PDF version: Lessons from the Great Recession: Kentucky and Other States Need More Federal Relief

As the nation faces the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critical that the federal government design a policy response that builds on lessons from the most recent downturn. Congress provided significant relief to states in 2009 that was essential to keeping the Great Recession from turning into a depression. But the aid was not large enough relative to the depth of the downturn, and it ran out before recovery was achieved. That withdrawal of support slowed the economy in part by hindering the ability of states like Kentucky to provide vital public services to families and communities.

While Congress has provided some state relief during the COVID-19 economic crisis, new forecasts show that the severity of the crisis means states and localities will need much more in aid as they face cratering tax revenues and rising public costs.

Federal aid to states prevented the Great Recession from turning into a depression

Aid to states is one of the most effective policy actions available to make recessions short and shallow. Unlike the federal government, states face balanced budget requirements, limiting their ability to address rising costs for programs like Medicaid amid falling state tax receipts. Without state fiscal relief, resulting budget cuts drag the economy down further. And since states provide many safety net and support services that are even more critical at times of high unemployment, state budget cuts increase the pain of recessions for people and communities.[1]

When the Great Recession hit in the late 2000s, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to stimulate economic growth. By injecting spending into an economy that was shrinking, ARRA was very effective at halting its collapse and keeping the recession from becoming a depression. The Congressional Budget Office and other analysts estimate that it created millions of jobs and gave a substantial boost just when the economy needed it.[2]

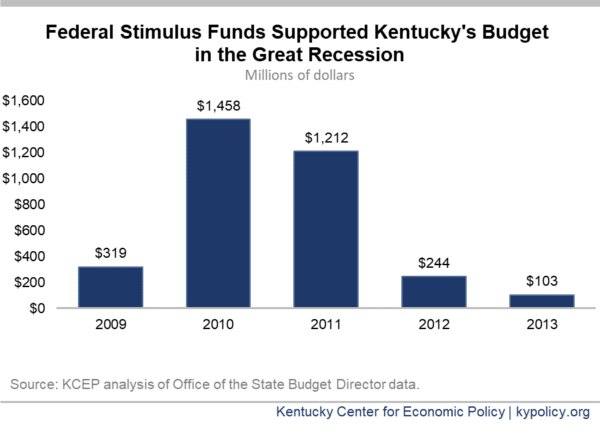

In the case of Kentucky, the federal government provided approximately $3.3 billion directly to the state’s budget (to put that in context, Kentucky’s General Fund budget was less than $9 billion a year at the time). Of the aid, $651 million was through the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund, which provided flexible grants to states to help weather the crisis. Another $2.7 billion was in other funding, including a significant increase in the federal share of Medicaid costs by 10 percentage points (from 70% to 80%).[3] A total of 80% of ARRA aid to Kentucky came in fiscal years 2010 and 2011, as shown in the graph below.

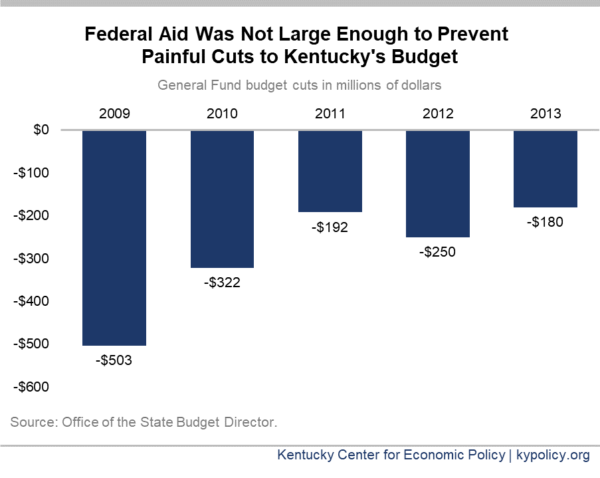

Depth of crisis meant Kentucky needed more in federal aid than was provided to prevent painful cuts

Despite substantial funds provided to states under ARRA, Kentucky was still forced to cut its budget due to the depth of the biggest recession since the Great Depression. The downturn caused a sharp decline in tax receipts and rising costs for programs like Medicaid, for which enrollment increased by approximately 100,000 people due to lost jobs and income. Even when ARRA relief was at its peak in 2010 and 2011, Kentucky cut $514 million in spending. Altogether from 2009 to 2013, the state cut an enormous $1.4 billion from its budget even with the ARRA aid the state was receiving. Those cuts translated into bigger K-12 class sizes, higher college tuition, strained social services and a lack of raises for public employees, among other impacts.[4]

The legislature also raised some modest new revenue on its own during this period to help cushion the blow. In 2009, the General Assembly raised over $150 million a year by enacting a tobacco tax increase and applying the sales tax to alcohol. Without the state revenue increase, budget cuts would have been even deeper.[5]

Federal aid dried up too soon, causing more cuts

The first graph above illustrates how federal aid from ARRA dropped dramatically beginning in 2012 before ending entirely in 2014. As the graph immediately above shows, that withdrawal of assistance resulted in prolonged pain, with Kentucky making additional budget cuts of $250 million in 2012 and $180 million in 2013.

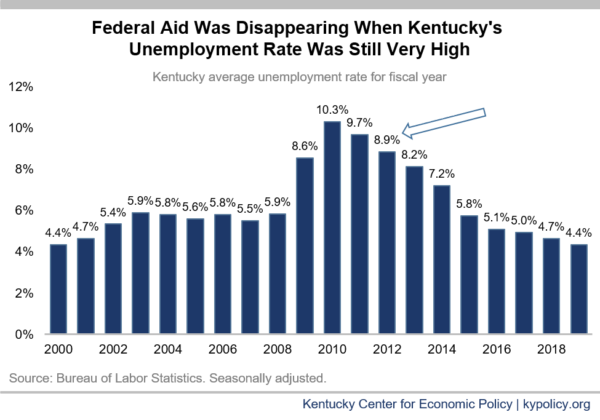

Those added cuts were required in large part because the economy was still in poor shape even while federal assistance was going away, and because the state didn’t raise additional revenue beyond the 2009 tobacco and alcohol tax increases. In 2012, when ARRA assistance dropped sharply, Kentucky’s unemployment rate was still at an extraordinarily high 8.9%. When aid went away completely in 2014, the unemployment rate was still very high at 7.2% and the rate for African American workers in Kentucky, who face more structural barriers to economic opportunities, was still over 10%.

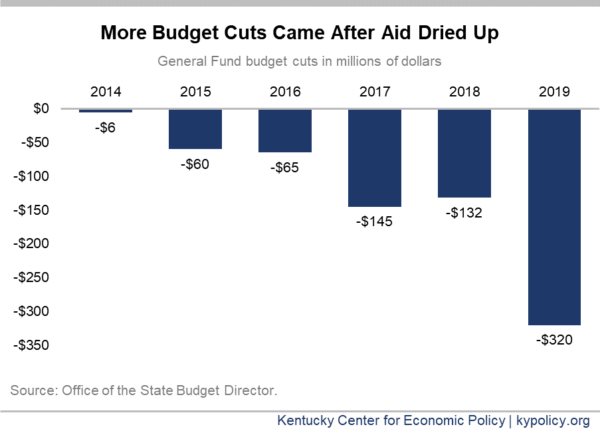

Despite a gradually declining unemployment rate through the remainder of the decade, the state continued to make budget cuts with an additional $728 million in cuts between 2014 and 2019. In part, those cuts came because the economy was still underperforming. The unemployment rate overstated the economy’s strength because some workers dropped out of the labor force due to the extended downturn and were not counted in that rate. Despite the longest economic recovery on record, the share of prime-age Kentucky workers employed in 2019 was still significantly below the nearly full employment economy of the year 2000.

Cuts also continued because one way Kentucky dealt with inadequate funds during the Great Recession was to skip making full contributions to its pension plans. The state resumed making full contributions in 2014 for the state plan and in 2017 for the teachers’ plan, and Kentucky Retirement Systems lowered economic assumptions for its plans due in part to a shrinking state payroll created by budget cuts. The result was much higher pension payments that caused additional cuts elsewhere in the budget.

COVID-19 state fiscal relief so far is inadequate

There are three big lessons to learn from the Great Recession that apply to the fiscal fallout created by the COVID-19 crisis: federal aid to states works, it should be robust and it should last until there is a full recovery.

Without adequate federal aid, state budget cuts drag the economy down further through service reductions and public employee layoffs. In the context of COVID-19, these cuts can also hinder the direct response to the virus through Medicaid, public health, mental health, first responders and more.

In this crisis, Congress has provided some assistance to states. It increased the federal share of Medicaid costs by 6.2 percentage points — a helpful increase, but lower than the 10 percentage points provided during the Great Recession.[6] And instead of providing this assistance through the duration of the economic downturn, it only applies for as long as the federally declared public health emergency is in effect. Congress has also provided Kentucky with $1.599 billion through the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF), $410 million for K-12 schools and higher education institutions, and other targeted monies.[7] However, the CRF funds can only be used for costs directly related to combatting COVID-19 and cannot be used to address revenue shortfalls also caused by the pandemic.[8]

It is increasingly clear this aid is not adequate to deal with the scale of the problem. New research from the Congressional Budget Office projects the U. S. economy will shrink 40% in the current quarter, and Kentucky has already processed an astonishing 500,000 unemployment claims, which equals 24% of the state’s workforce.[9] Having so many people out of work will dramatically reduce state sales, income and other tax receipts. In addition, the state is experiencing an increase in expenses to provide support to Kentuckians who are out of work and need extra help. The Courier-Journal reported that 83,000 additional Kentuckians have already become covered by Medicaid.[10] The CBO also predicts the problem will persist, with a U.S. unemployment rate averaging a stunning 10.1% in calendar year 2021 and a still-painful 9.5% at the end of that year.

The bipartisan National Governors Association and other experts estimated earlier that states need at least $500 billion in relief to mitigate the harm to their budgets and help protect the economy – an amount that is several times larger than the aid Congress has provided so far (the new forecasts suggest the gap is even bigger at $650 billion).[11] There are clear tools the federal government can use to meet this need, including further increasing the match for Medicaid and providing flexible grants.[12] Additional aid should contain triggers so that it continues automatically until the economy has fully recovered rather than being limited to an arbitrary amount or allowed to expire when the public health emergency has ended.

Federal aid to Kentucky was essential in softening the economic blow of the Great Recession. But because the aid wasn’t large enough and didn’t continue long enough given the depth of the downturn, our economy underperformed for the remainder of the decade as the state cut a variety of important services from schools to health to infrastructure. It is critical for Kentucky that Congress not repeat the same mistake again this time around.

[1] Chad Stone, “Fiscal Stimulus Needed to Fight Recessions,” April 16, 2020, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/fiscal-stimulus-needed-to-fight-recessions.

[2] Congressional Budget Office, “Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on Employment and Economic Output from July 2010 to September 2010,” November 2010, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/111th-congress-2009-2010/reports/11-24-arra.pdf. Alan S. Blinder and Mark Zandi, “The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 15, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/the-financial-crisis-lessons-for-the-next-one.

[3] Kaiser Family Foundation, Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier,” https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-matching-rate-and-multiplier/.

[4] Ashley Spalding, “State Budget Cuts to Education Hurt Kentucky’s Classrooms and Kids,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 29, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/state-budget-cuts-education-hurt-kentuckys-classrooms-kids/.Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, “What Does Kentucky Value? A Preview of the 2020-2022 Budget of the Commonwealth,” January 2020, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Final-online-draft.pdf.

[5] House Bill 144, 2019 Regular Session of the Kentucky General Assembly, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/09rs/HB144.html.

[6] Jason Bailey, “Kentucky’s Budget Faces Trouble Without More Federal Aid,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, April 7, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/kentuckys-budget-faces-trouble-without-more-federal-aid/.

[7] Jason Bailey, “What’s In the CARES Act for Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy,” April 3, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/whats-in-the-new-covid-19-relief-bill/.

[8] U. S. Department of Treasury, “Coronavirus Relief Fund Guidance for State, Territorial, Local, and Tribal Governments,” April 22, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Coronavirus-Relief-Fund-Guidance-for-State-Territorial-Local-and-Tribal-Governments.pdf.

[9] Congressional Budget Office, “CBO’s Current Projections of Output, Employment, and Interest Rates and a Preliminary Look at Federal Deficits for 2020 and 2021,” April 24, 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56335. KCEP analysis of Department of Labor and Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

[10] Deborah Yetter, “Kentucky nursing homes ask state to help with soaring costs of masks, gloves amid COVID-19,” Courier Journal, April 22, 2020, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/2020/04/22/coronavirus-kentucky-nursing-homes-seek-help-masks-gloves-cost/2998246001/.

[11] National Governors Association, “Governor’s Request for Third Congressional Supplemental Bill,” March 20, 2020, https://www.nga.org/policy-communications/letters-nga/health-human-services-committee/governors-request-for-third-congressional-supplemental-bill/. Elizabeth McNichol, et al., “States Need Significantly More Fiscal Relief to Slow the Emerging Deep Recession,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 14, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-need-significantly-more-fiscal-relief-to-slow-the-emerging-deep. Celine McNicholas, et al., “The next coronavirus relief package should provide aid to state and local governments, protect employed and unemployed workers, and invest in our democracy,” Economic Policy Institute, April 27, 2020, https://www.epi.org/blog/the-next-coronavirus-relief-package-should-provide-aid-to-state-and-local-governments-protect-employed-and-unemployed-workers-and-invest-in-our-democracy/. Michael Leachman, “New CBO Projections Suggest Even Bigger State Shortfalls,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 29, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/new-cbo-projections-suggest-even-bigger-state-shortfalls.

[12] Matt Broaddus, “Families First’s Medicaid Funding Boost a Useful First Step, But Far From Enough,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 21, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/families-firsts-medicaid-funding-boost-a-useful-first-step-but-far-from-enough.