Many Kentucky communities still face deep economic challenges eight years into the recovery from the Great Recession, and yet the state plans to make Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits for thousands of Kentucky adults conditional on meeting work requirements after three months. Since jobs are still hard to find in significant parts of the state, this change will result in loss of food assistance and harm to economic activity in already-struggling local communities.

SNAP benefits are modest, but important to a broad range of Kentuckians

As of November 2017, 640,636 Kentuckians received SNAP, which is the lowest SNAP enrollment since July of 2008. The average benefit for SNAP is only $1.36 per person, per meal and is meant to cover just a portion of the cost of a family’s food budget. As of 2015, the most recent year for which detailed participant data was available, a broad array of Kentuckians were able to use SNAP, including:

- 313,000 children.

- 101,000 disabled adults.

- 98,000 single parent households.

- 87,000 non-disabled adults without dependents.

- 66,000 Kentuckians over 60.

Non-disabled adults without dependents are the Kentuckians who are at risk of losing SNAP benefits by Kentucky putting in place time limits.

Kentucky to reinstate time limit in all but eight counties, some for the first time

During the Great Recession and subsequent slow recovery, the three-month time limit on SNAP benefits for childless, non-disabled adults working less than 20 hours per week was waived in all 120 counties in Kentucky, as it was for the rest of the country. Beginning in 2016, state administrators began to allow waivers in counties with low unemployment rates to lapse. This ending of waivers began with a group of 8 counties and increased to 20 by the end of 2017. The remaining 92 counties (8 in southeast Kentucky will remain exempt) will expire on a month-to-month schedule through May:

- 28 in February

- 15 in March

- 22 in April

- 27 in May

By May, most of the 87,000 Kentucky adults without dependents will have to prove to the state that they work or engage in some kind of work activity such as school, voluntary employment and training programs provided by the state or workfare (a kind of unpaid internship, often with nonprofits). If they have not kept up 20 hours of work activities per week for more than three months at any point in the past three years they will become ineligible for SNAP benefits – a rule that has never been in effect for all of Kentucky since the time limit went into effect in 1998. In fact in most of the years since 1998, a large number of Kentucky counties have been under a waiver due to a persistent lack of jobs.

Allowing waivers to expire will likely result in fewer people with food assistance

When Kansas allowed its waivers to expire in October of 2013, total SNAP enrollment dropped by 15,000 people the following January (three months after expiration). The total number of Kansans on SNAP had already been in decline as an improving economy made people’s incomes rise above the eligibility threshold, but January’s decline was four to five times faster than it had been in previous months. Oklahoma experienced a similar decline when it reimposed SNAP time limits in 2014. Although many factors play into this caseload decline, it is likely Kentucky will also see many people lose SNAP in the months following each phase-in of the time limit.

Reinstating the three-month time limit will be especially difficult for groups of Kentuckians facing special barriers. Racial and ethnic minority Kentuckians more likely to face discrimination in labor markets, Kentuckians lacking a high school degree or GED and those with criminal records all deal with added challenges to finding long-term employment with enough hours. This is especially true in rural parts of the state where job availability continues to shrink compared to urban parts of the state that have better recovered from the Great Recession. There are 77 rural Kentucky counties that have fewer jobs now than 10 years ago, and 23 of those counties have seen a greater than 20 percent drop in jobs.

Time limit waivers are designed to alleviate pressure on economically distressed communities

For areas where there are insufficient jobs, state authorities are allowed to ask the Department of Agriculture (USDA) for a waiver from the work requirement. As of 2017, 36.4 percent of the U.S. population lived in an area where the time-limit was waived, including every county in six states and broad swaths of four bordering states.

One of the main criteria used for whether a county qualifies for a waiver is if it has been designated a “Labor Surplus Area” by the Department of Labor, meaning there is more labor than available jobs. Currently in Kentucky, 47 counties and 3 cities are deemed Labor Surplus Areas, and therefore are “readily approvable” by the USDA, though more or all of Kentucky’s counties could potentially still be waived, as in the case in other states including New Mexico and Louisiana.

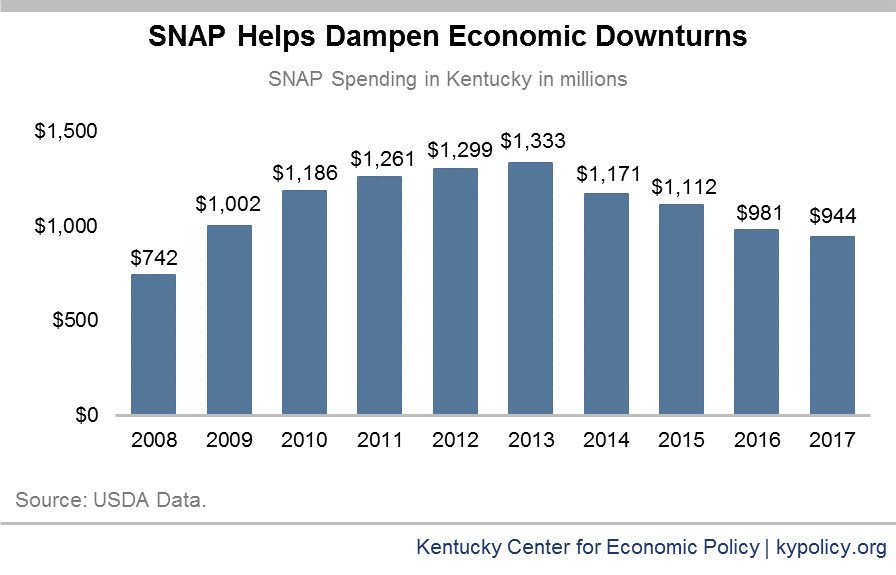

In addition to helping people make ends meet, waivers help local economies offset broader economic harms where layoffs and stagnant wages drag economies down. In 2013, when SNAP enrollment was at its highest, the program pumped over $1.3 billion into Kentucky grocery and convenience stores — with a multiplier of $1.70 in broader economic activity for every $1 spent through SNAP. This “countercyclical” effect helps to stimulate the economy when it is weak, preventing further job loss and economic decline as well as helping people make ends meet.

Work requirements are a step backwards

A comprehensive review of research shows that, for both SNAP and cash assistance through Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), work requirements:

- Don’t create stable, long-term employment,

- Don’t reduce poverty, and in some cases result in more people at or below 50 percent of poverty and

- Don’t increase the likelihood of finding employment.

A recent example is in Maine, where in October of 2014 the three-month time limit for non-disabled adults without children was reinstated. In the four quarters following the cutoff, work rates for these SNAP enrollees did not meaningfully change, and of those who were cut off SNAP, over half said they were still unsuccessfully looking for a job. Nationally, work rates among SNAP households have risen for decades, even while non-disabled adults without dependents were not required to work in order to keep benefits, including for households with at least one working age, non-disabled adult.

Although work requirements don’t achieve the goals proponents claim, they do result in fewer people receiving vital support to help make ends meet. As Kentucky’s waivers expire, most low-income adults won’t see their incomes rise or find jobs that offer more hours, but will see their food assistance terminated. Addressing poverty requires public investments in infrastructure and other areas that will create jobs and policies like raising the quality of jobs — not taking away supports that help people meet essential needs.