Paid parental leave has countless benefits for workers, children and families. It is also critical to attracting and retaining a high-quality workforce. A growing number of employers across Kentucky recognize this reality, with large private companies such as Amazon and Norton Healthcare, along with public entities such as Louisville Metro Government and Fayette County Public Schools providing paid parental leave to employees who welcome a child to their family.

But Kentucky’s 33,000 state employees have no such benefit. When their families grow, they are forced to use paid sick leave or vacation time they may have accumulated or take unpaid leave if they wish to spend time at home with their new child. In some cases, they may simply take no leave at all. This shortcoming creates challenges for growing families and contributes to employee turnover and already severe hiring difficulties in state government.1 When state government is short-staffed, Kentuckians’ access to public services such as child welfare or unemployment becomes less efficient, and maintenance of public infrastructure is hindered. This situation can and should be corrected through an administrative regulation through the personnel cabinet, or through legislation, such as what was proposed in Senate Bill (SB 142) during the 2024 Kentucky General Assembly. In either case, despite the many benefits, it would require minimal state investment.2

Many employers that compete with state government for employees offer paid parental leave

Many Kentucky employers competing with the state to attract and retain workers already offer competitive benefit packages that provide paid time off for employees welcoming new children into their families.3 These employers include public and private universities, local governments, public school systems, hospitals and large private companies. Paid leave policies are especially common at employers similar to state government in that they have large workforces and a significant share of jobs filled by workers with college degrees. This imbalance puts the state at a disadvantage when it comes to hiring and retaining workers. Younger people, especially those planning to have families, will likely consider the state’s paid leave policies as they decide if they should enter a career in state government or pursue other options. Similar Kentucky employers with paid parental leave policies include:

- Northern Kentucky University, Bellarmine University, the University of Kentucky and the University of Louisville are among the state’s higher education institutions that offer paid parental leave to their employees.4 Northern Kentucky University provides six weeks of paid leave to full-time employees after the birth, adoption or foster care placement of a new child. A representative from its human resources department described the policy as “well received” by employees since its implementation in 2022 and said most new hires expect this benefit or something similar.5

- Since July of 2021, Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government has offered employees four weeks of fully paid leave following a birth or adoption and two weeks of paid leave for employees accepting foster care placements. Administrators have seen the value of the policy and are considering expanding the four weeks of leave to all qualifying events, including foster care placements.6

- Since December 2022, the City of Frankfort has provided six weeks of fully paid leave for its employees welcoming new children through birth, adoption, foster care, or surrogacy.7

- Since July 2021, Louisville Metro Government has provided 12 weeks of paid leave to its employees welcoming a child through birth or adoption and two weeks to those accepting a child in foster care.8

- Norton Healthcare and UK Healthcare offer four and two weeks of paid parental leave, respectively.9The public school districts of Jefferson, Fayette, Franklin and Oldham counties have added paid family leave policies — all in the last two years.10

- Large private companies Amazon, Humana, Ford and Lexmark offer paid parental leave benefits.11 Amazon offers up to 20 weeks of fully paid time off for birthing parents and up to six weeks of paid parental leave to supporting parents following births or adoption.12

A paid parental leave policy for state workers would put Kentucky more in line with other states

While many workers are entitled to take unpaid parental leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), there is currently no federal law guaranteeing access to paid parental leave in either the public or the private sector. At least 13 states and Washington D.C. have enacted legislation to create mandatory paid parental leave programs for all employees, which typically operate either through social or private insurance systems.13 As of the beginning of 2024, 38 states had a paid parental leave policy for state government employees — with Kentucky remaining one of the 12 that do not.14

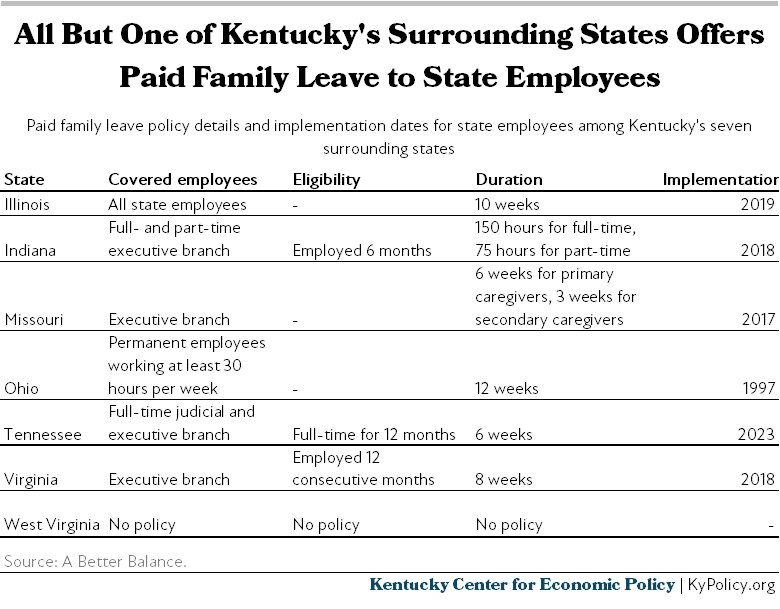

Six of Kentucky’s seven surrounding states provide paid parental leave to state employees, with all but one implementing its policy within the past decade.15 This advantage allows even these state governments to compete with Kentucky for skilled employees.

Kentucky’s 2024 legislative session saw the passage of House Bill (HB) 179, adding Kentucky to the list of states allowing for paid parental leave insurance plans to be sold and used in the commonwealth.16 While this law was needed to allow for the sale of this particular kind of product, it is not clear how many employers would use or even need such a tool to be able to provide paid leave for their employees. In the end, Kentucky has no paid parental leave policy for its state employees expecting new family additions.

Paid leave is good for newborns and their families

In addition to the workforce benefits inherent in a paid parental leave policy, allowing parents the time and pay to stay home with their newborns offers a host of physical, cognitive, psychological and economic benefits for children, mothers and fathers.

Infants in households that use paid parental leave end up with higher rates of vaccination, higher rates of breast-feeding (which is associated with better immunity development), and lower rates of childhood obesity, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and hearing-related problems in elementary school.17 One study found a correlation between paid parental leave and reduced infant hospitalizations, especially when compared to other states not providing leave.18 Another study showed that children eight weeks old and younger in a state with paid parental leave had 18% fewer hospitalizations for respiratory infections, and lower rates of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) infections than in similar states that don’t offer that benefit.19

Because brain development is so rapid in the earliest years of life, paid parental leave also has significant benefits to a child’s cognitive well-being. Research of three-month-old infants’ brain functionality showed more mature levels of development among children in households that used paid parental leave than similar children whose households did not.20 A separate study suggests that paid leave for new mothers is associated with better language outcomes for their children, and fewer behavioral challenges among children of mothers of lower educational attainment.21

Mothers who use paid parental leave also benefit greatly, as the paid time off to care for and bond with their children is associated with positive effects on many aspects of mothers’ health, including their physical, mental, and economic well-being.22 A study of women who gave birth in 2011 and 2012 found that mothers who used paid leave had a 51% lower chance of being re-hospitalized at 21 months post-partum and were 1.8-times more likely to consistently exercise and manage their stress than similar mothers without paid parental leave.23 Longer periods of paid parental leave also have been shown to benefit the reduction of mothers’ blood pressure, pain levels and smoking behaviors.24 Additionally, one review of 23 studies of paid parental leave policies found that paid and longer leave periods are associated with lower rates of postpartum depression.25 Another study found that mothers in Australia who had paid leave of at least 13 weeks reported less psychological distress two to three years after birth than mothers who had less than that, suggesting longer-term benefits for mothers’ mental health.26 State leave programs also boost individual and familial economic security, including by reducing the likelihood that new mothers would fall into poverty and by increasing household incomes.27

Studies also show paid parental leave is very important for fathers. More time spent with their young children has been shown to increase brain activity in adults in the parts of the brain associated with empathy.28 Paid parental leave for fathers can also contribute to longer-term involvement from fathers in their children’s lives.29 Another study of fathers in four countries found that the availability of paid paternal leave resulted in more time between fathers and their newborn children and a higher likelihood they would participate in caregiving activities for young children. The study also showed that quality time between the fathers and children was modestly associated with higher scores on cognition tests among their children later in life.30

Implementing a paid parental leave policy for state employees could reduce existing racial disparities in access as well. Nationally, Black and Hispanic mothers tend to have less access to paid parental leave through their employers than non-Hispanic white and Asian mothers.31 These racial disparities are even stronger in nonunionized sectors (like Kentucky’s state government).32 While research has yet to fully understand the effects of disproportionate access to paid leave by race, the literature overwhelmingly points to the health and economic benefits of paid parental leave.

Providing a paid parental leave policy would cost the state little-to-nothing and could lead to gains in employee retention and productivity

Paid parental leave policies have been shown to improve retention for early-to-mid career employees, saving the cost of re-hiring which can amount to 21% of a position’s salary.33 This cost calculation includes the initial expense of hiring a position and also factors in the lost expertise of the employee that leaves and the lower productivity that comes from training a new employee. An analysis of a state-level paid parental leave policies showed that mothers of one to three year-olds who utilized paid parental leave actually increased their work hours by 10-17% compared to mothers that did not.34 Additionally, having paid parental leave has been found to increase the probability of mothers returning to work within nine to 12 months following the birth of their child (rather than ending their employment), and working more hours and weeks of work during a child’s second year of life.35

While state government might be expected to face some additional costs associated with employee absence while they are on leave, the impact would likely be minimal. For a large employer like state government, duties can more easily be shared and shifted among other staff, as currently is the case when an employee uses sick time, takes vacation or goes on unpaid leave. Temporary staff would very rarely be needed or even possible given the degree of specialization many state government jobs require. State Police and Corrections staff may be an exception. In Lexington, when a paid parental leave benefit was implemented, police and firefighters taking paid parental leave did require some backfill of staffing at a minimal cost to the city.36

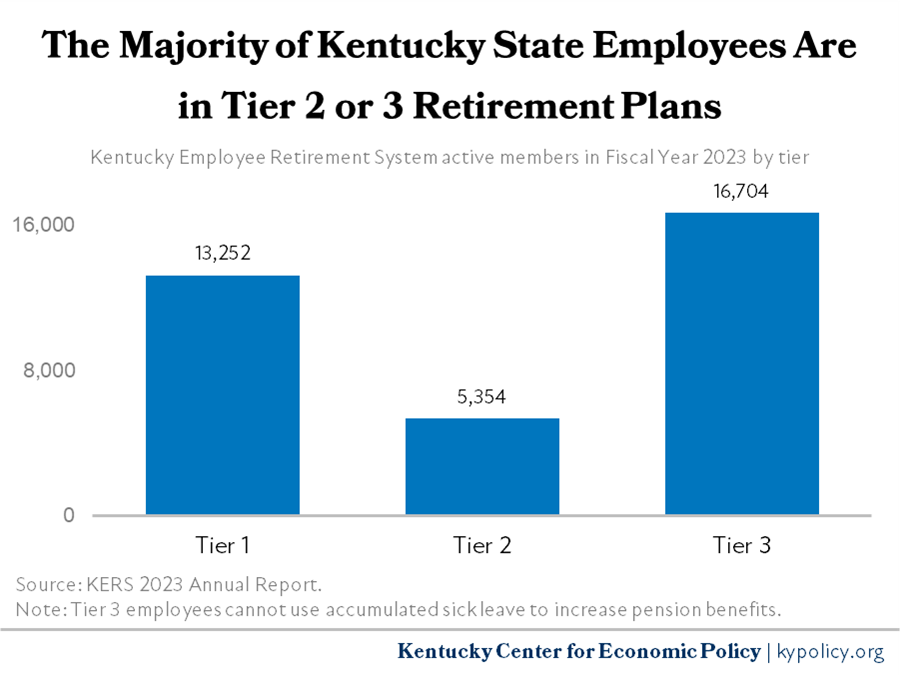

A more concrete potential cost could be the extra accumulated sick leave that employees would gain from being able to use parental leave rather than the sick days they currently use. Those employees could then retire with more sick days than they would have otherwise, and then convert that leave to service credit, increasing the value of their pension payments. However, only Tier 1 and Tier 2 employees in state government are eligible to use accumulated sick leave for service credit at retirement, and only 53% of active Kentucky Employees Retirement System (KERS) members fall into these categories.37 For Tier 1 employees, sick leave service credit counts toward retirement eligibility and health insurance benefits, and for Tier 2 employees sick leave only counts toward health insurance benefits and is capped at 12 months of service credit for unused time.

Moreover, many of the remaining Tier 1 and Tier 2 employees are beyond the age at which they are likely to take advantage of paid parental leave. Tier 1 employees had to be hired before Sept. 1, 2008, while Tier 2 employees must have been hired before Dec. 31, 2013. That means Tier 2 employees are likely to be in their early 30s at the youngest, and Tier 1 employees are likely at least in their late 30s. The median age of mothers at the time of their final birth is 31 years old, and the average age of parents at the time of adoption is 35 years old. Thus, the majority of state employees who are likely to use paid parental leave fall into Tier 3, hired on or after Jan. 1, 2014, and soon all eligible employees will be in Tier 3. Those employees will create no additional pension costs by the additional accumulation of paid sick leave.

Overall, the fiscal impact would be minimal and would eventually phase out entirely as the 5,354 Tier 2 employees age out of child-bearing years. The recruitment and retention benefits of paid parental leave for state employees would be permanent and increasingly important, helping the state to attract and retain a professional workforce.

Kentucky should move forward with a paid leave policy for state workers

In the 2024 General Assembly, Senate Bill 142 (SB 142) proposed a four-week leave for full-time state employees who had worked in state government for at least a year.38 This proposed leave could be used for births, adoptions and foster placements, and could only be used once per year. Under the bill, mothers and fathers could use the benefit. SB 142 made significant progress, passing out of the Senate 28-10, but it did not receive a committee hearing in the House and did not become law this session.

Introducing this legislation was an important step toward providing paid parental leave for state employees. However, there are a handful of key improvements to the proposed legislation that should be made whenever legislators or administration officials do adopt a state policy.

Most importantly, any paid parental leave policy needs to offer at least six weeks of full wage replacement, as is common in other similar employers as described above. Besides the intensive physical and emotional needs of newborn babies and their parents that extend well past that timeframe, a very practical issue is that child care providers will typically not accept children under six weeks old due to the need for full vaccination before participating in a communal setting. Given the existing shortage of child care providers, many of which do not care for infants, a six-week paid parental leave should be viewed as the minimum. Additionally, following policy adoption, the state should continue to allow parents to take more than six weeks if needed through either accumulated sick leave or through FMLA. State employees should be able to use this benefit once per year, as many parents have less than a 36 month gap between their first and second children.39

Including these elements in a permanent, statutory benefit for state employees would be a great improvement for Kentucky’s civil servants, and the 2025 General Assembly should bring such a proposal forward and pass it into law. In the meantime, the executive branch could implement an identical program through existing statutory authority. Specifically, KRS 18A grants the secretary of the Personnel Cabinet the authority to establish regulations including for applications, incentive programs, layoffs, hours of work, comp time and various kinds of leave, including “special leaves of absence,” and paid parental leave could be implemented as a particular form of this leave.40

- Mary Elizabeth Bailey, “Annual Report 2022-2023,” Kentucky Personnel Cabinet, 2024, https://extranet.personnel.ky.gov/Annual%20Reports/2022-2023%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

- Dustin Pugel and Pam Thomas, “A Decade Without Raises and Weakened Benefits Have Created a State Workforce Crisis. Addressing it Adequately Should Be a Top Priority in the New Budget,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 11, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-state-workforce-crisis-should-be-a-top-priority-in-2022-2024-budget/.

- Some of these leave programs, including that of Jefferson and Oldham County Schools as well as the City of Frankfort, are fully funded by the employer. Jonathan G. Lowe, email interview by author, Oct. 21, 2024. Richard Graviss, email interview by author, Oct. 21, 2024. Kim White, email interview by author, Oct. 21, 2024.

- Northern Kentucky University Policy Administration, “Parental Leave,” ADM-PARENTLEAVE.

Bellarmine University Employee Handbook, “Parental Leave” and “Adoptive Leave,” pg. 50-51, https://www.bellarmine.edu/docs/default-source/hr-docs/employee-handbook.pdf?sfvrsn=8. University of Louisville Official University Administrative Policy, “Parental Leave,” PER-4.18, https://louisville.edu/policies/policies-and-procedures/pageholder/pol-parental-leave. - Lauren Franzen, email interview by author, Oct. 2, 2024.

- Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government Code of Ordinances, Sec. 21-37.3 — Leave of absence (Paid Parental Leave), https://www.lexingtonky.gov/paid-parental-leave-ppl#:~:text=LFUCG%20provides%20full%2Dtime%20and,such%20birth%2C%20adoption%20or%20placement.

Alana Morton, email interview by author, Sep. 30, 2024. - City of Frankfort Code of Ordinances, Ordinance No. 16, 2023 Series, “37.22 Paid Parental Leave,” https://www.frankfort.ky.gov/DocumentCenter/View/4195/Ordinance-No-16-2023-Series—Paid-Parental-Leave-Amendment#:~:text=%C2%A737.22%20PAID%20PARENTAL%20LEAVE,(3)%20of%20this%20Subsection.

- Louisville Metro Government Personnel Policies, “Paid Parental Leave,” 150.11, https://louisvilleky.gov/sites/default/files/2024-08/personnel_policies_082924.pdf.

- Norton Healthcare Employee Guide to 2024 Benefits, “Parental Leave Benefits,” pg. 22, https://nortonhealthcare.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2024-employee-benefits-guide.pdf.

UK HR Policies and Procedures, “Temporary Disability Leave,” HR Policy and Procedure #82, https://hr.uky.edu/policies/temporary-disability-leave. - Jefferson County Public Schools Policy Manual, “Paid Parental Leave,” 03.12331, https://policy.ksba.org/Chapter.aspx?distid=56.

Fayette County Public Online Manual, “Parental Leave for Childbirth or Adoption,” 03.1233, https://policy.ksba.org/Subscriber.aspx?distid=27.

Franklin County Online Manual, “Paid Parental Leave,” 03.1233, https://policy.ksba.org/Chapter.aspx?distid=32.

Oldham County Online Manual, “Parental Leave,” 03.2233, https://policy.ksba.org/Chapter.aspx?distid=252. - Humana Traditional associate benefits overview, “Parental leave (FT associate)”, pg. 13, https://docushare-web.apps.external.pioneer.humana.com/Marketing/docushare-app?file=4632199.

Ford 2024 New Hire Benefits Summary, “Family Building and Family-Friendly Programs: Support for New Parents,” pg. 9, https://corporate.ford.com/content/dam/corporate/us/en-us/documents/careers/2024-new-hire-benefit-summary-LL3-LL4.pdf.

Lexmark 2024 Benefits Handbook, “Paid Parental Leave,” pgs. 1-3. - Amazon employees are eligible if they have one year of continuous service and are regularly scheduled to work at least 30 hours per week before their child arrives. Amazon Employee Benefits: U.S. Benefits (Excluding Hawaii), “Family building benefits,” https://www.amazon.jobs/content/en/our-workplace/benefits-us.

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “State Family and Medical Leave Laws,” Aug. 21, 2024, https://www.ncsl.org/labor-and-employment/state-family-and-medical-leave-laws#:~:text=Mandatory%20Paid%20Family%20and%20Medical,family%20and%20medical%20leave%20programs.

- A Better Balance, “Map of Paid Parental & Family Caregiving Leave Policies for State Employees,” Mar. 15, 2024, https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/map-of-paid-parental-family-caregiving-leave-policies-for-state-employees/.

- While Ohio created its paid parental leave benefit for state employees in the 1990s, it just expanded the benefit by increasing the number of weeks a state employee can use in 2023.

- HB 179 24RS, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/recorddocuments/bill/24RS/hb179/bill.pdf.

- Mariam Khan, “Paid Family Leave and Children Health Outcomes in OECD Countries,” Children and Youth Services Review, September 2020, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740920306514?via%3Dihub.

Center for Law and Social Policy, “Paid Leave: A Crucial Support for Breastfeeding,” https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/files/Breastfeeding-Paid-Leave.pdf.

Shirlee Lichtman-Sadot and Neryvia Pillay Bell, “Child Health in Elementary School Following California’s Paid Family Leave Program,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Jul. 25, 2017, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.22012.

- Ariel Marek Pihl, “Did California Paid Family Leave Impact Infant Health,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Oct. 18, 2018, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.22101.

- Katherine A. Aherns et. al., “Paid Family Leave and Prevention of Acute Respiratory Infections in Young Infants,” JAMA Pediatrics, Aug. 26, 2024, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2822790#google_vignette.

- Natalie Brito et. al., “Paid Maternal Leave is Associated With Infant Brain Function at 3 Months of Age,” Child Development, Apr. 4, 2022, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35373346/.

- Karina Kozak, “Paid Maternal Leave is Associated With Better Language and Socioemotional Outcomes During Toddlerhood,” Infant, Mar. 23, 2021, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/infa.12399.

- Kathleen Romig and Kathleen Bryant, “A National Paid Leave Program Would Help Workers, Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Apr. 27, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/a-national-paid-leave-program-would-help-workers-families.

- Judy Jou et. al., “Paid Maternity Leave in the United States: Associations with Maternal and Infant Health,” Maternal and Child Health Journal, Nov. 2, 2017, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10995-017-2393-x.

- Aline Butikofer, Julie Riise and Megan Skira, “The Impact of Paid Maternity Leave on Maternal Health,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, February 2021, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20190022.

- Liliana Hidalgo-Padilla et. al., “Associations Between Maternity Leave Policies and Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review,” Archives of Women’s Mental Health, Jul. 17, 2023, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10491689/#CR12.

- Gillian Whitehouse et. al., “Leave Duration After Childbirth: Impacts on Maternal Mental Health, Parenting, and Couple Relationships in Australian Two-Parent Families,” Journal of Family Issues, Nov. 6, 2012, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0192513X12459014.

- National Partnership for Women & Families, ”Paid Leave Works: Evidence from State Programs,” Nov. 2023, https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/paid-leave-works-evidence-from-state-programs.pdf.

- Eyal Abraham et. al., “Father’s Brain is Sensitive to Childcare Experiences,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, May 1, 2014, https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.1402569111.

Madelon Riem et. al., “A Soft Baby Carrier Intervention Enhances Amygdala Responses to Infant Crying in Fathers: A Randomized Control Trial,” Psychoneuroendocrinology, October 2021, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306453021002547.

- Sakiko Tanaka and Jane Waldfogel, “Effects of Parental Leave and Work Hours on Fathers’ Involvement With Their Babies: Evidence From the Millienium Cohort Study,” Community, Work & Family, Nov. 7, 2007, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13668800701575069.

- Maria Del Carmen Huerta et. al., “Fathers’ Leave, Fathers’ Involvement and Child Development: Are They Related?” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, Jan. 13, 2014, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/fathers-leave-fathers-involvement-and-child-development_5k4dlw9w6czq-en.

- Julia M Goodman, Connor Williams, and William H Dow, “Racial/Ethnic Inequities in Paid Parental Leave Access,” Health Equity, Oct. 13, 2021, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8665807/.

- Julia M Goodman, Dawn Richardson and William Dow, “Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Paid Family and Medical Leave: United States, 2011 and 2017-2018,” American Journal of Public Health, Jun. 21, 2022, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306825.

- National Partnership for Women and Families, “Paid Family and Medical Leave Is Good for Business,” October 2023, https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/paid-leave-good-for-business.pdf.

Heather Boushey and Sarah Jane Glynn, “There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees,” Center for American Progress, Nov. 16, 2012, https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/08/CostofTurnover0815.pdf.

- Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher J. Ruhm and Jane Waldfogel, “The Effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on Mothers’ Leave-Taking and Subsequent Labor Market Outcomes,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Dec. 17, 2012, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.21676.

- Charles Baum II and Christopher J. Ruhm, “The Effects of Paid Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Feb. 2, 2016, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.21894.

- Lexington Urban County Council General Government and Planning Committee meeting, Sep. 10, 2024, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1lGy7Zma5Ef0tbqawAuB93hPwxa62HtGN/view?mc_cid=33a0e6af8f&mc_eid=bf5625796d.

- Kentucky Public Pension Authority, “Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the Fiscal Year That Ended June 30 2023,” Dec. 6, 2023, https://www.kyret.ky.gov/Publications/Books/2023%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

- SB 142 24RS, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/24rs/sb142.html.

- Mona Chalabi, “How Long Most Parents Wait Between Children,” FiveThrityEight, Sep. 9, 2014, https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/how-long-most-parents-wait-between-children/.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes (KRS) 18A.110, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=53726.