Kentucky’s past experience with Association Health Plans (AHPs) has gained new relevance amid a court battle over the legality of a U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) rule that relaxed standards for AHPs in an effort to make them more widely available. The history of these plans in Kentucky shows how expanding plans subject to weaker rules undermines the health insurance protections in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and is likely to harm those who are more likely to need care.

DOL rule expanded availability of AHPs

AHPs are health plans that trade groups and professional organizations offer to their members. After enactment of the ACA, which made a number of changes to commercial insurance rules, 2011 guidance clarified that plans sold to individuals and small businesses (including through associations) generally must meet the ACA reforms that apply to those markets. Then, the DOL issued a rule in 2018 that sought to restart the AHP market by making AHPs easier to form and to be considered large-group health plans, rather than having to meet the ACA’s standards for the individual and small-group markets – even when AHP enrollees are self-employed individuals or small businesses.

In this way, the rule enabled AHPs to bypass standards that would otherwise apply, including by not covering all essential health benefits, charging higher premiums based on age than is allowed under the ACA, considering factors such as gender and occupation in setting premiums, and pricing plans in a separate risk pool. Some AHPs that are available to small businesses, but not individuals, also can consider health status when setting premiums.

In addition, some individuals and small businesses that are healthier than average may be able to pay a lower premium for an AHP – but only at the expense of higher costs for sicker-than-average firms and workers who remain in the traditional small-group and individual markets. AHPs may also provide weaker cost and coverage protections. While healthier people can generally afford to take the greater risks associated with these lower-cost, lower-coverage health plans, the differences in premium costs and benefit standards allow association plans to siphon off healthy participants from the individual and small-group markets, leaving behind a smaller, sicker and therefore more expensive pool in their wake.

This isn’t the first time AHPs have hurt health protections in Kentucky

In the mid-90s, Kentucky implemented a suite of health insurance reforms that were meant to protect Kentuckians with pre-existing conditions, provide affordable health insurance to individuals and lower costs for some employer health plans. But according to an analysis from 2000, AHPs were one factor that doomed those reforms by keeping healthy people out of the individual market – a problem known as adverse selection.

Specifically, the individual market reforms included many features that were later passed federally with the Affordable Care Act (ACA):

- A standardized set of benefits that all plans had to include in insurance policies.

- Guaranteed issue and renewal, meaning insurance companies had to insure people who applied for coverage with them and renew those policies.

- Modified community rating that prohibited insurance companies from basing premiums on health status, gender or the medical claims history of an applicant.

- Premiums that could be based on age, family composition and geography, though the highest premium for a given insurance plan could not be more than three times more than the lowest premium.

However, in Kentucky, association plans were exempted from these reforms. Insurers took advantage of the less-regulated association market rather than comply with the higher standards the state implemented in the individual market.

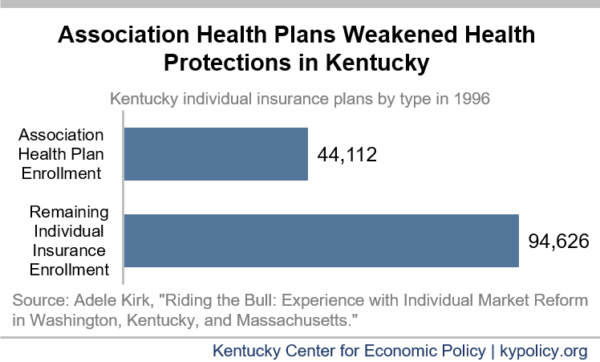

By 1996, a third of the 138,738 Kentuckians who directly purchased insurance (rather than getting it through an employer or Medicare/Medicaid) were part of an AHP. The study estimated that because AHPs were exempted from the reforms, and many pre-reform plans could be renewed, less than half of the insurance market ever saw any of the protections under the health reform go into place. This market segmentation was enough to dissuade insurers from participating in the individual market. Anthem was so averse to the individual market, for example, that it paid insurance agents a full commission for association products, but dropped its individual market commission to only $5 for each policy they sold. By the end of 1996, only two insurance companies still sold individual plans. The Kentucky reforms failed and the General Assembly repealed them soon thereafter.

DOL rule undermines health protections nationally

After the ACA and the 2011 guidance, research suggests that many AHPs disbanded. But the 2018 DOL rule further broadens the availability of AHPs by relaxing its standards for who can be covered by them, which is likely to lead more healthy people to leave the ACA-compliant markets.

Furthermore, though the rule still prohibits one type of AHP from basing premiums on many health-related factors, it allows them to discriminate based on factors such as the gender and industry of the applicants that correlate closely with health status. And while age can be a consideration for both the ACA marketplace plans and AHPs, AHPs can charge older workers and firms that skew older much more than the ACA allows (as was also the case in Kentucky). These kinds of plans are also not required to provide the ACA-mandated “essential health benefits” which newly required coverage for things like mental health care, maternity care and prescription drugs.

Nationally, the ACA’s subsidies for low-income individuals purchasing a plan on the marketplace protect it somewhat from a broader availability of AHPs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that 200,000 people who purchase individual coverage there would move to an AHP over 10 years if the DOL rule remains in place. However, the CBO estimates that 3.1 million people would move from small-group health plans (employer sponsored insurance for businesses with 100 employees or fewer) sold on the marketplace to an AHP under the rule. This shift would be a substantial reduction of participation in the ACA-compliant small group market.

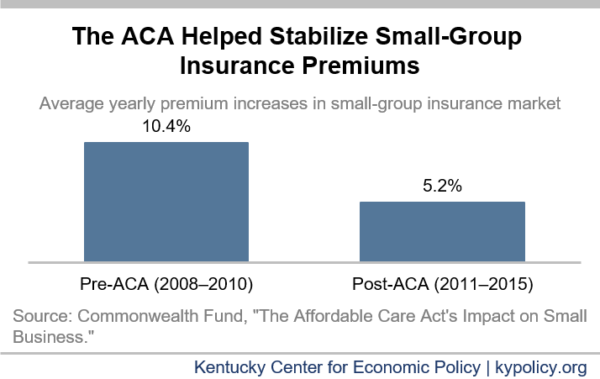

Small-group health insurance was greatly improved by the ACA. From 2008-2010, the years immediately preceding the ACA, small-group plan premiums were rising an average 10.4% per year; but from 2011-2015 premium growth was cut in half to 5.2% per year.

Not only did premium growth fall, but the uninsured rate for small business employees fell by almost 10 percentage points. The ACA was not the only factor in this decline in the rate of uninsured among workers in small businesses, but it was an important factor. Because the protections for people enrolled in AHPs are weaker, they can attract people with even lower health care costs and thereby leave sicker, more expensive enrollees on the small group ACA marketplace – stunting or even reversing these gains realized under the ACA over the past decade.

As the DOL rule makes its way through the courts, Kentucky’s experience with AHPs undermining meaningful health protections should serve as a warning against federal efforts to expand AHPs. The federal judge who initially struck down the DOL rule said it was “clearly an end-run” around the intended health protections in the ACA. This was certainly true about past reforms in Kentucky.