Since the creation of unemployment insurance in 1938, Kentuckians have been able rely on up to 26 weeks of benefits, giving them the time and flexibility to find a job matching their skills and previous pay. That changes next year.

House Bill 4 (HB 4), passed during the 2022 General Assembly, established a new method for setting the maximum number of weeks a laid-off Kentuckian can claim benefits. Because of new data released today, we know exactly how steep the initial cut will be.

Starting in January, Kentuckians will only receive a maximum of 12 weeks of unemployment benefits, a cut of 14 weeks, or 54%, from where it’s been for 84 years. That will remain in effect until at least July, regardless of how high unemployment jumps. In addition, an extremely stingy change to what kind of jobs unemployment insurance claimants must take in HB 4 can for some reduce benefits to as few as 6 weeks.

These changes are going into effect at the same time economic forecasts are warning of higher unemployment and potentially even a painful recession next year.

Weeks of benefits are based on state unemployment rate from months earlier

All but 10 states in the country provide 26 weeks of unemployment insurance for claimants who are laid off through no fault of their own and have a substantial and recent work history. But HB 4 has added Kentucky to the small list of states that provide less, cutting as many as 14 weeks from the maximum number available. In order to determine how many weeks to cut, the state will “index,” or reduce them, according to the statewide, seasonally adjusted unemployment rate. Specifically:

- The average unemployment rate from July-September will be applied for the duration of benefits for claims filed the following January-June.

- The average unemployment rate from January-March will be applied for the duration of benefits for claims filed the following July-December.

If the three-month average unemployment rate is under 4.5%, claimants only get a maximum of 12 weeks of benefits. An additional week is added for every half-percent increase in the unemployment rate until it exceeds 10%, in which case unemployment claimants only get 24 weeks (still 2 weeks below the historic standard of 26).

The unemployment rate for September 2022 was just published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, meaning now, with an average unemployment rate of 3.8% in July, August and September, claimants will only receive 12 weeks of benefits for the first six months of 2023.

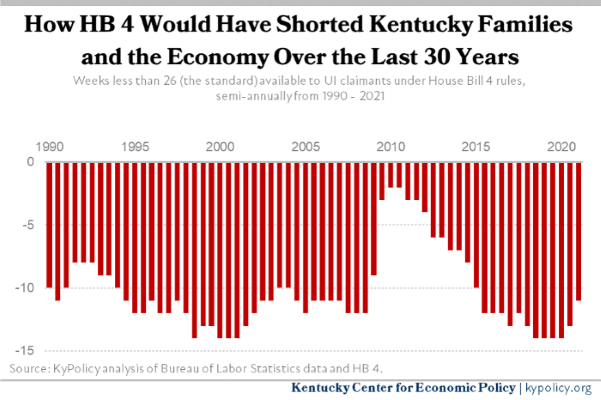

Had this indexing scheme been in place over the past 30 years, there would have only been two, 6-month periods in which claimants would have been able to claim 24 weeks of benefits. During the depth of the 2020 downturn, when unemployment rose above 16% in April, laid-off Kentuckians would have only had 12 weeks of benefits available to them because the number would have been set based on unemployment rates from the third quarter of 2019.

This indexing scheme is based on the statewide unemployment rate, which means that it applies to all counties despite severe differences in unemployment rates across wealthy and poor communities. For example, in 2021 the statewide unemployment rate was 4.7%, but 13 Kentucky counties had an average unemployment rate above 7%, with Magoffin County’s rate reaching 12%. HB 4 will also disproportionately harm Black Kentucky workers, who face higher likelihood of layoffs. While Black workers made up 9.7% of the state workforce in 2021, they comprised 17% of unemployment insurance claims; white workers comprised 86.3% of the workforce, but only 80.1% of unemployment insurance claims.

An extremely stingy “suitability” standard cuts benefits even deeper

While indexing the maximum duration of benefits makes a dramatic reduction in available weeks of unemployment benefits, another change HB 4 made cuts benefits even deeper. The so-called “suitability” standard defines the kinds of jobs unemployment insurance claimants must accept. Prior to HB 4, the suitability standard gave claimants a chance to find a job that matched their skills and prior pay, and did not place a time limit on the job finding process beyond the 26-week maximum duration. HB 4 severely restricts the standard by defining a job as suitable if it:

- Is offered to a worker who has received 6 weeks of benefits,

- Offers a little over half of what their previous job paid (specifically, 120% or more of the weekly benefit amount),

- Is located within 30 miles of their home,

- “Regardless of whether or not he or she has related experience or training.”

This change means, for example, that a factory worker laid off from their $25-an-hour job due to a plant closing would lose their unemployment benefits after just 6 weeks if they were offered a job that paid just $13.50 an hour. That’s an effective 77% cut from the standard 26 weeks of benefits, and a recipe for increased hardship for workers already facing difficult times.

The General Assembly made a mistake passing HB 4 – workers and the economy will pay the price

Unemployment benefits help workers and their families in a time of crisis, and also help blunt the broader harms of an economic downturn. By providing some degree of income replacement, households can continue to meet basic needs, purchasing goods and services in their local economies. This keeps money flowing through communities, protecting businesses and slowing layoffs.

Research has shown that unemployment benefits did just that during the Great Recession, reducing the fall in GDP by two-fifths, with extended benefits contributing to half of that reduction. During downturns, unemployment benefits generate roughly $1.90 in local economies for every $1 claimed. Additionally, more generous unemployment benefits can help speed up recoveries by leading to higher wages and more stable housing markets, without affecting how rigorously claimants look for a job. Even the $600-per-week benefits during the COVID-19 downturn had only a modest effect on job search and acceptance among claimants. On the contrary, claimants who run out of benefits are more likely to drop out of the labor force entirely, and report poor health and increased use of safety net programs like food assistance.

The cuts in unemployment insurance under HB 4 come at a particularly bad time. In an attempt to reduce inflation, the Federal Reserve is unfortunately raising its key interest rate aggressively. This action is designed to reduce economic activity — meaning increased layoffs — and it could well push the economy into a recession in the coming months, as a growing number of experts predict.

But no matter how much unemployment goes up in the first half of 2023, the maximum duration of benefits will remain at 12 weeks, and with very few exceptions it cannot return to the 26 weeks that were available for the first 84 years of the unemployment system. HB 4 will leave us wholly unprepared to handle the fallout of rising job loss by depriving Kentucky families and communities of the anti-recessionary effects of unemployment insurance. It will take action by the General Assembly to undo the harm of passing HB 4.