On the 154th anniversary of the abolition of slavery, barriers to thriving for black Kentuckians are still deeply entrenched. Data on wages and unemployment in Kentucky show that discrimination and systemic racism still hold us back as a state.

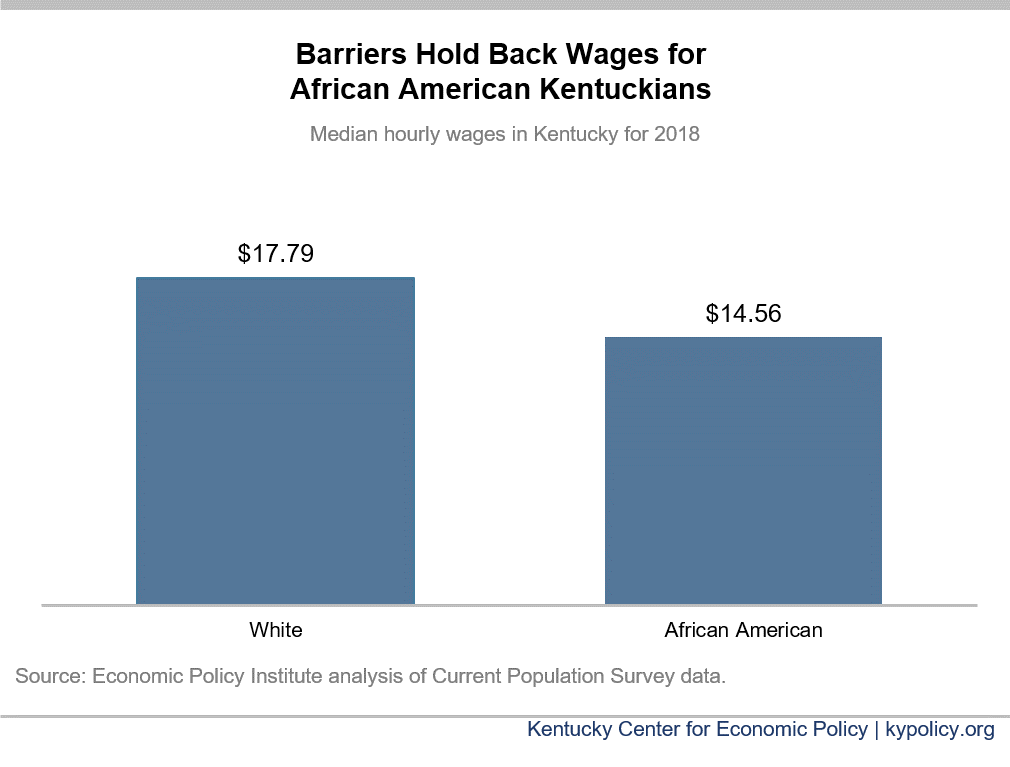

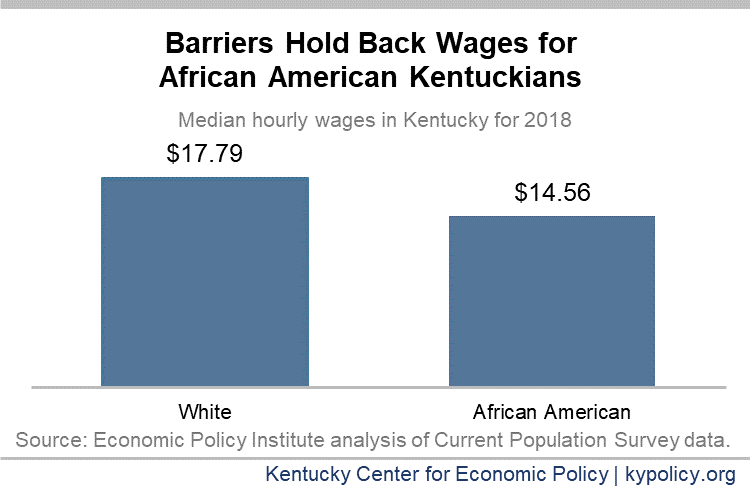

In 2018, the median hourly wage for black Kentuckians was 18.2% less than white Kentuckians and 14.8% less than the overall median wage — 81 cents on the dollar compared to white Kentuckians’ wages.

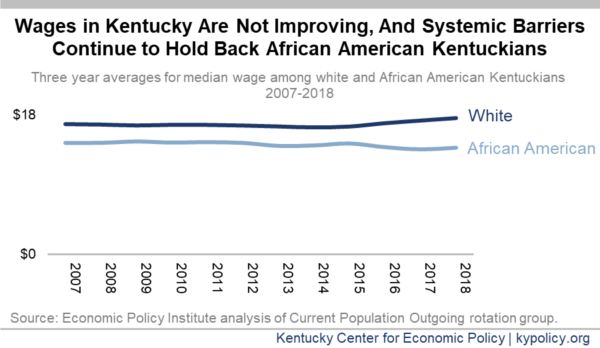

This is not a new problem, nor is it getting better. While the median wage has been stagnant for all demographics over the past decade, the difference between white and black pay has not narrowed and may have even widened in recent years.

Discrimination plays a large role in the race wage gap in Kentucky. The systemic barriers people of color face are the product of a long history of institutionalized practices that advantage white people. Though slavery has been abolished for over 150 years, Jim Crow laws, racial redlining and segregation in both education (at all levels) and the labor market all established an inequality of economic opportunity and barriers to advancement that persist, even though many of the most overtly racist policies have been put to an end.

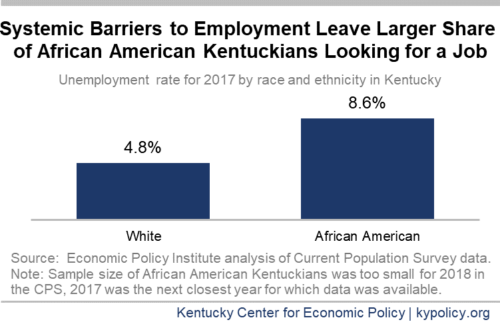

These same race-based barriers to economic opportunity also result in a higher unemployment rate for African American Kentuckians than for white Kentuckians, at 8.6 percent compared to 4.8 percent respectively. In other words, a larger share of black Kentuckians are actively looking for a job than white Kentuckians.

In America, children born of wealthy parents are likely to be wealthy when they become adults, and children born to poor parents are likely to be poor when they are adults. When race and class are considered together, the results are even more stark. Black boys are particularly susceptible to either remaining in low-income households later in life, or even becoming poor after being born into a wealthy family. The relatively high likelihood of being incarcerated that black men face – based on a discriminatory criminal justice system – is understood as a main contributing factor. Incarceration is an economic catastrophe for anyone, and black Kentuckians are disproportionately harmed, as state data shows.

Barriers to economic equality for black Kentuckians have developed historically and policy changes are necessary to remove them. Increasing the minimum wage; making childcare, housing and higher education more affordable; enacting criminal and juvenile justice reform and ending tax inequities that favor affluent white people are some of the many paths forward needed to ensure all Kentuckians have the opportunity to thrive.