All Kentucky children deserve a high-quality education that equips them to live well and contribute fully to their community and the state’s economy. The most efficient and equitable way to invest state tax dollars to benefit all children is to adequately fund Kentucky’s public schools, as is required by the state constitution. Unfortunately, the state has deeply cut education funding over the past decade, leading to serious challenges for public schools and Kentucky communities, including a funding gap between poor and wealthy districts nearing levels declared unconstitutional 30 years ago in the Rose Decision.

House Bill 149 (HB 149) and its companion bill in the Senate (SB 25) would, if passed, severely strain the state’s ability to adequately fund public schools. It would do so by creating a new special interest tax break that would siphon a large and continuously expanding pot of monies from the state’s General Fund and give those resources to unaccountable private schools.

The tax break, at 95-97% of the amount contributed to the voucher program set up by the legislation, would be the most generous tax break in the state of Kentucky by far. It would divert scarce public dollars to privately controlled organizations that would then use them to pay for private school tuition and fees, uniforms, college test preparatory courses and a long list of other educational services. Though some public education expenditures are included, these funds would be more efficiently and equitably administered by Kentucky’s public schools instead of handing them to the unaccountable private intermediaries that HB 149 creates.

Direct public spending on private schools through vouchers is prohibited by Kentucky’s constitution. But many states have circumvented this prohibition to accomplish the same purpose by spending through the tax code, known as a neo-voucher program. HB 149 is a voucher at its core, using the tax code in a bureaucratic maze to reduce resources available for coordinated state investments in our public school districts and handing over control to private entities.

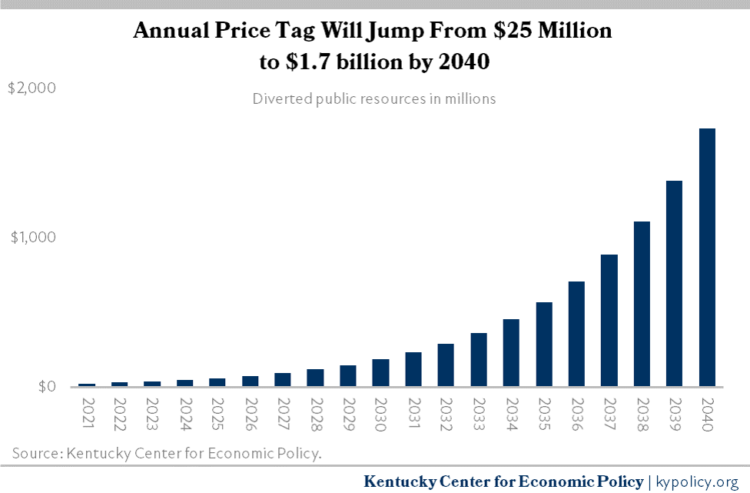

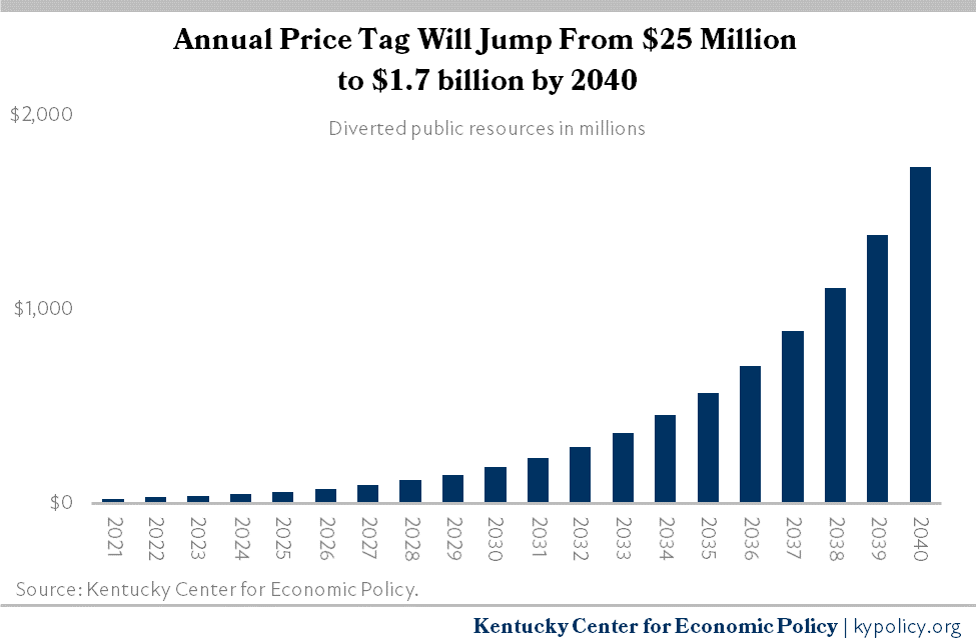

Tax break would grow astronomically over time, diverting more resources from P-12 classrooms

In the first year, the tax break created by HB 149 would cost Kentucky’s budget $25 million. Because of a growth provision — similar in design to this Florida program where annual costs in 2020 reached $874 million — by the third year, Kentucky’s program would cost more than was budgeted for education technology across the commonwealth this year. By 2031, when Kentucky kids who are in second grade this year graduate high school, the program would have already diverted over $1 billion away from the state budget — resources that would otherwise be available to invest in early childhood, preschool, K-12 classrooms, college affordability and other public priorities. By 2040, the cumulative cost will be $8.6 billion.

The large, growing costs of the program will be realized because of the generosity of the tax credit, with some donors actually making money off their donations, as described later. The graph below illustrates the large and growing amount of money that will no longer be available for appropriation by the General Assembly for public priorities if HB 149 is made law. The cost will continue to rise after 2040 because the program has no cap.

Unlike investments made through the appropriations process that are reconsidered every two years when the General Assembly enacts a budget, tax breaks like HB 149 are made permanent in the statutes, indefinitely and automatically draining resources from public priorities to special interests. Tax breaks by design receive first priority before a single dollar is appropriated for any other needs. The history of tax breaks shows that when action is needed to balance a revenue shortfall, the General Assembly is far more likely to cut budgeted services like childcare, school transportation, need-based college scholarships and public health, for instance, instead of reducing tax breaks.

And while proponents have falsely claimed that the overall cost of this tax break is reduced when participating students leave public schools, relieving local school districts of the cost of educating those students, research shows otherwise. Programs like the one established by HB 149 end up primarily serving the most advantaged families eligible, whose students are often already attending and paying for private schools — just with the state footing the bill. Even when students do leave public schools, districts are not able to reduce costs proportionally. As Kentucky educators and administrators testified in committee in 2019, when enrollment declines, schools’ fixed and stranded costs remain the same.

The reduction of General Fund resources caused by HB 149 would come at a critical time for Kentucky’s P-12 classrooms, which have not been spared the effects of over a decade of deep budget cuts since the Great Recession. Per-pupil SEEK funding (Support Education Excellence in Kentucky) is 16% below 2008 levels, Extended School Services have been cut nearly 40% and Family Resource and Youth Service Center funding is down nearly 15%. Because of the decline in state resources devoted to education, and a growing reliance on local dollars, the funding gap between students in wealthy and poor districts continues to climb — to $2,840 in 2019, the last year for which data are available. Inadequate funding has led to unequal opportunities for children in wealthy and poor districts, and the challenges caused by these inequities would be worsened by this new, costly tax break.

Voucher would worsen inequities

Proponents suggest programs like that proposed by HB 149 are a way to provide school choice to families who would otherwise not be able to afford it. But HB 149 will primarily benefit better-off families that in many cases already pay for and attend private schools because of the way its eligibility rules are designed.

- Income eligibility for the program is up to 370% of the federal poverty line (FPL) based on family size.

- 70% of Kentucky children would be eligible based on this threshold. For instance, a student from a family of 4 with $96,940 in annual household income would be eligible.

- Students only become ineligible once their household income surpasses 463% of poverty — up to $121,175 for a household of 4. The cutoff is so generous that 79% of Kentucky children would be eligible to remain in the program despite household income growth.

In effect, only the top 21% of the wealthiest households in Kentucky would be ineligible to participate. This means that many families who are already paying for and can afford private school, costs related to homeschooling or other alternatives will be eligible for the state to pick up these costs. While the bill allots a majority of funds for first-time applicants to students below 185% of poverty, priority for all available funds after the first year goes to those who are already in the program. The creates a scenario where, over time, a larger share of the total resources will likely go to wealthier families whose income can grow up to 463% of poverty before eligibility for the program is cut off.

As previously stated, research shows that programs like these end up serving the most advantaged families eligible for them. Applying for funding through one of the private organizations the legislation creates, and identifying and accessing available educational service providers, will be easiest for well-resourced families in communities with ample educational options. Accessing the program will be more difficult for low-income working parents and those without reliable internet, cell phone service, transportation and access to educational alternatives. Few such educational alternatives even exist in Kentucky’s rural counties. Furthermore, poorer rural counties benefit significantly from state public school funding through the SEEK formula that would be threatened by diverted tax dollars.

Crucially, under HB 149, public resources would be diverted to private settings where students may be discriminated against based on the organization’s religious or other creed, practices, admissions policy or curriculum. The bill’s entire Section 11 reasserts the autonomy and independence of education service providers from state and local oversight and authority. There is no language in the bill to protect students from discrimination based on gender identity, sexual orientation, being an English language learner, disability status and religion, for instance, which are all well-documented problems with voucher programs. In fact, vouchers arose in response to Brown v. Board of Education to allow white parents to send their children to segregated private schools with the support of public subsidies. While state law protecting public school students from discrimination does not mean that it never happens, public school families also have more avenues for recourse than private school families when discrimination does occur. HB 149 would also fail to protect students in private school settings as understanding of and commitment to equity evolves. For instance, if Kentucky public schools are eventually required by state law to abandon racially discriminatory dress code policies, such protections and their recourse would not extend to private school settings — even as public resources would still flow from public to private schools.

Research suggests that contemporary voucher programs can worsen racial and socioeconomic stratification, as has been shown in Indiana. Kentucky already has a proven way to reduce disparities: systematically investing more in low-income districts, as has been and would be done by increasing the state’s contribution to SEEK and through programs providing special support for disadvantaged students. Such investment would increase resources for students in these districts and improve adequacy overall, helping to close “achievement gaps.” Funds diverted to private entities and individual families would not have the same level of oversight, nor be held to the same requirement of equity.

Program allows wealthy “donors” and private special interests to profit and direct the use of public resources

For donors of cash and marketable securities to the voucher program, HB 149 would carve out a large income tax break against individual, limited liability and corporate taxes. At 95 cents for every dollar of donations up to $1 million — increasing to 97 cents for multi-year donations — this incredibly rich tax break is 19 times bigger than the state’s charitable deduction for other kinds of giving to nonprofits such as to places of worship, veterans associations, animal shelters and food banks — and which nonprofit private schools already benefit from. It would be the most generous tax credit offered in Kentucky. A tax credit of this size — nearly a full repayment to the donor — is effectively the same thing as allowing private individuals and corporations to direct state tax dollars to their preferred purposes.

By stacking federal and state charitable deductions on top of the state tax credit, donors could recoup between 97% and 100% of their donation. And, if donors give securities, recouping their full, current market value plus avoiding capital gains taxes on appreciated value, they will actually make money. In other words, stock market investors would profit off of a scheme to divert public resources to private entities. Tax breaks like these cause inequality to grow between the wealthy special interests that gain from them, and the low-income families whose taxes go up when states like Kentucky increase regressive consumption taxes to pay for income tax breaks.

Also benefitting would be new privately controlled grant-making organizations created under HB 149. The legislation provides that the new organizations created to provide education accounts “shall implement a commercially viable, cost-effective and parent-friendly system for payment of services…to education service providers” but includes few standards to ensure that the system meets these requirements. The only language related to promoting “commercial viability” and “cost-effectiveness” in the bill allows the organizations to reserve up to 10% of funding for administrative expenses and to contract with “private financial management firms or other organizations” for developing the payment system, maintaining records and processing transactions. In other words, 10% of diverted resources — $170 million in 2040, for instance — can be spent on intermediaries. The bill also includes language that allows an ever-growing carryforward by the grant-making organizations, but is unclear how those carryforward funds must be used or accounted for. The bottom line is that the program would use scarce public dollars for wasteful administrative expenses at unaccountable private organizations.

Kentucky doesn’t need a scheme that 1) siphons off a large and growing pot of resources that would otherwise go to P-12 schools and other public priorities; 2) widens inequities and subsidizes discriminatory practices; and 3) allows unaccountable private organizations and wealthy individuals to benefit from and control public dollars. What Kentucky’s students need is a recommitment to adequate, equitable public school funding, and the kind of student-focused innovations that are possible when schools are not facing ever-scarcer resources from a tax code full of ever-growing breaks.