Kentucky’s basic cash assistance program for families with young children was recently overhauled to make long-overdue and badly needed improvements benefitting children and families across the commonwealth. These changes in the Kentucky Transitional Assistance Program (KTAP) included a large increase to the benefit amount, modest increases to eligibility levels, the repeal of outdated penalties for two-parent households, reduced “benefits cliffs” and substantial work supports.

Kentucky has not prioritized updating the program over the past three decades. Consequently, the program’s benefit and income eligibility levels had fallen an inflation-adjusted 46% since the last increase in 1995 , leading to shrinking rolls and less value for those who did participate.

Basic cash assistance has a decades-long track record of benefits for children and their families, including improved health, education and employment outcomes. The recent updates to KTAP reinforce those benefits, and are crucial to the success of children from households with extremely low incomes.

Twenty-seven years of neglect had taken its toll on KTAP benefits and income eligibility

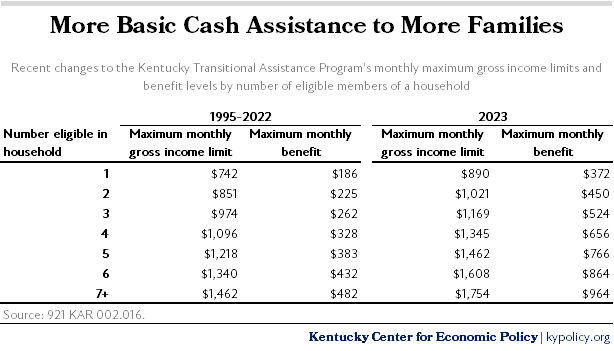

The income eligibility limit for KTAP is not like other public assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Medicaid, which automatically adjust with inflation. Rather, the income eligibility level for KTAP is based on a fixed dollar amount, which is extremely low, that hadn’t changed since 1995. Prior to its increase in March 2023, the maximum monthly benefit level was just $262, and the monthly income eligibility limit was just $974 for a household of three. That meant a mother with two children would not qualify for benefits if they made $12,000 or more a year.

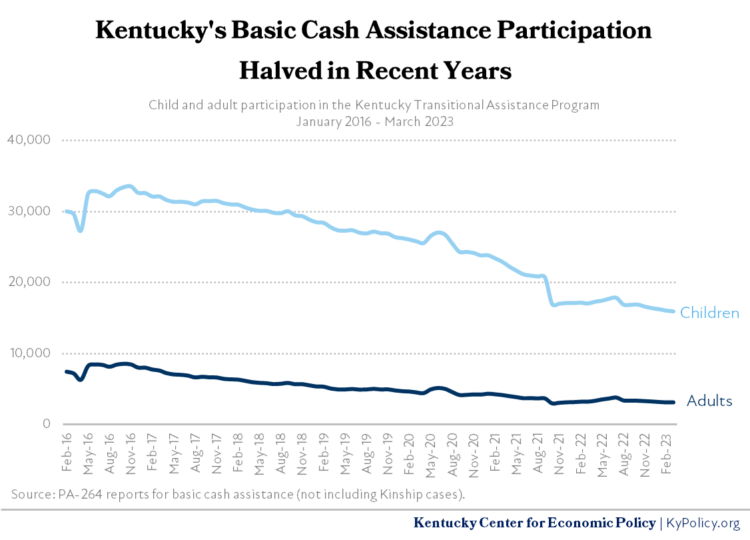

The frozen eligibility level led to a massive drop in participation. In 1995, over 72,000 families were receiving basic cash assistance through KTAP. By 2022, Kentucky averaged 10,000 families per month. Since 2016 alone, the total number of Kentuckians receiving KTAP has fallen 54%, and by the end of 2022 only 3,174 adults and 16,595 children were participating (compared to over half a million in SNAP and 1.7 million in Medicaid).

Inflation has risen 92% between 1995 and 2023. The maximum benefit level for a household of three would have been $503 last year (vs. the $262 it actually was) had it just kept up with inflation. The updated regulations for KTAP double the benefit level (to $524 for a household of three, for example) – just above the inflation-adjusted equivalent for 1995. Had income eligibility levels kept up with inflation since 1995, it would have allowed a family of three making $1,870-per-month to participate. The recent updates increased the income limit for a household of three from $974-per-month to $1,169-per-month. That is equivalent to just 54% of the Federal Poverty Level, which, though a marked improvement, still remains far below the level for SNAP (100%) or Medicaid (138%).

Prior to the recent improvements, Kentucky’s benefit amount was the fourth lowest in the nation and half the value of the median state’s benefit. We were one of just 16 states that had not updated its benefit since Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) was created, which is the funding source for state basic cash assistance programs, became law. In the past two years alone, 23 states increased their benefit amounts, including five of our surrounding states (IL, OH, TN, VA and WV) and seven states in the south (LA, MS, SC, TN, TX, VA and WV).

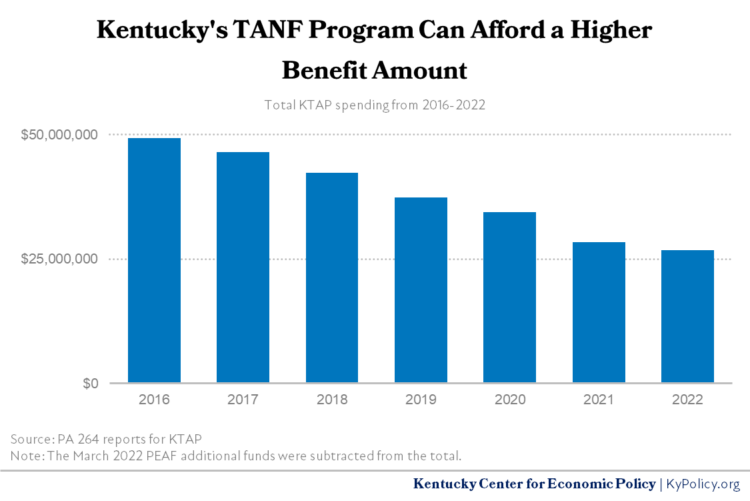

There was enough money in Kentucky’s TANF block grant for an update

Because participation has fallen so much and benefits were frozen for so long, total KTAP spending has fallen 46% in the past six years alone. That means Kentucky is spending $22.6 million less than it did in 2016 on KTAP benefits, and far less than 1995. Kentucky’s TANF block grant is approximately $180 million. It has not increased since it was implemented and will not increase without an act of Congress.

Other regulation updates bring KTAP out of the LBJ-era of welfare

Many other decades-old policies were changed with the recent KTAP regulation improvements. These focused on reducing barriers to participation, reducing the cliff effect of earning income while participating, offering alternatives to KTAP and providing work supports. In all, they represent a far better designed basic cash assistance program for participants who use it and the state agency that administers it.

Asset limit raised from $2,000 to $10,000. To be eligible to participate, households must meet both an income eligibility limit, and hold assets below a certain value. Those assets could include cash in a bank account, savings, some types of retirement accounts, the value of a second family car, family farm land or even the value of outstanding student loans. The new regulations for KTAP increase that limit from $2,000 to $10,000. This also allows families to save for the future while participating in the program.

Ended the two-parent penalty known as “deprivation factors.” Going back to the precursor to TANF known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children, signed into law by President Johnson, only single mothers or households where the traditional breadwinner was unable to work could qualify for basic cash assistance. This was based on the assumption that is no longer a reality – that fathers would work and mothers stay at home. This created a penalty for low-wage-earning, two-parent households that need assistance. As pay and benefits have deteriorated over time, it is now commonplace that both parents in a two-parent family must work for low-wage families to get by. The new rules eliminate the so-called “deprivation factors,” and allows more two-parent families to receive KTAP.

Reduces the penalty for increasing wages. The benefit amount for KTAP-participants is reduced as households earn more, but this can penalize households when their earnings get too high for benefits, but not high enough to live on. To address this problem, the new KTAP regulations create a two-staged income disregard. For the first six months after a household is determined eligible, all increased earnings (either from a current employer or from a new job) are disregarded for benefit levels or eligibility. For the second six months, 50% of earnings are disregarded. After the first year, the proration of benefits continues like normal.

Smooths out the post-eligibility drop-off in assistance for working households. Previously, a household that was no longer eligible, either because their income became too high or because they reached the 60-month lifetime limit, could receive $130-per-month for up to nine months as long as the former adult participant was continuously working. Now, they can receive a Work Incentive benefit of $200-per–month for up to 12 payments after eligibility ends, as long as they are employed. However, those months no longer have to be consecutive, so someone could receive the post-eligibility benefit again after a gap in employment. The new regulations also disregard the first $175 of income when determining eligibility – up from $90.

Increases the one-off benefit of the KTAP alternative known as “FAST.” For some applicants who are eligible for KTAP, a larger, one-time benefit may be more useful than smaller, continued payments. For those folks, the Family Assistance Short Term (FAST) benefit can be used to repair a car, pay for unsubsidized child care, cover utilities, make a housing payment or purchase some items used for employment. The new regulations doubled the FAST benefit from a maximum of $1,300 to a maximum of $2,600.

Provides numerous improvements to various work supports. There are a number of ways in which KTAP provides support to participants who need support in their jobs. The updates to KTAP improved on each of them:

- Increases car repair assistance from $1,500 to $3,000 per household over a 12 month period.

- Increases transportation assistance from a maximum of $200 per month to $300 per month.

- Increases assistance with required fees needed for a job (such as training, registration fees, testing, applications, etc.) from a maximum of $200-per-fee to $400-per-fee.

- Expands the current Relocation Assistance Program (RAP) to help participants who have to move for work from $500 to $1,500.

- Improves assistance for other work related expenses such as uniforms, interview outfits or tools from $400 to $600 per 12-month-period.

Ideally, these supports should help set participants up for more stable, better-paying work than is typical for TANF basic cash assistance participants who exhaust their eligibility. Historically, post-eligibility employment has been inconsistent and insufficient – which is why participants needed assistance while raising children to begin with.

Basic cash assistance works to improve the lives of Kentucky kids

Households that participate in KTAP include single parents, unemployed or disabled two-parent homes, and grandparents, all raising children, and all in extremely challenging financial circumstances. Robust research dating back to the 1960s show that basic cash assistance and near-cash assistance (such as the EITC, housing vouchers or SNAP) provide a broad array of benefits immediately and well into adulthood for participating children. Those include:

- Improved performance at school

- Increased rates of college enrollment

- Improved infant health, such as reduced premature births

- Lower rates of heart disease and obesity among adults who received SNAP as children

- Improved behavior among children

- Reduced likelihood of homelessness

- Increased earnings after reaching adulthood

- More working hours each year after reaching adulthood

More recent research that looked at the effect of the 2021 boosted Child Tax Credit showed improved brain development among the first year of children’s lives in homes where families received the benefit. For families who are victims of domestic violence, TANF can make the difference in achieving the financial independence needed to leave an unsafe situation.

The increases to KTAP were long overdue, and in the first month of their implementation, participation jumped by over 500 people (over 300 of whom were children) and benefits were doubled. These improvements should be celebrated, learned from and built upon as policy makers make future decisions related to Kentucky’s economic security programs.