Kentucky’s labor force is a frequent topic of discussion among lawmakers. Too often, those deliberations result in punitive policy proposals because they fail to account for the reality many Kentuckians face both in and outside the labor force. A closer look at the data, however, shows that overall labor force participation trends are driven by large-scale factors like an aging baby boomer population, an Appalachian region with significant and longstanding economic challenges, and high rates of disability and illness. These three drivers largely explain the state’s comparatively low labor force participation. When looking at prime-age workers and non-Appalachian Kentucky, the commonwealth’s labor force looks like the rest of the country’s and continues to trend in a positive direction.

There are opportunities, however, to bring some Kentuckians who are not working, but would like to be, into the labor force. Providing supports like child care, elder care, vocational rehab, and health care as well as investing in job-creating public investment, particularly in eastern Kentucky, could empower more Kentuckians to enter into employment they otherwise would be unable to.

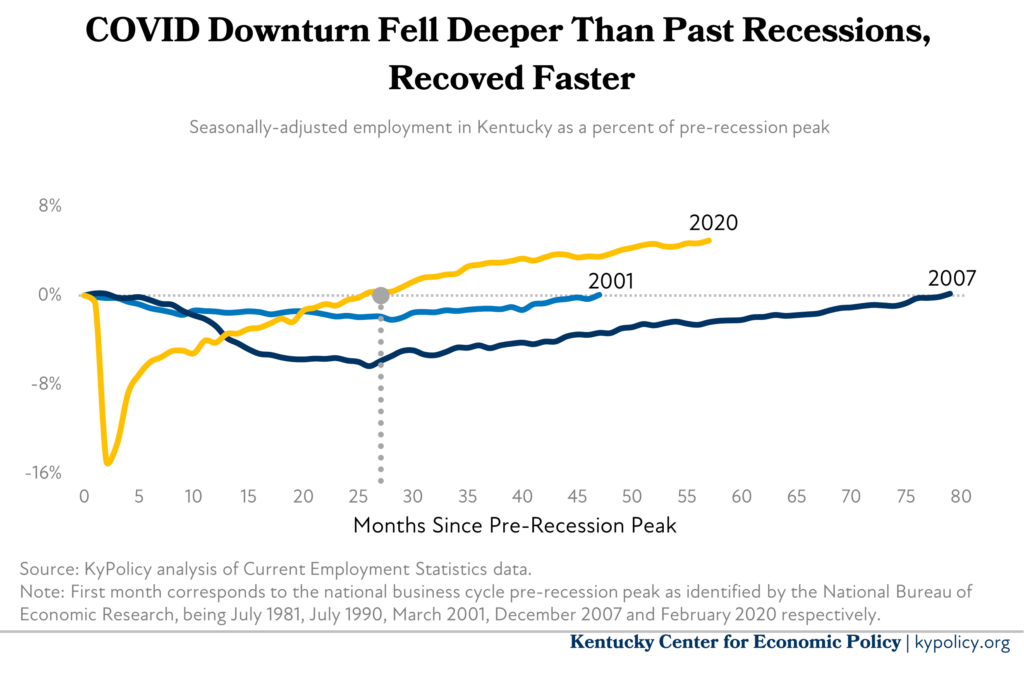

Kentucky’s labor market has steadily and rapidly recovered post-COVID

The recession triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 resulted in job losses three times greater than those during the Great Recession in 2007. And yet, it took just 27 months to return to pre-pandemic levels of employment. As of December 2024, employment in Kentucky sits at 5% above February 2020. This rapid recovery was spurred by multiple rounds of federal relief funding, and has continued in part because of massive federal investments in infrastructure, energy and manufacturing, though the future of those investments is now at risk due to possible cuts by the Trump administration and the new Congress. Far from sitting out, Kentuckians have returned to work post-COVID at a record rate.

There are other indicators of Kentuckians’ motivation to be on the job. Data shows a recent increase in the number of Kentuckians who are actively looking for a job but not currently employed, suggesting that Kentuckians are eager to work. In December 2023, there were just under 86,700 of these Kentuckians and by December 2024 it had increased to over 108,600. In fact, Kentucky’s December unemployment rate (5.2%) was the third highest among states.

Additionally, Kentucky’s labor force participation rate rose throughout 2024, from 56.9% in January to 58.2% by December. Finally, Kentucky workers tend to work more hours than those in most other states. Kentuckians clocked in for an average of 35.1 hours per week in 2023, the seventh longest average work week among states, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Clearly, there has been a sharp increase in the number of Kentuckians gaining employment as more jobs have become available in recent years, and this consistent desire to be employed is important to point out as the backdrop to any discussion about who is not in the labor force.

The real reasons Kentuckians are out of the workforce

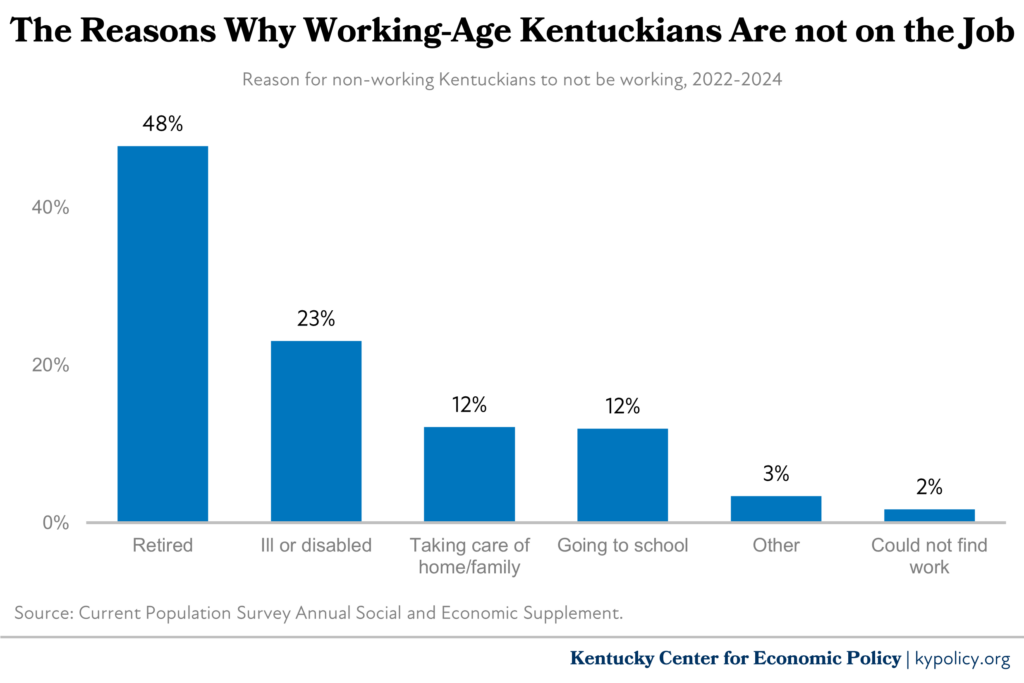

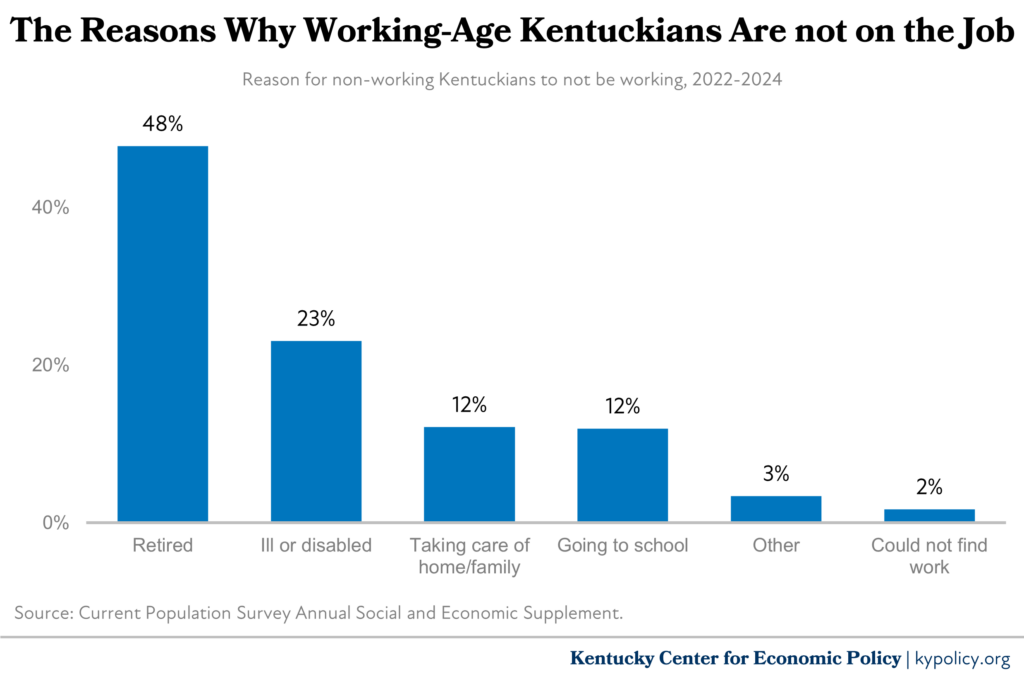

Regarding those who are outside of the labor force, there were 1.4 million Kentuckians age 16 and older not currently working at some point between 2022 and 2024 according to the Current Population Survey (CPS), 95% fall into one of four categories:

- They are retired.

- They are ill or disabled.

- They are taking care of their home or a family member.

- They are going to school.

The remaining 5% are either currently looking for a job or they are not working for some other reason that the survey could not identify.

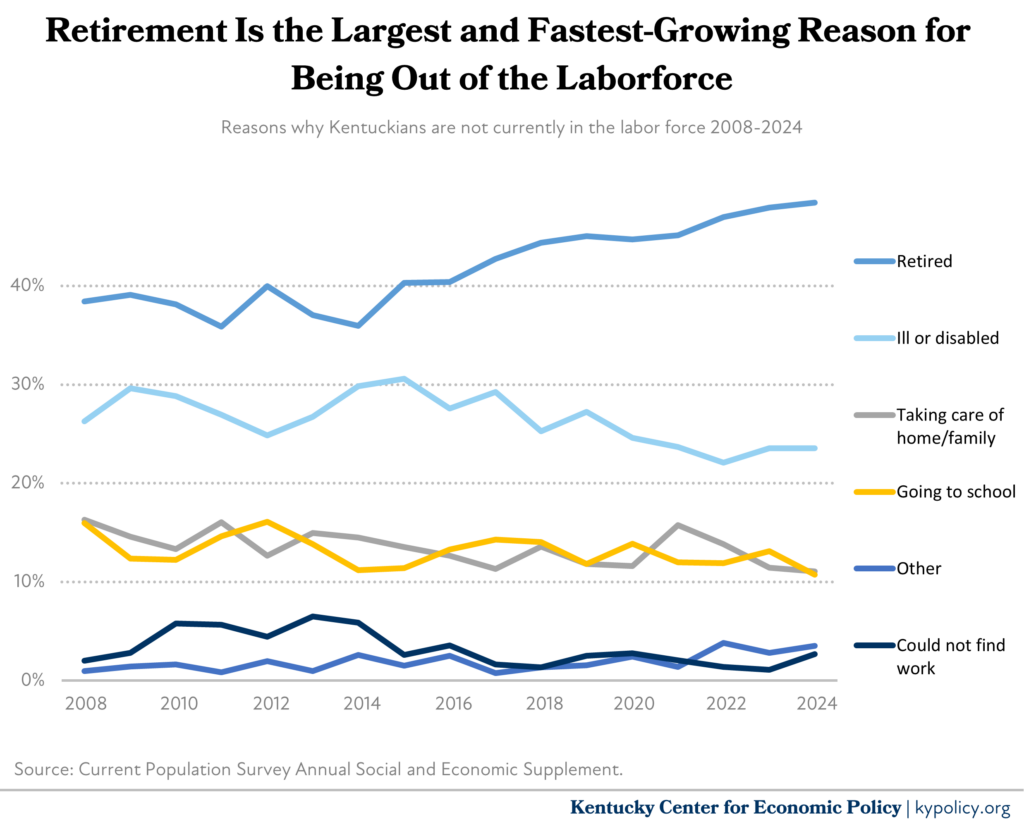

Like the rest of the country, Kentucky is currently undergoing a significant demographic shift as the Baby Boomer generation ages into retirement. In 2008, Kentuckians age 65 and older comprised 13% of the state population; by 2023 they were 18%. In turn, the share of working-age Kentuckians (ages 16 and older) who are not working because they are retired grew from 38% in 2008 to 48% by 2024. All other reasons for not working were either stable or decreased over those years.

Although fewer Kentuckians have been out of work due to an illness or disability in recent years, it remains another major reason for Kentuckians to abstain from the labor force. Kentucky’s relatively poor health is a factor here, with the highest incidence rate of cancer in the country, the second highest rate of cancer deaths, the seventh highest rate of drug overdose deaths, and the eighth highest rate of heart disease related death.

Kentucky also has the second highest percentage of its residents with a disability at 18.1%, far higher than the national average of 13.6%, as of 2023. The most common types of disabilities in Kentucky are related to cognition (17%) and mobility (16%), but include difficulties with independent living, hearing, vision and self care. There are opportunities to assist Kentuckians with disabilities to enter the workforce, and jobs available to workers requiring accommodations are growing. However, many will not be able to enter the labor market due to the severity of their disability. Kentucky has an unusually high share of workers who are employed in physically demanding jobs that include risk for injury and disability – ranking seventh among sates for the share of our employment that is mining or logging, manufacturing and construction (17.5%).

Most of these Kentuckians don’t receive any financial assistance due to their disability, either. Kentucky’s approval rate at application for Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is only 33.4%, and only an additional 9.8% are approved upon reconsideration. For the minority of disabled applicants who do have claims approved, the benefits are small – $1,580 per month for SSDI, and just $678 per month for SSI.

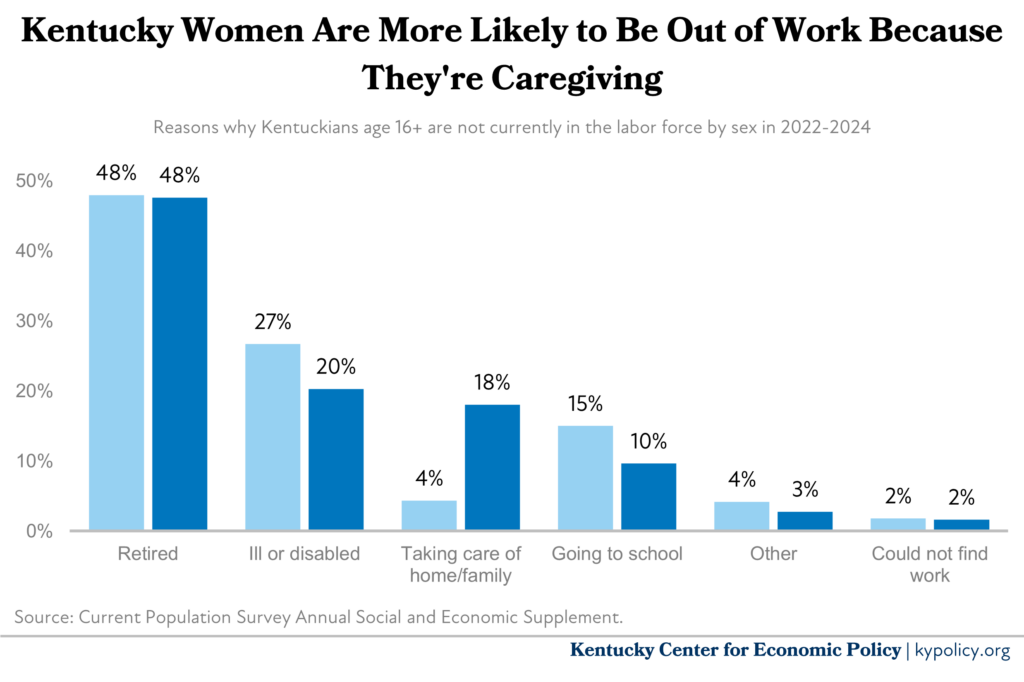

In breaking out reasons for not working by sex, Kentucky men and women are both retired at the same rate of 48% between 2022 and 2024. However, men were more likely to be out of the workforce because they were ill or disabled (27%) or because they were in school (15%) than women (20% and 10% respectively). Women, on the other hand, were more than four times more likely to be at home caring for a loved one like a child or aging parent (18%) than men (4%).

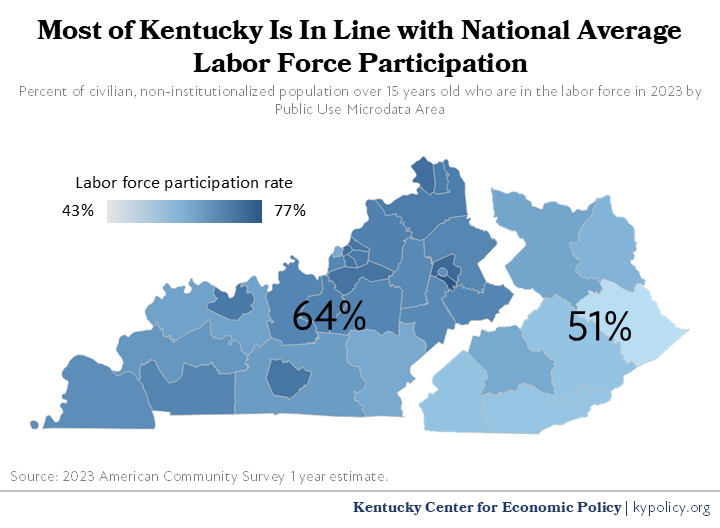

Eastern Kentucky’s longstanding economic headwinds have a significant impact on the state’s average labor force participation rate. It remains a region deeply harmed by decades of deindustrialization and lack the public investment. Many people have migrated out of eastern Kentucky over the decades due to the lack of job opportunities, but rising housing prices and historically stagnant wages for working class jobs in some urban areas make such moves less attractive than in certain periods in the past. Individuals who migrate often must leave family support networks, land and other resources they now count on. Hyperbolic and stereotypical claims about Kentuckians in general and eastern Kentuckians in particular lacking interest in work are not based in fact. Eastern Kentuckians have long been employed in among the most demanding and dangerous jobs such as logging and mining. But the region and certain other communities in Kentucky struggle from a scarcity of job opportunities that requires more public action to address. The result is that the American Community Survey (ACS) estimates a labor force participation rate (51%) so much lower than the rest of the state that without it, the remainder of Kentucky has a labor force participation rate (64%) identical to the national average.

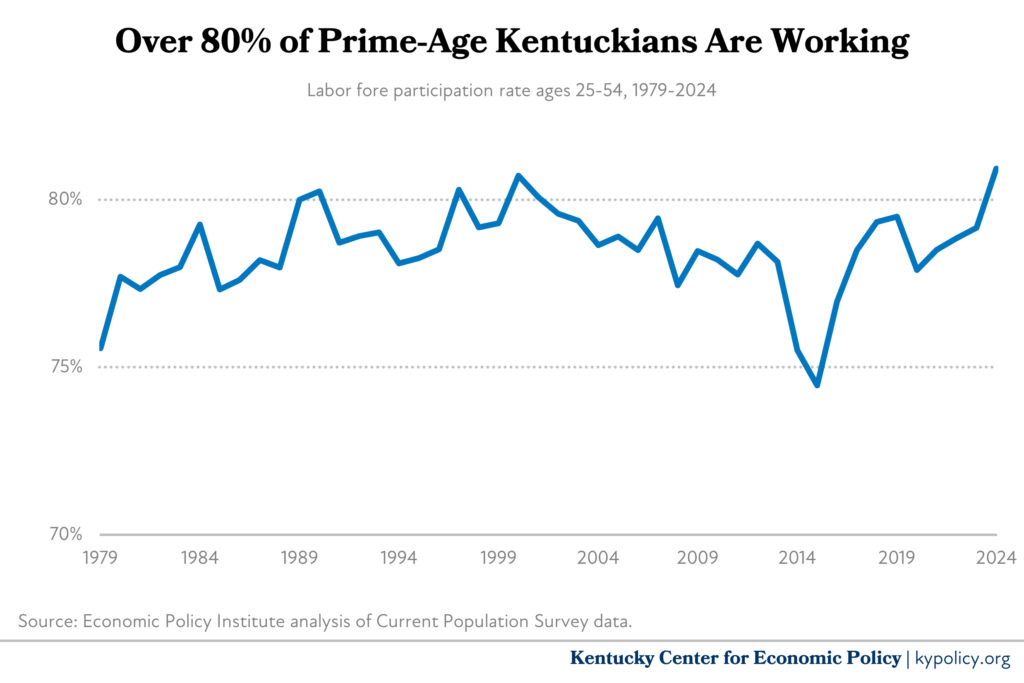

Kentucky’s prime-age workers mirror the national average

While much attention is given to the overall labor force participation rate, a better indicator of workforce participation is the share of the working age population ages 25 to 54 who are in the labor force, a group known as the “prime-age” workforce. Rather than declining, that share is growing as more jobs are created in the post-pandemic economic recovery described above. The prime age rate was 80.9% in 2024, an increase from 77.9% in 2020. That is the highest prime age labor force participation rate in at least the past half century.

Of the approximately 20% of prime-age workers not in the labor force during 2022-2024, three-fourths were either caregivers, or ill or disabled as shown below. Only 6% are categorized as “other” because their reason for not working could not be determined. In addition, it is important to note that labor force participation rates are snapshots in time (specifically in March of each year for the survey this data came from); they do not mean that the same people remain in the same categories, or even out of work all year. Especially at the bottom of the labor market, conditions often change as individuals face greater instability related to housing, transportation, health, family relations, employment and other issues.

Public assistance is a work support

Hundreds of thousands of Kentucky workers earn so little that they qualify for public assistance like the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP), the Kentucky Transitional Assistance Program (K-TAP, or basic cash assistance), Medicaid, or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or food assistance). These programs are designed to help Kentuckians with low earnings get to a doctor, use child care, and afford necessities like groceries or diapers. Additionally, each of these programs is designed to support participants in their jobs.

For example, in CCAP, KTAP and SNAP, the amount of assistance phases out gradually as participants earn more, preventing their overall economic condition from worsening as their incomes rise. For KTAP and SNAP, there are additional supports available to working participants such as SNAP Employment and Training (E&T) opportunities and the Kentucky Works Program in KTAP, which offers a wide range of financial supports like transportation assistance, car repair funds, tuition for credentials, relocation assistance, and money for materials required for a job like tools or uniforms. Medicaid also helps participants’ employability by providing a comprehensive suite of health services including life-saving cancer screenings, chronic condition management and eyeglasses, for example.

Additionally, there have been false claims that high usage of public assistance among working-age Kentuckians is disincentivizing work, particularly SNAP, which some use to justify proposals to restrict eligibility. That claim is contradicted by the fact that many people who are eligible do not use the program – if food assistance usage was impeding work participation, you would expect participation to be closer to 100%. Instead, Kentucky’s participation rate is the 4th lowest in the nation with only 65% of eligible Kentuckians participating in the program. In 2020 (the most recent such data available), this meant that nearly 380,000 Kentuckians could be using SNAP but were not. That is both a higher non-participation percentage, and a larger population of non-participants, than all of our surrounding states.

It is also worth noting that the $18 billion Kentucky spends on Medicaid ($4 in $5 of which is federally funded) supports hundreds of thousands of jobs throughout the commonwealth. Nearly every aspect of the health care and social assistance sector is financially supported in some way through Medicaid, and it employed 291,200 Kentuckians as of December 2024. Medicaid spending, like all health care spending, also ripples throughout local economies. In terms of jobs, for every 100 jobs in the health care and social assistance sector, an estimated 205 additional jobs are created or supported in other sectors. Far from limiting participation in employment, Medicaid helps make more employment available.

Kentucky’s labor force is strong, but targeted supports can help

The rebounded labor force following COVID-19 was remarkable in its breadth, speed and consistency. In many ways, we should celebrate the federal efforts that led to such a successful economic recovery in the commonwealth, and do what we can to keep that momentum, including maintaining or improving state investments in education, health care and infrastructure.

According to the Current Population Survey, in addition to the 108,600 Kentuckians actively seeking work in December 2024 (who are technically included in the total labor force), there were 80,000 more Kentuckians who were outside of the labor force but would like to have a regular job between 2022 and 2024. This means there are Kentuckians who could be supported to join the labor force. Knowing why non-working Kentuckians are not in the workforce points us to policy options for helpful work supports. For example, on average between 2022 and 2024, 14,800 were out of the workforce but wanted a regular job because they were caring for a loved one. Improved child care options and affordability, or increased opportunities for home and community-based services, might provide an opportunity for some to enter the workforce. During that same period, an average of 10,300 were out of the workforce due to an illness or disability but wanted a regular job. For these Kentuckians, increased access to health treatment and improved vocational rehabilitation or supported employment programs could provide a pathway toward a job.

Additionally, when discussing Kentucky’s labor force participation rate, it is important to make the distinction between eastern Kentucky and the rest of the state. When lawmakers are talking about “sidelined” workers that lead to labor force participation rates below the national average, they are primarily referring to eastern Kentucky whether they know it or not. But as discussed, the lack of jobs in this region means it needs more investment and support, rather than threats of losing public assistance. Recent federal industrial policies like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law or the Inflation Reduction Act provide real and significant opportunities for such investments, and state administrators could help direct resources to projects in that region, with community benefit agreements to ensure the new resources spur local growth.

Another potential entry point for workers outside the labor force is apprenticeships in various trades. Between 2011 and 2023, annual apprentices have risen 326% in Kentucky, with over 3,000 apprentices in training by 2023. These opportunities were mainly in construction but included other sectors like utilities and manufacturing. Apprenticeships are an important pathway for young people who want to enter the workforce debt-free while bypassing a college education, the cost of which grew consistently through 2018 in Kentucky, and remains higher than the national average.

Many of the federally-funded work supports mentioned above – Medicaid, SNAP, KTAP, industrial policies, child care, etc. – are now at risk under the President’s and congressional leadership’s current priorities. Planned cuts to these and other programs to pay for an extension of the 2017 tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations would have a devastating impact on Kentuckians’ ability to gain and maintain stable employment, in addition to their health and wellbeing. In other words, deep cuts to federal spending would mean a setback for Kentucky workers rather than a way to remove barriers that they face.