Kentucky parents with kids in child care are cutting back on essential family needs delaying major purchases, going into debt, switching jobs to accommodate child care, dipping into savings and even putting off having additional children to afford child care tuition, according to an expansive new survey conducted this month. These findings illustrate what many Kentucky families endure to afford child care and underscore the need for substantial state action to ensure families don’t lose care upon the expiration of federal pandemic funds that have provided critical support.1

Whitney, a parent from McCracken County, put it this way: “We will struggle to cut [household] budgets elsewhere to make up for childcare cost. We have to keep our child in a reliable, trustworthy childcare center to know she is taken care of while we work to provide for our family.”

Kentucky parents responding to the survey repeatedly shared the essential role of affordable, high-quality child care for their economic stability, job participation and overall quality of life. Access to affordable care is threatened by the looming expiration of federal funds that have helped to keep the child care sector afloat for the past four years. Without state action, families face an even more difficult child care landscape.2 There is a clear need among Kentucky parents for lawmakers to expand public support for child care and recognize the value of care for healthy communities and a robust middle class.

Who completed the survey?

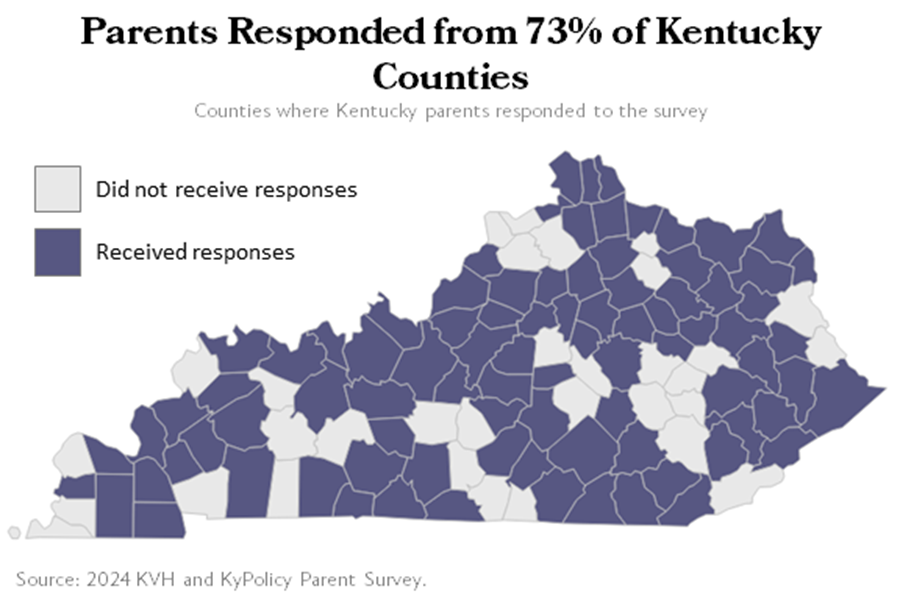

A total of 1,357 Kentucky parents with kids in child care responded to the survey between March 4 and March 12, 2024. The survey asked a broad range of questions to understand how much parents are paying for child care, what those costs mean for their finances and life choices, the availability of child care spots near their families, and what concerns they have should they lose child care. Responding parents have children of all ages in child care: 732 parents have toddlers, 553 have preschoolers, 351 have school-age children, and 256 have infants. Families responding to the survey have an average household size of 3.8 members, and live in 88 Kentucky counties.

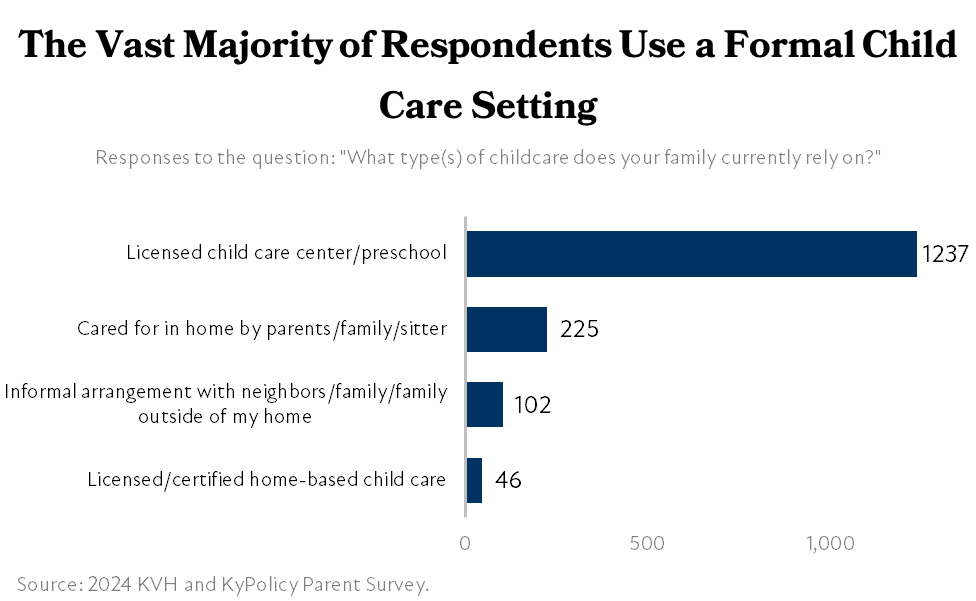

Responding parents utilize a variety of types of child care. While the vast majority use a licensed child care center or preschool, many respondents use a combination of settings that include both paid and unpaid care, such as informal arrangements with neighbors or family.

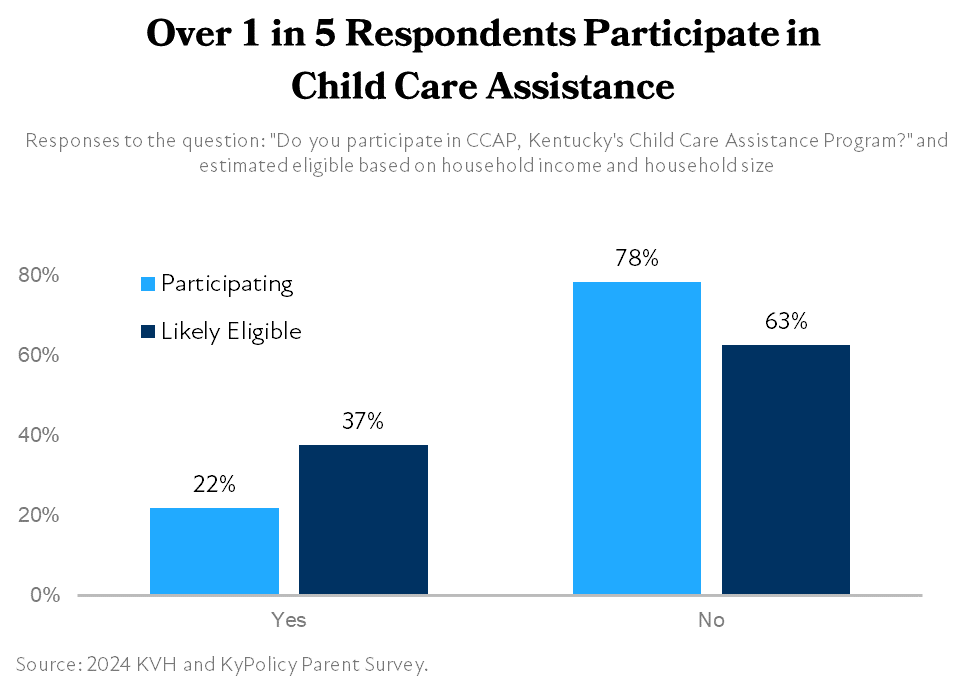

Roughly 21% of respondents receive help affording child care through the state’s Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP). Parents responded from across the income spectrum, with the majority of respondents earning below $100,000 as a household. Few responding parents come from households earning above $200,000 (7.4%) or below $15,000 (4.7%).

Families are spending a lot for child care and expect to pay more soon

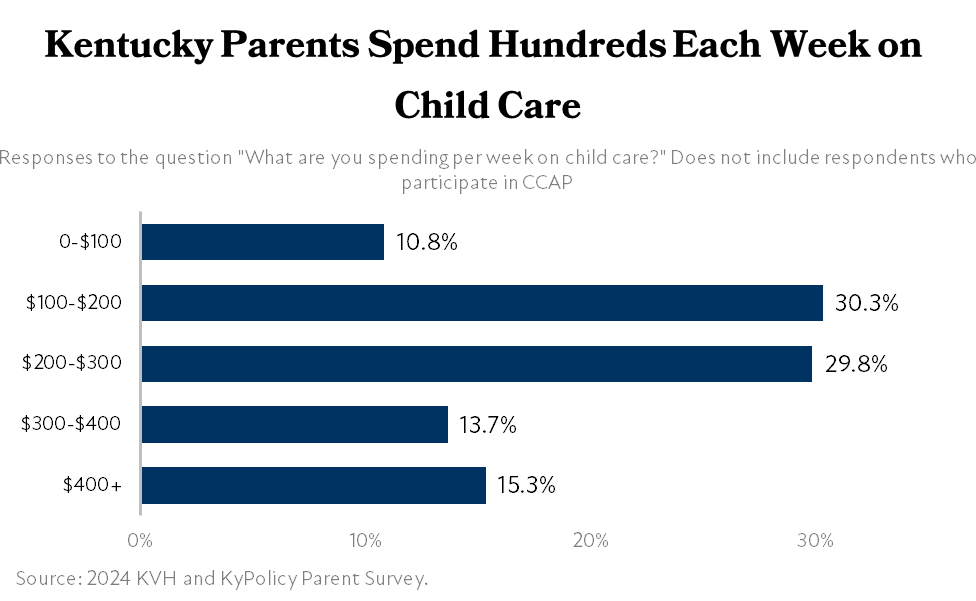

Already, over half of U.S. families spend more than 20% of their household income or more on child care.3 For Kentucky parents who responded to the survey, most paid hundreds of dollars per week. Among the 1,062 respondents who are private pay and do not participate in CCAP, 60% pay $100-$300 per week in child care, and 29% pay $300 or more.

One father from Daviess County illustrated the high cost of child care this way: “Childcare cost alone takes $13,000 out of my $32,000 salary. Luckly, I live in a dual income house but if rates continue to go up it will be cheaper for me just to stay at home.”

Another parent from Nelson County said, “Besides rent, childcare is my next highest bill coming in at $660 a month. This is a basic need to be able to continue to work and pay our living expenses.”

A Fayette County parent said simply, “Childcare is 60% of my paycheck, more than our rent.”

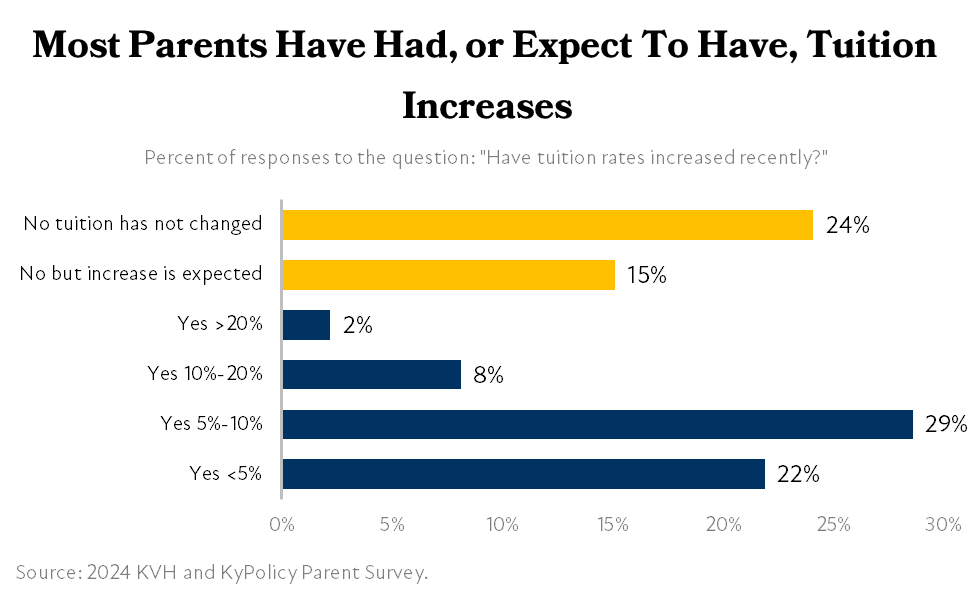

While tuition is already unaffordable for many parents, 61% of survey respondents have also experienced tuition increases recently, and an additional 15% expect tuition to rise soon. A Boyle County parent said, “When you are working a minimum wage job and child care has gone up over 20%, there is no way that you can make ends meet so the only other option is to quit your job.”

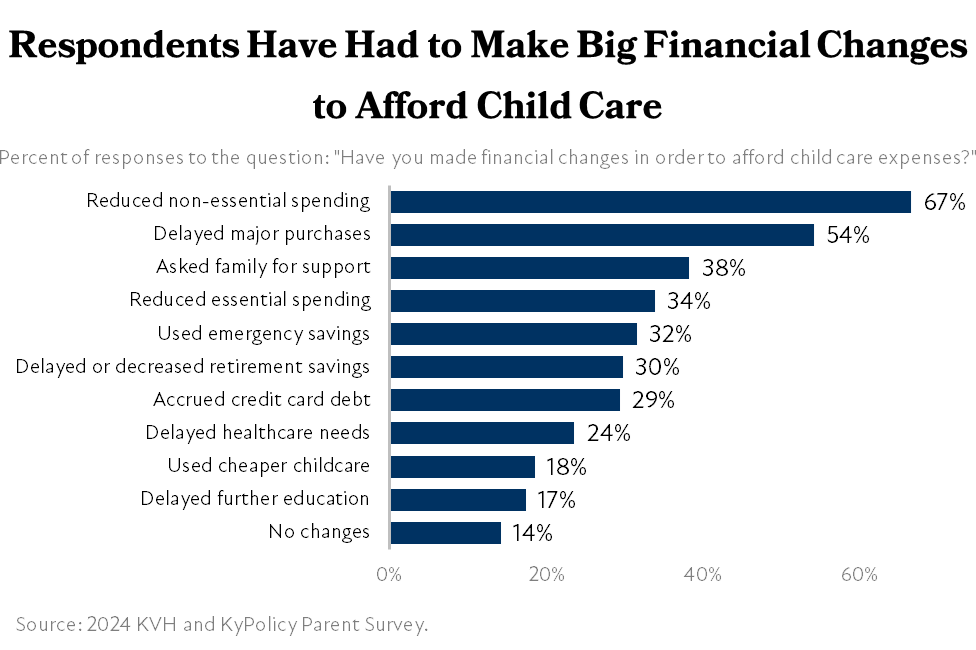

Spending so much on child care has forced very difficult choices for families

The fact that child care takes up such a significant portion of family budgets means parents are making significant financial decisions based on that cost. While two-thirds of respondents reported reducing non-essential spending to afford child care, 54% reported delaying major purchases (such as a house or car), 38% reported asking family for financial support, 34% reduced essential spending, 32% used emergency savings, 29% accrued credit card debt, 30% delayed or decreased retirement savings, and 24% delayed healthcare needs. Only 14% said they made no financial changes to afford child care.

An Oldham County parent reported that: “We can’t even afford current tuition rate. Currently using savings and credit card to pay for child care until one ages out.”

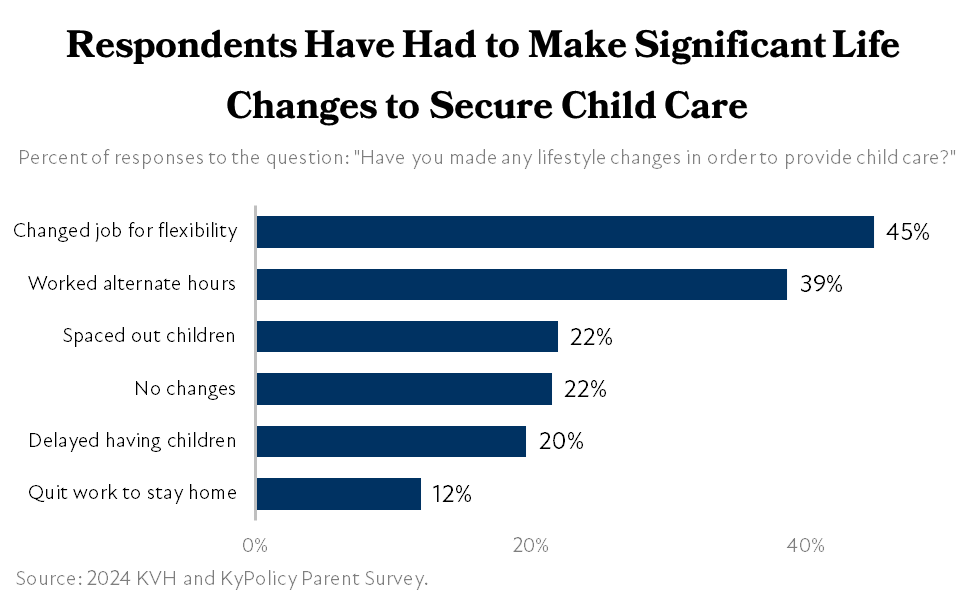

The burden of child care costs extends even beyond financial considerations and is forcing major career and life decisions. For example, 45% of respondents said they have changed jobs to gain flexibility related to child care, 39% altered their work hours, 22% waited longer to have additional children than they would have otherwise, 20% delayed having children altogether, and 12% left the workforce to stay home and care for their children. Just 20% reported needing to make no changes to afford child care.

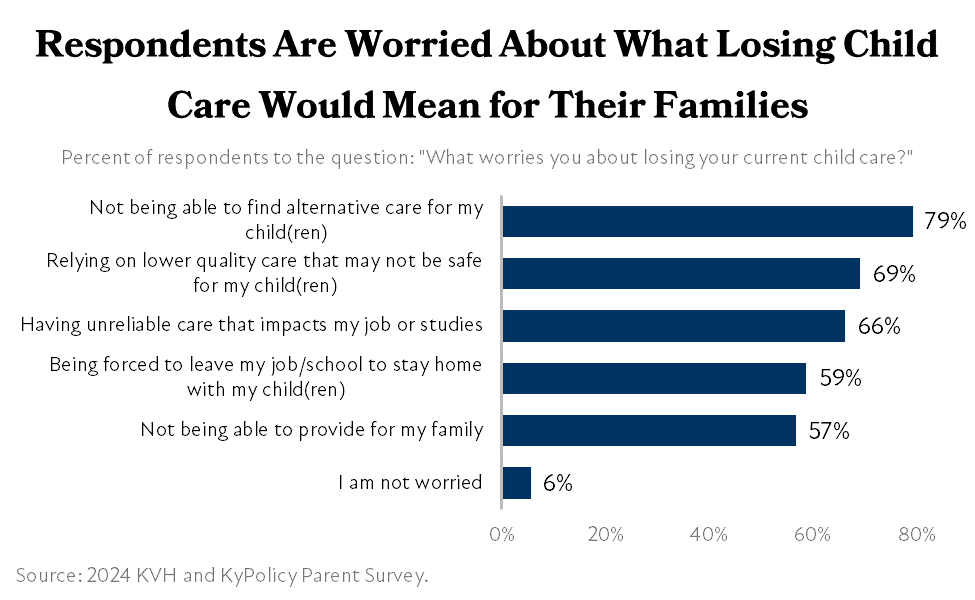

Parents are worried about their child care arrangements

High tuition, sparse options and inconsistent quality have led many parents to worry about their child care arrangements, and what might happen if they are lost. Respondents are concerned that if they lose their child care they won’t be able to find alternative care arrangements (79%), may have to use less safe care for their children (69%), would have unreliable care that impacts their job or education (66%), would be forced to leave their job or schooling to stay home with their children (59%), or wouldn’t be able to provide for their family (57%). Just 6% reported not being worried at all.

When asked what a lack of child care would mean for her family or job, one Fayette County mom said, “I can’t imagine. Both of us have to work to afford to live, so if we couldn’t work to care for our children, we would be in serious financial danger.” Another mom from Jefferson County said, “Families want to work but worry for our kids and worry we will be fired.”

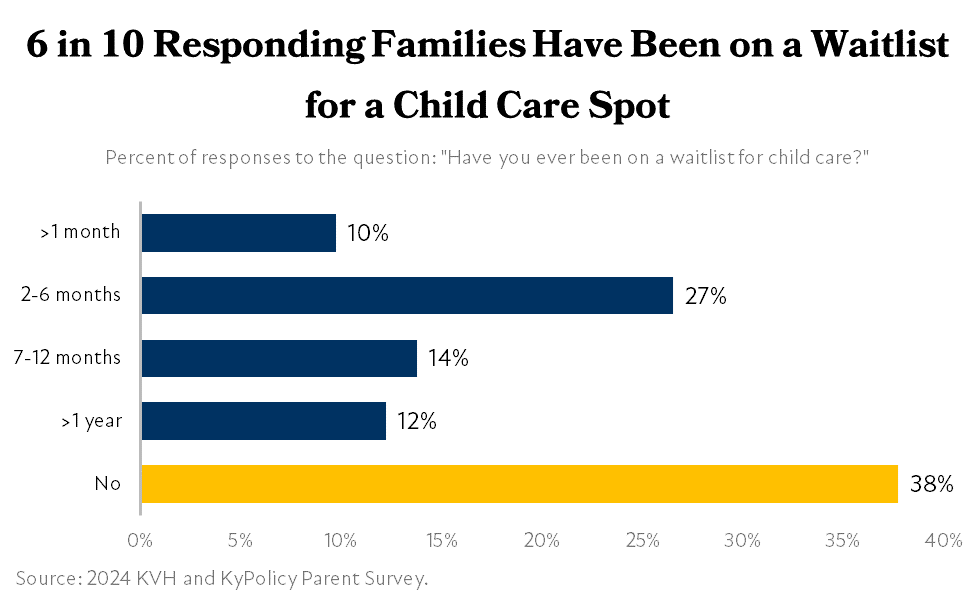

Limited child care options lead to waitlists for most, and more travel time for some

Finding an available child care spot is difficult in Kentucky, leading to long waitlists for families. There are 162,732 child care spots in Kentucky, but there are 265,100 children age 0-4 years old.4

This shortage of child care spots has led to 62% of responding parents having been on a waitlist for child care at some point. Of those who have been on a waitlist, 27% had to wait for 2-6 months, 14% had to wait for 7-12 months, and 12% had to wait for more than a year before a spot opened up.

A Henderson County parent reflected on her experience trying to secure a child care spot: “Affordable, high quality child care is so critical for families with working parents. It is far too often overlooked. And it is scary as a parent to be put on a wait list (personally I was put on five waitlists when I was four months pregnant with my oldest child) as it creates uncertainty and worry. If childcare is not affordable, families may be forced to put their children in questionable care situations because there is no other option.”

Sierra from Johnson County described waitlists so lengthy that they are unable to secure child care before their children enter grade school: “I need more accessible childcare. I have been on waitlist for 3 years now. The average for my area is 3-5 years. Children are aging out of preschool before getting into daycare.”

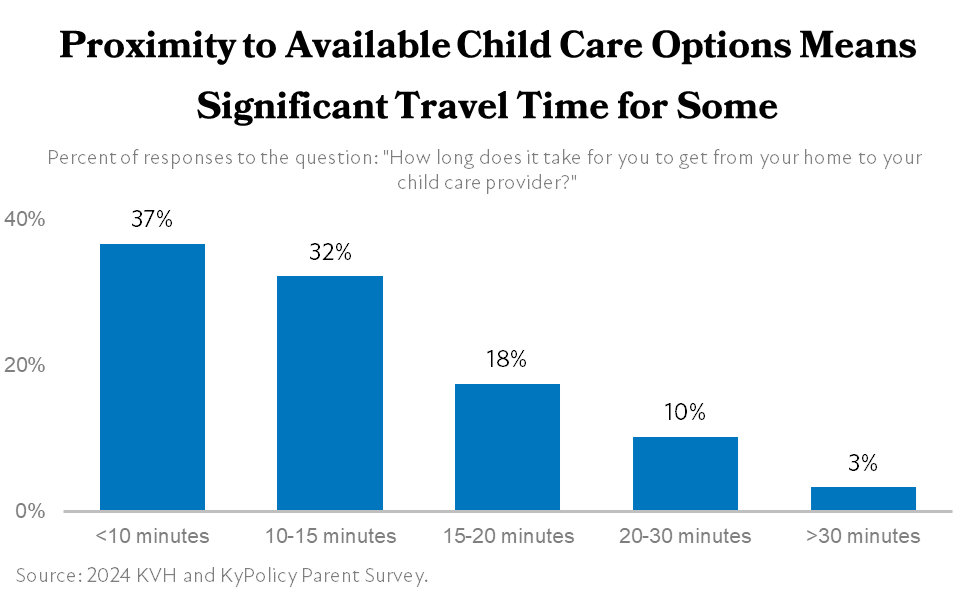

While 69% of respondents spend no more than 15 minutes driving to their child care provider, nearly 18% of respondents must travel 15-20 minutes each way and 10% travel 20-30 minutes.

One parent from Calloway County with a particularly long commute to and from their child care provider shared how a lack of options nearby leads to this problem: “We currently drive 100 miles round trip to access quality childcare. The lack of quality childcare in this area has our family contemplating moving to ensure our children receive the care and education that is standard in so many other parts of the country.”

Many families eligible for child care assistance are not participating, even with kids in child care

CCAP is one key tool the state has to provide families with help affording child care. As of 2023, nearly 35,000 Kentucky kids were in child care through this program, accounting for approximately 21% of total child care spots across the state.5 Among respondents to this survey, 22% reported participating in CCAP. However, 37% of respondents reported a household size and income that may qualify them for the program under the current income eligibility limit of 85% of State Median Income.

Current state funding levels are not sufficient to sustain the recent increases in CCAP eligibility and reimbursements to child care centers, let alone a large increase. But the respondents to this survey suggest that there are likely many more Kentucky families who are eligible for CCAP than are able to use it. This discrepancy could exist for many reasons, including that there are not enough centers nearby who offer care for families with CCAP, or that the options available are not high quality enough to draw potential CCAP-eligible families. In any case, it points to the need for more funding to ensure every family who could benefit from CCAP, can benefit from CCAP.

Kentucky’s youngest children and their families need public support

Parents in Kentucky are acutely aware of the crucial role child care plays in their families’ stability and well-being. Without access to or the ability to afford child care many responding parents feel they would have to leave their jobs, adding to already significant financial hardships. There is also a deep concern about the long-term impact of threatened access to child care on career prospects and quality of life. Worries over losing a job due to child care issues seemed to hit women particularly hard, as many commenters indicated that a mother leaving her job was the most likely outcome of losing child care. Already, mothers of young children have a much lower workforce participation rate (65%) compared to fathers of young children (93%) in Kentucky.6

Parents are also worried about their kids’ educational and social development, and the safety of their children if they are forced into using lower-cost, lower-quality care. The struggle to balance work and family life without child care support could have lasting affects on both parents’ careers and kids’ futures.

Kentucky is in a position to provide that support, however, and it must do so to stave off the worst impacts of the coming fiscal cliff left by expiring federal child care funding. As lawmakers weigh new investments in Kentucky’s child care sector and CCAP, they should consider what it means not just for child care providers, but the families they serve.

Without substantial new investments, thousands of families and their children will lose CCAP eligibility as the income eligibility threshold reverts to its lower, pre-pandemic level. Child care providers that care for children covered by CCAP will see their reimbursements plummet as supplemental payments expire. Employees of child care centers currently receiving CCAP for child care workers through a special program will no longer be able to keep their children in care at the centers they work for when that funding ends, likely leading more of those workers to seek employment elsewhere.

As child care centers receive a financial blow by the end of these federal funds, parents will be even more burdened when it comes to accessing and affording care. But funding affordable, plentiful and high quality child care is a responsibility we can and should all share.

- Dustin Pugel, “Kentucky Child Care Faces a $330 Million Fiscal Cliff, the General Assembly Can Help,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 25, 2024, https://kypolicy.org/child-care-funding-2024-2026-budget/.

- Emily Beauregard and Dustin Pugel, “Care at the Cliff: Kentucky’s Child Care Providers Plan Tuition Hikes, Wage Cuts and Closures Unless State Steps In With Substantial Investment,” Kentucky Voices for Health and Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 31, 2024, https://kypolicy.org/care-at-the-cliff-kentuckys-child-care-providers-plan-tuition-hikes-wage-cuts-and-closures-unless-state-steps-in-with-substantial-investment/.

- Lucy Danley, “Over Half of Families are Spending More Than 20% of Income on Child Care,” First Five Years Fund, June 29, 2022, https://www.ffyf.org/resources/2022/06/over-half-of-families-are-spending-more-than-20-on-child-care/.

- “Early Childhood Profile,” Kentucky Center for Statistics, August 2023, https://kystats.ky.gov/Latest/ECP.

“Kids Count Data Center,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, accessed March 15, 2024, https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/6429-child-population-estimates-by-age-group#detailed/2/any/false/2048,574,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868/174,155/13332. - KyPolicy analysis of data from an open records request to the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services received Jan. 30, 2024, and data from the KyStats “Early Childhood Profile,” accessed March 15, 2024.

- Samantha Evans, et. al. “The Economic Impact of Child Care by State,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://www.stlouisfed.org/community-development/child-care-economic-impact.