning services, trucking and warehousing, public transportation, health care, and child care and social services.

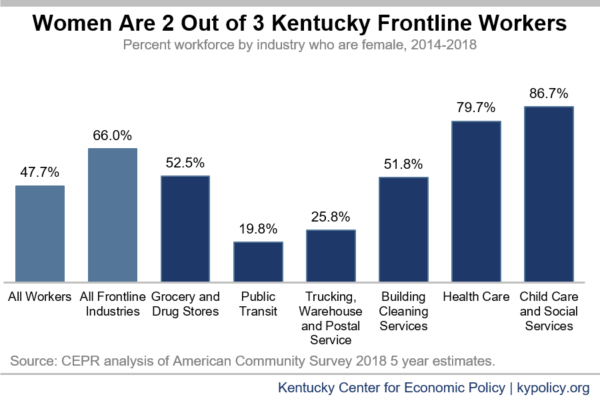

These positions have always been essential, yet many are underpaid and under-protected. A new analysis from the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) shows frontline Kentucky workers are more likely to be women, and black Kentuckians are overrepresented in some frontline industries. The policy response to COVID-19 will consequently shape how the pandemic affects long-standing gender, racial and economic disparities.

While some emergency protections are being enacted, more is needed to support the health and economic security of these workers both in the context of COVID-19 and beyond.

Women and black Kentuckians are overrepresented in frontline industries

In Kentucky, women make up 66% of frontline workers, compared to just 48% of all positions in the workforce. This includes 172,300 women in the health care industry (80% of health care employees). Women also make up 87% of the child care and social services sector, including social workers, child care workers, community housing advocates and emergency service workers. Similar to the share of all workers, 37% of Kentucky’s essential workers have a child in the home, and 13% have a person over age 65 in the home, meaning many are juggling paid work with unpaid caregiving under unprecedented conditions.

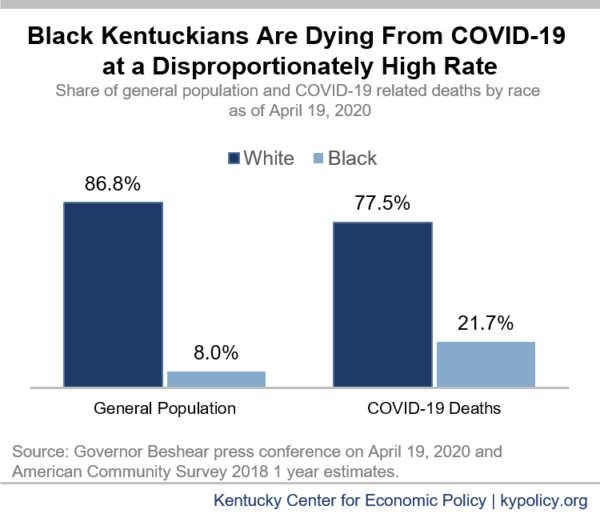

In some frontline industries, black workers are overrepresented. Though 8% of all Kentucky workers are black, 16% of cleaning service workers and 15% of child care and social service workers are black – two of the lowest paid industries on the frontlines. Hispanic and immigrant Kentuckians are also overrepresented in cleaning services, and that industry is among those least likely to have health insurance.

The disproportionate representation of Kentuckians of color in certain frontline industries contributes to racial inequities in health. Frontline workers are at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 due to exposure, and black Kentuckians are more likely to die from the disease due to numerous factors related to structural racism.

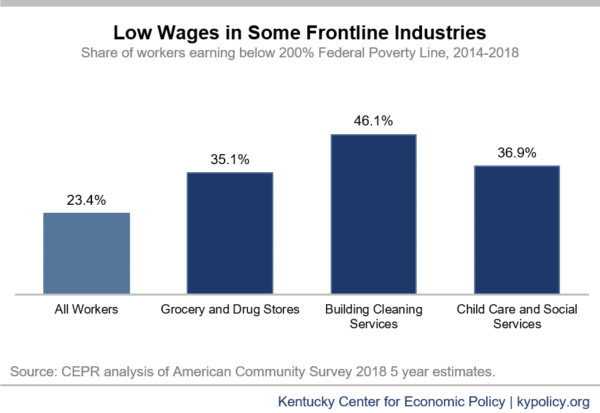

Many essential workers have wages too low to make ends meet

As the graph below shows, workers in some frontline industries struggle with very low incomes. Just over 8% of frontline workers overall make below the federal poverty line ($26,200 for a family of 4) and 23% make below twice the poverty line ($52,400 for a family of 4) – similar to the share of all workers making such low wages. But nearly half (46%) of Kentuckians working in cleaning services, 37% of workers in child care and social services and 35% of grocery store workers make at or below 200% of the federal poverty level.

Low incomes make it particularly difficult for workers in these historically undervalued positions to take off work to care for children out of school due to COVID-19, or to stay home if they are sick or dealing with underlying conditions that make exposure more dangerous for them.

Too many Kentucky essential workers lack health insurance

Low wages make it difficult to afford health insurance and are often accompanied by a lack of employer-sponsored health coverage, and that is true among certain frontline workers. According to CEPR, while just 8% of all Kentucky workers lack health insurance, 16% of workers in cleaning service positions and 11% of those in the trucking, warehouse and postal service industry do not have health insurance. Not only are frontline workers and their families at an increased risk of exposure to COVID-19 as a result of their work-related interactions with the public, but some also face a higher risk of financial crisis due to costly medical bills if they get sick.

Increased pay, benefits and access to health care would better support frontline workers

Several federal and state actions have been taken to support frontline workers. However, much more is needed in the context of COVID-19 and beyond.

Normally, low-wage workers like those in frontline industries have very limited access to paid sick days — only 3 out of 10 of the lowest paid workers. At the federal level, the Families First Act provides emergency paid sick leave and family and medical leave during this crisis. However, with only 2/3 of wages being paid by the federal government under emergency family and medical leave, low-wage frontline workers may not be able to afford taking off work to care for children out of school. And health care workers, emergency responders and people working in a business with over 500 employees are exempt from receiving leave. Also Kentucky lacks a paid sick leave law, and preempts local governments from creating them.

At the state level, emergency actions have been taken to make it easier for low-wage workers under 65 to apply for health insurance if they need it through simplified Medicaid applications. That coverage only lasts 90 days, however. Actions have also been taken to increase essential workers’ access to child care through limited approved centers opened just for their families. Additionally, workers’ compensation is being provided to essential workers exempt from emergency paid leave so that they can self-isolate or seek care due to occupational exposure to COVID-19.

Along with these protections, during the pandemic essential workers need to be compensated adequately through hazard pay, provided with free PPE and other worker safety protections and provided insurance that includes free coverage of COVID-19 treatment. These changes would help ensure their health and economic security, and mitigate the especially heavy strain of the pandemic on women and people of color.

The crisis makes more visible how critical these workers are to our economy and well-being at all times, and the longstanding importance of improving their job quality. That means a need for policy changes beyond this crisis like raising Kentucky’s minimum wage, addressing race and gender pay gaps, providing paid sick and family leave to all workers, and making health care and child care affordable.