More than 800,000 Kentuckians are lifted out of poverty each year by safety net programs including Social Security, SNAP (formerly food stamps) and low-income tax credits for working families according to recent research from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). Of those 809,000, nearly one in four are children.

It’s a larger impact than was previously thought. New data from the Urban Institute takes underreporting of certain benefits into account to show just how many people the safety net serves (underreporting occurs when, for instance, someone forgets or is embarrassed to admit they’ve received benefits).

CBPP’s report combines that data with a way of gauging poverty called the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) which reflects not just wages and salaries, but also the resources people receive from SNAP, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and other programs, taxes and additional adjustments. Using SPM generates a clearer picture of the resources families have to meet their needs: food stamps to help put groceries on the table, housing assistance and working family tax credits to further supplement income.

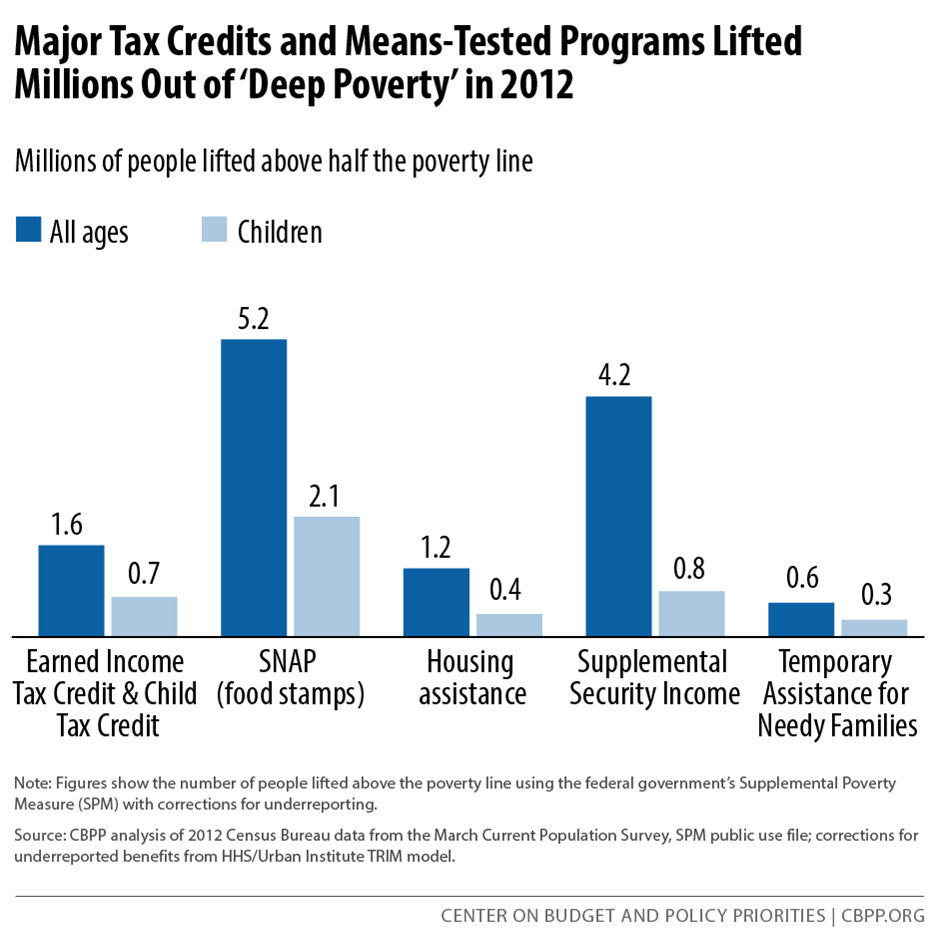

The report finds that safety net programs are an extremely effective means of fighting poverty. In Kentucky, data from 2009-2012 shows that:

- They cut the state poverty rate by almost two-thirds, from 30 percent to 11.2 percent.

- Safety net programs reduced the share of Kentuckians living below 50 percent of the poverty line — the threshold for deep poverty — from 20.7 percent (one in five) to 3.3 percent (one in 30).

- The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) alone lifted 164,000 Kentuckians out of poverty on average each year.

- Even without accounting for underreporting, the Earned Income Tax and Child Tax Credits (EITC and CTC) for working families lifted an average of 161,000 Kentuckians, 90,000 of whom were children, out of poverty each year from 2011 and 2013.

Alleviating poverty for families and individuals today is a meaningful outcome in and of itself, but research also shows that making these investments pays off down the road. For instance, children under six in households that see an additional $3,000 in income per year work more and make more money when they become adults.

The bad news is that improvements to the safety net made during the Great Recession — in particular to unemployment benefits, SNAP, the EITC and CTC — have begun to expire. These temporary boosts have helped many Americans across the income spectrum during hard economic times, but they have also alleviated a decade-long trend from 1995 to 2005 in which the safety net actually became less effective at protecting Americans from deep poverty, especially children in single parent families. Nationwide, the share of children living in deep poverty rose from 2.1 percent in 1995 to 3.0 percent in 2005. In 2005, safety net programs lifted about eight out of ten children living below half the poverty line above that threshold, compared to nine out of ten in 2012.

The reason for the pre-recession downward trend is that while welfare reform in 1996 put an important emphasis on supports for working poor families such as the EITC, assistance for deeply poor Americans through TANF was weakened.

Unfortunately, instead of strengthening investments in a brighter future for all vulnerable children, the Congressional budget resolution for 2016 would further cut safety net programs, putting more low- and moderate-income Americans at risk of falling into poverty, and others of falling deeper.