This November, Kentuckians will vote on an amendment to the state constitution that would permit the General Assembly to spend public money on private schools. 1 This report aims to examine what policies will likely follow if Amendment 2 is approved, and how they will impact education in the commonwealth.

The Kentucky General Assembly enacted a private school voucher program in 2021 and legislation was filed to expand the program before the state Supreme Court struck it down for violating Kentucky’s constitution. That decision led directly to the legislature putting Amendment 2 on the ballot. Similar states that lack Kentucky’s constitutional protections for public education have recently increased spending on vouchers and school privatization at a rapidly growing cost to their budgets. Given that history and context, it is plausible to assume the legislature will pursue a similar path if voters approve the amendment.

This report estimates the impact, including by school district, if Amendment 2 is approved and the General Assembly enacts legislation to subsidize private schools using public funds. It models the impact of voucher legislation similar to recent expansions in several states. For Kentucky, establishing a program proportional to what Florida, the largest state program, has in place would cost $1.19 billion annually from the Kentucky state budget. That equals the cost of employing 9,869 Kentucky public school teachers and employees.

Even a much smaller initial voucher program just one-sixth the proportional size of Florida’s and smaller than the rapidly growing programs in Arizona, Indiana, Iowa, North Carolina, Ohio and Wisconsin would cost Kentucky’s budget $199 million, equivalent to the cost of employing 1,645 public school personnel. As this report shows, reduced state contributions to public school budgets are the expected source of funding for private school vouchers in Kentucky, meaning the numbers in this report reflect potential cuts to public school funding and staffing should voucher programs be allowed.

The report also finds:

- The recent experience of other states shows that 65%-90% of voucher costs go to subsidize families already sending their children to private schools or planning to do so — a group whose average household income in Kentucky is 54% higher than public school families. Providing vouchers to that group will easily cost the state hundreds of millions of dollars based on the number of Kentucky students already in private school.

- The cost of paying for vouchers will directly hit the state’s poorest rural areas the hardest because low property wealth makes them more dependent on state dollars for public education. These districts almost entirely lack private schools, and vouchers are unlikely to make setting up new private schools financially viable in many communities. The result will be tax dollars leaving these rural districts entirely, with local residents’ state taxes paying for private education elsewhere.

- The cost of private school subsidies will also be high in the state’s more populous counties, where public schools are more likely to face a second budgetary impact of a shift in enrollment to private schools and privately controlled charter schools. Local public schools will continue serving the vast majority of students and those with the greatest needs. They will also continue facing many of the same fixed costs, which cannot be reduced proportionately with a decline in the number of students. More money will be spent overall on duplicative administrative expenses across public and private systems rather than in the classroom where it is most needed. And schools will be increasingly segregated and unequal both racially and economically.

If Amendment 2 passes, it will upend Kentucky’s longstanding constitutional commitment to public education and result in legislation that diminishes public schools across the commonwealth. The amendment will widen the growing divides that are already weakening Kentucky communities and hinder education’s role in fostering the healthy democracy necessary for every Kentuckian to thrive.

Kentucky’s recent attempt at voucher programs and experience in similar states suggest what will likely follow if Amendment 2 passes

Amendment 2 is on the ballot because the Kentucky General Assembly’s prior attempt to allocate public money to private schools was struck down by the courts. In 2021, the legislature passed House Bill (HB) 563, legislation establishing a nearly dollar-for-dollar tax credit for donors to organizations that use the funds to provide private school scholarships.2 HB 563 was an attempt to get around Kentucky’s constitutional prohibition on spending public money for private schools by channeling the spending through the tax code instead of a direct appropriation.

Following a design similar to voucher programs in other states, the program was initially limited in a few ways. Private school tuition was an eligible expense in only eight counties, eligibility was restricted to an income level that included only the lowest-earning 63% of Kentucky households, the program was slated to sunset after five years, and the total program cost was capped at $25 million annually.3

A coalition of school districts and parents filed a lawsuit against HB 563, claiming that it violated the state’s constitutional provisions against public funding for private schools. The Franklin Circuit Court agreed with the plaintiffs, suspending HB 563 in 2021.

It is notable that the 2022 General Assembly considered expanding HB 563 only one year after its creation and while the program’s legal viability was still in question. Two bills were introduced that would have doubled or quadrupled the cost of the program, ended the five-year sunset, and increased income eligibility to 70%-77% of all families. Though neither bill moved forward while the program was in court, one of those proposals (HB 305) had 24 co-sponsors in the House of Representatives including the Speaker of the House.4

In December 2022, the Kentucky Supreme Court unanimously struck down HB 563, ruling that it violated Section 184 of the state constitution that says “no sum shall be raised or collected for education other than in the common schools” without a vote of the electorate.5 This decision meant the constitution would have to change for private school vouchers to be legal. The 2024 General Assembly then passed HB 2 putting Amendment 2 on the ballot this November.6

Tax credit scholarships like HB 563 are one of several typical forms of private school vouchers that 29 states now operate.7 Other versions include “education savings accounts” that put public funds into accounts families use to pay for private schools and other educational services, and traditional vouchers in which the government directly funds tuition and fees at private schools. Though the mechanisms vary, these policies are different means to the same end — publicly subsidizing private education. All three voucher types are being advanced by national organizations like EdChoice, which was the leading proponent of HB 563 in the Kentucky legislature and an advocate for HB 2.8

The history leading up to Amendment 2 indicates interest among a majority in the legislature to enact and expand private school vouchers and other forms of privatization. To understand the expected impact of the amendment in Kentucky, it is informative to look at the recent experience of those states that enacted school privatization programs during approximately the same time period as Kentucky but that did not face the same constitutional safeguards.

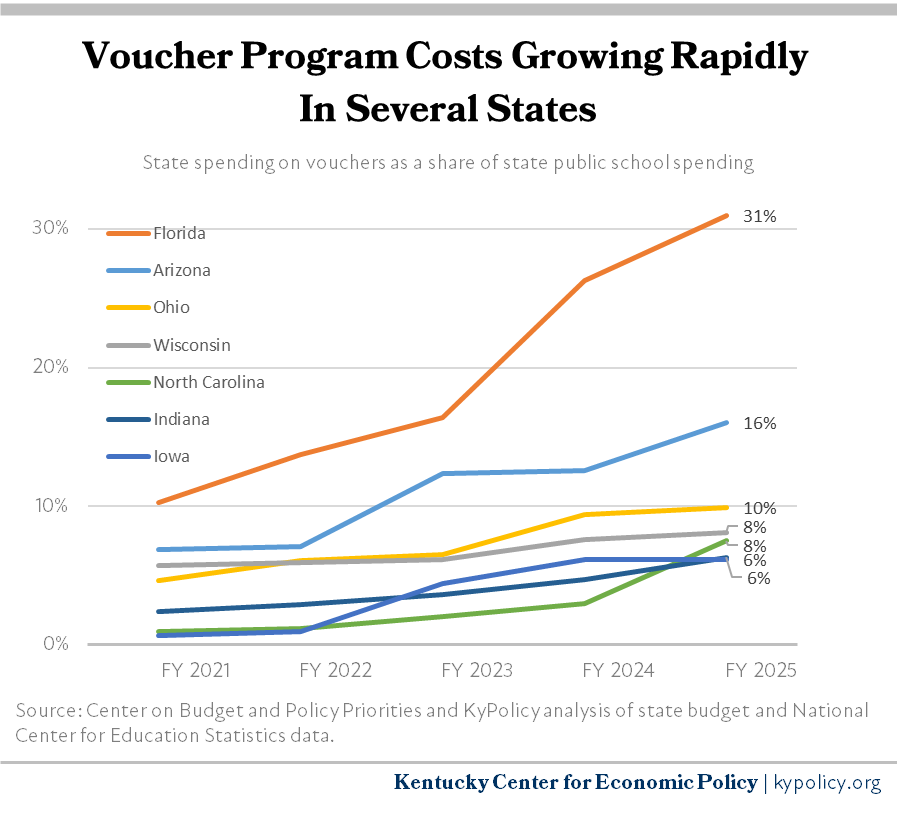

In the last few years, many jurisdictions have rapidly expanded their voucher programs, with 11 states now implementing programs with universal or near-universal income eligibility.9 The graph below shows the growth of voucher program costs as a share of what certain states spend on their public schools. Florida is now spending an estimated 31% of what it spends on public schools to support private school vouchers, while Arizona is spending 16%.10 Other states like Ohio, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Indiana and Iowa are substantially increasing their funding levels at a rate that may approach Arizona or even Florida if current trends continue.

Expanded vouchers primarily subsidize families already in private schools and benefit those who least need the help

The experience of other states also suggests who is likely to benefit from expanded private school voucher programs if Amendment 2 passes. Private school vouchers first subsidize families already sending kids to private schools or planning to do so.11 A review of the research found that between 65% and 90% of families receiving vouchers already had their children enrolled in private schools or were homeschooling or entering kindergarten, and journalistic accounts have confirmed these estimates.12 For example, in Indiana 67.5% of students receiving vouchers never attended public school.13

Private school voucher programs also tend to benefit families of greater means — those who can already afford private school — especially as income eligibility for these programs is expanded. In Arizona, which now has near-universal income eligibility, Brookings found that the lowest-poverty and highest-income communities have the greatest participation in the state’s education savings account program.14 Politico reported that after Florida increased income eligibility for its voucher program, newly-eligible higher-income families comprised over half of the enrollees.15

There are several reasons why better-off families are likely to benefit from voucher programs. Experience in other states shows that vouchers do not necessarily make often-expensive private school tuition affordable for many families who cannot make up the difference between the voucher and the cost of attendance. In fact, private schools have often increased tuition substantially after voucher programs went into effect.16 Lower-income families may be less aware of voucher programs and are likelier to face barriers to get to private schools, which often do not provide transportation. And the ability to exclude may make some families feel less welcome in certain private schools.

Because private schools are not public institutions, they can be exclusionary in ways other than cost. Vouchers have a troubling origin, arising in response to the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawing segregation in public schools. Private schools that receive vouchers can discriminate on the basis of religion, race, sexual orientation or gender identity, or because kids have a disability or special learning need.17 They choose their students, not the other way around.

In fact, Amendment 2 is written in a way that this kind of discrimination would be publicly funded should it pass. The Kentucky Supreme Court has ruled in the past that under the religious freedom clause of the state constitution (Section 5) the legislature is limited in the conditions and requirements it can place on private schools.18 Amendment 2 “notwithstands” seven portions of the state constitution to allow public dollars to go to private schools, but notably does not clarify how Section 5 applies to publicly-subsidized private schools. That makes it unlikely that the legislature could attach a provision prohibiting discrimination at private schools receiving public funding through state-funded vouchers.

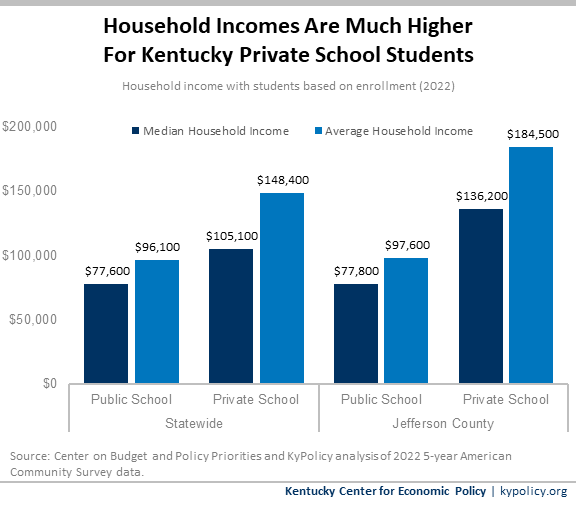

In Kentucky, families already sending their children to private schools — and therefore those most likely to benefit first from a voucher program — tend to be substantially better off financially than those in public schools. Statewide, the median household income of a public school child is $77,600 a year, while for a private school child it is $105,000. The gap is even wider in average income, reflecting the concentration of wealth at the top of the income scale. The average income is $96,100 for a public school household and $148,400 or 54% higher for a private school household. In Jefferson County, the average household with a private school student has an income of $184,500 annually.19

There are also major disparities in the racial makeup of public and private school students. According to Census data, in Jefferson County 48% of students in public school are white alone in their racial designation (and Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS) reports that 37% of their students are white non-Hispanic). However, 79% of students in private school in Jefferson County are white alone.20 For Kentucky as a whole, 78% of students in public schools are white alone compared to 86% of students in private schools.21

Existing private schools in Kentucky also tend to be concentrated in wealthier geographic locations. Just three counties are home to 53% of the state’s certified private schools (Jefferson County has 33% of existing private schools, Kenton County 11% and Fayette County 10%). In contrast, 63% of the state’s counties have zero private schools. And private school location is even more concentrated by neighborhood. A total of 80% of Kentucky’s private schools certified by the state are located in just 8% of the state’s zip codes.22

Because of the difficulty in funding and operating private schools without wealthy families that can pay tuition and make charitable contributions to school endowments, it is unlikely that many poor rural counties would be able to sustain private schools even with the support of a state-funded voucher program. In other states, new “pop-up” sub-prime private schools that appeared after voucher programs began have often failed after generating headlines for providing low-quality education.23

Funding of private school vouchers will harm already inadequate public school funding

It is reasonable to assume that funding for private school vouchers in Kentucky will come from funding for public schools, particularly if voucher funding levels grow over time as seen in other states. There are several reasons why.

First, public schools have long been the largest item in the Kentucky state budget, with funding typically in the range of 43% to 45% of state General Fund expenditures in most of recent history.24 If taxes are not raised, it is hard to enact substantial new public spending on vouchers without harming state public school spending to some degree. Appropriating monies for new spending while avoiding cuts to public school funding would require even larger cuts to other areas of the budget like Medicaid, postsecondary education, the criminal legal system, human services and infrastructure, all of which are supported by significant constituencies and many of which include federal funding that requires a state match.

Second, the legislature has already shown a willingness to shift away from public education as a state budget priority. Its share of the General Fund budget dropped from the 43% to 45% range mentioned above to 37%-39% in the last two budgets.25 Since the Great Recession, the legislature has substantially reduced funding for public education when taking inflation into account. In the recently-enacted budget, funding for the core school funding formula known as SEEK is an inflation-adjusted 26% below 2008 levels.26 That’s a gap of $1.1 billion, the approximate cost of a Florida-scale voucher program in Kentucky.

Other areas outside the core funding formula have also experienced cuts. In every year since 2005, the legislature has suspended the law requiring full state funding of school transportation, providing a lesser amount and leaving school districts to fill in the gaps as they are able with local resources. Despite record dollars in reserve, the recently enacted budget keeps funding frozen at 2019 levels for preschool and extended school services and the state has not provided any dedicated funding for textbooks or teacher professional development since 2018.27

Third, in 2022 the General Assembly passed legislation creating a formula to reduce the state’s individual income tax. Historically, the individual income tax is Kentucky’s largest revenue source, responsible for over 40% of the state’s General Fund budget. The General Assembly reduced the top rate from 6% to 5% in 2018 and then followed its formula to cut the rate to 4.5% in 2023 and 4% as of Jan. 1, 2024. While initially the legislature expanded the sales tax to offset some of the cost of reducing the income tax, the revenue losses from income tax rate reductions under the formula are increasingly not being offset with any tax increases. It is implausible to imagine that continued cuts to the individual income tax will not result in lower receipts that squeeze funding for public services including public schools. Adding the creation and expansion of state-funded private school vouchers will only increase the likelihood of public school funding cuts.

Finally, reduced funding for public schools has occurred in other states that increased funding for private school vouchers. Seven states that recently increased voucher spending also had declining state effort in funding their public schools, according to a study by the Southern Poverty Law Center.28 The Economic Policy Institute found that states with voucher programs spent $900 less per student on public education than states without vouchers in 2007, and $2,800 less per student by 2021.29

The cuts already made in funding for Kentucky’s public schools are causing major challenges for school districts in attracting and retaining critical personnel. The state has a growing teacher shortage, with more teachers leaving the profession and fewer entering the teacher education pipeline.30 A bus driver shortage fueled by state underfunding is leading to growing difficulty getting kids to and from school, a problem now at a crisis level in Jefferson County.31

Cuts following 2008 led to real harm to classroom and school services. A 2018 KyPolicy survey of school superintendents found that because of post-Great Recession state budget cuts, a majority of districts reduced days in the school calendar, 35% reduced or eliminated art and music programs, 30% cut course offerings, 35% increased fees, 42% reduced student supports including afterschool programs, and 25% spent less on health services.32 And state budget cuts have resulted in the gap in funding between wealthy and poor school districts now surpassing the levels declared unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court under the Rose decision in 1989.33

These cuts are happening despite growing evidence that providing more funding for public schools significantly improves the lives of children, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds.34 For example, one study found that between 1972 and 2010 an increase in school spending by 10% over a 12-year period resulted in 7% higher wages and 10% higher family incomes in adulthood.35

Vouchers will be expensive and siphon resources from rural schools in particular

A private school voucher program is likely to widen education divides in several ways. First, as mentioned above, the experience of other states shows it will primarily subsidize families who already have children enrolled in private schools, or are planning to, and have the resources to pay for it.

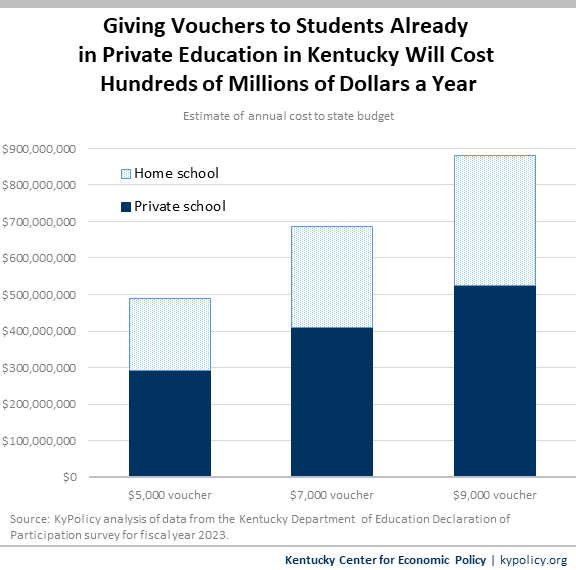

In 2023, there were an estimated 58,388 students in private school in Kentucky, in addition to approximately 39,534 who were homeschooled.36 While the cost of a voucher program would depend on its design, in a number of states vouchers are set at a level equal to or near state (or sometimes state and local) per pupil spending on public education.37 State spending for public education per pupil in Kentucky was $9,850 in 2023, and $7,092 minus state contributions to the Teachers Retirement System (a significant portion of which is catch-up payments for past unfunded liabilities). In the table below, we estimate the potential cost of a voucher program at $5,000, $7,000 and $9,000 per student, estimates that somewhat conservatively approximate other states’ voucher programs. The cost of subsidizing all existing Kentucky private school and homeschool students at these levels ranges from $490 million to $881 million annually.

It is also possible to look at the impact on public school budgets at the district level under the plausible assumption that any new private school voucher program will be funded at the expense of state funding for public schools. In Appendix 1, we model the impact of a voucher program costing 5%, 15% and 30% of state public school funding. As mentioned above, these estimates align with what other states are already spending.

These estimates are localized based on the share of school district funding that comes from the state budget and are then converted to a proportional number of teachers and other school personnel including bus drivers, cafeteria workers and counselors. Employees make up approximately 84% of school district spending, so it is difficult to make significant cuts to public education without reducing the number of personnel either through layoffs or attrition.38

As the data show, a statewide private school voucher program of 5%, 15% and 30% of state public school spending would cost an estimated $199 million to $1.19 billion annually. Note these amounts are similar to the estimated cost of merely subsidizing students already in private school or home school described above, and so could be reached before a single student leaves public schools. An Arizona-scale program costing 15% of state spending would cost enough to reduce total school district spending on average by 7%, while a Florida-like program costing 30% of state public school spending would equal 13% of total school district spending. A proportional cut in school district personnel to pay for a private school voucher program that costs 30% of state public school spending would reduce staffing in public schools by up 9,869 positions, 5,322 of which are teachers. See the map below and the report appendix for impacts by each Kentucky school district.

These impacts would be disproportionately larger in poorer rural counties with lower local property wealth from which to generate school tax revenue. For the wealthiest school district (Anchorage Independent), a Florida-scale private school voucher program costing approximately 30% of state school spending would reduce the district budget by 6%. In contrast, the same cut would reduce the district budget by at least 20% in a number of county school districts: Breathitt, Elliott, Estill, Letcher, McCreary, Morgan, Whitley and Wolfe, along with the independent districts in Cloverport, Corbin, East Bernstadt, Harlan, Hazard and Raceland. These districts and others in poorer rural areas in eastern and western Kentucky typically have no private schools that would benefit from vouchers, and opening new private schools in these communities will be financially difficult even with a state subsidy. Instead, a private school voucher program funded through public school budget cuts is likely to pull resources out of these communities entirely.

Additional harms will hit districts that also lose students to private schools

There would be additional harmful impacts on public school budgets for districts where new policies result in a shift in enrollment to private schools and privately controlled charter schools. For students who leave for private schools, the public school district would lose per-pupil state funding through the SEEK formula for each student along with a portion of other state and federal dollars. For charter schools, under state law public school districts will also lose local per-pupil dollars generated from taxes raised by the elected school board. These revenue losses from charter schools are on top of the reduction of state revenues from the expansion of funding for voucher programs at the expense of public schools described in the previous section.

Students lost to private schools or charter schools are likely to be from more advantaged backgrounds for reasons described above, leaving the public school with a population that is more expensive to serve per student. The districts that are most likely to experience student population losses are in urban and suburban communities that tend to have more diverse student bodies often requiring greater resources per student due to societal and structural disadvantages. For example, in JCPS 21% of students are multilingual learners that speak over 150 different languages, the enrolled population includes 12,766 children with exceptional needs, and 66% of students are considered economically disadvantaged.39 Given the socioeconomic makeup of these communities, the local public schools will still serve the vast majority of students but will do so with significantly fewer resources.

In addition, districts will be left with the same or near the same fixed costs for expenses like facilities, technology, operations, debt service and more even while receiving less tax revenues. As the Shanker Institute notes, “districts pay the same price to keep a school heated in the winter regardless of whether 50 students are enrolled, or whether 10 students have left with a voucher and 40 classmates stay.”40 Other costs cannot be reduced proportionally to the number of students who leave for private schools; for example, a school cannot lay off a teacher if three students unenroll from a public school class. In a broader sense, more overall public dollars in a community will go to duplicative administrative costs across public and private systems as opposed to being dedicated to the classroom.41

Kentucky’s charter school law allows funds to be diverted from public schools to schools governed entirely by separate, unelected boards whose operations can be outsourced to private — including for-profit — service providers. The law lacks local democratic accountability in the 16 county school districts with an enrollment of at least 7,500 public school students, which collectively serve 47% of Kentucky public school students.42 Those districts can be required by the state Board of Education to share proportional local, state and federal funds based on enrollment or attendance with privately controlled charter schools even if the district does not endorse or agree to the arrangement.43

A yes vote in November will upend Kentucky’s constitutional commitment to public education

Kentucky stands out among states for its strong founding promise of public education as a right, and for its constitutional commitment to state responsibility for funding an “efficient system of common schools.”44 In the 1989 Rose decision that led to the Kentucky Education Reform Act, the Kentucky Supreme Court described what that pledge meant:

The system of common schools must be adequately funded to achieve its goals… [and] must be substantially uniform throughout the state. Each child, every child, in this Commonwealth must be provided with an equal opportunity to have an adequate education. Equality is the key word here. The children of the poor and the children of the rich, the children who live in the poor districts and the children who live in the rich districts must be given the same opportunity and access to an adequate education.

Amendment 2 would completely overturn that longstanding commitment. It will lead to policies that widen the geographic, income and racial divides already straining Kentucky communities; shift public money to unaccountable private schools; and weaken education for all by spreading scarce public dollars across multiple, duplicative administrative systems. Kentucky voters have good reason for concern about the aftermath if the amendment passes.

Appendix

| Estimated Harms to Kentucky School Districts from State Spending on Voucher Programs at the Expense of Public Education | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent reduction in total school district budget | Dollar reduction in total school district budget | Proportional loss of public school personnel | |||||||

| Reduction in state spending on public education to pay for voucher programs | -5% | -15% (Arizona-scale) | -30% (Florida-scale) | -5% | -15% | -30% | -5% | -15% | -30% |

| Adair County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$968,022 | -$2,904,067 | -$5,808,134 | -7 | -22 | -45 |

| Allen County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$1,043,237 | -$3,129,712 | -$6,259,424 | -9 | -27 | -53 |

| Anchorage Independent | -1% | -3% | -6% | -$88,739 | -$266,218 | -$532,435 | -1 | -2 | -4 |

| Anderson County | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$925,882 | -$2,777,645 | -$5,555,289 | -8 | -25 | -50 |

| Ashland Independent | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$1,145,382 | -$3,436,147 | -$6,872,294 | -11 | -32 | -65 |

| Augusta Independent | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$140,424 | -$421,273 | -$842,546 | -1 | -3 | -6 |

| Ballard County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$396,621 | -$1,189,863 | -$2,379,727 | -3 | -9 | -18 |

| Barbourville Independent | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$239,170 | -$717,511 | -$1,435,022 | -2 | -5 | -10 |

| Bardstown Independent | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$752,680 | -$2,258,040 | -$4,516,080 | -8 | -23 | -46 |

| Barren County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$1,811,262 | -$5,433,785 | -$10,867,571 | -16 | -47 | -93 |

| Bath County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$712,769 | -$2,138,308 | -$4,276,615 | -6 | -19 | -38 |

| Beechwood Independent | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$442,341 | -$1,327,023 | -$2,654,045 | -2 | -7 | -14 |

| Bell County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$1,027,343 | -$3,082,030 | -$6,164,060 | -8 | -25 | -49 |

| Bellevue Independent | -2% | -5% | -9% | -$157,235 | -$471,704 | -$943,407 | -1 | -4 | -7 |

| Berea Independent | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$436,329 | -$1,308,988 | -$2,617,976 | -4 | -11 | -22 |

| Boone County | -2% | -5% | -9% | -$4,213,083 | -$12,639,250 | -$25,278,500 | -34 | -103 | -206 |

| Bourbon County | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$735,567 | -$2,206,702 | -$4,413,403 | -7 | -21 | -42 |

| Bowling Green Independent | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$1,612,635 | -$4,837,905 | -$9,675,810 | -12 | -37 | -75 |

| Boyd County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$1,055,920 | -$3,167,759 | -$6,335,519 | -11 | -33 | -67 |

| Boyle County | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$930,107 | -$2,790,320 | -$5,580,639 | -7 | -22 | -44 |

| Bracken County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$439,303 | -$1,317,910 | -$2,635,821 | -4 | -13 | -26 |

| Breathitt County | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$860,457 | -$2,581,372 | -$5,162,744 | -6 | -17 | -35 |

| Breckinridge County | -2% | -7% | -15% | -$853,087 | -$2,559,260 | -$5,118,521 | -8 | -25 | -49 |

| Bullitt County | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$3,052,037 | -$9,156,112 | -$18,312,224 | -25 | -76 | -153 |

| Burgin Independent | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$140,165 | -$420,494 | -$840,989 | -1 | -4 | -7 |

| Butler County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$823,617 | -$2,470,850 | -$4,941,700 | -7 | -21 | -41 |

| Caldwell County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$643,762 | -$1,931,287 | -$3,862,573 | -6 | -19 | -37 |

| Calloway County | -2% | -6% | -13% | -$779,450 | -$2,338,351 | -$4,676,702 | -7 | -21 | -43 |

| Campbell County | -2% | -5% | -10% | -$1,109,720 | -$3,329,161 | -$6,658,323 | -9 | -27 | -55 |

| Campbellsville Independent | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$460,107 | -$1,380,322 | -$2,760,644 | -4 | -11 | -23 |

| Carlisle County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$300,601 | -$901,804 | -$1,803,608 | -3 | -9 | -19 |

| Carroll County | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$612,067 | -$1,836,200 | -$3,672,399 | -6 | -17 | -33 |

| Carter County | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$1,607,707 | -$4,823,120 | -$9,646,240 | -15 | -46 | -93 |

| Casey County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$868,983 | -$2,606,950 | -$5,213,900 | -8 | -24 | -48 |

| Caverna Independent | -2% | -5% | -11% | -$200,994 | -$602,981 | -$1,205,962 | -2 | -5 | -10 |

| Christian County | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$2,748,777 | -$8,246,330 | -$16,492,661 | -24 | -72 | -143 |

| Clark County | -2% | -6% | -13% | -$1,504,163 | -$4,512,489 | -$9,024,979 | -13 | -40 | -79 |

| Clay County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$1,262,662 | -$3,787,987 | -$7,575,974 | -11 | -33 | -67 |

| Clinton County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$645,933 | -$1,937,800 | -$3,875,601 | -6 | -17 | -34 |

| Cloverport Independent | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$153,048 | -$459,144 | -$918,288 | -1 | -4 | -8 |

| Corbin Independent | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$1,242,950 | -$3,728,849 | -$7,457,698 | -10 | -30 | -60 |

| Covington Independent | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$1,220,019 | -$3,660,056 | -$7,320,112 | -9 | -28 | -55 |

| Crittenden County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$454,195 | -$1,362,586 | -$2,725,172 | -5 | -14 | -29 |

| Cumberland County | -2% | -7% | -15% | -$346,117 | -$1,038,350 | -$2,076,700 | -3 | -10 | -20 |

| Danville Independent | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$604,494 | -$1,813,482 | -$3,626,964 | -5 | -15 | -31 |

| Daviess County | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$3,215,148 | -$9,645,444 | -$19,290,888 | -28 | -84 | -168 |

| Dawson Springs Independent | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$263,819 | -$791,457 | -$1,582,913 | -3 | -8 | -15 |

| Dayton Independent | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$327,835 | -$983,504 | -$1,967,008 | -3 | -8 | -16 |

| East Bernstadt Independent | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$221,049 | -$663,147 | -$1,326,295 | -2 | -6 | -13 |

| Edmonson County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$625,485 | -$1,876,456 | -$3,752,911 | -7 | -20 | -41 |

| Elizabethtown Independent | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$810,821 | -$2,432,463 | -$4,864,925 | -7 | -20 | -40 |

| Elliott County | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$423,724 | -$1,271,172 | -$2,542,344 | -4 | -12 | -24 |

| Eminence Independent | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$338,233 | -$1,014,700 | -$2,029,400 | -3 | -9 | -17 |

| Erlanger-Elsmere Independent | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$734,699 | -$2,204,096 | -$4,408,193 | -6 | -17 | -34 |

| Estill County | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$913,368 | -$2,740,104 | -$5,480,209 | -9 | -27 | -55 |

| Fairview Independent | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$276,471 | -$829,412 | -$1,658,823 | -2 | -7 | -14 |

| Fayette County | -1% | -4% | -8% | -$8,687,617 | -$26,062,850 | -$52,125,700 | -63 | -190 | -380 |

| Fleming County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$804,876 | -$2,414,627 | -$4,829,253 | -6 | -18 | -36 |

| Floyd County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$2,026,203 | -$6,078,610 | -$12,157,219 | -19 | -58 | -116 |

| Fort Thomas Independent | -2% | -6% | -13% | -$909,640 | -$2,728,921 | -$5,457,842 | -6 | -17 | -35 |

| Frankfort Independent | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$315,770 | -$947,311 | -$1,894,622 | -3 | -8 | -16 |

| Franklin County | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$1,742,609 | -$5,227,827 | -$10,455,653 | -15 | -45 | -90 |

| Fulton County | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$217,441 | -$652,323 | -$1,304,646 | -2 | -7 | -14 |

| Fulton Independent | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$126,327 | -$378,980 | -$757,959 | -1 | -4 | -7 |

| Gallatin County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$499,390 | -$1,498,170 | -$2,996,339 | -4 | -11 | -22 |

| Garrard County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$891,700 | -$2,675,099 | -$5,350,199 | -9 | -26 | -52 |

| Glasgow Independent | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$835,235 | -$2,505,705 | -$5,011,410 | -6 | -19 | -38 |

| Grant County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$1,263,051 | -$3,789,154 | -$7,578,308 | -11 | -32 | -64 |

| Graves County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$1,276,936 | -$3,830,809 | -$7,661,618 | -13 | -38 | -77 |

| Grayson County | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$1,352,337 | -$4,057,010 | -$8,114,020 | -12 | -36 | -73 |

| Green County | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$728,075 | -$2,184,226 | -$4,368,452 | -6 | -19 | -38 |

| Greenup County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$950,708 | -$2,852,124 | -$5,704,247 | -10 | -30 | -60 |

| Hancock County | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$526,913 | -$1,580,739 | -$3,161,477 | -5 | -14 | -28 |

| Hardin County | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$4,639,615 | -$13,918,846 | -$27,837,692 | -46 | -138 | -276 |

| Harlan County | -3% | -10% | -19% | -$1,570,911 | -$4,712,733 | -$9,425,465 | -14 | -41 | -82 |

| Harlan Independent | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$311,225 | -$933,674 | -$1,867,347 | -3 | -10 | -19 |

| Harrison County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$954,461 | -$2,863,383 | -$5,726,767 | -9 | -26 | -52 |

| Hart County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$999,345 | -$2,998,035 | -$5,996,070 | -8 | -25 | -50 |

| Hazard Independent | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$426,962 | -$1,280,886 | -$2,561,772 | -4 | -11 | -22 |

| Henderson County | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$2,241,268 | -$6,723,803 | -$13,447,606 | -22 | -66 | -131 |

| Henry County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$702,191 | -$2,106,572 | -$4,213,144 | -7 | -20 | -39 |

| Hickman County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$244,700 | -$734,100 | -$1,468,200 | -2 | -7 | -15 |

| Hopkins County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$2,147,975 | -$6,443,924 | -$12,887,848 | -20 | -61 | -122 |

| Jackson County | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$936,807 | -$2,810,420 | -$5,620,839 | -8 | -24 | -49 |

| Jackson Independent | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$127,500 | -$382,501 | -$765,002 | -1 | -4 | -8 |

| Jefferson County | -1% | -4% | -8% | -$20,059,537 | -$60,178,612 | -$120,357,223 | -132 | -396 | -792 |

| Jenkins Independent | -2% | -7% | -15% | -$185,077 | -$555,231 | -$1,110,463 | -1 | -4 | -8 |

| Jessamine County | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$2,337,634 | -$7,012,903 | -$14,025,806 | -23 | -68 | -135 |

| Johnson County | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$1,424,659 | -$4,273,976 | -$8,547,953 | -13 | -38 | -75 |

| Kenton County | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$3,426,389 | -$10,279,166 | -$20,558,332 | -25 | -76 | -152 |

| Knott County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$1,074,454 | -$3,223,361 | -$6,446,722 | -8 | -25 | -49 |

| Knox County | -3% | -10% | -19% | -$1,766,094 | -$5,298,283 | -$10,596,566 | -17 | -50 | -101 |

| LaRue County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$859,984 | -$2,579,953 | -$5,159,906 | -8 | -23 | -45 |

| Laurel County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$3,057,650 | -$9,172,951 | -$18,345,902 | -25 | -76 | -153 |

| Lawrence County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$858,665 | -$2,575,995 | -$5,151,989 | -9 | -26 | -52 |

| Lee County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$296,946 | -$890,838 | -$1,781,676 | -3 | -8 | -17 |

| Leslie County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$731,324 | -$2,193,971 | -$4,387,943 | -7 | -20 | -41 |

| Letcher County | -4% | -11% | -22% | -$1,822,202 | -$5,466,605 | -$10,933,211 | -12 | -36 | -72 |

| Lewis County | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$913,861 | -$2,741,583 | -$5,483,167 | -8 | -24 | -47 |

| Lincoln County | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$1,147,682 | -$3,443,047 | -$6,886,094 | -11 | -34 | -68 |

| Livingston County | -2% | -6% | -11% | -$289,700 | -$869,100 | -$1,738,201 | -3 | -9 | -17 |

| Logan County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$1,143,923 | -$3,431,768 | -$6,863,536 | -11 | -34 | -67 |

| Ludlow Independent | -2% | -7% | -15% | -$277,368 | -$832,104 | -$1,664,208 | -2 | -6 | -12 |

| Lyon County | -2% | -5% | -10% | -$205,079 | -$615,238 | -$1,230,476 | -2 | -6 | -12 |

| Madison County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$3,258,931 | -$9,776,793 | -$19,553,585 | -28 | -85 | -169 |

| Magoffin County | -3% | -10% | -19% | -$883,476 | -$2,650,428 | -$5,300,856 | -8 | -25 | -49 |

| Marion County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$953,674 | -$2,861,022 | -$5,722,044 | -8 | -24 | -47 |

| Marshall County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$1,326,702 | -$3,980,107 | -$7,960,214 | -12 | -35 | -70 |

| Martin County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$744,623 | -$2,233,869 | -$4,467,739 | -7 | -20 | -40 |

| Mason County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$877,330 | -$2,631,990 | -$5,263,981 | -7 | -22 | -44 |

| Mayfield Independent | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$914,085 | -$2,742,254 | -$5,484,508 | -8 | -25 | -49 |

| McCracken County | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$1,761,925 | -$5,285,774 | -$10,571,549 | -15 | -44 | -88 |

| McCreary County | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$1,145,465 | -$3,436,396 | -$6,872,791 | -11 | -32 | -65 |

| McLean County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$483,077 | -$1,449,230 | -$2,898,460 | -5 | -16 | -32 |

| Meade County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$1,633,523 | -$4,900,568 | -$9,801,135 | -16 | -47 | -94 |

| Menifee County | -3% | -10% | -19% | -$460,135 | -$1,380,405 | -$2,760,810 | -4 | -12 | -24 |

| Mercer County | -2% | -7% | -15% | -$891,181 | -$2,673,542 | -$5,347,084 | -7 | -22 | -44 |

| Metcalfe County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$549,738 | -$1,649,213 | -$3,298,425 | -4 | -13 | -25 |

| Middlesboro Independent | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$376,241 | -$1,128,722 | -$2,257,443 | -3 | -9 | -18 |

| Monroe County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$697,284 | -$2,091,853 | -$4,183,707 | -7 | -21 | -43 |

| Montgomery County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$1,510,739 | -$4,532,218 | -$9,064,436 | -14 | -42 | -84 |

| Morgan County | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$911,959 | -$2,735,876 | -$5,471,752 | -8 | -25 | -50 |

| Muhlenberg County | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$1,538,511 | -$4,615,534 | -$9,231,069 | -14 | -43 | -86 |

| Murray Independent | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$610,184 | -$1,830,553 | -$3,661,107 | -7 | -21 | -41 |

| Nelson County | -2% | -5% | -10% | -$1,040,629 | -$3,121,886 | -$6,243,773 | -9 | -27 | -53 |

| Newport Independent | -1% | -4% | -9% | -$385,816 | -$1,157,449 | -$2,314,899 | -3 | -9 | -17 |

| Nicholas County | -3% | -9% | -19% | -$431,656 | -$1,294,967 | -$2,589,935 | -3 | -10 | -20 |

| Ohio County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$1,414,315 | -$4,242,944 | -$8,485,889 | -15 | -45 | -90 |

| Oldham County | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$3,328,615 | -$9,985,845 | -$19,971,689 | -23 | -70 | -139 |

| Owen County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$640,702 | -$1,922,107 | -$3,844,215 | -5 | -16 | -33 |

| Owensboro Independent | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$1,741,996 | -$5,225,989 | -$10,451,978 | -17 | -51 | -102 |

| Owsley County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$301,964 | -$905,891 | -$1,811,782 | -3 | -8 | -17 |

| Paducah Independent | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$979,592 | -$2,938,776 | -$5,877,552 | -7 | -20 | -40 |

| Paintsville Independent | -3% | -8% | -15% | -$267,696 | -$803,087 | -$1,606,173 | -2 | -6 | -12 |

| Paris Independent | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$255,847 | -$767,541 | -$1,535,083 | -2 | -6 | -13 |

| Pendleton County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$832,572 | -$2,497,717 | -$4,995,434 | -6 | -19 | -39 |

| Perry County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$1,601,589 | -$4,804,766 | -$9,609,533 | -13 | -39 | -78 |

| Pike County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$3,122,591 | -$9,367,773 | -$18,735,547 | -26 | -79 | -158 |

| Pikeville Independent | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$318,045 | -$954,136 | -$1,908,271 | -2 | -7 | -15 |

| Pineville Independent | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$237,222 | -$711,666 | -$1,423,332 | -2 | -5 | -10 |

| Powell County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$801,926 | -$2,405,778 | -$4,811,557 | -8 | -23 | -46 |

| Pulaski County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$2,581,216 | -$7,743,647 | -$15,487,293 | -24 | -72 | -143 |

| Raceland Independent | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$466,850 | -$1,400,549 | -$2,801,099 | -4 | -11 | -22 |

| Robertson County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$220,007 | -$660,020 | -$1,320,040 | -1 | -4 | -9 |

| Rockcastle County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$1,066,703 | -$3,200,109 | -$6,400,219 | -10 | -30 | -60 |

| Rowan County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$1,063,436 | -$3,190,309 | -$6,380,618 | -9 | -27 | -53 |

| Russell County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$1,080,246 | -$3,240,737 | -$6,481,474 | -11 | -32 | -64 |

| Russell Independent | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$685,710 | -$2,057,131 | -$4,114,261 | -6 | -18 | -36 |

| Russellville Independent | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$404,685 | -$1,214,055 | -$2,428,110 | -4 | -11 | -21 |

| Science Hill Independent | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$154,836 | -$464,509 | -$929,018 | -2 | -5 | -10 |

| Scott County | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$2,603,413 | -$7,810,239 | -$15,620,478 | -24 | -72 | -145 |

| Shelby County | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$1,850,914 | -$5,552,743 | -$11,105,486 | -15 | -44 | -89 |

| Simpson County | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$842,832 | -$2,528,497 | -$5,056,993 | -8 | -23 | -46 |

| Somerset Independent | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$499,726 | -$1,499,177 | -$2,998,354 | -4 | -11 | -23 |

| Southgate Independent | -2% | -5% | -10% | -$57,264 | -$171,791 | -$343,583 | -1 | -2 | -4 |

| Spencer County | -2% | -7% | -15% | -$923,314 | -$2,769,942 | -$5,539,884 | -9 | -26 | -53 |

| Taylor County | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$971,055 | -$2,913,164 | -$5,826,329 | -8 | -24 | -49 |

| Todd County | -3% | -8% | -17% | -$681,417 | -$2,044,251 | -$4,088,502 | -7 | -21 | -41 |

| Trigg County | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$580,290 | -$1,740,870 | -$3,481,740 | -5 | -16 | -32 |

| Trimble County | -2% | -6% | -12% | -$336,842 | -$1,010,527 | -$2,021,054 | -3 | -8 | -16 |

| Union County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$1,116,902 | -$3,350,706 | -$6,701,411 | -8 | -23 | -46 |

| Walton Verona Independent | -2% | -6% | -13% | -$547,252 | -$1,641,755 | -$3,283,510 | -4 | -12 | -24 |

| Warren County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$4,513,013 | -$13,539,039 | -$27,078,078 | -42 | -125 | -251 |

| Washington County | -2% | -7% | -14% | -$543,781 | -$1,631,342 | -$3,262,684 | -5 | -14 | -28 |

| Wayne County | -3% | -9% | -18% | -$1,261,423 | -$3,784,269 | -$7,568,539 | -11 | -34 | -68 |

| Webster County | -3% | -9% | -17% | -$767,463 | -$2,302,390 | -$4,604,781 | -8 | -23 | -47 |

| Whitley County | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$1,717,318 | -$5,151,954 | -$10,303,909 | -17 | -52 | -103 |

| Williamsburg Independent | -3% | -10% | -19% | -$319,549 | -$958,647 | -$1,917,295 | -3 | -8 | -17 |

| Williamstown Independent | -3% | -8% | -16% | -$321,434 | -$964,302 | -$1,928,603 | -3 | -8 | -15 |

| Wolfe County | -3% | -10% | -20% | -$601,546 | -$1,804,638 | -$3,609,277 | -5 | -16 | -31 |

| Woodford County | -2% | -5% | -10% | -$869,054 | -$2,607,162 | -$5,214,323 | -7 | -22 | -45 |

| Total | -2% | -7% | -13% | -$199,136,878 | -$597,410,634 | -$1,194,821,267 | -1,645 | -4,934 | -9,869 |

| Source: KyPolicy analysis of Kentucky Department of Education data. State revenues include SEEK, non-SEEK and on-behalf revenues except payments to the Teachers' Retirement System because the latter is primarily made up of catch-up unfunded liability payments. Total school budget revenues exclude ESSER I, ESSER II and ARP ESSER pandemic expenditures because of their one-time nature, and other revenue that can be highly variable. Estimates for loss of personnel include both certified and classified staff, are based on head count, and are assumed to be proportional to the percent reduction in the total school district budget. | |||||||||

- House Bill 2, 2024 Regular Session of the Kentucky General Assembly, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/24rs/hb2.html. The amendment will read: “To give parents choices in educational opportunities for their children, are you in favor of enabling the General Assembly to provide financial support for the education costs of students in kindergarten through 12th grade who are outside the system of common (public) schools by amending the Constitution of Kentucky as stated below?

The General Assembly may provide financial support for the education of students outside the system of common schools. The General Assembly may exercise this authority by law, Sections 59, 60, 171, 183, 184, 186 and 189 of this Constitution notwithstanding.”

- House Bill 563, 2021 regular session of the Kentucky General Assembly, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/21rs/hb563.html.

- The income eligibility level in HB 563 is below 175% of eligibility for free and reduced lunch or $85,500 for a family of four, which equals approximately 63% of Kentucky families with school-age children. Anna Baumann, “HB 563 Diverts Public School Dollars to Unaccountable Private Entities,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 24, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/hb-563-diverts-public-school-dollars-to-unaccountable-private-entities/.

- House Bill 305, 2022 regular session of the Kentucky General Assembly, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/hb305.html. Senate Bill 50, 2022 regular session of the Kentucky General Assembly, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/sb50.html. Anna Baumann and Pam Thomas, “3 Ways New Legislation Would Make Kentucky’s Unconstitutional Voucher Program Even Worse,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 19, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/new-legislation-would-make-kentuckys-unconstitutional-school-voucher-program-even-worse/.

- Cameron v. Johnson et al., Dec. 15, 2022, http://opinions.kycourts.net/sc/2021-SC-0522-tg.pdf.

- House Bill 2, 2024 regular session of the Kentucky General Assembly, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/24rs/hb2.html. The legislature also attempted to establish charter schools, but no charter schools have been approved and that legislation is also in the courts based on similar arguments.

- Libby Stanford et al., Which States Have Private School Choice?” Education Week, May 8, 2024, https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/which-states-have-private-school-choice/2024/01.

- Kentucky Legislative Ethics Commission, “Kentucky Registered Employer Bill Numbers, May 9, 2024,” https://klec.ky.gov/Reports/Reports/lecbills2024.pdf.

- Samuel E. Abrams and Steven J. Koutsavlis, “The Fiscal Consequences of Private School Vouchers,” Southern Poverty Law Center, March 2023, https://pfps.org/assets/uploads/SPLC_ELC_PFPS_2023Report_Final.pdf. NEAToday, “’No Accountability’: Vouchers Wreak Havoc on States,” Feb. 2, 2024, https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/no-accountability-vouchers-wreak-havoc-states. Lane Wendell Fischer, “Republicans Double Down on School Vouchers by Taking Fight to Rural Members of Their Own Party,” Daily Yonder, May 8, 2024, https://dailyyonder.com/republicans-double-down-on-school-vouchers-by-taking-fight-to-rural-members-of-their-own-party/2024/05/08/. Iris Hinh and Whitney Tucker, “State Policymakers Are Draining Public Revenues with School Vouchers,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 12, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/state-lawmakers-are-draining-public-revenues-with-school-vouchers. Nina Mast, “State and Local Experience Proves School Vouchers Are a Failed Policy that Must Be Opposed,” Economic Policy Institute, April 20, 2023, https://www.epi.org/blog/state-and-local-experience-proves-school-vouchers-are-a-failed-policy-that-must-be-opposed-as-voucher-expansion-bills-gain-momentum-look-to-public-school-advocates-for-guidance/.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of state budget data.

- Mark Lieberman, “Most Students Getting New School Choice Funds Aren’t Ditching Public Schools,” Education Week, Oct. 4, 2023, https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/most-students-getting-new-school-choice-funds-arent-ditching-public-schools/2023/10.

- Josh Cowen, “NEPC Review: The Reality of Switcher,” National Education Policy Center, May 2024, https://nepc.colorado.edu/sites/default/files/reviews/NR%20Cowen_8.pdf. Gloria Rebecca Gomez, “Private School Students Flock to Expanded School Voucher Program,” AZ Mirror, Sept. 1, 2022, https://azmirror.com/2022/09/01/private-school-students-flock-to-expanded-school-voucher-program/.

- Indiana Department of Education, “Choice Scholarship Program Annual Report, Participation and Payment Data: 2023-2024,” https://www.in.gov/doe/files/2023-2024-Annual-Choice-Report.pdf.

- Brookings, “Arizona’s ‘Universal’ Education Savings Account Program Has Become a Handout for the Wealthy,” May 7, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/arizonas-universal-education-savings-account-program-has-become-a-handout-to-the-wealthy/.

- Andrew Atterbury, “GOP states are embracing vouchers. Wealthy parents are benefitting,” Politico, November 22, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/11/22/inside-school-voucher-debate-00128377.

- Jason Fontana and Jennifer L. Jennings, “The Effect of Taxpayer-Funded Education Savings Accounts on Private School Tuition: Evidence from Iowa,” EdWorking Paper 24-949, https://edworkingpapers.com/index.php/ai24-949. Neal Morton, “Arizona gave families public money for private schools. Then private schools raised tuition,” The Hechinger Report, Nov. 27, 2023, https://hechingerreport.org/arizona-gave-families-public-money-for-private-schools-then-private-schools-raised-tuition/.

- Chris Ford, et al., “The Racist Origins of Private School Vouchers,” Center for American Progress, July 12, 2017, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/racist-origins-private-school-vouchers/. Bayliss Fiddiman and Jessica Yin, “The Danger Private School Voucher Programs Pose to Civil Rights,” Center for American Progress, May 13, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/danger-private-school-voucher-programs-pose-civil-rights/.

- Kentucky State Board for Elementary and Secondary Education v. Rudasill, Oct. 9, 1979.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and KyPolicy analysis of 2022 5-year American Community Survey data.

- Kentucky Department of Education, School Report Card 2022-2023, Jefferson County, https://www.kyschoolreportcard.com/organization/5590/school_overview/students/enrollment?year=2023.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and KyPolicy analysis of 2022 5-year American Community Survey data.

- KyPolicy analysis of Kentucky Board of Education directory of certified non-public schools, https://www.education.ky.gov/federal/fed/Pages/Non-Public-Schools.aspx.

- Network for Public Education, “Voucher Scandals,” https://networkforpubliceducation.org/voucher-scandals/.

- Jason Bailey and Pam Thomas, “Public Schools Are Becoming a Lower State Budget Priority,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, May 9, 2023, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-public-school-funding/.

- Bailey and Thomas, “Public Schools Are Becoming.” 2024-2026 Budget of the Commonwealth Budget in Brief, https://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Documents/Budget%20Documents/2024-2026%20Budget%20of%20the%20Commonwealth/2024-2026%20Budget%20of%20the%20Commonwealth%20-%20Budget%20in%20Brief.pdf.

- Jason Bailey, et al., “Budget Agreement Maintains Modest Spending for Education and Other Needs Despite Funds Available to Do More,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, April 16, 2024, https://kypolicy.org/budget-agreement-maintains-modest-spending-for-education-and-other-needs-despite-funds-available-to-do-more/.

- Bailey, et al., “Budget Agreement Maintains Modest Spending.”

- Abrams and Koutsavlis, “The Fiscal Consequences of Private School Vouchers.”

- Hilary Wething and Josh Bivens, “Vouchers Undermine Efforts to Provide an Excellent Public Education for All,” Economic Policy Institute, May 15, 2024, https://www.epi.org/blog/vouchers-undermine-efforts-to-provide-an-excellent-public-education-for-all/.

- Legislative Research Commission Office of Education Accountability, “Kentucky Public School Employee Staffing Shortages,” November 1, 2023, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/117/26654/01Nov2023%20-%203%20-%20OEA%20Staffing%20Shortages.pdf. Jason Bailey, “State Report Describes Growing Educator Shortage, and Lack of Funding Plays a Key Role,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, November 3, 2023, https://kypolicy.org/state-report-on-kentucky-teacher-shortage/.

- Jason Bailey, “The Legislature’s Transportation Budget Cuts Contributed to the JCPS Bus Debacle,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 17, 2023, https://kypolicy.org/the-legislatures-transportation-budget-cuts-contributed-to-the-jcps-bus-debacle/.

- Ashley Spalding, “State Budget Cuts to Education Hurt Kentucky’s Classrooms and Kids,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 2018, https://kypolicy.org/state-budget-cuts-education-hurt-kentuckys-classrooms-kids/.

- Jason Bailey, et al., “The Funding Gap Between Kentucky’s Wealthy and Poor School Districts Is Now Worse than Levels Declared Unconstitutional,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 23, 2023, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-school-funding-returns-to-pre-kera-levels/.

- Wething and Bivens, “Vouchers Undermine Efforts.” Northwestern University Institute for Policy Research, “The Benefits of Increased School Spending,” March 2017, https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/policy-briefs/school-spending-policy-research-brief-Jackson.pdf. Carme Martin, et al., “A Quality Approach to School Funding,” Center for American Progress, Nov. 13, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/quality-approach-school-funding/. C. Kirabo Jackson and Claire L. Mackevicius, “What Impacts Can We Expect from School Spending Policy? Evidence from Evaluations in the United States,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, January 2024, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.20220279. Hosung Sohn, et al., “The Effect of Extra School Funding on Students’ Academic Achievements Under a Centralized School Financing System,” Education Finance and Policy, 2023, https://direct.mit.edu/edfp/article/18/1/1/109966/The-Effect-of-Extra-School-Funding-on-Students.

- C. Kirabo Jackson, et al., “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Feb. 2016, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/131/1/157/2461148?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false.

- Estimates are from the Kentucky Department of Education Declaration of Participation survey. Comparable private school estimates come from the National Center for Education Statistics’ Private School Universe Survey, which reports 56,749 private school students enrolled in Kentucky in fiscal year 2022. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pss/.

- Education Commission of the States, “Private Schol Choice: Vouchers 2024 50-State Comparison,” https://reports.ecs.org/comparisons/private-school-choice-vouchers-2024-07, EdChoice, “The ABCs of School Choice,” 2024 Edition, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2024-ABCs-of-School-Choice.pdf.

- Kentucky Department of Education, School Report Card 2021-2022, https://www.kyschoolreportcard.com/organization/20/financial_transparency/spending/spending_per_student?year=2022.

- Krista Johnson, “’Enormous Increase’: JCPS Tested by Sharp Rise in Students Who Don’t Speak English,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 26, 2024, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/education/2024/05/26/jcps-tested-by-sharp-rise-in-foreign-born-students-who-dont-speak-english/72497149007/. Jefferson County Public Schools, Popular Annual Financial Report 2022-2023, https://core-docs.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/documents/asset/uploaded_file/4298/JCPS/4061949/PAFR_2023_Final.pdf. Kentucky Department of Education, School Report Card 2022-2023.

- Josh Cowen, “How Do Vouchers Defund Public Schools? Four Warnings and One Big Takeaway,” Albert Shanker Institute, May 15, 2024, https://www.shankerinstitute.org/blog/vouchers-defund-public-schools.

- In the Public Interest, “Charter Schools and Fiscal Impact,” May 2023, https://inthepublicinterest.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/0523-Fiscal-Impact.4.pdf, Gordon Lafer, “Breaking Point: The Cost of Charter Schools for Public School Districts,” In the Public Interest, May 2018, https://www.inthepublicinterest.org/wp-content/uploads/ITPI_Breaking_Point_May2018FINAL.pdf.

- KyPolicy analysis of Kentucky Department of Education 2023 average annual daily attendance data.

- A charter school is not required to reach a memorandum of understanding with a local school district that endorses the application in districts of at least 7,500 enrolled students. KRS 160.1593(3)(f)(3), https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=53117. In addition, the mayors of Lexington or Louisville can authorize charter schools in their counties without the elected school board having any role in oversight of the charter school. KRS 160.1590(15), https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=53114.

- Derek W. Black, Schoolhouse Burning: Public Education and the Assault on Democracy, Public Affairs, 2020. Rose v. Council for Better Education, Sept. 28, 1989, https://nces.ed.gov/edfin/pdf/lawsuits/Rose_v_CBE_ky.pdf.