The proposed changes to the “public charge” rule by the President’s administration, published yesterday for public comment, are a radical change in immigration policy that would have harmful effects for immigrant families in Kentucky and across the country. Among the numerous troubling outcomes if this rule goes into effect is that it would keep many individuals and families from participating in a wide range of public programs for which they are legally eligible.

Changes Proposed to Public Charge Rule

When a person requests to enter the U.S., or when immigrants already in the country apply to have their status changed (such as those seeking Lawful Permanent Resident status) or extended, federal authorities take certain factors into consideration to determine whether they are a “public charge,” a status that often results in a denial of immigration requests. The longstanding federal policy has been to deem a person a public charge if more than half of their income is from cash assistance (such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI)) or long-term institutional care funded by the government. The proposed changes to this determination would lead to many more people – specifically, immigrants with legal status, as undocumented immigrants are already ineligible for nearly all of these programs – being classified as public charges.

The proposed rule would make it more likely for individuals to receive a public charge determination in a number of ways. One significant change is that it expands the benefits included in public charge determinations to include additional key programs that help participants meet their basic needs: non-emergency Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicare Part D Low Income Subsidy (which reduces the cost of prescription drugs), and housing assistance such as public housing or Section 8 housing vouchers.

And unlike the current rule that penalizes financial reliance on several cash assistance programs at the time of application for more than half of total income, the proposed rule scrutinizes the receipt of all of previously listed public benefit programs in the prior 36 months, even if the benefits reflect only a small share of an immigrant’s total income. If an individual has received during this time period cash or cash-like assistance (“monetizable benefits”) in the amount of 15 percent of the poverty level for a single person (currently $1,821) in a 12-month period, it is weighted heavily against them. And for benefits with an undetermined value (“nonmonetizable benefits”) such as health insurance and public housing, the limit is 12 months in a 36-month period, or just 9 months if you receive both monetizable and nonmonetizable benefits (benefit receipt would be examined starting when the rule goes into effect, not retroactively prior to this time).

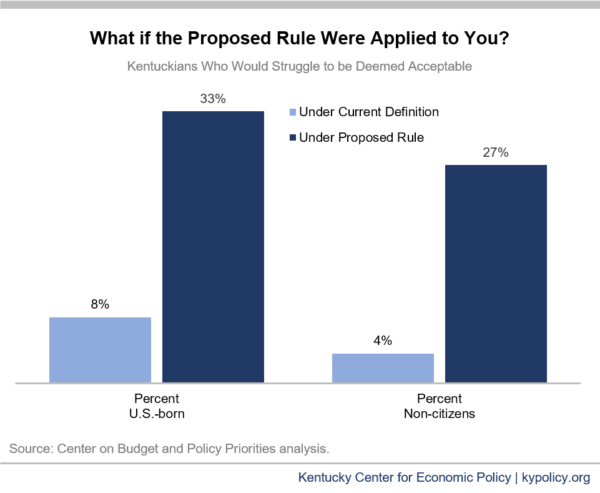

By statute the “totality of the circumstances” of an applicant’s ability to support themselves must already be taken into consideration in order to make a public charge determination. The proposed rule, which changes the way these factors are defined and weighted, would make it easier to be determined a public charge. For instance, having a high income is the only heavily weighted positive factor, while having a diagnosis of a medical condition which requires extensive treatment, having a low income and public benefit utilization are each heavily weighted negative factors. As seen in the table below, if the current public charge rule was applied to all Kentuckians, just 8 percent would fall into the “public charge” category, but under the proposed rule 33 percent of all Kentuckians would. For Kentuckians who are non-citizens (many of whom have legal status), just 4 percent would be deemed unacceptable under the current public charge rule but under the proposed rule 27 percent would be.

Rule Change Would Prevent Immigration and Worsen Poverty

Two main effects of the proposed rule would be to prevent some immigrants who are in the U.S. lawfully and who receive any of these benefits from becoming residents and to prevent prospective immigrants who want to reunite with their families from entering the U.S.; and to create new barriers to economic security and well-being. Out of fear that they could have immigration requests denied, a large number of immigrants in the U.S. lawfully would be likely to forgo benefits for which they’re legally eligible.

The latter impact is often called a “chilling effect”— and it has happened before. In the late 1990s, widespread confusion and fear about public charge rules led to fewer people utilizing programs for which they were eligible. Some immigrants, in response to the current proposed changes, are already starting to abandon public nutrition services out of fear of what is to come.

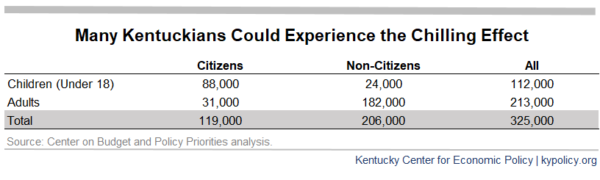

Given this fear and the fact that such rules and the determination process are so technical, the number of low-income immigrant families that would choose not to receive benefits would be considerably larger than the number that would actually be subject to a public charge. The “chilled population” are those who are likely to be nervous or confused about whether they should apply for benefits if they qualify (estimated in the table below to be everyone who lives in a family with at least one non-citizen immigrant, and where someone in that family has received one of the public benefits named in the public charge rule). As seen in the table below, several hundred thousand Kentuckians could experience such a chilling effect due to the proposed changes to the public charge rule.

Low-Income Families and Kentucky Economy Would Be Harmed

These changes would essentially restrict immigration to the wealthiest and most privileged applicants as people would generally fail the public charge test if they had income and resources of less than 250 percent of the federal poverty guidelines or a medical condition. In fact, it is estimated that the new criteria is so restrictive that a third of U.S.-born citizens would have trouble meeting it if they had to take it today.

The proposed rule would inevitably harm immigrant children and families, causing Kentuckians to make heart-wrenching decisions. As a parent, if you apply for SNAP or Medicaid, you may risk being able to stay in this country with your kids. Yet, not applying may mean seeing your family go hungry or not being able to see a doctor when you are sick. Some children will themselves be subject to the proposed rule. A far greater number live in families that will likely experience a chilling effect.

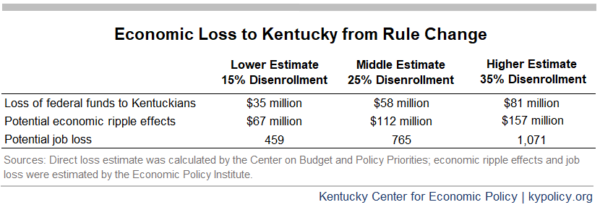

The rule would also have negative economic impacts. SNAP and other benefits circulate resources in our local economies (grocers, supermarkets, farmers markets, for instance) and have important positive effects on children and their ability to contribute to the economy as adults — impacts that would be depressed by the proposed rule change. And a likely significant increase in people who lack health insurance — and therefore who go to the emergency room for oftentimes uncompensated medical care instead of going to see a doctor — could harm the financial health and viability of some Kentucky hospitals and doctors’ offices. Some spending would also be reduced in other areas of the economy as families struggle to pay food and health costs. And when businesses have less revenue, they lay off workers.

The table below estimates the economic loss to Kentucky as a result of the rule change, according to three different scenarios of disenrollment in benefit programs we could expect to see based on the impact of past policy changes.

New Americans in Kentucky — of which more than one in three are naturalized citizens and the rest are legal residents and undocumented immigrants — and their children make important economic contributions to our state. They are well-represented across our workforce, particularly among small business owners. And whether native-born or foreign-born, when we remove barriers to Kentuckians’ economic security, our communities and local economies are better off. Yet thousands of Kentuckians – U.S. born, naturalized and non-citizens with or without legal status – could be harmed by the proposed public charge rule change.

The public comment period for the proposed rule ends Dec. 10; information on how to submit a formal comment can be found here.