Others have rightly jumped on Nicholas Kristof’s December column in the New York Times criticizing the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program for children with disabilities. Kristof uses stories of families in Breathitt County, Kentucky, to suggest widespread abuse of the program, including cases where parents have kept their children from learning to read in order to maintain a monthly check.

Accusations of systematic abuse of SSI for children have arisen before, and the Government Accountability Office and other investigators have examined and discredited the claim. Getting SSI is in fact difficult, child participation in the program is not mushrooming and 98.6 percent of kids under age 12 in SSI are enrolled in school. SSI is a big help to families paying the extra costs associated with raising a child with disabilities, and a growing body of research shows that poor kids in families receiving an income boost tend to do better in school and work and to have higher earnings as adults.

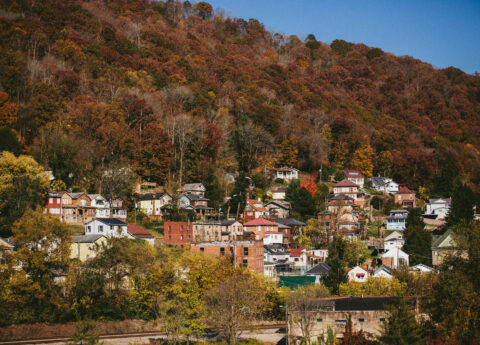

That’s not to say there are no specific instances of misuse or ways to improve the program. But even in Breathitt County, the Social Security Administration reports there were only 262 children on SSI in 2011 in a county with a 47 percent child poverty rate. The share of kids on SSI is substantially higher there than in the nation as a whole, but disbursements are hardly at a level that can be described, in Kristof’s words, as a “burden on taxpayers.”

More importantly, what would cutting this safety net program, as Kristof proposes, truly do to help address the bigger challenge of poverty in Breathitt County and Eastern Kentucky?

The problem with poverty diagnoses like Kristof’s is that they look narrowly at strategies to treat the poor themselves while ignoring the larger historical and economic context in which those families live. He doesn’t dig deeper to ask why there are so many hardships and so few jobs in a place like Eastern Kentucky.

Part of the answer to that difficult question, I believe, can be found in a recent book by economist Daron Acemoglu and political scientist James Robinson titled Why Nations Fail. The authors look across countries and throughout history to ask why some places are poor and some are rich. They conclude that economic success is not the result of culture, geography or other standard explanations. Rather, prosperity is caused by a country’s human-made institutions.

They characterize nations’ economic and political institutions as either inclusive or extractive. Inclusive institutions create a fair environment for competition, provide education and encourage innovation, distribute political power widely and encourage public participation, and have an accountable and responsive government. Extractive institutions are designed to benefit the few at the expense of the many. They discourage democratic participation, fail to enforce the rule of law or promote new economic activity, and are characterized by corruption and cronyism.

Whether a country has inclusive or extractive institutions is established historically, but no place is doomed. Small institutional changes interact with what the authors call critical junctures to set or change a country’s path. Inclusive economic and political institutions create virtuous circles whereby growing prosperity and a strengthening democracy reinforce each other. Extractive institutions create vicious circles that make it harder for things to change.

It’s easy to see how Acemoglu and Robinson’s theories could be applied to Breathitt County and to Eastern Kentucky more generally. The region has long been made up of haves and have-nots. In the late 19th century, wealthy investors and their powerful local allies bought up much of the region’s land and mineral rights. Coal and timber companies extracted the natural wealth while leaving behind little but damaged land. Company towns formed rather than vibrant local democracies. Small groups of local elites, closely linked to dominant industries, established “little kingdoms” in local government focused on enriching themselves and maintaining power.

Although Breathitt County is not now one of the region’s major coal producers, it has been part of eastern Kentucky’s coalfields throughout its history. Coal exemplifies the kinds of challenges Acemoglu and Robinson identify. Its dominance in the region politically, economically and physically has limited economic diversification. The rule of law and protection of private property, two attributes of inclusive institutions according to Why Nations Fail, often haven’t applied to coal. Laws to address the impacts of coal on land, water and worker safety have often been missing or simply unenforced. Just one example: In 2009 flooding along Quicksand and Cane Creeks, exacerbated by poor reclamation of surface mines in the area, destroyed hundreds of homes – in Breathitt County.

While in his column Kristof rightly talks about the importance of schools and of early childhood education in addressing poverty, he fails to mention that Breathitt County’s school system was recently taken over by the state due to corruption and mismanagement at the top. The superintendent was indicted for vote-buying; he is the eleventh county leader (including the sheriff) to have been recently convicted or pled guilty to illegal activity associated with political battles among county elites. The Lexington Herald-Leader noted that Breathitt County “is becoming almost a full-time job for the FBI and the U.S. Attorney.”

When we scratch our heads about poverty in America, we too often ask what’s wrong with poor people who are struggling to survive rather than what’s wrong with our politics and economy. Unfortunately, the conclusion to Why Nations Fail offers no simple solution for poor places. The authors emphasize that the solution is not micro-level changes to incentives or development efforts that just reinforce existing inequalities. The answer, they say, is broad-based empowerment — building a stronger and deeper democracy in those places.

Developing new leaders and organizations can foster inclusive political and economic institutions. That’s not easy. The process is slow, but it can be accelerated by unanticipated critical junctures that create opportunity. Is the current economic transition related to coal in Eastern Kentucky just such an opportunity? It’s hard to say. But building an economy by building a democracy may be just the approach our region needs.