One concern being raised in Frankfort about the existing defined benefit pension plan is that if the retirement system does not meet its expected rate of return of 7.75 percent per year, the cost to the state goes up. This concern is usually expressed by those who favor moving to a cash balance or defined contribution plan for new employees.

But a 7.75 percent return is in fact a reasonable assumption given historic performance and the realities of the market today, as explained by economist Dean Baker in recent testimony to the New Mexico legislature.

Baker notes that the stock market is inherently volatile, but that pension funds’ ability to meet their obligations is determined by the long-run rate of return, not the return in any particular year. A few bad years, or even a bad decade, do not sink a pension plan. A weak period is often followed by a strong period.

He notes that it is “nearly impossible that returns over the full projection period will fall substantially below the 7.75 percent return assumed by the state’s pension funds.” He says “there is very little downside risk to this projection,” calling 7.75 percent “a modest assumption.”

It should be noted that Baker gained a reputation as one of the few experts who accurately argued that the stock market was in a bubble in the late 1990s, and that there was an unsustainable bubble in the housing market in the 2000s. He is far from being a market optimist.

Baker explains that the key issue is return on equities, which either directly or through equity or venture funds make up about 70 percent of a pension fund’s assets. Baker notes that the historic rate of return for equities is over 10 percent. Assuming that the remaining 30 percent of the portfolio earns a return of about 3 percent, the total return would exceed 7.75 percent.

A key indicator in determining whether that rate of return on equities is likely, Baker notes, is the price-to-earnings ratio for stocks. When it is inflated, as it was during the two market bubbles of the 2000s, it would be wrong to assume strong returns in the future. But now that it is back down to normal levels, it is reasonable to assume historic rates of return moving forward.

Baker details how using reasonable assumptions for economic growth, corporate profits, inflation and dividend yields makes achieving a long-term rate of return for stocks of 9.5 percent quite plausible. In fact, he argues, it would be very difficult to construct a scenario with a much lower rate.

Historic experience in Kentucky is in line with Baker’s analysis. The Kentucky Retirement System’s overall rate of return for its pension fund since inception is much better than 7.75 at 9.36 percent.

Overheated concerns about the pension system’s ability to achieve its long-term investment targets are being used to promote changes that would cut benefits for many workers and shift risks to them. But we need to make decisions about these important issues based on a hard-eyed look at the facts and the experience.

ADDENDUM

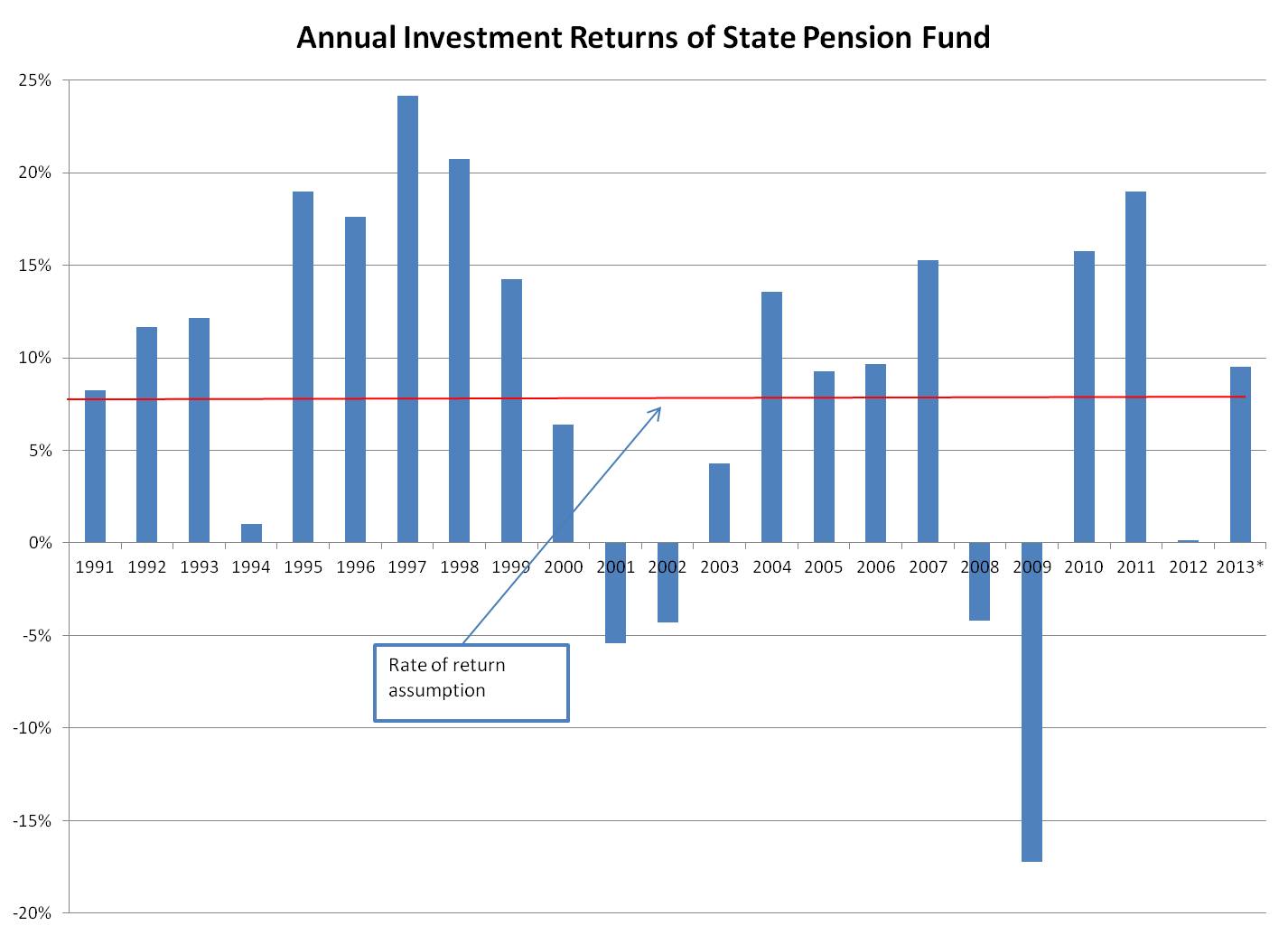

Here’s another look at the historic investment performance of Kentucky Retirement Systems. Since 1991, the KRS pension fund has exceeded the long-run rate of return of 7.75 percent in 14 of 22 years, and it’s on track to exceed the benchmark in 2013. While losses in the recessions of 2001-2002 and 2008-2009 were certainly painful, they don’t define the system’s investment history.

Source: KCEP analysis of Kentucky Retirement Systems data provided to Task Force on Kentucky Public Pensions. 2013 returns are for the first seven months of the year (through January).