Wages for Kentucky workers finally grew last year, suggesting both a tightening labor market and pointing to strong recent growth in manufacturing and health care jobs, among other industries. But one year of good news doesn’t change the fact that the gains from economic growth are not being shared equitably with Kentucky workers.

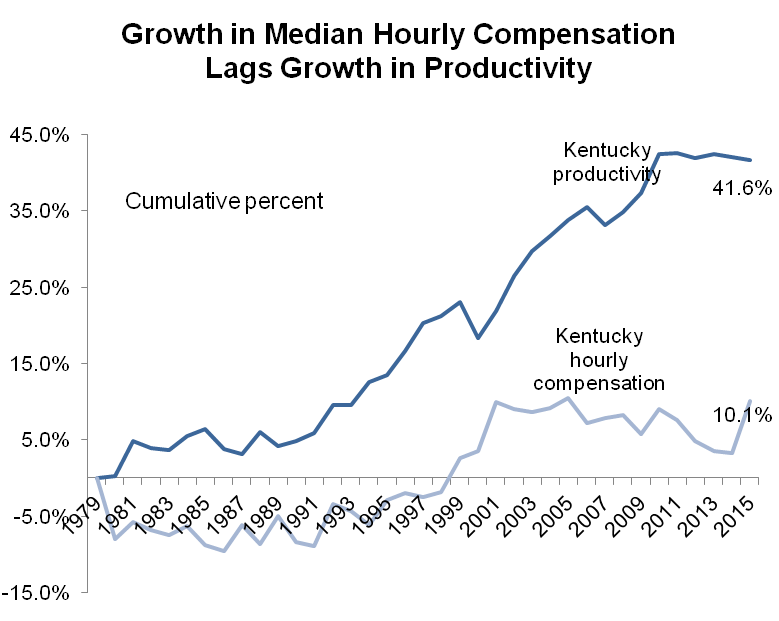

Four decades’ worth of data show a long-term trend in which Kentucky workers’ paychecks are lagging behind growth in productivity, or the value of our economy’s output per hour of work. Between 1979 and 2015, typical Kentucky workers (median production/nonsupervisory workers) saw their real wages grow by 10.1 percent, while productivity grew by more than four times that rate at 41.6 percent.

Source: EPI analysis of unpublished total economy data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and costs program; employment data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics; wage data from the Current Population Survey and compensation data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, State/National Income and Product Accounts public data series.

Ideally, growth in the value of what we produce and what workers make shouldn’t be all that different: besides providing a fair and consistent share of economy-wide gains to the people whose labor helps grow the economy, pay rising in tandem with productivity supports a higher quality of life for a growing middle class. A larger middle class, in turn, generates more consumer demand. In other words, compensation growing in line with productivity is good for workers, their families and the economy.

(The opposite is true as well: when workers’ paychecks shrink relative to the wealth they’re helping create and the middle class contracts, families’ quality of life goes down and the economy suffers from lagging demand.)

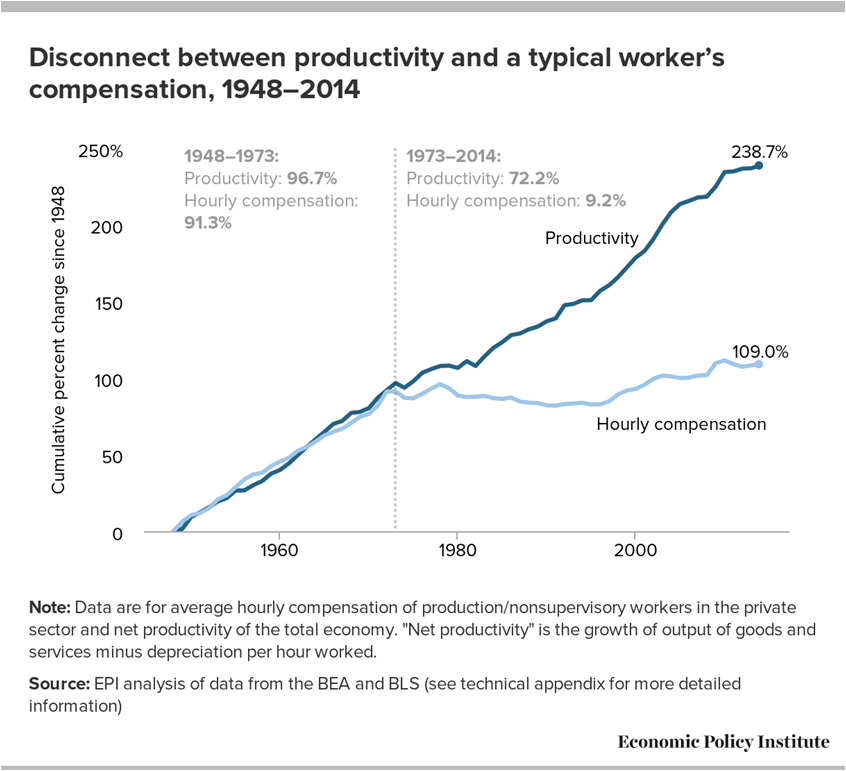

It’s been decades since a virtuous relationship between productivity and compensation gave more Americans a fairer shot at climbing the economic ladder. Since the relationship broke in the early 1970’s nationally, compensation has grown by just 9.2 percent while productivity has gone up by 72.2 percent.

So where is the growth going that once went into typical workers’ paychecks? A rising share goes to owners and shareholders. Furthermore, there is an increasingly unequal distribution for workers across the wage and salary scale, meaning a few at the top are getting a lot more, and everyone else is being left behind. Income data, which capture not just wages and salaries but investment income as well, show that between 1979 and 2013 the top one percent in Kentucky saw their real income grow by 60.1 percent, while for everyone else it dropped 2.6 percent.

Growing inequality of wages and income is not coincidental. Policy action and inaction has decoupled compensation for average workers from productivity through a number of channels: declining unionization; eroding minimum wage and overtime protections (the latter of which will be updated in December); failure to provide workers paid sick and family leave; failure to end discriminatory and abusive employment practices; trade policies that eliminate middle class jobs while benefiting Wall Street interests and the abandonment of policies pursuing full employment, for instance. As the national conversation continues to shift toward building an economy that works for everyone, it will be important that state and federal lawmakers keep these policy issues in mind.