The economy is growing, but job growth is happening way too slowly. To make matters worse, low wages keep many of those Kentucky workers with jobs from meeting their families’ basic needs.

In Kentucky, the big job losses since the beginning of the recession have been in middle-skill industries like manufacturing and construction that have historically meant middle-class wages for workers without a college education. Kentucky has lost a net 35,400 manufacturing jobs since December 2007 and 18,800 construction jobs.1

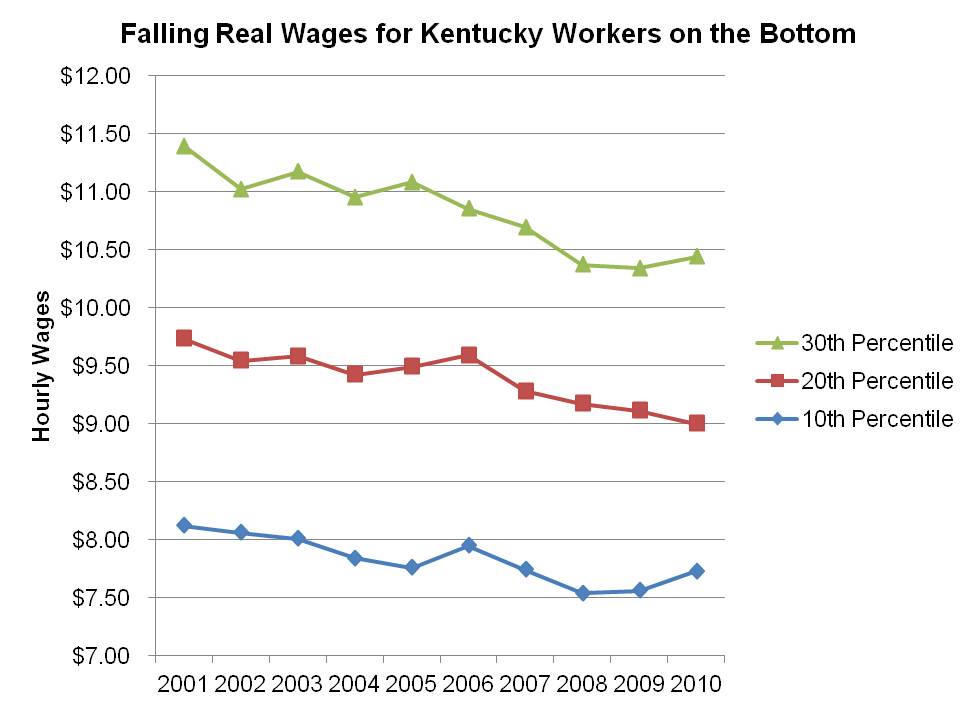

Decent jobs are going away, while wages at the low-paying jobs that are left have been flat or declining. The figure below shows Kentucky real wages at the 10th, 20th and 30th percentile over the last ten years (at the 10th percentile, 90 percent of workers make higher wages and 10 percent make lower wages). Since 2001, real wages have fallen 5 percent, 8 percent and 8 percent for workers at those three levels.

Source: Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey data provided by the Economic Policy Institute

Wages at the bottom are also simply too low. According to one study, income around 200 percent of the federal poverty line is needed for families in Kentucky to meet basic needs. Yet in Kentucky in 2010, 25 percent of jobs were in occupations that paid wages below the poverty level, while 75 percent were in occupations that paid wages below 200 percent of poverty.2 The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that the occupations with the most annual openings over the next ten years in Kentucky will be in the areas of office and administrative support, sales, food preparation and food service, and retail sales—all of which tend to pay low wages.

There are many causes of the problem of low wages, one of which is the real decline of the minimum wage. The federal government increased the minimum wage back in 2007, but at $7.25 an hour it is still too low. If the minimum wage had kept up with inflation over the last 40 years, it would be $10.55 an hour. Studies show increases in the minimum wage help not just those workers at the very bottom of the wage scale, but workers with wages somewhat above the minimum.

Unlike 18 other states, Kentucky does not require a minimum wage above the federal minimum, and the minimum wage for tipped workers in Kentucky is also at the federal minimum of only $2.13 an hour. Ohio provides a higher minimum wage and—like 10 other states–adjusts it annually to increases in inflation. Missouri put raising the minimum wage and indexing it to inflation on the ballot in 2006, and it was approved by 76 percent of Missouri voters.

Low wages harm not just those workers, but the economy as a whole. The biggest drag on employment and economic growth in the country is the lack of consumer spending, and a 2011 study by the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank found that every dollar increase in the minimum wage results in $2,800 in new consumer spending over the following year. If we take steps to bring wages up, we can help finally bring the whole economy back.