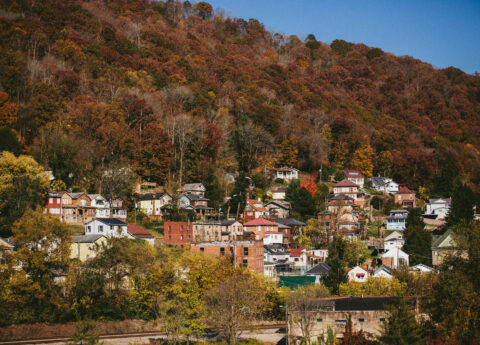

Fifty years ago, President Lyndon Johnson declared an “unconditional war on poverty” in his State of the Union Address. A few months later, he made a historic visit to Inez, Kentucky and the porch of unemployed sawmill operator Tom Fletcher to dramatize its need.

The anniversary of those events has sparked commentary about the effects of the anti-poverty policies and programs the War on Poverty launched.

As more than a dozen economists show in an important new book, Legacies of the War on Poverty, the era’s efforts made a real difference in alleviating the kind of grinding privation that was once common in many parts of the country. Poverty and economic hardship would be much worse today if it weren’t for the efforts begun during the War on Poverty, such as food stamps (now called SNAP), and continued in later decades, like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and child care subsidies.

In fact, using a comprehensive measure of poverty that takes into account non-cash benefits like food stamps and the EITC, the poverty rate fell strikingly—from 26 percent in 1967 to 16 percent in 2009—according to an analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

These gains came from a commitment to reducing poverty that was broad and robust. In his 1964 State of the Union address, Johnson declared that “no single weapon or strategy will suffice,” and in a few years federal spending on health, education, employment and training, housing and income supports more than tripled.

Those investments yielded substantial benefits for children, workers and families:

• Title 1 funding narrowed the wide gap in spending between rich and poor schools.

• College aid programs, including what became Pell Grants, increased access to higher education for low-income students.

• Head Start programs led to increased school completion rates for poor kids.

• Food stamp and nutrition programs alleviated severe hunger and malnutrition and improved child health and development.

• Expanded access to health care through Medicare, Medicaid and community health centers sharply reduced infant mortality and increased life expectancy.

One of the biggest successes was the rapid decline of senior poverty, due in large part to increases in Social Security benefits and access to universal health care coverage through Medicare. Senior poverty fell from 35 percent in 1959 to just 9 percent in 2010.

Another important but under-recognized contribution was the War on Poverty’s role—in combination with the civil rights legislation of the era—in promoting racial desegregation. New funding for schools, hospitals and housing was contingent on local governments and private groups ending segregation in facilities and addressing discrimination.

Despite these successes, some pundits and politicians have claimed that the War on Poverty was a failure. A more substantive critique is that the efforts didn’t go far enough to reach the goal of eliminating poverty.

One major factor is that the War on Poverty was launched while economic and wage growth in the United States were strong, and it was plausible to believe that a “rising tide would lift all boats.” However, the link between wage growth for low- and middle-income workers and broader economic growth was broken in the early 1970s. While workers’ wages have stagnated since then, incomes at the top have soared. And full employment—meaning a job for more or less everyone in search of work—has been rare and fleeting in the intervening years.

Also incomplete is the War on Poverty’s goal of greater democracy through “maximum feasible participation of the poor” in decision making. Some efforts to increase involvement of the poor on local boards and remove politics from programs were met with strong resistance from local power brokers, including in parts of Kentucky.

But rather than tarnish the rest of the War on Poverty’s record, these shortcomings point out the work still ahead of us. We should protect and build on the gains that were made these last fifty years, while doing more to address the gaps in economic justice and democracy that confront us in our time.