Click here to read a PDF copy of the full report.

Ten years ago, the Great Recession was battering Kentucky’s economy and that of every other state in America. Throughout the course of 2008, Kentucky lost an astounding 74,000 jobs and would continue to shed employment until February 2010, when we finally hit rock bottom with a total of 119,000 jobs lost. All was not well with the economy before the downturn hit, but the Great Recession tore a deep hole in the fabric of economic well-being across the commonwealth.

Since 2010, we have been living through what is now one of the longest economic recoveries on record. But the recovery has been slow and uneven, and despite the headlines about our now-low unemployment rate, the recovery is not complete. The state still lacks an adequate number of jobs, with certain regions and populations especially lacking in job opportunities. Too many of the jobs we have are of low quality, and much-needed wage growth is still largely missing in Kentucky.

That follows several decades where the wages of low- and middle-income earners have been stagnant or even declining in inflation-adjusted dollars, while incomes at the top have soared. And it is on top of long-standing inequities that continue to afflict our communities today. Barriers hold back progress for people of color, women and those in distressed rural communities among others.

In this report, we provide a snapshot of the economy today by looking at the conditions facing Kentucky workers. What matters for them is not how much wealth is being created or how well the stock market is performing. Front of mind for workers is the availability of quality jobs in their community. On that metric, Kentucky falls short.

To make improvement, we need federal and state policies aimed at creating more good quality jobs and fostering a higher standard of living. That will require investments in public goods and new rules for the economy aimed at increasing equity. Instead, policies enacted in the last few years — from tax shifts to deregulation aimed at ending worker protections and attacks on the safety net — just worsen inequality by redistributing income away from workers and communities to large corporations and wealthy individuals.

Kentucky workers need more from the economy than they are getting out of it today. Fixing that problem should be at the top of state lawmakers’ priorities.

Jobs

Kentucky has experienced regular job growth since hitting the trough of the Great Recession in 2010. However, we have not yet fully recovered from the job losses we experienced. One reason is the pace of job growth has been fairly slow, and that pace has weakened further in the last few years compared to earlier in the recovery. Whereas the state averaged 2,561 net new jobs a month in 2014 and 2015 according to Current Employment Statistics data, since the beginning of 2016 job growth has averaged only 1,073 net new jobs a month.

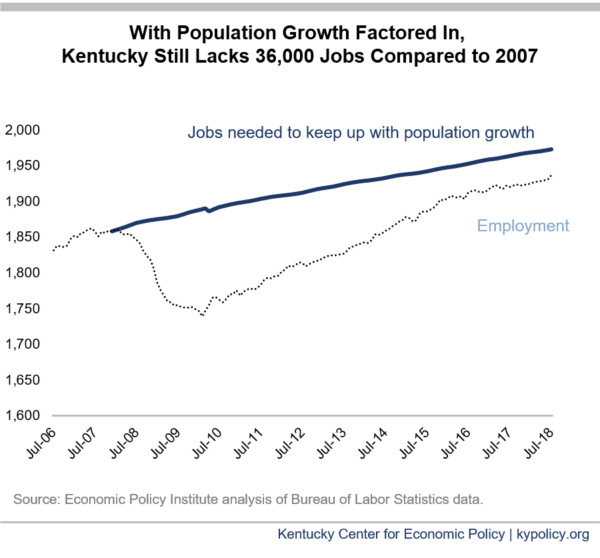

Slow job growth means the state has not returned to pre-recession employment levels. Once growth in the population since the recession is taken into account, we are still about 36,000 jobs shy of reaching the employment level we had in December 2007.

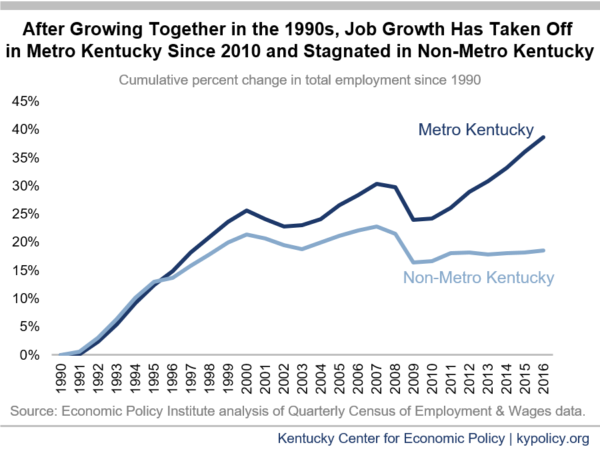

The gap in job availability varies across Kentucky, especially between metro and rural communities. Using Office of Management and Budget definitions, 58 percent of Kentucky’s population lives in metro areas while 42 percent lives in non-metro areas. Employment in metro and non-metro Kentucky largely grew together in the 1990s and followed similar patterns of growth and contraction through the recession of the early 2000s and the Great Recession. However, growth patterns diverged markedly during the recovery that started in 2010. Whereas metro Kentucky has seen strong job growth this decade, non-metro Kentucky has experienced essentially no net job growth. What gains have happened in an improving economy for rural Kentucky have been offset by job losses in declining industries.

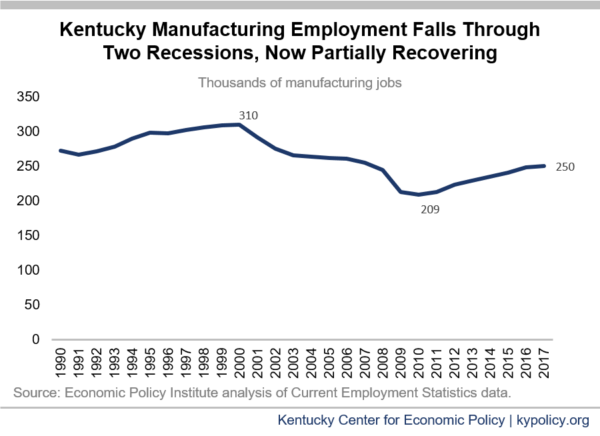

Changes in the composition of industry employment play an important role in how the recovery has unfolded. Overall, Kentucky’s industry makeup reflects a service-based economy with the largest employment in the sectors of 1) trade, transportation and utilities, 2) government and 3) educational and health services. Combined, these three categories are more than half of all Kentucky jobs. Manufacturing employment fell heavily in the 2000s due in part to two recessions and the growing U.S. trade deficit with countries like China. It has since made a partial recovery. The state peaked at 310,000 manufacturing jobs in 2000, but then proceeded to lose 101,000 or one-third of its factory jobs over the next 10 years. Since 2010, the state has gained back 41,000 of those manufacturing jobs.

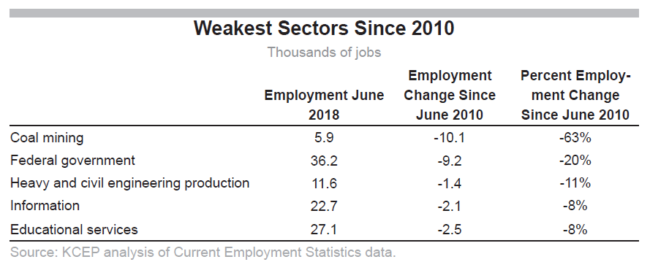

Since 2010, Kentucky has seen especially big declines in coal employment and in public sector jobs. Governmental employment has declined due to budget cuts at the federal and state level, impacting jobs ranging from higher education to highway construction. As a whole, Kentucky has shed a net 10,100 coal jobs and 8,600 governmental jobs since 2010.

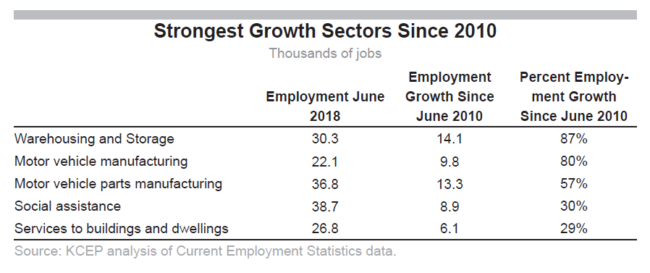

Employment increases, in contrast, have been strongest in the distribution sector, specifically warehousing and storage, where Kentucky’s central location in the U.S. plays a key role. Employment growth in motor vehicle and parts manufacturing has been strong as the auto industry recovers from its steep fall in the recession. The aging of the population is leading to greater employment in the social assistance sector, especially home care aides. Also growing faster than the state average are jobs in ambulatory health care (doctors’ offices) fueled by Kentucky’s expansion of health coverage; employment services (better known as temporary agencies), which companies increasingly rely on for outsourced low-wage labor; certain types of private construction and services to buildings and dwellings like landscaping; and restaurants.

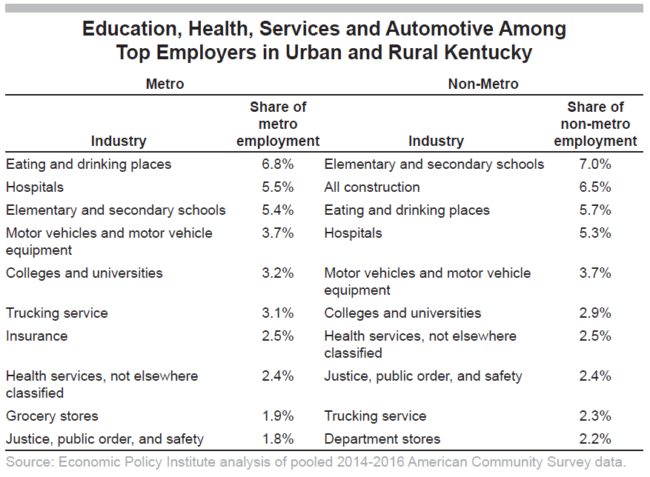

The different industry composition of non-metro parts of the state compared to metro Kentucky helps explain some of the divergence in employment growth between cities and the countryside. Overall, metro Kentucky has a disproportionately large share of the state’s entertainment and recreation, finance/insurance/real estate, and wholesale trade employment. Those industries and others that tend to be based in metro areas have seen stronger growth than industries non-metro areas rely on more heavily — mining, governmental employment, construction, elementary and secondary schools, and agriculture. The top overall employers in metro and non-metro Kentucky are listed in the table below.

Public investment plays a significant and direct role in a number of the major employers in both cities and rural areas — such as through funding public schools and universities, making payments to hospitals and providing public safety.

Labor Force

Much has been made of the fact that Kentucky’s unemployment rate, at 4.3 percent in July 2018, is at a level not seen since the year 2000 (and before that, at any time since the Bureau of Labor Statistics started providing state data in 1976). The decline in the unemployment rate from its peak of 10.7 percent in 2009 is good news. But the economy fell into a deep hole back then, and a close look at other labor force statistics suggests we have not yet fully recovered.

Perhaps one of the best labor force measures is the employment to population ratio (EPOP), which simply looks at the share of people who have a job. EPOP provides a broader picture than the unemployment rate, which only counts people as unemployed who have looked for work in the last four weeks. In an extended weak economy like the U.S. has experienced, EPOP importantly takes into account so-called discouraged workers — or people who are not currently searching for employment, but most all of whom have been employed at some time in the past.

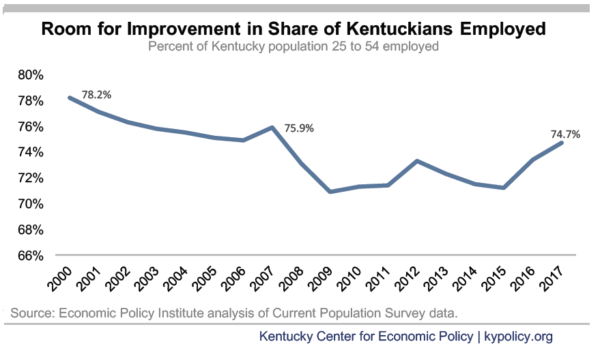

An important quirk in labor force statistics in recent years is the effect of the large baby boomer population. As baby boomers age into retirement, a bigger share of the total population will not be employed compared to the past. Therefore, a clearer way to examine changes in the EPOP over time is to focus on prime-age workers, or those between the ages of 25 and 54.

The EPOP of prime-age Kentuckians – 74.7 percent in 2017 – has increased since the recession but is still below where it was before the recession hit. And it is substantially below where it was in the stronger economy of 2000, when it reached 78.2 percent. For Kentucky to return to that mark today, approximately 60,000 more prime-age people would need to be employed. That is a large gap — especially considering, as mentioned earlier, the state often averages less than 2,000 net new jobs a month. The prime-age EPOP paints a less rosy picture of the job market than the unemployment rate alone.

Other labor force statistics also suggest slack remains in labor markets — meaning there is still a surplus of workers relative to the number of jobs that are available. For example, the share of part-time workers working part-time for economic reasons — also called the rate of involuntarily part-time because they would rather be employed full time — is still elevated in Kentucky at 13.5 percent compared to 9.2 percent in 2000.

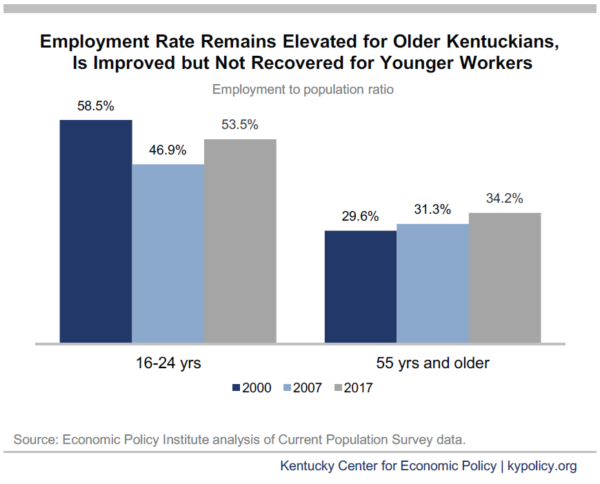

Among older Kentuckians, more are working than in the past, which affects the number of jobs available for younger workers. The EPOP for workers ages 55 and over remains elevated at 34.2 percent, significantly higher than it was in 2000 when only 29.6 percent of older Kentucky workers were employed. In contrast, younger workers ages 16-24 are less likely to be employed now than in 2000, at 53.5 percent compared to 58.5 percent. The decline of pensions and lack of retirement savings likely plays a role in older workers staying in the labor market longer.

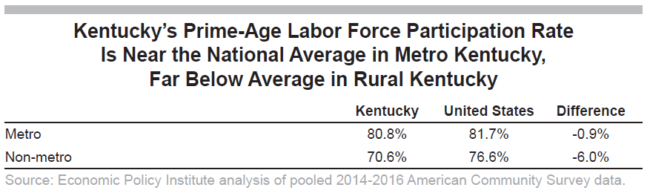

There is much conversation about how Kentucky’s labor force participation rate (the share of the population working or looking for work) is among the lowest of any state. Often this narrative blames workers for this fact, ignoring how the availability of jobs plays a major role. Rarely mentioned is that Kentucky’s overall labor force participation rate is pulled down by the economic conditions in rural Kentucky, where jobs are scarce. The state’s labor force participation rate for the working age population in metro Kentucky is nearly at the national metro average, but the rate in non-metro Kentucky is far below the national non-metro average. The decline of employment in sectors like coal, certain manufacturing industries and agriculture play a big role in the scarcity of jobs in rural Kentucky communities. In addition, the fact that Kentucky is a more rural state than the U.S. as a whole (58 percent metro in the commonwealth compared to 86 percent metro for the U.S.) contributes significantly to why Kentucky ranks so low in state-wide labor force participation.

The labor force challenges Kentuckians face depend on where one lives and also one’s gender and race. When it comes to gender, a combination of persistent discrimination, societal expectations, lack of policies supporting female workers and a changing mix of jobs in the economy affect male and female participation in the workforce. A higher share of men than women are employed, but men have a higher unemployment rate than women — meaning there is a greater share of men who are jobless and looking for work. Women are more likely than men to work part time, but male part-time workers are likelier to be doing so involuntarily. Both male and female labor force participation rates have risen the last two years in the expansion, after decades in which the male rate was declining and the female rate was stagnant.

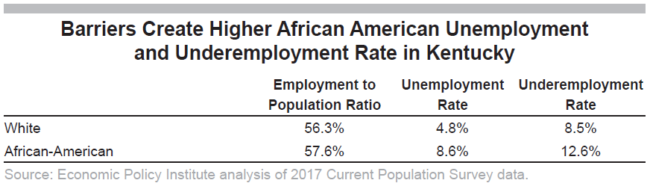

In terms of race, discrimination and a variety of systemic barriers that limit opportunities for people of color result in a higher African American unemployment rate than the white rate, at 8.6 percent compared to 4.8 percent for whites. One change in recent years is that the labor force participation rate used to be higher for whites than it was for blacks in Kentucky, but that relationship has reversed such that the rate for African Americans is now higher. One contributor may be that white Kentuckians are more likely to live in rural areas where proximity to jobs is a challenge (81 percent of workers of color live in metro Kentucky). Also, the labor force participation rate only counts the share of the non-institutional population in the labor force — meaning it excludes those in jail or prison. A variety of discriminatory criminal justice system practices have resulted in African Americans being imprisoned at rates disproportionately higher than whites in Kentucky. State-wide labor force data for other racial groups are more difficult to analyze due to small sample sizes.

Education is often held up as a strategy to improve employment outcomes. There is a sharp difference between the EPOP of Kentuckians with less than a high school degree (28.6 percent) and those with a bachelor’s degrees or more (76.5 percent). However, across all education groups, EPOPs remain depressed compared to where they were prior to the recession and in the stronger economy of 2000. In other words, even those with more education are less likely to be employed than they were in those earlier, economically stronger periods.

Wages

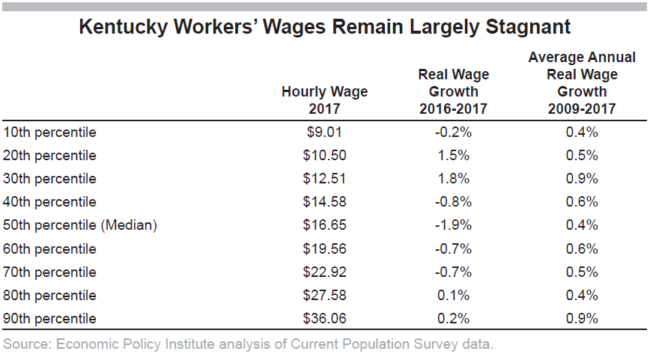

Despite an ongoing economic expansion, wages for Kentucky workers continue to stagnate. Real wage growth was non-existent for many Kentucky workers in 2017 across the income spectrum. In the years since the economic recovery began in 2010, average annual real wage growth has been barely noticeable.

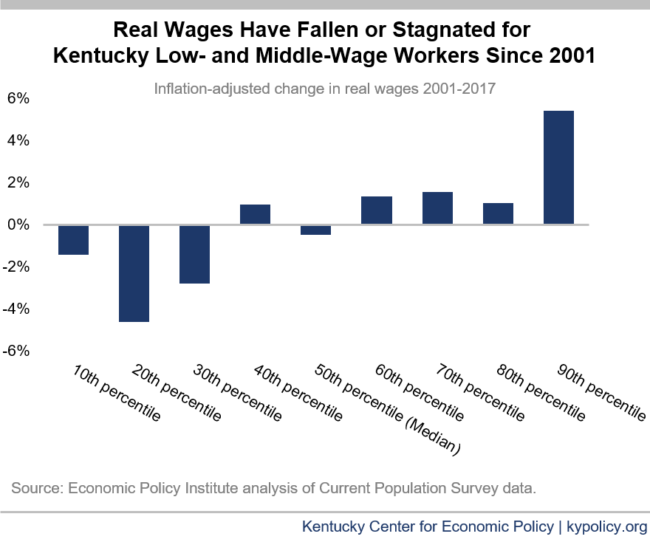

Stagnant wages are not a new phenomenon. Real wages have been flat or declining for Kentucky workers going back to 2001, even while workers at the top have seen increases. Real wages for Kentucky workers at the 10th percentile were 3 percent lower in 2017 than they were in 1979. At the median, wages were only 4 percent higher than nearly 40 years ago. In contrast, better-off workers at the 90th percentile have seen a 17 percent increase in real wages over that time.

Poor wage growth for workers on the bottom half of the distribution has occurred even as Kentucky workers’ productivity has grown. Economic Policy Institute analysis shows worker productivity in Kentucky — which refers to the total amount of output or income produced per hour of work — has increased 3.5 times more than median compensation for workers since 1979. A disproportionate share of the gains from economic growth are going to owners in the form of capital income and to managers’ salaries as opposed to workers in the form of wages.

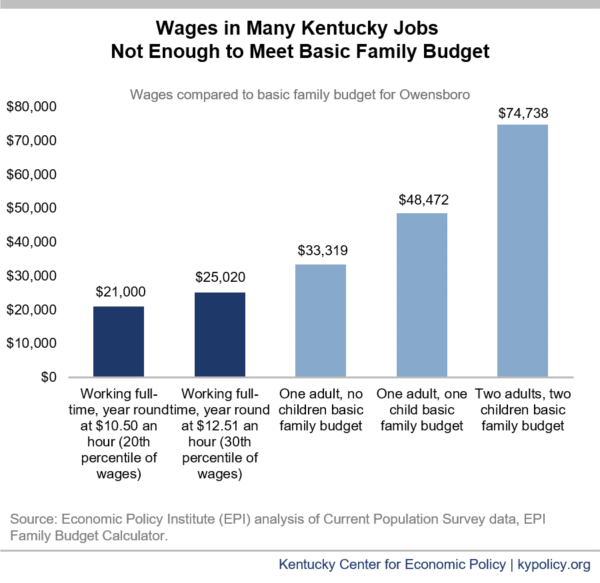

Wages are not only stagnant and failing to keep up with productivity, they are also in many cases inadequate to meet basic needs. Thirty percent of Kentucky workers make less than $12.51 an hour — a wage far below the amount needed to meet a family’s basic needs. Essential income support programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid help eligible low-wage workers better make ends meet, but in themselves are not enough to close the gaps in basic family budgets (calculated by the Economic Policy Institute as the amount needed to attain a modest yet adequate standard of living), much less allow families to save for college, retirement and other important needs.

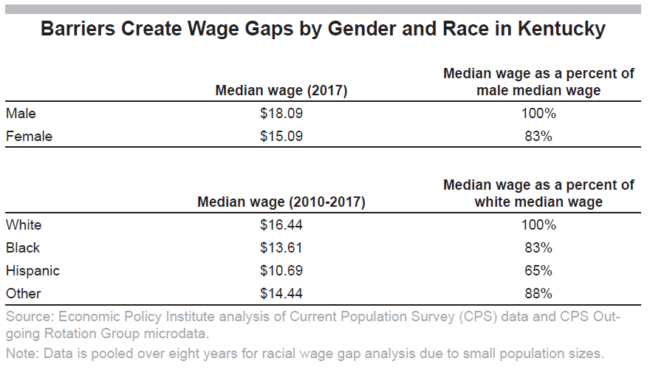

Kentucky also continues to experience significant wage gaps by demographic group driven by systemic barriers facing women and people of color. At the median, women in Kentucky make only 83 percent of what men do. Though that gap has been closing in recent years, it is partially because of stagnation in male wages. Black workers in Kentucky make only 83 percent of the median wages of white workers, and Hispanic workers make 65 percent.

The relative strength of Kentucky’s urban and rural economies also shows up in wages. Whereas the median wage in metro Kentucky is $19.49 an hour, it is only $17.05 an hour in non-metro Kentucky. A big pay penalty exists for those living in non-metro areas who have more education. Whereas Kentuckians with a high school degree or less make only 6 percent less in non-metro areas than they do in metro areas, those with a bachelor’s degree make 13 percent less and those with an advanced degree make 15 percent less.

Nevertheless, it is widely understood that those with greater levels of education tend to make higher wages overall. The median wage for Kentuckians with a bachelor’s degree or higher is $25.05 an hour, while the median is only $14.77 an hour for those with only a high school degree. However, having more education has not protected Kentuckians from the consequences of a weak economy for workers in recent decades. Real wages for workers with a bachelor’s degree or some college have been stagnant in Kentucky since 2001, just as they have for those with only a high school education. This data refutes the idea (based on anecdotal claims) that Kentucky is experiencing a widespread skills shortage, which would be indicated by wage growth for those with more education as employers pay more to obtain the skills they need. Instead, we see evidence of a labor market where workers of all education levels have little ability to bargain for better wages.

One way Kentucky workers traditionally have had bargaining power — even those with less formal education — has been through union status. In 2017, the median wage for Kentucky union workers was $20.19 an hour, or 27 percent higher than the median wage of non-union workers at $15.94 an hour. Kentucky’s recent passage of a so-called “Right to Work” law will weaken unions and the ability of all workers to bargain for better wages.

Policy Implications

After eight years of one of the longest economic recoveries on record, some observers are too eager to declare that the economy is vibrant. Kentuckians need a clear-eyed view of the real economic conditions — and whether the gains of growth are trickling down to typical workers and their families. Improvement has been present since 2010 in several ways, but major gaps, inequities and inadequacies persist. Policymakers must give greater attention to building an economy that creates good jobs for all Kentuckians.

An agenda to do so would include job creation policies to fill the substantial remaining holes in the fabric of actual employment opportunities across the commonwealth. We also need policies that improve job quality, raise real wages and support workers’ basic needs — and not those that erect new barriers. Specific recommendations include the following:

Push for a Full Employment Economy

The federal government has a crucial role to play in continuing to improve the jobs picture and ensure distressed places with few jobs have extra attention and support. Of critical importance in the near future is for the Federal Reserve to avoid raising interest rates to the point of choking off the recovery before full employment is reached. There is evidence slack still remains in the labor market, with inflation below targets and wage growth inadequate.

Congress also has a role to play in spurring a full-employment economy. There is a need for greater nationwide investment in infrastructure, which will both create jobs and improve the productive capacity necessary for future growth. Expanded investment in public service employment aimed at higher-paying jobs in areas ranging from child care to elder care would create quality opportunities in roles crucial to young people’s development and senior well-being.

The nation also needs to invest in regional strategies that target areas of the country still lacking adequate jobs, including central Appalachia and other parts of rural Kentucky. There is an emerging and promising discussion about the idea of a national job guarantee, where the federal government would step in to create public employment in places and times where the market falls short. Kentucky benefitted greatly from jobs created by the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps in the New Deal era, and there is much valuable work to be done today in areas like reforestation and land reclamation, parks revitalization, the arts, community development and more.

Raise Wages and Close Inequities

We also need state and federal policies that directly take on the problem of stagnant wages and address inequities based on race and gender. That includes a much-needed increase in the minimum wage, access to paid leave, an expanded EITC and pay equity laws. We must do more to remove barriers to employment many face, including by reforming the criminal justice system to reduce the number of Kentuckians with felony records. For more ways state policy can improve job quality and economic security for Kentuckians, see the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy’s recent report “An Economic Agenda for a Thriving Commonwealth.”

Finally, an agenda to lessen inequities must include abandoning impediments that make it harder for workers to succeed. Barriers to Medicaid and SNAP being proposed and implemented by the current administration will result in lost coverage and additional hardship without improving employment outcomes. Tax policies that cut taxes for the wealthy and corporations while shifting responsibility over to middle- and low-income Kentuckians will make it harder to fund the public investments crucial for worker advancement.

Improvement is normal in a recovering economy, but does not in itself equal success. By directly tackling the problems of inadequate jobs, stagnant wages and barriers to economic security, we can enhance the lives of workers directly. And by making things better for workers, we will build a Kentucky economy that works for everyone.